workover rig companies in north dakota pricelist

Assists the Rig Operator in performing job activities associated with the rig-up and rig-down of the workover rig, picking up/laying down and standing back rods…

Manages tools on the workover rig floor and assists in daily maintenance. Must have a minimum of 1 year of experience as a workover rig floorhand to be…

Spot in, rig up, and rig down well service unit (rig). Minimum of 1 year operating rig. Workover rig experience (minimum 6 months verified experience).

Installs / disassembles (rig up/rig down) of wireline and pressure control equipment in accordance with original equipment manufacturer’s standards including…

Operate the rig safely during rig up/down and pulling operations. Perform all required equipment inspections-workover rig, fall arrest system, derrick, hoisting…

The successful candidate will have an outstanding track record of success in workover rig experience in operating heavy equipment while ensuring communication…

Ensures all crew members are at the rig and prepared to work at the scheduled time. Determines how a service job will be performed based on specific conditions…

Inspects the setting up, taking down and transportation of the assigned workover rig. The Rig Operator, reporting to the assigned Tool Pusher/Field Supervisor,…

Operate the rig safely during rig up/down and pulling operations. Perform all required equipment inspections-workover rig, fall arrest system, derrick, hoisting…

Communicates with customer and/or the delegated well site representative, rig crew and field support staff. Plans, directs, supervises, and evaluates the work…

3+ years workover rig / wellsite supervisory experience. Ensures efficient maintenance of assigned rig and equipment. High school diploma, equivalent or higher.

The Floor Hand position is part of a 4-5 person workover rig crew on a well service rig, who are responsible for performing services on oil and gas wells…

Operate the rig safely during rig up/down and pulling operations. Perform all required equipment inspections-workover rig, fall arrest system, derrick, hoisting…

Perform services on oil and gas wells as part of a 3-5 person workover rig crew. Lifts, removes, installs and operates well head pump, jacks and performs other…

We are immediately hiring full snubbing crews for 170k stand alone rig assist and 150k rig assist snubbing units! High school diploma, GED or equivalent.

Every workover rig available is going right now in the Bakken, North Dakota’s top oil and gas regulator Lynn Helms said on Friday, during his monthly oil production report, as companies try to get wells online as quickly as possible after back-to-back blizzards idled a substantial number of four and five-well pads in Williams, Divide, and McKenzie counties.

March was a good month for production, Helms said, with a 2.8 percent increase in crude oil production from 1.089 million barrels per day to 1.12 million barrels per day. That figure is 2 percent above revenue forecast. Gas production, meanwhile, rose 4.5 percent to 3.01 billion cubic feet per day from 2.87 billion cubic feet per day in February.

Gas capture percentages were 95 percent, and this time Fort Berthold was a bright spot, with 97 percent capture. Helms said he expects continued improvement in the Fort Berthold area, with new solutions for gas capture in the works for the Twin Buttes area, which has been a problem spot.

But production is not going to look as rosy in April, Helms said, and may not look great in May either, given the time it will take to repair electrical distribution infrastructure. Load limits remain in place because of wet conditions, and that is a condition that might go on for a while, given the recent flooding issues caused by rain.

“We saw production in the first blizzard dropped from about 1.1 million barrels a day to 750,000 a day,” Helms said. “We recovered not quite back to a million barrels a day. And then the second blizzard came in. It was heavily impactful on electrical power and infrastructure in the Bakken oil fields.”

“It took a week, or I guess within a little bit less than a week, we recovered to 700,000 and it’s taken another week, we think we’re back at about a million barrels a day.”

One of the biggest of problems was that so many natural gas processing plants were knocked out of service, some for nine hours and others for well over a week.

“Just this past week, our largest gas plant came on and that’s really enabled a lot of production to come back on,” Helms said. “So we’re back to a million barrels a day, maybe a little more. You know all of the large operators reported enormous production losses. And of course that has led to the deployment of every workover rig available being out there trying to get wells back on production.”

Last weekend in Williams County, a dozen four and five-well pads along Highway 2, headed toward Ray, remained idle. They appeared to be without electricity, with some poles still clearly broken and lines laying down on the ground.

In his discussions with drilling contractors, Helms has learned that most drilling rigs went south to Texas and New Mexico, both of which escape winter sooner than the Bakken. Those areas hired the available workforce, too, which has added to the Bakken’s difficulty in attracting workforce.

“It’s taking around two months to train and deploy a drilling rig and crew, and very similar timeframes for frack crews,” Helms said. “So it’s just very, very slowly coming back.”

“There have not been any new frack fleets constructed since before the pandemic,” Helms said. “So the iron that’s out there is starting to show some wear and tear, some age, and, at some point, we’re going to have to see capital deployed to bring that iron back on.”

“I was reading an article today, and some of the large operators were saying, ‘Well you know we could bid up the price to hire frack crews, but all we would be doing is hiring them away from smaller companies that can’t afford to pay as much.’ So there wouldn’t be a gain in the number operating, in the number of wells completed, or really a more rapid rise in production. So it’s very much workforce limited.”

North Dakota rig counts are at 40 right now and Montana rigs are at 2, according to figures from North Dakota Pipeline Authority Justin Kringstad. Helms said the Bakken hasn’t seen those numbers since March of 2020. There are about 15 frack crews running now, a number last seen in April 2020.

Prices, however, have been well ahead of revenue forecasts, pushed in part by sanctions against Russia, which attempt to choke a major source of financial capital for the invasion of Ukraine, as well as continued supply chain issues and lower than expected production from OPEC.

“Today’s price is almost $102 a barrel for North Dakota light sweet and $106 West Texas,” Helms said. “So we’re estimating about $104 a barrel for North Dakota crude prices. That’s more than double revenue forecast. Revenue forecast was based on $50 oil, so that’s 108 percent above that.”

“And of course the market did not like the signal that it got this week or late last week of the cancellation of the offshore lease sales in the Alaskan lease sales,” Helms said.

“For example, the RMPs, or the resource management programs, and the records of decision from Corps of Engineers and Forest Service weren’t filed along with information about why various quarterly lease sales were canceled,” Helms said. “And why some of the tracts were chosen that were chosen to be in this latest lease sale.”

North Dakota is a few days away from a May 18 deadline for protests in the projected June sale, which has 15 parcels listed. If there’s a protest against one or more of the tracts, they could be pulled from the sale for further consideration.

Rig Operator Well Name & Number Current Location County File No API Start Date Next Location fullCounty twp rng sec qq lat lng geometry

Rig Operator Well Name & Number Current Location County File No API Start Date Next Location fullCounty twp rng sec qq lat lng geometry

DISCLAIMER AND TERMS OF USE: HISTORICAL DATA IS PROVIDED “AS IS” AND SOLELY FOR INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES – NOT FOR TRADING PURPOSES OR ADVICE. NORTHDAKOTARIGSMAP.COM WILL NOT BE LIABLE FOR ANY DAMAGES RELATING TO YOUR USE OF THE DATA PROVIDED.

CountryUnited StatesCanadaAbkhaziaAfghanistanAland IslandsAlbaniaAlgeriaAmerican SamoaAndorraAngolaAnguillaAntigua and BarbudaArgentinaArmeniaArubaAustraliaAustriaAzerbaijanBahamasBahrainBaker IslandBangladeshBarbadosBelarusBelgiumBelizeBeninBermudaBhutanBoliviaBosnia and HerzegovinaBotswanaBrazilBritish Virgin IslandsBruneiBulgariaBurkina FasoBurundiCambodiaCameroonCape VerdeCayman IslandsCentral African RepublicChadChileChinaClipperton IslandColombiaComorosCongoCook IslandsCosta RicaCroatiaCubaCyprusCzech RepublicDenmarkDjiboutiDominicaDominican RepublicEcuadorEgyptEl SalvadorEquatorial GuineaEritreaEstoniaEthiopiaFalkland IslandsFaroe IslandsFijiFinlandFranceFrench GuianaFrench PolynesiaGabonGambiaGeorgiaGermanyGhanaGibraltarGreeceGreenlandGrenadaGuadeloupeGuamGuatemalaGuernseyGuineaGuinea-BissauGuyanaHaitiHondurasHong KongHowland IslandHungaryIcelandIndiaIndonesiaIranIraqIrelandIsle of ManIsraelItalyIvory CoastJamaicaJapanJarvis IslandJerseyJohnston AtollJordanKazakhstanKenyaKingman ReefKiribatiKosovoKuwaitKyrgyzstanLaosLatviaLebanonLesothoLiberiaLibyaLiechtensteinLithuaniaLuxembourgMacauMacedoniaMadagascarMalawiMalaysiaMaldivesMaliMaltaMarshall IslandsMartiniqueMauritaniaMauritiusMayotteMexicoMicronesiaMidway AtollMoldovaMonacoMongoliaMontenegroMontserratMoroccoMozambiqueMyanmarNagorno-KarabakhNamibiaNauruNavassa IslandNepalNetherlandsNetherlands AntillesNew CaledoniaNew ZealandNicaraguaNigerNigeriaNiueNorfolk IslandNorth KoreaNorthern CyprusNorthern Mariana IslandsNorwayOmanPakistanPalauPalestinian territoriesPalmyra AtollPanamaPapua New GuineaParaguayPeruPhilippinesPitcairn IslandsPolandPortugalPuerto RicoQatarReunionRomaniaRussiaRwandaSaint BarthélemySaint HelenaSaint Kitts and NevisSaint LuciaSaint MartinSaint Pierre and MiquelonSaint Vincent and the GrenadinesSamoaSan MarinoSao Tome and PrincipeSaudi ArabiaSenegalSerbiaSeychellesSierra LeoneSingaporeSlovakiaSloveniaSolomon IslandsSomaliaSomalilandSouth AfricaSouth KoreaSouth OssetiaSpainSri LankaSudanSurinameSvalbardSwazilandSwedenSwitzerlandSyriaTaiwanTajikistanTanzaniaThailandTimor-LesteTogoTokelauTongaTransnistriaTrinidad and TobagoTunisiaTurkeyTurkmenistanTurks and Caicos IslandsTuvaluUgandaUkraineUnited Arab EmiratesUnited KingdomUnited States Minor Outlying IslandsUnited States Virgin IslandsUruguayUzbekistanVanuatuVatican CityVenezuelaVietnamVirgin IslandsWake IslandWallis and FutunaWestern SaharaYemenZambiaZimbabwe

North Dakota’s tally of active oil and natural gas drilling rigs and hydraulic fracturing (frack) crews has risen to levels not seen since the start of the pandemic, the state’s top oil and gas regulator said Friday.

The rig count stood at 40 as of Friday, the highest since March 2020, North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) Director Lynn Helms told reporters.

Oil and natural gas production in the state rose by 3% and 4.5%, respectively, in March versus February. Oil output grew to 1.12 million b/d while natural gas output swelled to 3.0 Bcf/d, DMR data show.

Helms cited “extremely strong” prices for North Dakota Light Sweet crude oil, which stood at $101.75/bbl as of Friday. The price of natural gas delivered to TC Energy Corp.’s Northern Border pipeline system at Watford City, ND, stood at $6.34/Mcf, Helms said.

NGI’s Northern Border Ventura price, located on the same system but to the southeast in Ventura, IA, averaged $7.895/MMBtu on Tuesday (May 17), up from $2.815/MMBtu a year ago.

Helms highlighted that natural gas and oil storage inventories, both domestic and global, are well below historical averages, heralding continued high prices of each commodity.

The Bakken Shale and statewide natural gas capture rates both averaged 95% in March, with only a handful of non-Bakken areas showing substantially lower rates.

Drilling permits totaled 55 in April, down from 65 in March, while well completions fell to 33 from 53. The drop in completions was no surprise, Helms said, given two back-to-back blizzards that occurred last month. The blizzards are expected to substantially impact April production figures, he said.

The state’s drilled but uncompleted (DUC) well count continued to creep downward to 451 in March from 463 in February, part of a larger nationwide trend.

Workforce issues, meanwhile, remain “the number one barrier” to adding drilling and frack crews in the North Dakota oil patch, Helms said. “It’s taking around two months to train and deploy a drilling rig and crew, and pretty similar timeframes for frack crews,” he explained.

Helms also cited a lack of newbuild frack fleets since before the pandemic, saying, “the iron that’s out there is starting to show some wear and tear, some age. And at some point, we’re going to have to see capital deployed to bring that iron back on.”

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), for its part, is forecasting Bakken oil production of 1.17 million b/d in May and 1.19 million b/d in June. EIA is modeling Bakken natural gas production of 3.08 Bcf/d in May and 3.1 Bcf/d in June.

The Bakken’s leading producer, Continental Resources Inc., produced 171,401 boe/d in the shale play during the first quarter, up from 160,577 boe/d in the same period a year ago. In a presentation this month, Continental said it had six active rigs in the Bakken.

North Dakota oil production bounced back in May after getting hammered the previous month by ugly weather. The state pumped out 1.06 million barrels of oil a day, up 17% from April when back-to-back blizzards hit North Dakota.

"We have almost recovered what we lost in April," Lynn Helms, North Dakota"s minerals director, told reporters Tuesday. In May, North Dakota still was running below its March output of 1.12 million barrels per day.

Oil prices in May averaged more than $100 a barrel, meaning North Dakota oil tax collections remain healthy. West Texas Intermediate — the benchmark U.S. crude price — closed around $103 Tuesday.

North Dakota"s drill rig count, a harbinger of future oil production, currently stands at 42, the same as in June, but ahead of May"s tally of 40 and April"s 38.

The state still is short of the drilling activity it would need to grow production at a 2% annual rate. Helms said the optimal number of rigs for that output target is 50 to 55.

At that level of production, about 25 fracking crews — who pump oil from the ground after wells have been drilled — would be needed. Currently, there are 18 crews, and the oil companies are struggling to find more workers, Helms said.

"In the absence of a nationwide recession, which would send a lot of unemployed people to North Dakota, we will have to grow our own workforce," Helms said.

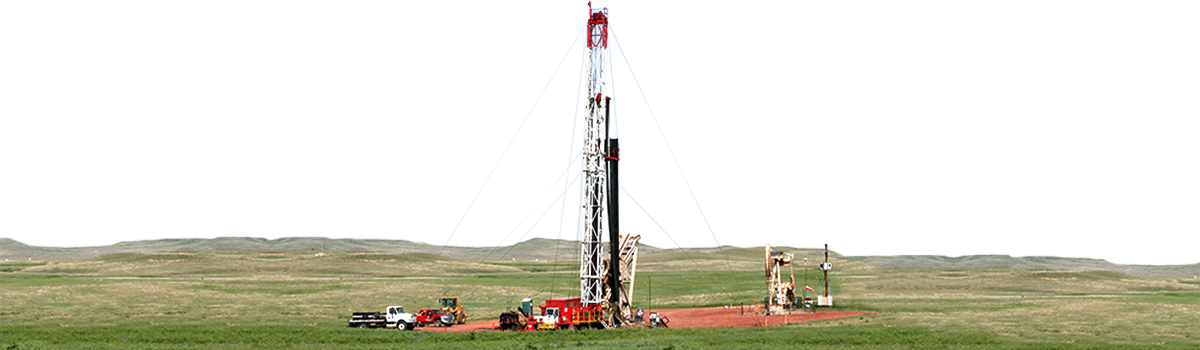

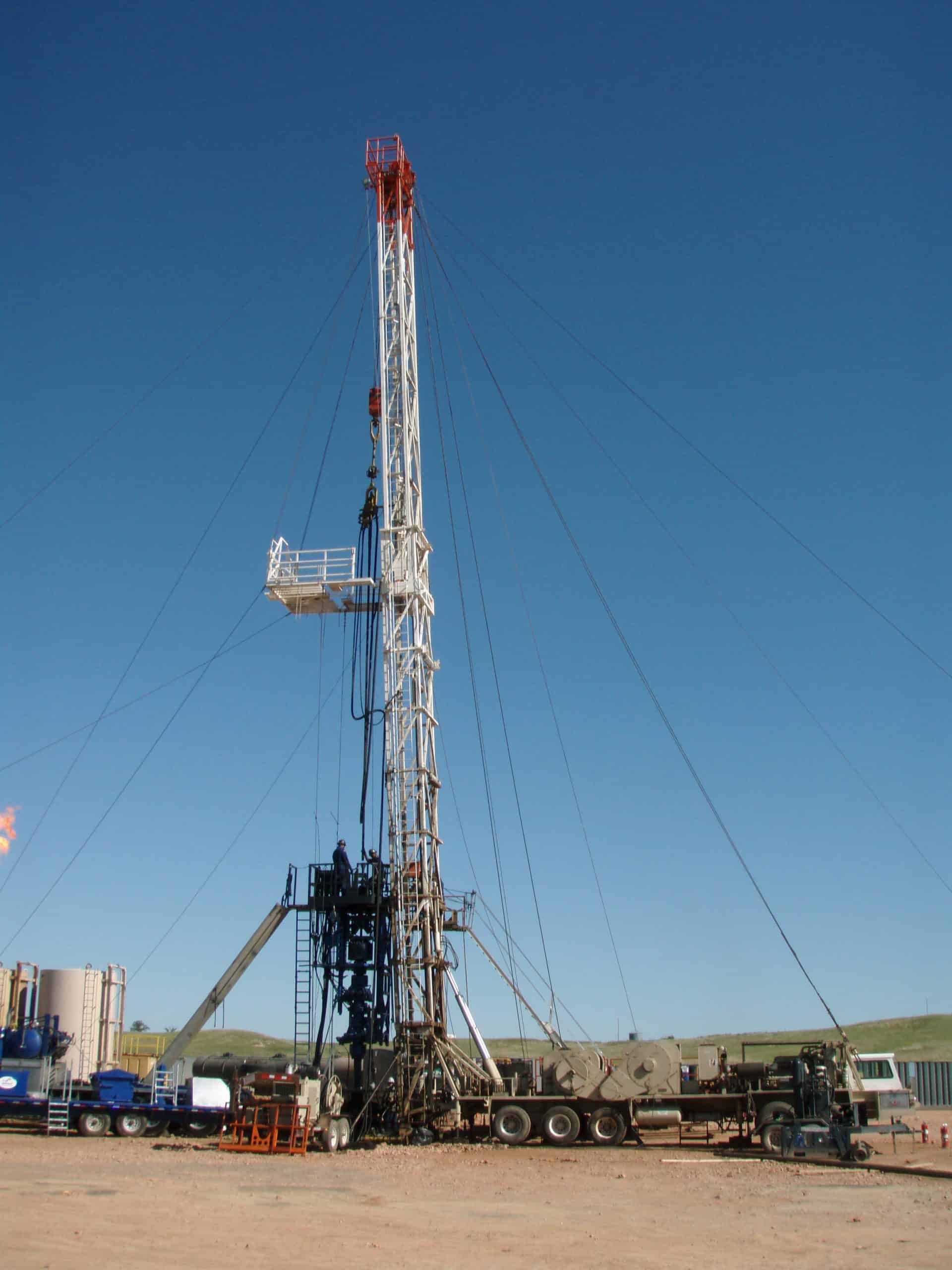

Oil Rig: An oil rig (also called drilling rig) is a large structure that contains the equipment necessary to drill holes into the ground in order to bring oil to the surface. Photo courtesy of Whiting Oil.

By 1990, the price of oil had increased, but extraction from the deep shale rock was not as efficient or profitable as it would become with advanced drilling technology.

This technology is similar to earlier horizontal drilling, but the new technology has made it possible for oil companies to drill down two miles (10,560 ft.) and then angle the instrument horizontally for another two to three miles.

Extended Reach Horizontal Drilling: Most drilling in North Dakota happens 2 miles below the surface and extends out another 2 miles. Graphic courtesy of the North Dakota Petroleum Council and the North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources.

Active wells in ND: This map shows the wells drilled in North Dakota as of January 2014. Map courtesy of North Dakota Industrial Commission Oil & Gas Division.

These wells supplied energy for some small towns, such as Mohall, Westhope, Lansford, as well as for nearby farms.Natural gas was used in China around 500 B.C. The Chinese people transported natural gas in bamboo pipelines for use in boiling sea water to extract salt.

Before natural gas can be used as a fuel, it is processed to remove impurities.Natural gas is sold in cubic feet (cu.ft.) measured at 60⁰ F and 14.73 pounds per square inch (psi). About 1,000 cu.ft. of natural gas can supply an average home for four days, depending on the season.

The U.S. rig count has gained one more rig in the last week to reach a total of 707 active drilling rigs. This count is up just 1% over the last month, but up 155% in the last year. The most notable rig increases are unfortunately not in the Bakken, however the rig count is currently at 33 in North Dakota which is an increase from the 10 operating rigs we had at this time last year.

At the time this article was written WTI Crude oil is sitting just over $78 per barrel, which represents a major improvement over the $52 per barrel prices that were seen at this time last year. While many factors go into the price of oil, most recently, factors such as improved risk sentiment and the global energy crunch appear to be the driving forces behind keeping prices stable for now. Even with OPEC enacting a slight output hike, prices appear around $80 appear to be here to stay during the winter.

Where are oil prices going from here? While we wish we had a crystal ball to tell us this we do have several key points we can look at to help us see where the market feels the prices of oil may be going in the near future. Predictions were for a price forecast of $80 a barrel for the last quarter of 2021 and we are seeing that now. Due to natural gas shortages and a post-pandemic demand that is outstripping supply, we could very well be on our way to $100 per barrel oil.

As you may have heard, due to substantially increased activity in New Mexico, North Dakota gave up its spot as the No. 2 oil producer. What does this mean for North Dakota? The production drop in North Dakota is not the main driving force behind this. New Mexico currently has 62 more active drillings rigs than North Dakota. Per the North Dakota Industrial Commission, companies are starting to bring on additional frack crews and have a fairly substantial back log of drilled but not yet completed wells to frack.

In summary: While the oil industry as a whole was hit especially hard during the pandemic, many of the producers that had high debt loads were forced out of the market through sales or bankruptcies which has allowed these companies to reorganize and fine tune their development plans going forward. This combined with the current backlog of wells needing to be fracked should provide for substantial oil and gas development in North Dakota for many years to come.

BISMARCK, N.D. (KUMV) - Oil and Gas production numbers in North Dakota are trending in the right direction going into the summer months, according to Department of Mineral Resources Director Lynn Helms.

In the latest Director’s Cut report, the state produced nearly 1.1 million barrels of oil in June, which is a 3.5% increase. Gas capture figures also showed a 9.7% increase during that period. Helms said that while more production is expected throughout the year, workforce and oil prices remain challenges to see significant growth.

“We’re not anticipating a big spike or a ramp up in drilling activity, just a slow increase in rig count and frack crews or completion crew count taking us through the end of the year,” said Helms.

He cited a recent survey by the U.S. Energy Information Administration that said producers need oil prices to remain around $98 a barrel for them to substantially increase drilling. Today, the price is at $88 a barrel.

It’s no secret that North Dakota’s oil industry is booming. Advancements in hydraulic fracturing have helped Western North Dakota experience month after month of record-setting oil production, making for one of the fastest-growing economic expansions the U.S. has ever seen. With the region having one of the lowest unemployment rates in the country and generating over 75,000 new jobs in the past few years, thousands of workers have showed up searching for high-paying jobs. Oil field workers in the state saw an average annual wage of $112,462 in 2012. Competition has intensified since the boom started around 2007, but entry level rig workers still average about $66,000 a year, according to Rigzone, an industry information provider and job website.

Though the salary figures may sound appealing, be warned that few of these jobs are located in a cushy office environment or require a mere 40 hours a week. Most employees report working anywhere from 80 to 120 hours a week, and conditions in North Dakota can be brutal, with temperatures regularly dropping below minus 30 degrees during the long winters. Housing is difficult to find, and many workers live in man camps with shared bathrooms and dining quarters.

If you’re thinking about giving the oil industry a try despite all those warnings, what can you expect? Which jobs should you shoot for? Here’s a rundown of the highest-paying jobs in North Dakota’s oil industry. The data come from Rigzone and are averages based on total annual compensation, including overtime and incentive pay. Though the data are calculated using industry figures from around the country, we only included positions that can be found in North Dakota’s oil patch.

A drilling consultant is an expert in all types of drilling operations. To become one, you typically need a bachelor’s degree or higher in engineering or a related field and at least five to 10 years experience in the oil field. The job tends to require frequent travel.

Sometimes called a “company man,” this managerial/supervisor position involves overseeing day-to-day operations of a crew, including safety, budget and maintenance, and coordinating with the various contractors that work with the company. The job is largely held by senior oil and gas professionals with many years of experience.

A “workover” or “completion” rig is placed on a hole after it’s been drilled. It’s typically used to insert tubing or pipe into the hole, perform major maintenance operations and set up the infrastructure for a hydraulic fracturing job. It’s one of the more technically difficult jobs in the field and tends to require an engineering degree. A workover driller will also assess well performance and recommend solutions for optimizing oil production.

There are many types of engineers in the oil field. One of the highest paid is a reservoir engineer, which involves estimating oil reserves and performing modeling studies to determine optimal locations and recovery methods. Other high-paid engineering jobs include a drilling engineer (averaging $142,664 a year), petroleum engineer ($126,448 a year) and mud engineer ($109,803 year).

Rig managers tend to oversee and manage the crew that’s working on-site. The job could include prepping and managing the budget and making sure targets are met. A bachelor’s degree isn’t usually required, as most rig managers start at the bottom as a rig hand or roustabout and work their way up.

Geoscientists and geologists in the field study the composition, structure, process and physical aspects of the earth’s energy resources, including analyzing data and collecting samples. A bachelor’s degree or higher is required.

Coil tubing refers to the metal piping used in an oil well after it’s been drilled. The tubing needed to pump fracking fluid down a well, among other operations. A coil tubing professional provides technical support and overseas the operation from start to finish, and tends to work as a contractor with many different oil companies. No bachelor’s degree is required.

Well control specialists or well testers typically travel from site to site, setting up and taking down rigs; inspecting production levels and equipment; and testing flowback quality. No bachelor’s degree required, though strong analytical skills, computer skills and experience with Excel spreadsheets is needed.

These jobs involve the work done to a well to increase production, including the process of hydraulic fracturing, when a mix of chemicals is pumped down the well to create fissures in the rock formation. It helps to have a degree in organic chemistry, chemical engineering or many years of experience working on fracking operations.

In the early evening of Sept. 14, 2011, Jebadiah Stanfill was working near the top of an oil rig at a bend in the Missouri River in North Dakota. Jolted by a deafening boom in the distance, he swung around from his perch and saw a pillar of black smoke twisting into the sky.

Stanfill, a compact and muscular man in his 30s, descended to the ground and hopped into the bed of a red pickup driven by a co-worker. Bruce Jorgenson, a manager overseeing the work of Stanfill and his crew, jumped into the passenger seat, and they raced to the explosion.

A few minutes later, they reached the burning rig and pulled up next to Doug Hysjulien, who was wandering in a valley and clutching the front of his underwear. The rest of his clothes were gone.

Stanfill sprinted until he spotted Ray Hardy, who had been hurled into a patch of gravel. His skin was charred black and peeling. His nails were bent back, exposing the stark white bones of his fingers.

“He’s over there,” Hardy responded, gazing toward a field near the rig. Stanfill scrambled over a berm and waded through knee-high wheat until he found Michael Twinn, lying on his back naked and seared. His hair was singed and his work boots had curled up in the heat. He cried out in agony.

Brendan Wegner, 21, had been scrambling down a derrick ladder when the well exploded, consuming him in a fiery tornado of oil and petroleum vapors. Rescuers found his body pinned under a heap of twisted steel pipes melted by the inferno. His charred hands were recovered later, still gripping the derrick ladder. It was his first day on the rig.

Hardy died the next day of his burns. Twinn had his lower legs amputated. Dogged by post-traumatic stress disorder, he killed himself in October 2013. Each left behind three children. Hysjulien suffered debilitating third-degree burns over half of his body. He is the lone survivor.

To this day, the explosion – pieced together from interviews, court documents and federal and local reports – remains the worst accident in the expansive Bakken oil fields since the boom began in 2006.

Beyond the human toll from that day, which continues to haunt Stanfill and others, the 2011 explosion offers a striking illustration of how big oil companies have largely written the rules governing their own accountability for accidents.

Across the Bakken, deeply entrenched corporate practices and weak federal oversight inoculate energy producers against responsibility when workers are killed or injured, while shifting the blame to others. Oil companies also offer financial incentives to workers for speeding up production – potentially jeopardizing their safety – and shield themselves through a web of companies to avoid paying the full cost of settlements to workers and their families when something goes wrong.

An estimated 7.4 billion barrels of undiscovered oil is sitting in the U.S. portion of the Bakken and Three Forks formations of the Williston Basin, a 170,000-square-mile area that stretches from southern Saskatchewan, Canada, to northern South Dakota. North Dakota now ranks just behind Texas with the second-largest oil reserve in the U.S. Both states now account for half of all the crude oil production in the country.

But the boom also has been a serial killer. On average, someone dies about every six weeks from an accident in the Bakken – at least 74 since 2006, according to an analysis by Reveal, the first comprehensive accounting of such deaths using data obtained from Canadian and U.S. regulators. The number of deaths is likely higher because federal regulators don’t have a systematic way to record oil- and gas-related deaths, and the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration doesn’t include certain fatalities, such as those of independent contractors.

Only one energy operator that leases or owns wells has been cited for worker deaths in North Dakota or Montana over the past five years, Reveal’s analysis has found. Slawson Exploration Co. Inc. paid a $7,000 penalty in 2013 after a contract worker died in an explosion.

OSHA officials say they are concerned that plummeting oil prices in the past year are prompting energy producers to shortchange safety even more. To others, the deaths and injuries would be preventable if not for a combination of greed, inadequate training and lack of government oversight.

Oil companies offer financial incentives to workers for speeding up production, potentially jeopardizing their safety. Credit: Adithya Sambamurthy/Reveal

On the day of the North Dakota explosion in 2011, the job of Brendan Wegner and the three other workers of Carlson Well Service was to get the well to produce more oil. Carlson was hired by the well’s owner, Oasis Petroleum North America LLC, which is part of Houston-based oil giant Oasis Petroleum Inc.

Michael Twinn, an experienced floorhand on the rig, had told his co-workers soon after they started work that day that he was worried about the well because it was “talking,” meaning it was showing signs of being under pressure. He had warned Loren Baltrusch, an independent contractor hired through Mitchell’s Oil Field Service who was supervising the site for Oasis, that there might have been a buildup of hydrocarbon gas, according to Justin Williams, a lawyer for Doug Hysjulien, the lone survivor, and Wegner’s parents, who spoke with Twinn about his ordeal before he died. Carlson Well Service officials later would testify that Wegner and his crew were not trained to work on wells under pressure.

Oasis declined an interview, but in a written statement, spokesman Brian Kennedy said: “Pressure gauge readings confirmed that the well was in fact static when operations began. Any suggestion that Mr. Baltrusch or Oasis Petroleum might have knowingly put workers in danger is patently false.”

The day before the accident, Baltrusch pumped heavy salt water into the well to prevent volatile gases from escaping before the crew set to work the next day, OSHA documents show. But on the day of the explosion, the well started to overflow with oil as the crew inserted more pipes into the well hole. That’s when the workers saw the oil rocketing 50 feet into the air. Then the inferno. Then their bodies burning.

“It shook my whole shack,” Bruce Jorgenson said in an interview. He was in a trailer less than a mile away working for Oasis, which had hired him through RPM Consulting Inc. to oversee another well site. “I went outside to investigate; that’s when all I saw was just a fireball.”

“We needed to try to help them in any way we could,” Jorgenson said. “Ray (Hardy) just seemed in shock … and Mike (Twinn) was in a lot of pain; he was screaming.”

When he saw Doug Hysjulien, Jorgenson recognized him immediately. They had both lived in Powers Lake, North Dakota, at one point. “His skin was very red. At first, I thought it was strings from his gloves hanging off of his hands, but it was his skin.”

Jebadiah Stanfill helped load Hardy and Twinn into the back of a pickup. When they placed Hardy in the bed of the truck, the coarse lining sheared skin off his scorched back. Stanfill cradled Twinn as they raced across the cratered dirt road to an ambulance on the main road. The flames had turned their skin to wax.

“There’s been an accident at the rig, and your husband wants to talk to you,” Stanfill said urgently into the phone to Twinn’s wife before putting her on speaker.

An estimated 7.4 billion barrels of undiscovered oil is sitting in the U.S. portion of the Bakken and Three Forks formations. Credit: Adithya Sambamurthy/Reveal

The rig was still smoldering when federal investigators drove to the scene the next day and began their work. Staff from the small OSHA office that serves the area interviewed witnesses and company officials in an attempt to re-create the blowout.

In 2011, the year of the deadly explosion, the agency’s office in Bismarck, North Dakota, had five field investigators – compared with eight this year – to handle tasks ranging from fielding complaints about butcher shops to triaging construction site hazards, along with far more technical cases involving oil and gas. The office covers roughly 148,000 square miles in North Dakota and South Dakota, including more than 12,000 producing wells in North Dakota alone.

From the start, the agency’s focus mainly fell on Carlson Well Service, the North Dakota-based company that employed Brendan Wegner and his three co-workers. The well itself was owned by Oasis Petroleum North America.

Investigators took dozens of photographs and several videos of the smoking nest of pipes and bent rig. They sifted through Carlson’s internal company documents such as work invoices and researched the company’s equipment. Over the course of six months, investigators interviewed about a dozen people and drafted reports totaling more than 200 pages.

Part of their investigation included researching the equipment they were inspecting – on Wikipedia. OSHA’s safety narrative report on the accident includes diagrams and information credited to the website’s entries for “blowout preventer” and “pumpjack.”

In the end, OSHA inspectors gave Oasis Petroleum cursory attention in their reports. A handwritten note from an OSHA investigator shows that Loren Baltrusch killed the well, or temporarily closed it, the day before the explosion, yet he was deemed an independent contractor. This was key because it is difficult for OSHA to cite energy producers that do not have direct employees on a worksite.

Instead, OSHA penalized Carlson for failing to properly install and test the blowout preventer, a mechanism that can help control an oil and gas well, as well as failing to provide flame-resistant clothing and an emergency escape line for Wegner to abandon the rig.

None of these steps would have prevented the accident in the first place, said Williams, adding that Oasis bore ultimate responsibility for making the proper engineering decisions that would have prevented the dangerous pressure buildup.

“It’s a simple engineering calculation,” he said. “They should have people qualified to do so, but they didn’t do that to start with.” Williams added that an expert he consulted said it would have taken no more than three tanker trucks of heavy brine water, costing about $1,500 combined, to properly kill the well.

Oasis’ Brian Kennedy said it was Baltrusch who arranged and oversaw the salt water injections – both the day before and the morning of the explosion – which he maintained rendered the well “static when work began.”

In March 2012, Carlson was fined $84,000, in part for failing to provide required safety equipment. The company’s lawyers hit back, arguing that one of the violations was not “willful,” as OSHA investigators had claimed. After negotiations, federal officials reduced that fine to $63,000. A top Carlson official declined to comment on the accident or OSHA fines. Carlson sold its business last year.

Like Carlson, many smaller contractors in the Bakken often receive fines, rather than the energy producers that own and lease the wells. Even though large companies often exert the most control over safety on their well sites, there is no specific federal workplace safety standard that applies to the oil and gas industry, which allows producers to dodge severe penalties.

In 1983, OSHA proposed workplace safety requirements for the oil and gas industry, but the rules never were imposed, leaving a “bit of a hole,” said Eric Brooks, director of OSHA’s Bismarck Area Office. As a result, OSHA primarily relies on the so-called general duty clause, which requires all employers to provide a safe workplace.

By contrast, the mining and construction industries are subject to stringent federal workplace safety regulations that address specific hazards. In fact, the Mine Safety and Health Administration enforces specific health and safety rules for the nation’s mines to reduce deaths and injuries.

In the absence of comprehensive workplace safety regulations, OSHA frequently invokes standards written by the industry itself, including those from the American Petroleum Institute, to determine whether employees are being exposed to hazards.

For example, companies involved in drilling and well servicing activities such as hydraulic fracturing are exempt from federal workplace safety laws requiring machines and equipment that are undergoing maintenance or repairs to be locked and tagged to prevent injuries. The American Petroleum Institute recommends such practices but does not require them.

“This premise is counterintuitive to the intent of government oversight. The problem with this scenario is that API is the lobbying arm of the industry,” said Dennis Schmitz, a former oil worker who is the chairman of the MonDaks Safety Network, an organization in North Dakota that promotes safety in the oil fields.

Following the accident, OSHA investigators interviewed Oasis officials and scrutinized Baltrusch’s role to determine how much control Oasis exercised over Carlson’s crew, Brooks said. OSHA didn’t fine the company because “in the absence of federal laws directly covering work on oil and gas sites, we couldn’t support a citation against Oasis,” Brooks said.

Brooks said that given another chance, OSHA likely would reverse itself and penalize Oasis. “If I had to look back on it, do I think things would be done differently? Absolutely,” he said. “I think we might have taken our chances and issued citations on that.”

After major accidents like the one that killed Ray Hardy and Brendan Wegner, big oil companies are insulated from financial costs. A spiderweb of corporate relationships allows big energy firms to shield themselves from collateral damage by forcing insurance companies for contractors at the bottom of the pecking order to pay.

Even though the government did not cite Oasis for responsibility for the accident, the company negotiated four separate settlements for undisclosed amounts with Wegner’s parents, Peggy and Kevin; Doug Hysjulien; Michael Twinn; and Hardy’s wife. During this process, disputes arose over who should pay the victims.

So the companies and their insurers took it to federal court. In the first lawsuit, Carlson Well Service argued that it should not have to defend or indemnify Oasis under their contract. The case ultimately was dismissed in June 2013 as part of a confidential settlement agreement.

In a second case, filed in the same court on the same day, Carlson’s insurance company argued that it did not have to pay damages to the injured workers on behalf of Oasis. In the end, Carlson’s insurance company agreed to share part of the settlement costs with Oasis’ insurance company, interviews show. The insurance company for Mitchell’s Oil Field Service, Loren Baltrusch’s employer, also contributed to the settlements.

“We found a way to protect Oasis,” said Kevin Cook, a Texas attorney who represented Carlson’s insurance company in the lawsuit against Oasis and its insurer in North Dakota federal court. “We resolved our differences with Oasis and their insurer by agreeing with them to divide these settlements.”

To Peggy Wegner, the shifting responsibility and finger-pointing means that Oasis “has never been held accountable” for the accident that killed her son. “It’s just another way to cover their ass,” she said. “It’s bizarre to me that a contract like this can even take place.”

In a more recent case, for example, Continental Resources Inc. won a favorable decision in February following a well blowout that injured three contract workers in July 2011 near Beach, North Dakota. The workers’ employer, Cyclone Drilling Inc., had signed a contract containing an indemnity provision in favor of Continental that was unlimited and without regard to the cause of the accident, according to the agreement.

In addition, Cyclone’s insurance policy included coverage for Continental protecting it from paying the cost of any suits brought by Cyclone’s workers who were injured or families of workers killed on the job. As a result, a federal judge allowed Continental and its contractors to shift up to $6 million for the workers’ injuries to Cyclone’s insurance company, court records show.

“As to the cause of the incident the public records show who was cited,” Eric Eissenstat, Continental’s senior vice president, general counsel, chief risk officer and secretary, said in an email.

If the top energy producers that control sites with fracked wells – in which oil and gas are extracted from shale with high-pressure mixtures of water, sand or gravel and chemicals – are permitted to offload the responsibility to smaller contractors, then there is little incentive to make worksites safer, said Paul Sanderson, a North Dakota attorney who frequently has encountered these agreements.

This phenomenon seems to be lost on the federal regulators who cover the Bakken. Asked whether these agreements could make energy producers indifferent to worker safety, Eric Brooks, OSHA’s Bismarck office director, said of the practice: “I’m not aware of that at all.”

“The Bakken is the most dangerous oil field to work in the U.S.,” Williams said. “The energy producers never pay for their mistakes; the insurance company for the contractor pays. It doesn’t give them any incentive to change the procedures that are unsafe.”

While Oasis contends that Carlson Well Service was largely at fault in the 2011 explosion, the contractor’s experience afterward is not uncommon. Smaller contractors have little choice but to agree to the terms in their contracts. Their insurance companies often end up shouldering part or all of the costs of settlements with workers and their families.

“This bill could have saved lives. When everyone is held responsible for their own conduct … it’s going to create a safer work environment.”— Paul Sanderson, North Dakota lawyer

“The big oil companies have you locked in,” said Connie Krinke, business manager for Diamond H Service LLC, an oil and gas service company based in Bowman, North Dakota.

“You really don’t have the ability to refuse to sign these agreements because most of these companies are billion-dollar companies, and we’re just a small pea in the big pod of people that work for them,” she added. “They have really good lawyers.”

A bill proposed in the state Legislative Assembly in January 2011 sought to prevent companies from adding provisions to oil and gas production contracts that required smaller contractors to indemnify them when people are injured or die because of the action of the companies or their independent contractors.

“If you break it, you buy it,” said Paul Sanderson, a North Dakota lawyer who crafted the bill in response to growing concern among insurers following several oil field accidents. “When a person is not responsible for their actions, they disregard the consequences.”

The bill passed out of the House Judiciary Committee. But the effort was torpedoed nearly a week later after heavy lobbying from the oil industry, Sanderson said. The bill was unnecessary and interfered with contracting in the oil industry, a lobbyist for the North Dakota Petroleum Council argued at the time. The bill was defeated 63-27 on the House floor, state legislative records show.

Yet the dangerous nature of the oil and gas industry has prompted four of the largest energy-producing states – Texas, Louisiana, New Mexico and Wyoming – to adopt statutes that prevent or limit oil companies from shifting liability, including legal costs, jury awards and settlements for workers’ injuries or wrongful death suits, to smaller contractors.

Today in North Dakota, under some agreements, oil companies and smaller contractors indemnify each other, meaning each will shoulder the cost of claims for damages made by their own employees involved in accidents, regardless of who is at fault. But this works only if large companies dispatch direct employees to work on their well sites, which they often do not.

“This bill could have saved lives,” Sanderson said, adding: “When everyone is held responsible for their own conduct … it’s going to create a safer work environment. You have situations where the oil companies know they are not going to be held responsible.”

Bill or not, safety is the top priority for oil and gas companies in the Bakken, said Kari Cutting, vice president of the North Dakota Petroleum Council, which represents 550 companies. “Any language written in a contract is not going to change where safety is in their priorities. A lot of these companies are very savvy and don’t want to be the headline in any news cycle.”

Oasis’ company man the day of the 2011 explosion was Loren Baltrusch. Soon after the accident, he gave conflicting accounts to authorities and regulators of his precise role that day.

Soon after the interview begins, an unidentified man interrupts: “Hey Loren, that’s the guys in Houston; they’re very concerned about you,” he says in an apparent reference to Oasis officials. “You need to get checked out.

Baltrusch later told OSHA investigators that he was charged with consulting with Oasis on the engineering aspects and directing servicing activities on the well. But then he said he “really did not know what his authority was since it had never been explained to him,” OSHA records show. Baltrusch declined to comment.

This loophole has allowed Oasis and other energy producers to shift blame and protect their bottom lines from government fines when workers are injured or killed. They hire so-called company men to be their eyes and ears, executing orders and supervising drilling and other tasks.

“If you ask anyone who is in control at these well sites, they’ll tell you the company man,” said Eric Brooks, OSHA’s Bismarck office director. “They are dictating what you’re doing, how you’re doing it. They’re communicating every detail in real time to the companies about what’s happening with the drilling process.”

But because most of these managers are independent contractors, they are not covered under federal workplace safety laws. So company men generally allow energy producers to duck federal fines for accidents.

“Company men became independent contractors to protect the company,” said Tom Dickson, an attorney in Bismarck who has represented dozens of workers in personal injury and wrongful death suits. “They’re not accountable to anybody when something bad happens. It protects the top dog from accountability.”

That’s what happened after an explosion at the Zacher oil well in Mountrail County, North Dakota, in 2007. EOG Resources Inc., formerly known as Enron Oil and Gas Co., was using an open-top tank to reclaim wastewater from a fracking well to save money, according to court records.

When EOG’s company man, Paul Berger, decided to jump-start a defective light tower late one evening, gas vapors wafting from the experimental tank ignited, scorching the crew. Berger said he was under pressure from EOG to get the well flowing, according to a deposition.

After the explosion, EOG prevailed in a lawsuit in federal court in North Dakota, arguing that a provision of its contract required its contractors to indemnify the company, the well’s owner and operator, against other lawsuits that three injured workers had brought against EOG. While EOG ultimately controlled the well site, OSHA did not cite or fine the company.

Few suffered the consequences of that thirst for cash more than Ted Seidler, one of the workers injured at the EOG site, who underwent a series of operations after he was burned on his hands, legs, face and backside.

“It was hell,” Seidler said in a phone interview from his home in North Dakota. “It was a whole year that I never worked because of the burns. My wife quit her job to take care of me.”

Seidler, 66, tried to return to his old job. But the confluence of North Dakota’s extreme temperatures and his tender skin forced him to quit the oil fields. In 2009, Seidler settled with EOG and several of its contractors for an undisclosed amount after filing a lawsuit in state court.

“Everybody was passing the buck,” Seidler said. “They shouldn’t be allowed to do that. EOG should be the one who should be held accountable for the whole deal because they are the owners of the well.”

There have been at least 74 deaths in Bakken accidents since 2006, according to a Reveal analysis using data from Canadian and U.S. regulators. Credit: Adithya Sambamurthy/Reveal

Oasis provides workers with financial incentives to drill quickly and has lavished them with praise for setting records when they reach target well depths.

Four months before Brendan Wegner died, Joseph Kronberg, a 52-year-old father of three, was electrocuted and died at another North Dakota well owned by Oasis Petroleum North America.

Oasis paid bonuses worth a combined $33,000 to 23 of Kronberg’s co-workers in part for working quickly – even after Kronberg died, internal company records show. At a well on the same site where Kronberg died and another nearby well, Oasis paid workers performance bonuses of $150 per day for drilling quickly, compared with $40 a day for drilling safely, records show.

“Safety is tantamount at Oasis,” spokesman Brian Kennedy said, but when pressed, he acknowledged that in the case of Kronberg’s co-workers, “bonuses should not have been paid, and we regret that they were.”

“Nabors 149 just set a new record for Oasis on the Kline with Stoneham 18 following close behind on the Lynn. Congrats guys, keep it up!!” Laura Strong, an Oasis drilling engineer, wrote in a May 27, 2011, email to top company officials and company men.

“If you have a bonus that is simply based on getting it done faster… you’ve got a recipe for disaster.”— Eric Brooks, OSHA’s Bismarck Area Office director

In a lawsuit filed in January 2013 in federal court in North Dakota, lawyers for Kronberg’s widow, Margo, asserted that the company fosters a culture of recklessness in which there is one imperative: speed.

In court papers, lawyers for Oasis said Nabors Drilling USA LP, a contractor, would be required to cover the cost of any judgment in the case under its drilling contract. A federal judge concluded that Oasis was not responsible for Joseph Kronberg’s death, concluding that Oasis didn’t exercise a sufficient degree of control over the company man or any of the smaller contractors on site.

In the case, the judge reviewed a string of emails between Oasis and its company men, but ruled that they “merely constitute evidence as to Oasis’ end goal for the Ross well.” In addition, the judge ruled, Oasis did not owe a duty to exercise reasonable care to prevent this kind of accident.

Margo Kronberg was prevented from suing Nabors under North Dakota law, which generally prohibits employees who are injured on the job and their families from suing their employers.

Insiders overseeing drilling in the Bakken oil fields say Oasis is not the only company that pays bonuses for increasing production and profit. They say top companies such as EOG, Whiting Petroleum Corp. and many others also dole out incentives.

On EOG sites, for example, some workers earn $1,600 to $3,000 for “beating the curve,” or rapidly drilling their wells, according to two workers who declined to be identified for fear it would jeopardize their jobs.

“Over the past five or six years, there’s been a culture that’s been primarily focused on the production side,” said Dennis Schmitz of the MonDaks Safety Network. “There’s been a culture of gettin’ it done.”

Among the most common oil field injuries are amputations, broken bones and burns, which can severely disfigure workers and diminish their career prospects, OSHA’s Eric Brooks said. Despite the dangers, workers are drawn to the Bakken for hefty salaries, some in the six figures.

Drilling and well servicing in the Bakken is high stakes, at an average cost of about $9 million per well, according to the North Dakota Industrial Commission’s Department of Mineral Resources. The faster the oil gushes, the faster it gets to market to turn a profit, which averages $27 million per well.

That was true when oil was $100 a barrel. And now that oil has slipped to about $60 a barrel, that pressure has intensified, Schmitz said. In addition, with slimmer margins, Schmitz said several companies have fired their safety managers.

On their websites, many energy producers promote a “stop work” culture, in which workers are encouraged to speak out and stop the job if they deem something unsafe. But dozens of workers interviewed in the Bakken said that when they’re drilling, time is money.

“You’ve seen that in a lot of the accidents that happen out here, guys saying yes and meaning no,” said Matthew Danks, vice president and partner of Oilfield Support Services, a New Town, North Dakota-based company that builds facilities after wells are drilled to separate oil, gas and water.

Asked about speed bonuses, Brooks said that while he has not seen any specific examples, he would consider asking his investigators to scrutinize the practice.

For his efforts in trying to save his brethren, Stanfill says he was fired from his job at Xtreme Drilling and Coil Services Corp. Stanfill said he was told by managers at Xtreme and Oasis that he’d gone beyond his “scope of employment.” He should have remained on his own rig instead of rushing to the scene.

Oasis spokesman Brian Kennedy said: “As Mr. Stanfill was an employee of Xtreme Drilling and not Oasis Petroleum, we were not party to or responsible for any decisions regarding his employment.”

Benjamin Smith, Xtreme’s vice president of human resources, said Stanfill’s claim is “bogus.” Instead, Smith said Stanfill was fired for turning off a valve that cut power to a drilling rig, which he said endangered other employees – a claim that Stanfill dismissed as “a bald-faced lie.”

“Why would I put my life on the line for those men on the burning rig and then turn off the power on a rig so that my own co-workers will die?” Stanfill said. “That makes no sense. I don’t even know how to turn off a rig.”

Now a handyman living in Alabama, he said he still struggles with PTSD, often wearing black work gloves to prevent the sight of his hands from triggering memories of skin sliding off in his palms.

When Bruce Jorgenson returned to the site this past March to start drilling the new well, “the anxiety came back. I relived every minute of it. I’ve been involved in other bad things in the oil field, and this one was the only one that gave me nightmares.”

Even so, Jorgenson said he hasn’t discussed the explosion with his current crew. “I didn’t want them freaked out by it in any way. I wanted their mind on what we were doing.”

Jennifer Gollan can be reached atjgollan@revealnews.org. Follow her on Twitter:@jennifergollan.Taking on powerful interests demands lots of time, a strong backbone and your support.

BISMARCK, N.D. — Another dip in oil prices Monday, briefly touching a five-year low at less than $50 a barrel, caused an upset in the stock exchange and focused more attention on response by companies drilling the Bakken in North Dakota.

Some of that slowdown may be seasonal, but some can be attributed to companies laying off rigs while watching what happens in the oil market. Bakken oil is discounted another $10 to $16 a barrel because of transportation costs.

One major Bakken producer, Continental Resources, recently announced it will cut its Bakken rigs by half of what it had planned for 2015, down to 11 from the 19 rigs it expected to have drilling under an earlier forecast.

On the other hand, company owner Harold Hamm said he still expects to complete 188 Bakken wells this year while oil well service costs, which include hydraulic fracturing, should decline by 15 percent.

Hess Corporation spokesman John Roper said his company has 17 rigs drilling in the Bakken and was still hiring as of last week, despite rumors of layoffs in the oil patch.

A December company investor presentation said Hess expected to have 14 rigs drilling during 2015 and Roper said Hess will update its investors about 2015 drilling activity sometime in January.

A company release says: "Expected impacts to oilfield service costs plus the change in crude oil (prices) warrants additional time before finalizing our 2015 budget."

Whiting Petroleum, which recently completed the purchase of Kodiak Oil & Gas Corp. to become the largest Bakken oil producer, says much the same thing in this release: "Given volatile oil prices, we intend to issue final 2015 guidance…in February."

In mid-December, Lynn Helms, North Dakota"s top regulator, said he expected the rig count could drop by as many as 30 to 45 over coming months. Half that low-end estimate was reached the first week in January.

For those people who may think that drilling oil wells in McKenzie County could be slowing down in the near future, a new report released by the North Dakota Dept. of Mineral Resources shows another 10,844 wells could be drilled in the county in the next 13 years, which may give them cause to reconsider.

According to Lynn Helms, director of Mineral Resources, McKenzie County is projected to have 13,500 wells by 2027. To put that growth into perspective, McKenzie County had 2,656 in production in July of this year, while there are now 11,287 producing wells in all of North Dakota.

Speaking to the North Dakota Association of Oil and Gas Producing Counties (NDAOGPC) in Williston on Sept. 18, Helms said that projections show continued strong growth in the four core oil and gas-producing counties of Mountrail, McKenzie, Williams and Dunn. He also said that non-Bakken-producing counties like Bottineau and Bowman can also expect a continued slow growth of about one to five rigs during the next two years.

And those projections, according to Watford City Mayor Brent Sanford and County Commission Chairman Ron Anderson, mean just one thing. And that is that there is not going to be any let-up for another 10 years.

“They (the Dept. of Mineral Resources) just doubled the numbers, just like that,” states Sanford. “We’re not going to see any decrease in oil activity until 2027.”

“With those kind of well numbers and job numbers, everything is doubling for Watford City,” says Sanford. “We’re going to need more of everything and we’re going to need more money to get all of the work done.”

According to Anderson, it’s because McKenzie County is literally in the sweet spot of the Bakken and Three Forks formations and has the highest producing oil and gas wells.

Anderson also noted that according to Helms, because of the high production of the McKenzie County wells, the break-even point for oil companies is much lower.

“Helms said that the break-even point for wells in McKenzie County is $37 a barrel,” stated Anderson. “In other areas of the Bakken, the break-even point is closer to $70 per barrel.”

So with higher production and the chance of greater profitability in the event that oil prices should drop, there is going to be a hesitancy on the part of most oil companies to leave McKenzie County.

“We know that every time that we have seen well and job projections in the past, those numbers have been too conservative,” states Sanford. “One would assume that these new numbers could also be too low.”

Two other factors, according to Anderson, that could lead to more wells and jobs than what is now being projected, is improved drilling technology and the development of other formations.

“We know that technology is improving all the time when it comes to drilling wells,” states Anderson. “And the oil companies know that there are at least three other oil formations that are lying under the Bakken and Three Forks formations.”

8613371530291

8613371530291