apollo 11 mission parts supplier

When the Apollo 11 spaceflight departed the Kennedy Space Center on July 16, 1969, it was carrying three astronauts, mankind’s aspirations to finally land on the Moon, and sophisticated equipment that made it all possible. Prior to the historic spaceflight, NASA contracted several companies to build the Saturn V launch vehicle, the Apollo spacecraft that landed on the Moon on July 20, and the Apollo ground control center in Houston. The Dallas based Texas Instruments was one of the subcontractors that supplied parts for all three components of the Apollo 11 mission.

performance of the equipment in Apollo 11,” while holding one of the switches on the control panel of the command module -the capsule that brought the astronauts back to Earth. The switch, TI World proudly pointed out, had been produced by TI’s Control Products division in Attleboro, MA, one of a total of approximately 800 switches required by the space mission. Hundreds of TI’s small signal transistors, silicon and germanium power transistors, computer diodes,, miniature thermostats worked without a hitch to ensure the success of the spaceflight and Moon landing. While it didn’t actually go to the Moon or even outside of Dallas, the data signal conditioner in the image is an example of an integrated circuit similar to the luckier ones that were selected for space travel.

Data and image recording devices built using TI components are essential in the recording and transmission of information taken by the space probes Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, which were launched in 1977, and have since traveled beyond the known planets and into the interstellar space. The Hubble Space Telescope pictured here uses TI built imaging chips.

To do that, several companies either opened or expanded operations in Central Florida. So the moon mission brought companies such as Martin Marietta, Grumman and Lockheed into the forefront of the region’s economy.

“It improved transportation,” Handberg said. “A lot of people decided to live in Central Florida and commute to the Cape during Apollo and later the shuttle.”

That growth was only natural in an area watching a new industry develop, said Charlie Mars, who was NASA’s program chief for the Apollo’s lunar module.

As the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission to the moon approaches, here is a look back at some of the companies that came here to support the iconic program.

Martin Co. merged with American Marietta Corp. in 1961 to become Martin Marietta, which built the Viking Mars Lander. That vehicle became the first to touch down on the Red Planet and successfully executed its mission in 1976. With its Central Florida location, Marietta competed - and ultimately lost out to Grumman - for the lunar lander.

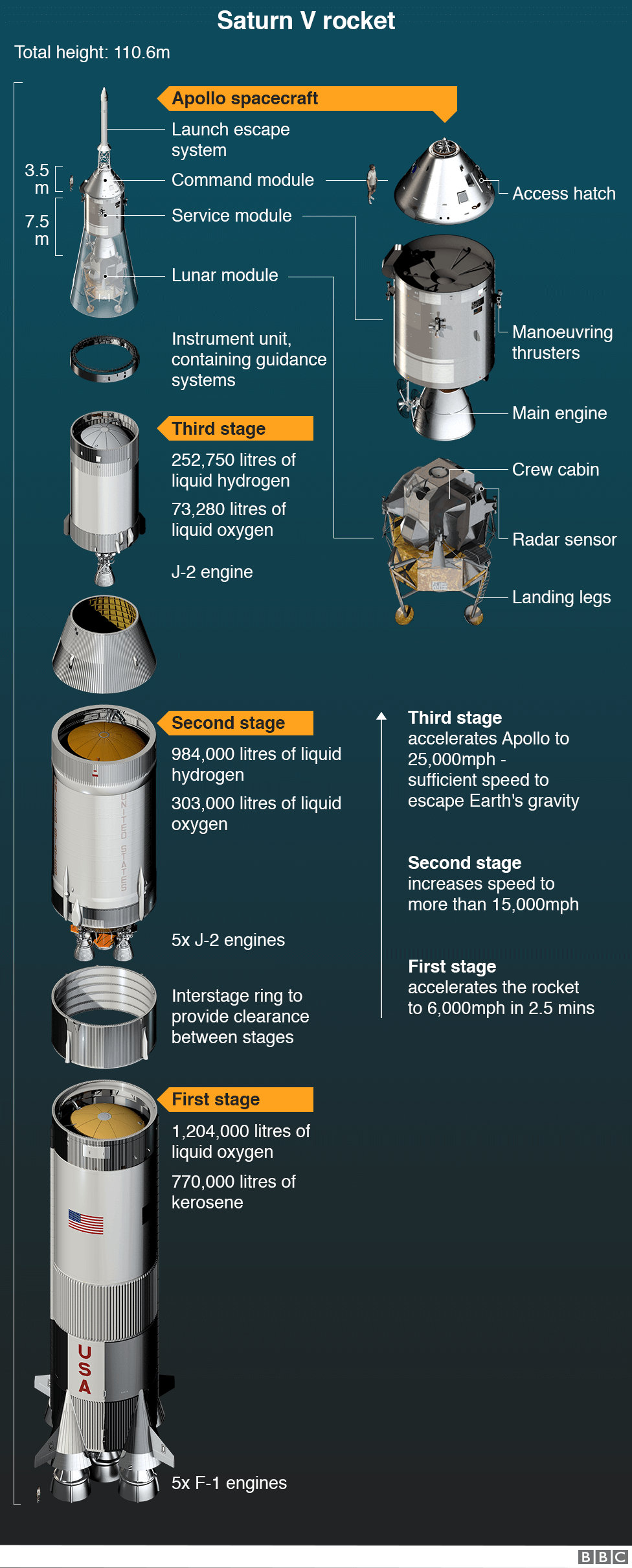

Boeing, along with firms like McDonnell Douglas and Rockwell International that it eventually merged with, built most of the major components of the Apollo spacecraft, including all three stages of its Saturn V rocket.

Boeing sent a lunar orbiter to take pictures of the moon’s surface ahead of the first landing mission. Boeing last month announced that it would relocate its space and launch headquarters to the Space Coast.

Harris Corp.’s presence in Melbourne predates the Apollo program. However, it landed several contracts for the mission, primarily for communications gear that allowed astronauts to contact ground control from the moon.

The propulsion, escape and pitch control systems for the Apollo spacecraft were built and designed by Lockheed Propulsion Co., shortly before the company built Walt Disney World’s first monorail system in 1970. Today, Lockheed Martin employs 8,000 workers in Central Florida and expanded its workforce at its Cape Canaveral site in 2015 to support a missile contract with the U.S. Navy.

Aerojet was a predecessor of what is now Aerojet Rocketdyne and created the solid fuel technology used in Apollo’s Saturn V first stages. In 1963, the company landed $3 million from the U.S. Air Force to build a manufacturing and testing site in Homestead. When the company designed a rocket motor, it was transported by barge to Cape Canaveral.

Grumman Corp. first arrived in Central Florida to support Apollo in the 1960s. The company, now known as Northrop Grumman, built the lunar lander that ferried astronauts to the moon’s surface 50 years ago. That deal was valued at $350 million when it was first awarded.

The lander became what some experts have called the most reliable component of the Apollo missions. About three years ago, Grumman announced it would expand its Space Coast facilities to accommodate nearly 2,000 new employees at Orlando Melbourne International Airport after landing a contract to build the U.S. Air Force’s next-generation bomber.

This story is part of the Orlando Sentinel’s “Countdown to Apollo 11: The First Moon Landing” – 30 days of stories leading up to 50th anniversary of the historic first steps on moon on July 20, 1969. More stories, photos and videos atOrlandoSentinel.com/Apollo11.

The Apollo Lunar Module, or "LEM" for short, was a highly specialized spacecraft built by Grumman Aircraft Engineering which was designed to land on the lunar surface and return the astronauts to the Command Module in lunar orbit for their trip back to Earth.

At the time, very little about the actual moon spacecraft itself was baked. When compared to the Saturn V rocket itself, it was the least developed part of the entire Apollo system in terms of concept and planning. Additionally, at the time, very few aeronautics contractors knew anything about building actual spacecraft, let alone something that could land on the moon and bring the astronauts home.

Nobody at Grumman had any experience with spacecraft, so this was entirely new territory for the company. However, the Grumman engineers working on the Apollo proposal response had read some early papers by NASA engineers Tom Dolan and John Houbolt who had proposed what is now known as a Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR) mission profile.

LOR was one of three mission profiles considered for the moon landing and was not the front runner for consideration. The others were Earth Orbit Rendezvous and Direct Ascent, the latter of which was the initial candidate.

A "Buck Rogers" style for Direct Ascent as shown in many early Science Fiction movies of the period would have been too expensive and very difficult to engineer within the schedule-driven constraints of the Apollo Program. The EOR profile had its merits, but once LOR had been proven as viable, it was chosen as the mission profile for the landing.

The final design iteration, integrating hundreds of significant design alterations went into production in April of 1963. The first LM was flight tested in Earth orbit on January 22, 1968, aboard the Apollo 5 mission, and the first actual lunar descent test occurred during Apollo 10 in May of 1969, only two months before Apollo 11.

After the Apollo program, Grumman resumed its work on fighter aircraft for the Navy, such as the F-14 Tomcat multi-role interceptor and the E-2 Hawkeye all-weather Airborne Early Warning aircraft which continues to be refined and used by the Navy to this very day.

the astronauts, astronaut, lunar landing, moon landing, walk on the moon, apollo 11 landing, armstrong s, manned, apollo program, men on the moon, one small step for man, the eagle, saturn v, man on the moon, tranquility, sea of tranquility, splashdown, saturn v rocket, pacific ocean, walk on, mission control, earth orbit, the sea of tranquility, space center, kennedy space center, apollo 11 moon landing, saturn, land on the moon, descent, man on the moon, first man on the moon, moon landing, the first man, astronaut, the astronauts, walk on the moon, the moon landing, lunar landing, men on the moon, armstrong s, one small step for man, mission control, first moon landing, land on the moon, walk on, manned, in space, safely, sea of tranquility, space race, the eagle, the space, edwin aldrin, nixon, apollo missions, kennedy space center, space center, the sea of tranquility, kennedy, moon landing, the astronauts, the moon landing, astronaut, first moon landing, one small step for man, man on the moon, lunar landing, land on the moon, on the surface, in space, faked, apollo program, apollo missions, sea of tranquility, apollo astronauts, saturn v rocket, landing on the moon, mission control, rocket, space center, first man on the moon, hoax, manned, descent, walk on the moon, the sea of tranquility, tranquility, saturn v, american flag... space exploration, july 16, the crew, launched, exploration, president nixon, space station, the space race, first moonwalk, journey to the moon, the pacific ocean, cape kennedy, moonwalk, moon rocks, aboard, the earth, the planet earth, kennedy s, mars, earth first, two men, spacesuit, orbiter, the descent, the flag, the kennedy, lander, into space, quarantine, the ladder...

apollo program, apollo missions, lunar landing, astronaut, the astronauts, moon landing, apollo spacecraft, apollo 8, apollo 1, man on the moon, unmanned, manned, men on the moon, skylab, landing on the moon, earth orbit, lunar mission, saturn v, soyuz, orbiting, land on the moon, in space, chaffe, saturn, schmitt, 1972, apollo 18, gus grissom, lunar rover, rille...

florida institute of technology, florida institute, mission to mars, institute of technology, the red planet, astronautics, cycler, phobos, the buzz, red planet, master plan, colonizing mars, mars settlement, florida tech, occupy, pathways, colonizing, 70th anniversary, colonize mars, massachusetts institute of technology, martian, asteroid, cycling, the institute, travel voucher, the martian, colonize, rendezvous, air force, settlement...

Vintage pictures of the crew of Apollo 11 mission signed by its three Nasa astronauts,Buzz Aldrin, Michael Collins, and Neil Armstrong, the first manto walk on the Moon, are for sale. This is nowaday normal. But how much is it worth ? 3000 $ ? 7000 $ ?

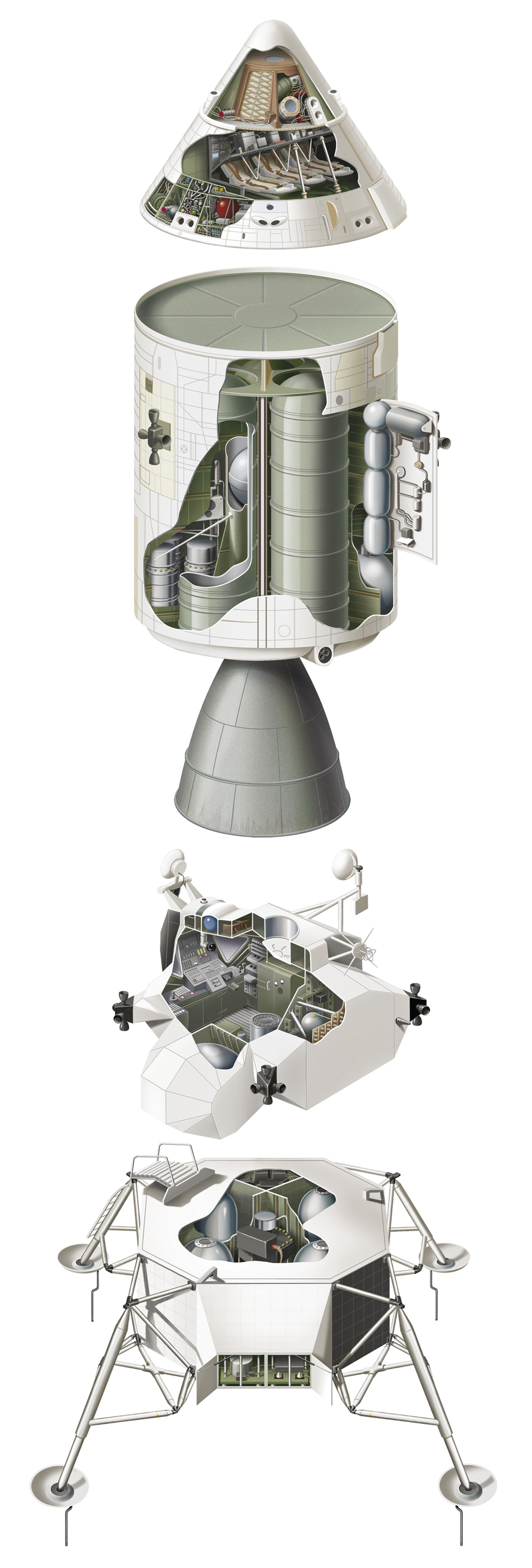

The Apollo 11 Command Module, "Columbia," was the living quarters for the three-person crew during most of the first crewed lunar landing mission in July 1969. On July 16, 1969, Neil Armstrong, Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin and Michael Collins were launched from Cape Kennedy atop a Saturn V rocket. This Command Module, no. 107, manufactured by North American Rockwell, was one of three parts of the complete Apollo spacecraft. The other two parts were the Service Module and the Lunar Module, nicknamed "Eagle." The Service Module contained the main spacecraft propulsion system and consumables while the Lunar Module was the two-person craft used by Armstrong and Aldrin to descend to the Moon"s surface on July 20. The Command Module is the only portion of the spacecraft to return to Earth.

It was physically transferred to the Smithsonian in 1971 following a NASA-sponsored tour of American cities. The Apollo CM Columbia has been designated a "Milestone of Flight" by the Museum.

As the astronauts of the Apollo 11 mission prepared to board their spacecraft, the support crew that aided their final preparations wore suits with "ILC Industries" stitched in large block lettering across the back.

As the 50th anniversary nears, NASA"s most recent efforts to bring man back to the moon are in question but the two Delaware companies that made the Apollo 11 mission possible are still making history.

Prior to the mission, Armstrong, Aldrin and Michael Collins, the third member of the Apollo 11 crew, made trips to ILC Dover"s Frederica headquarters to be fit for and test the suits. The suits were fully custom-built for each astronaut.

Two years into ILC"s tenure as NASA"s space suit provider, three astronauts died in a fire during a training exercise for the first Apollo mission. The deaths prompted ILC to completely reconfigure its spacesuit design.

"Each layer of material contributed something different for the overall performance and it was really the total suit coming together that made the mission possible," Norton said.

Since 2017, the agency has been working on the Artemis program — named after the twin sister of the Greek mythological figure Apollo. The effort requires a custom-built Space Launch System rocket, a platform orbiting the moon known as "Gateway" and a lunar lander system to take people to the surface.

The company has varied in size throughout its existence — peaking around 1,000 employees during the lead-up to Apollo 11 and dipping near 25 employees after the Apollo missions — but has long been at the forefront of innovation.

In 1977, ILC Dover won the contract to build suits for the space shuttle, which revived the company. Instead of being individually tailored, the new suits were made of interchangeable parts. The technology is the basis for the suits used today.

The spacesuit business, however, will forever be ILC Dover"s calling card. The company has produced more than 300 space suits. Each Apollo mission alone required 15 suits, three for each member of the first-string crew and two for each of their backups.

"They were and are nowhere near the size of DuPont, but they end up becoming the private contractor for the Apollo," said Clawson, the Hagley historian. "It’s fascinating to me how such a small company like that can have such a large affect."

Falling back from the moon at almost seven miles a second, the crew of Apollo 11 took it in turns to broadcast their thoughts about what their mission meant. Buzz Aldrin spoke not just of it being three men on a mission to the moon, but of their flight symbolising the insatiable curiosity of mankind to explore the unknown. Mike Collins talked about the complexity of the Saturn V and the blood, sweat and tears it had taken to build. And Neil Armstrong thanked the Americans who had put their hearts and all their abilities into building the equipment and machinery that had made the journey possible.

Many of these people had never worked in the aerospace industry, and none had worked before on machines designed to transport humans to another world. Overnight, as their companies won Apollo contracts, their vocations suddenly took on a greater purpose. Achieving technical miracles and overcoming bureaucratic battles, daunting setbacks and tragedies, the single "moonship" they built for the Apollo missions was effectively six individual spacecraft designed and built by five different companies. From the three separate rocket stages built by Boeing, North American Aviation and McDonnell Douglas, to the command, service and lunar modules, built by the Grumman Corporation and North American Aviation again, around five-and-a-half million parts were manufactured for each mission; often by a host of sub-contractors working for these main Apollo companies.

The near impossible task of managing this vast pyramid of people across America fell to the Apollo programme manager George Müller and, in a stroke of genius, he called upon the astronauts themselves for help; each national hero would make personal visits to the factories making all these parts. It was a crucial reminder to the workers that a single technical glitch could kill a man they had personally met. And it compelled each of them to devote their lives to Apollo for the best part of a decade.

During each flight, the colossal workforce would be on call - connected through their line managers - to a series of system support rooms in Houston which in turn fed their advice to one of 20 men in the main mission operations control room known to everyone as MOCR. Right at the top of the pyramid, inside this nerve centre, was one man in charge of each mission and his code name was Flight. For Apollo 11"s landing it was the turn of 36-year-old former fighter pilot, Gene Kranz.

An accomplishment of this immensity had transcended nationhood. Such global unity was something that no peacemaker, politician or prophet had ever quite achieved. But 400,000 engineers with a promise to keep to a president had done it and Nasa knew it. On the plaque fixed to the legs of their machine they had written the words: "We came in peace, for all mankind."Christopher Riley is the author of the new Haynes guide: Apollo 11 - an owner"s workshop manual. He curates the online Apollo film archive at Footagevault.com. His video commentaries about the Apollo mission are at theguardian.com/apollo11

There were dozens of other Apollo program subcontractors in the state. Many were small machine shops that turned out thousands of small parts ---- a few of which are still on the Moon.

The vast majority of the gear built for the Apollo mission never made it to the moon, according to Leighton Lee III, whose company, The Lee Co., of Westbrook, built thousands of tiny fluid flow management devices such as plugs and nozzles for the space program.

"The little subcontractors that built these parts always had the best, most-experienced machinist on the shop floor do the work," Lee said. "This was not easy. High-temperature metals are not easy to machine, and this was the age before there was such a thing as CAD/CAM."

He said much of Apollo was "first-of-a-kind" technology. A nautical engineer, for example, has some 8,000 years of shipbuilding tradition from which to draw.

The contracts for the parts were accompanied by the motivational statement: "For use in manned space flight. Materials, manufacturing and workmanship of highest quality standards are essential to astronaut safety."

"There were, perhaps, 100,000 contractors and subcontractors across the U.S. involved in the project," said Deborah Douglas, curator of the MIT Museum in Cambridge, Mass., which has an extensive collection of gear involved with the Apollo guidance systems.

"The parts needed to work not just because the astronauts" lives were at stake, but also because they were also demonstrating the nation"s technological prowess during the Cold War," she said.

A Lockheed Martin heritage company—the Lockheed Propulsion Company in Mentone, California—designed and built the solid propellant launch escape system (LES) and the pitch control motor for Apollo 11. The LES was designed to carry the crew safely away from the launch vehicle if an emergency occurred. When activated, the command module would separate from the service module and the LES would fire a solid fuel rocket connected to the top of the command module. A canard system would direct the command module away from the launch vehicle.

New England Wire Technologies was well-positioned to play a role in the Apollo program. Founded in 1898, just ten years after Edison’s invention of the light bulb, the company quickly became an important supplier to the 19th century’s budding electrical production and distribution industry. It grew further as the demand for motors and other electrical devices accelerated. And by the 1960s, technological advances had created demand for innumerable types of wire and cable which NEWT continued to fulfill.

However, the company’s contribution to space flight actually began much earlier than the Apollo program. The Mercury space program ran from 1958 to 1963. Its goal was to place an astronaut into earth orbit and return him safely. NASA then followed with the Gemini program, which ran from 1961 to 1963. It put two-man crews into orbit several times and perfected various maneuvers — extra-vehicular “space walks,” orbital adjustments and fine control protocols required to rendezvous and dock with other spacecraft. Gemini served as the testing and proving ground for subsequent Apollo missions. NEWT provided cable and wire to both programs and gained valuable insight into the diverse needs of spacecrafts.

The Apollo program ran from 1961 to 1972, with 15 flights taking wing under the Apollo banner. Apollo 1 was marked with tragedy when three astronauts died in a launchpad fire that caused NASA to undertake major redesign efforts. Flights 4 through 6 tested the Saturn launch vehicle that would carry men to the moon.

Apollo 7 through 10 were all manned flights, with Apollo 8 being the first to achieve a lunar orbit. Then, Apollo 11, 12 and 14 all landed on the moon, with only the aborted Apollo 13 mission failing to land.

The subsequent final flights under the Apollo program — 15, 16 and 17 — each put men on the moon for more extended periods. With modifications to the spacecraft needed to make room for lunar rovers, those vehicles carried men farther across the surface than any previous flights had allowed.

Note: NASA identified 15 flights as part of the overall Apollo spaceflight program. So, how did 16 and 17 come to be? The answer lies in the drastic, time-consuming and costly redesigns NASA worked through after the tragic Apollo 1 fire. The launches that had been planned as Apollo 2 and 3 were canceled and NASA resumed the series with Apollo 4.

The Space Transportation System (STS), commonly known as the space shuttle program, followed Apollo and continued until 2011. NEWT provided cable and wiring for the manual guidance system of the Columbia space shuttle, which began construction in 1975 and was first launched in 1982. The Columbia flew 27 missions over 22 years.

In 2001, space shuttle Endeavour delivered the robotic arm to the International Space Station (ISS). Known as Canadarm2 in honor of its Canadian manufacturers, the arm is almost 56 feet (17 m) long, weighs 3,300 pounds (1,497 kg), and is fabricated from 19 layers of high-strength carbon thermoplastic fibers. Modeled after the human arm, it can move in seven degrees of freedom, with three joints at the wrist, one joint at the elbow and three joints at the shoulder. Each end of the arm terminates in a 430 pound (195 kg) “hand” known as a “latching end effector.” Either end can attach to the ISS where it connects to fixtures located strategically around the periphery of the ISS. Those fixtures supply electrical power, data and video connections. NEWT supplied specialty wire and cable that allows Canadarm2 operators to manipulate loads up to quarter-million pounds (116,000 kg).

NASA, for instance, is focused on the “Moon to Mars” project that will place a Gateway mini-space station in orbit around the moon. NASA is evaluating ways that astronauts will be able to shuttle between Gateway and the moon on reusable landers — and, how to use Gateway as a way station so missions to the moon’s surface or even to Mars can rest, refuel and replace parts instead of relying on carrying everything from Earth.

Like Armstrong, Apollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objectsrecognizes the significance and power of artifacts. Tangible, real objects can connect the past to our present. Fifty years from the first lunar landing, the 50 objects in this book let us revisit a remarkable moment in American history, when grand ambitions overcame grand obstacles, and allow us to not only understand the moment anew but to make it part of our lives. They help tell the full story of spaceflight by revealing the tangle of technological, political, cultural, and social dimensions of the Apollo missions.

The material legacy of Apollo is immense. From capsules to space suits to the ephemera of life aboard a spacecraft, the Smithsonian Institution national collection comprises thousands of artifacts. This excerpt is from a carefully curated selection of 50 of these objects, which reveal how Project Apollo touched people’s lives, both within the space program and around the world.

American spacecraft were designed to land in the ocean. But slowing the capsule down proved challenging, even with highly engineered parachutes. The gaps in the ribbon, ring-sail main parachutes used by Apollo 16, offered greater stability at high speeds.

Published in time for the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing, this 104-page volume packed with photos includes the 25 most dramatic moments of the Apollo program, the extraordinary people who made it possible, and how a new generation of explorers plans to return to the moon.

In the cramped confines of the command module, Apollo 11’s astronauts frequently found it necessary to use whatever writing surface was available to take notes. Often, this meant they would turn to the walls of the craft itself. Command module pilot Michael Collins penned notes representing coordinates on a lunar surface map, relayed to him from Mission Control, as he attempted to locate his crewmates’ landing site from orbit. One later note was a tribute: Collins crawled back into Columbia while aboard the USS Hornet to inscribe a message (above) on the navigational system reading “Spacecraft 107—alias Apollo 11—alias Columbia. The best ship to come down the line. God Bless Her. Michael Collins, CMP.”

Boeing Aerospace designed the lunar roving vehicle (LRV) to extend the astronauts’ range; with the vehicle, crews could drive for 40 miles at a speed of up to 11 mph. Deployment of the vehicle took roughly 11 minutes, with an additional six minutes for navigational alignment and other checks. Apollo 15 astronaut Dave Scott compared it to deploying an “elaborate drawbridge.” Engineers constructed the LRV wheels from a hand-woven mesh made of zinc-coated piano wire, which is lighter and more durable than inflated rubber tires. Scott would later describe the LRV ride as “a cross between a bucking bronco and a small boat in a heavy swell.” The wheel pictured here is a spare from an LRV.

In July 1969, 94 percent of American households tuned their television sets to coverage of Apollo 11. Of these 53 million homes, the vast majority—including the sets at the White House—set their dials to watch news anchor Walter Cronkite on CBS. As the Saturn V rocket lifted off from Cape Canaveral, the usually composed Cronkite spontaneously exclaimed, “Go, baby, go!” Cronkite stayed on air for 27 of the 32 hours of continuous CBS coverage, detailing each stage of the Apollo 11 mission. Because much of the flight was out of sight of film cameras, Cronkite used a small-scale model to explain various stages of the mission.

When the Eagle lunar module touched down in the lunar soil, Cronkite could only cry, “Oh, boy!” before asking retired Apollo 7 astronaut Walter Schirra to say something because he could not. He quickly recovered, however, grasping the moment’s extraordinary significance: “Isn’t this something! 240,000 miles out there on the moon and we’re seeing this [on television].”

“Things which were fun a couple days ago, like shaving in weightlessness, now seem to be a nuisance,” lamented Michael Collins. Nine days into Apollo 11’s flight, inside a spacecraft that had become increasingly smelly and messy, lunar exploration had lost some of its luster.

The first human spaceflight missions were brief, lasting for hours instead of days. On these short flights, concerns about personal hygiene—such as brushing teeth and shaving—were irrelevant. But as NASA started planning for longer durations, the agency faced questions about how to maintain the astronauts’ health in space. Though shaving and other small rituals helped the astronauts maintain a sense of comfort and cleanliness en route to and from the moon, they also drew a sharp contrast with the counterculture movement of late 1960s America. This small razor and its accompanying shaving cream remind us how grooming sometimes represents more than just a style preference.

Michael Collins described simulation as the “heart and soul of NASA.” Simulator supervisors (affectionately known as “Sim Sups”) and their teams of instructors developed a clever series of challenging yet believable malfunctions to challenge Apollo flight crews to respond correctly in real-time situations. This highly realistic training was aimed at both the astronauts who would fly the missions and the flight controllers who would monitor spacecraft telemetry and assure that mission operations were conducted safely. Above is the control panel of the Apollo Mission Simulator, used to test the astronauts’ response to both routine and extreme events.

Apollo astronauts spent hundreds of hours training in these simulators in the months leading up to their missions. During each of the lunar missions, the astronauts inevitably compared the real experience of flying to the moon to the virtual experience that they had encountered during training. The phrase “just like the simulator” can be found in the transcripts from every Apollo mission.

The mission simulators helped save the flight crew of Apollo 13 after an explosion disabled all major spacecraft functions. On the ground, as teams of astronauts, simulator instructors, and flight controllers developed the intricate procedures to operate the crippled spacecraft, the Apollo Mission Simulators worked around the clock to validate each corrective action. These included the complex procedures to power up the dormant Apollo command module just prior to reentry into Earth’s atmosphere, a scenario that had never been contemplated by even the most devious simulation supervisors. The result was the safe return of Apollo 13 back to Earth, what some have called NASA’s “finest hour.”

Largely prepared by the astronauts themselves, checklists provided necessary step-by-step and switch-by-switch procedures. Detailed instructions also included reminders like when to wash their hands or that they should remove watches from pressure suits before they were stowed. Astronaut Michael Collins used the checklist above on board Apollo 11 in July 1969. Its 216 pages are divided into 15 “chapters” or sections: reference data, guidance and navigation computer, navigation, pre-thrust, thrusting, alignments, targeting, extending verbs (for display and keyboard), stabilization and control system general actions, systems management, lunar module interface, contingency extravehicular activity, lunar-orbit insertion aborts, flight emergency, and crew logs. A Velcro lining allowed it to be stuck in a number of locations around the spacecraft. The paper is fireproof, a provision put into place after the Apollo 1 tragedy.

Apollo 16 was the first to carry a small astronomical telescope. Called the Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph, it was the creation of George R. Carruthers and his team at the Naval Research Laboratory. Carruthers’ main goal was to get a first glimpse of what the universe looked like in the high-energy far ultraviolet region of the spectrum, which astronomers suspected held many answers to how stars and galaxies form. Astronauts on the moon could not see anything fainter than Earth in the sky because their eyes had to be protected by dense visors. So Carruthers designed the instrument to be easily handled. During three extravehicular activities, the astronauts photographed some 11 regions of the sky, including Earth. They captured over 500 stars, some nebulae and galaxies. The telescope still sits on the moon; only the film was returned to Earth. In 1981, two engineering models were transferred to the Museum; the one shown here was restored in 1992.

Adapted fromApollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objects, by Teasel Muir-Harmony (Smithsonian Institution and National Geographic, 2018). Printed with permission of the publisher.

Apollo 11 was a critical step forward for the nascent manned space flight program in America, a repurposing of nuclear weapons technology and a show of geopolitical dominance, a program rooted in the ineffable “right stuff” of the seemingly fearless naval test pilots who served as guinea pigs for the first flights into space.

In years to come, the first women and people of color to become NASA astronauts would be launched into space, the idea of private commercial space travel would become increasingly real, and one more step in the journey of Apollo 11 would be taken, again from the Pacific Northwest.

Blue Origin, one of a small number of private space-travel efforts, is the work of Amazon CEO and Seattle-area resident Jeff Bezos. Along with Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Blue Origin received no shortage of publicity since its founding in 2001. What has received less publicity is Bezos’ involvement with the artifacts left behind by Apollo 11, and the powerful Saturn V rockets that launched Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins and the astronauts who followed them into space.

Like Dr. James Joki’s backpacks and part of the lunar module, all abandoned on the moon during the journey of Apollo 11, the F-1 rocket engines that launched the spacecraft for NASA’s Apollo program were also dropped en route. They crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, where they fell 14,000 feet below the surface. They’d stay there for over 40 years.

But in 2010, Bezos, who has recounted watching the moon landing with wonder as a boy, quietly funded a recovery mission, and two expeditions led by David Concannon, a deep-water search and recovery expert, whose teams included a number of Seattleites. With limited geographic information provided by NASA about where the pieces might have ended up, the groups set to work, and ultimately retrieved several elements related to the F-1 rocket engines used at launch for Apollo 11, 12 and 16. The haul included the center F-1 engine from Apollo 11.

The remains of all three F-1s are now on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, and include an injector plate from Apollo 12, where, Huetter explains, the final combustion for liftoff would have entered the engine.

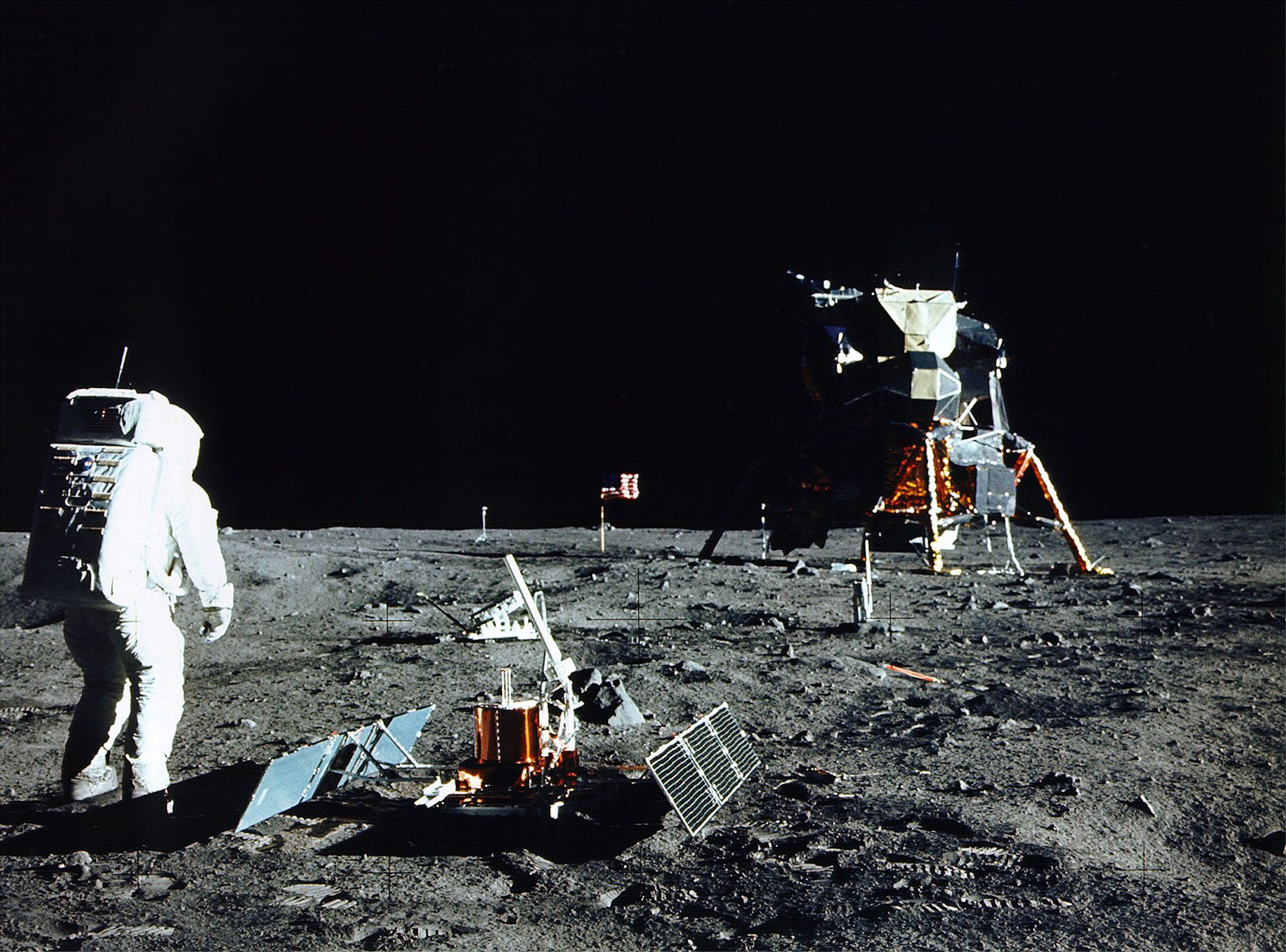

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module Eagle on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, and Armstrong became the first person to step onto the Moon"s surface six hours and 39 minutes later, on July 21 at 02:56 UTC. Aldrin joined him 19 minutes later, and they spent about two and a quarter hours together exploring the site they had named Tranquility Base upon landing. Armstrong and Aldrin collected 47.5 pounds (21.5 kg) of lunar material to bring back to Earth as pilot Michael Collins flew the Command Module Columbia in lunar orbit, and were on the Moon"s surface for 21 hours, 36 minutes before lifting off to rejoin Columbia.

Apollo 11 was launched by a Saturn V rocket from Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island, Florida, on July 16 at 13:32 UTC, and it was the fifth crewed mission of NASA"s Apollo program. The Apollo spacecraft had three parts: a command module (CM) with a cabin for the three astronauts, the only part that returned to Earth; a service module (SM), which supported the command module with propulsion, electrical power, oxygen, and water; and a lunar module (LM) that had two stages—a descent stage for landing on the Moon and an ascent stage to place the astronauts back into lunar orbit.

Since the Soviet Union had higher lift capacity launch vehicles, Kennedy chose, from among options presented by NASA, a challenge beyond the capacity of the existing generation of rocketry, so that the US and Soviet Union would be starting from a position of equality. A crewed mission to the Moon would serve this purpose.

In spite of that, the proposed program faced the opposition of many Americans and was dubbed a "moondoggle" by Norbert Wiener, a mathematician at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.Project Apollo.Nikita Khrushchev, the Premier of the Soviet Union in June 1961, he proposed making the Moon landing a joint project, but Khrushchev did not take up the offer.United Nations General Assembly on September 20, 1963.

An early and crucial decision was choosing lunar orbit rendezvous over both direct ascent and Earth orbit rendezvous. A space rendezvous is an orbital maneuver in which two spacecraft navigate through space and meet up. In July 1962 NASA head James Webb announced that lunar orbit rendezvous would be usedApollo spacecraft would have three major parts: a command module (CM) with a cabin for the three astronauts, and the only part that returned to Earth; a service module (SM), which supported the command module with propulsion, electrical power, oxygen, and water; and a lunar module (LM) that had two stages—a descent stage for landing on the Moon, and an ascent stage to place the astronauts back into lunar orbit.Saturn V rocket that was then under development.

Project Apollo was abruptly halted by the Apollo 1 fire on January 27, 1967, in which astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger B. Chaffee died, and the subsequent investigation.Apollo 7 evaluated the command module in Earth orbit,Apollo 8 tested it in lunar orbit.Apollo 9 put the lunar module through its paces in Earth orbit,Apollo 10 conducted a "dress rehearsal" in lunar orbit. By July 1969, all was in readiness for Apollo 11 to take the final step onto the Moon.

The Soviet Union appeared to be winning the Space Race by beating the US to firsts, but its early lead was overtaken by the US Gemini program and Soviet failure to develop the N1 launcher, which would have been comparable to the Saturn V.uncrewed probes. On July 13, three days before Apollo 11"s launch, the Soviet Union launched Luna 15, which reached lunar orbit before Apollo 11. During descent, a malfunction caused Luna 15 to crash in Mare Crisium about two hours before Armstrong and Aldrin took off from the Moon"s surface to begin their voyage home. The Nuffield Radio Astronomy Laboratories radio telescope in England recorded transmissions from Luna 15 during its descent, and these were released in July 2009 for the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11.

The initial crew assignment of Commander Neil Armstrong, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Jim Lovell, and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Buzz Aldrin on the backup crew for Apollo 9 was officially announced on November 20, 1967.Gemini 12. Due to design and manufacturing delays in the LM, Apollo 8 and Apollo 9 swapped prime and backup crews, and Armstrong"s crew became the backup for Apollo 8. Based on the normal crew rotation scheme, Armstrong was then expected to command Apollo 11.

There would be one change. Michael Collins, the CMP on the Apollo 8 crew, began experiencing trouble with his legs. Doctors diagnosed the problem as a bony growth between his fifth and sixth vertebrae, requiring surgery.Fred Haise filled in as backup LMP, and Aldrin as backup CMP for Apollo 8.STS-26 in 1988.

Deke Slayton gave Armstrong the option to replace Aldrin with Lovell, since some thought Aldrin was difficult to work with. Armstrong had no issues working with Aldrin but thought it over for a day before declining. He thought Lovell deserved to command his own mission (eventually Apollo 13).

The Apollo 11 prime crew had none of the close cheerful camaraderie characterized by that of Apollo 12. Instead, they forged an amiable working relationship. Armstrong in particular was notoriously aloof, but Collins, who considered himself a loner, confessed to rebuffing Aldrin"s attempts to create a more personal relationship.

The backup crew consisted of Lovell as Commander, William Anders as CMP, and Haise as LMP. Anders had flown with Lovell on Apollo 8.National Aeronautics and Space Council effective August 1969, and announced he would retire as an astronaut at that time. Ken Mattingly was moved from the support crew into parallel training with Anders as backup CMP in case Apollo 11 was delayed past its intended July launch date, at which point Anders would be unavailable.

By the normal crew rotation in place during Apollo, Lovell, Mattingly, and Haise were scheduled to fly on Apollo 14, but the three of them were bumped to Apollo 13: there was a crew issue for Apollo 13 as none of them except Edgar Mitchell flew in space again. George Mueller rejected the crew and this was the first time an Apollo crew was rejected. To give Shepard more training time, Lovell"s crew were bumped to Apollo 13. Mattingly would later be replaced by Jack Swigert as CMP on Apollo 13.

During Projects Mercury and Gemini, each mission had a prime and a backup crew. For Apollo, a third crew of astronauts was added, known as the support crew. The support crew maintained the flight plan, checklists and mission ground rules, and ensured the prime and backup crews were apprised of changes. They developed procedures, especially those for emergency situations, so these were ready for when the prime and backup crews came to train in the simulators, allowing them to concentrate on practicing and mastering them.Ronald Evans and Bill Pogue.

The capsule communicator (CAPCOM) was an astronaut at the Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas, who was the only person who communicated directly with the flight crew.Charles Duke, Ronald Evans, Bruce McCandless II, James Lovell, William Anders, Ken Mattingly, Fred Haise, Don L. Lind, Owen K. Garriott and Harrison Schmitt.

The Apollo 11 mission emblem was designed by Collins, who wanted a symbol for "peaceful lunar landing by the United States". At Lovell"s suggestion, he chose the bald eagle, the national bird of the United States, as the symbol. Tom Wilson, a simulator instructor, suggested an olive branch in its beak to represent their peaceful mission. Collins added a lunar background with the Earth in the distance. The sunlight in the image was coming from the wrong direction; the shadow should have been in the lower part of the Earth instead of the left. Aldrin, Armstrong and Collins decided the Eagle and the Moon would be in their natural colors, and decided on a blue and gold border. Armstrong was concerned that "eleven" would not be understood by non-English speakers, so they went with "Apollo 11",everyone who had worked toward a lunar landing".

After the crew of Apollo 10 named their spacecraft Charlie Brown and Snoopy, assistant manager for public affairs Julian Scheer wrote to George Low, the Manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office at the MSC, to suggest the Apollo 11 crew be less flippant in naming their craft. The name Snowcone was used for the CM and Haystack was used for the LM in both internal and external communications during early mission planning.

The astronauts had personal preference kits (PPKs), small bags containing personal items of significance they wanted to take with them on the mission.Columbia before launch, and two on Eagle.

Neil Armstrong"s LM PPK contained a piece of wood from the Wright brothers" 1903 "s left propeller and a piece of fabric from its wing,astronaut pin originally given to Slayton by the widows of the Apollo 1 crew. This pin had been intended to be flown on that mission and given to Slayton afterwards, but following the disastrous launch pad fire and subsequent funerals, the widows gave the pin to Slayton. Armstrong took it with him on Apollo 11.

NASA"s Apollo Site Selection Board announced five potential landing sites on February 8, 1968. These were the result of two years" worth of studies based on high-resolution photography of the lunar surface by the five uncrewed probes of the Lunar Orbiter program and information about surface conditions provided by the Surveyor program.

providing the Apollo spacecraft with a free-return trajectory, one that would allow it to coast around the Moon and safely return to Earth without requiring any engine firings should a problem arise on the way to the Moon;

During the first press conference after the Apollo 11 crew was announced, the first question was, "Which one of you gentlemen will be the first man to step onto the lunar surface?"

One of the first versions of the egress checklist had the lunar module pilot exit the spacecraft before the commander, which matched what had been done on Gemini missions,George Mueller told reporters he would be first as well. Aldrin heard that Armstrong would be the first because Armstrong was a civilian, which made Aldrin livid. Aldrin attempted to persuade other lunar module pilots he should be first, but they responded cynically about what they perceived as a lobbying campaign. Attempting to stem interdepartmental conflict, Slayton told Aldrin that Armstrong would be first since he was the commander. The decision was announced in a press conference on April 14, 1969.

For decades, Aldrin believed the final decision was largely driven by the lunar module"s hatch location. Because the astronauts had their spacesuits on and the spacecraft was so small, maneuvering to exit the spacecraft was difficult. The crew tried a simulation in which Aldrin left the spacecraft first, but he damaged the simulator while attempting to egress. While this was enough for mission planners to make their decision, Aldrin and Armstrong were left in the dark on the decision until late spring.

The ascent stage of LM-5 Eagle arrived at the Kennedy Space Center on January 8, 1969, followed by the descent stage four days later, and CSM-107 Columbia on January 23.Eagle and Apollo 10"s LM-4 Snoopy; Eagle had a VHF radio antenna to facilitate communication with the astronauts during their EVA on the lunar surface; a lighter ascent engine; more thermal protection on the landing gear; and a package of scientific experiments known as the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package (EASEP). The only change in the configuration of the command module was the removal of some insulation from the forward hatch.Operations and Checkout Building to the Vehicle Assembly Building on April 14.

The S-IVB third stage of Saturn V AS-506 had arrived on January 18, followed by the S-II second stage on February 6, S-IC first stage on February 20, and the Saturn V Instrument Unit on February 27. At 12:30 on May 20, the 5,443-tonne (5,357-long-ton; 6,000-short-ton) assembly departed the Vehicle Assembly Building atop the crawler-transporter, bound for Launch Pad 39A, part of Launch Complex 39, while Apollo 10 was still on its way to the Moon. A countdown test commenced on June 26, and concluded on July 2. The launch complex was floodlit on the night of July 15, when the crawler-transporter carried the mobile service structure back to its parking area.liquid hydrogen.ATOLL programming language.

The Apollo 11 Saturn V space vehicle lifts off with Astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. at 9:32 a.m. EDT July 16, 1969, from Kennedy Space Center"s Launch Complex 39A.

An estimated one million spectators watched the launch of Apollo 11 from the highways and beaches in the vicinity of the launch site. Dignitaries included the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General William Westmoreland, four cabinet members, 19 state governors, 40 mayors, 60 ambassadors and 200 congressmen. Vice President Spiro Agnew viewed the launch with former president Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife Lady Bird Johnson.Richard Nixon viewed the launch from his office in the White House with his NASA liaison officer, Apollo astronaut Frank Borman.

Saturn V AS-506 launched Apollo 11 on July 16, 1969, at 13:32:00 UTC (9:32:00 EDT).roll into its flight azimuth of 72.058°. Full shutdown of the first-stage engines occurred about 2 minutes and 42 seconds into the mission, followed by separation of the S-IC and ignition of the S-II engines. The second stage engines then cut off and separated at about 9 minutes and 8 seconds, allowing the first ignition of the S-IVB engine a few seconds later.

Apollo 11 entered a near-circular Earth orbit at an altitude of 100.4 nautical miles (185.9 km) by 98.9 nautical miles (183.2 km), twelve minutes into its flight. After one and a half orbits, a second ignition of the S-IVB engine pushed the spacecraft onto its trajectory toward the Moon with the trans-lunar injection (TLI) burn at 16:22:13 UTC. About 30 minutes later, with Collins in the left seat and at the controls, the transposition, docking, and extraction maneuver was performed. This involved separating Columbia from the spent S-IVB stage, turning around, and docking with Eagle still attached to the stage. After the LM was extracted, the combined spacecraft headed for the Moon, while the rocket stage flew on a trajectory past the Moon.slingshot effect from passing around the Moon threw it into an orbit around the Sun.

On July 19 at 17:21:50 UTC, Apollo 11 passed behind the Moon and fired its service propulsion engine to enter lunar orbit.Sabine D. The site was selected in part because it had been characterized as relatively flat and smooth by the automated Ranger 8 and Surveyor 5 landers and the Lunar Orbiter mapping spacecraft, and because it was unlikely to present major landing or EVA challenges.

Five minutes into the descent burn, and 6,000 feet (1,800 m) above the surface of the Moon, the LM guidance computer (LGC) distracted the crew with the first of several unexpected 1201 and 1202 program alarms. Inside Mission Control Center, computer engineer Jack Garman told Guidance Officer Steve Bales it was safe to continue the descent, and this was relayed to the crew. The program alarms indicated "executive overflows", meaning the guidance computer could not complete all its tasks in real-time and had to postpone some of them.Margaret Hamilton, the Director of Apollo Flight Computer Programming at the MIT Charles Stark Draper Laboratory later recalled:

To blame the computer for the Apollo 11 problems is like blaming the person who spots a fire and calls the fire department. Actually, the computer was programmed to do more than recognize error conditions. A complete set of recovery programs was incorporated into the software. The software"s action, in this case, was to eliminate lower priority tasks and re-establish the more important ones. The computer, rather than almost forcing an abort, prevented an abort. If the computer hadn"t recognized this problem and taken recovery action, I doubt if Apollo 11 would have been the successful Moon landing it was.

During the mission, the cause was diagnosed as the rendezvous radar switch being in the wrong position, causing the computer to process data from both the rendezvous and landing radars at the same time.Don Eyles concluded in a 2005 Guidance and Control Conference paper that the problem was due to a hardware design bug previously seen during testing of the first uncrewed LM in Apollo 5. Having the rendezvous radar on (so it was warmed up in case of an emergency landing abort) should have been irrelevant to the computer, but an electrical phasing mismatch between two parts of the rendezvous radar system could cause the stationary antenna to appear to the computer as dithering back and forth between two positions, depending upon how the hardware randomly powered up. The extra spurious cycle stealing, as the rendezvous radar updated an involuntary counter, caused the computer alarms.

Eagle landed at 20:17:40 UTC on Sunday July 20 with 216 pounds (98 kg) of usable fuel remaining. Information available to the crew and mission controllers during the landing showed the LM had enough fuel for another 25 seconds of powered flight before an abort without touchdown would have become unsafe,

He then took communion privately. At this time NASA was still fighting a lawsuit brought by atheist Madalyn Murray O"Hair (who had objected to the Apollo 8 crew reading from the Book of Genesis) demanding that their astronauts refrain from broadcasting religious activities while in space. For this reason, Aldrin chose to refrain from directly mentioning taking communion on the Moon. Aldrin was an elder at the Webster Presbyterian Church, and his communion kit was prepared by the pastor of the church, Dean Woodruff. Webster Presbyterian possesses the chalice used on the Moon and commemorates the event each year on the Sunday closest to July 20.

Apollo 11 used slow-scan television (TV) incompatible with broadcast TV, so it was displayed on a special monitor and a conventional TV camera viewed this monitor (thus, a broadcast of a broadcast), significantly reducing the quality of the picture.Goldstone in the United States, but with better fidelity by Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station near Canberra in Australia. Minutes later the feed was switched to the more sensitive Parkes radio telescope in Australia.recordings of the original slow scan source transmission from the lunar surface were likely destroyed during routine magnetic tape re-use at NASA.

Armstrong intended to say "That"s one small step for a man", but the word "a" is not audible in the transmission, and thus was not initially reported by most observers of the live broadcast. When later asked about his quote, Armstrong said he believed he said "for a man", and subsequent printed versions of the quote included the "a" in square brackets. One explanation for the absence may be that his accent caused him to slur the words "for a" together; another is the intermittent nature of the audio and video links to Earth, partly because of storms near Parkes Observatory. A more recent digital analysis of the tape claims to reveal the "a" may have been spoken but obscured by static. Other analysis points to the claims of static and slurring as "face-saving fabrication", and that Armstrong himself later admitted to misspeaking the line.

About seven minutes after stepping onto the Moon"s surface, Armstrong collected a contingency soil sample using a sample bag on a stick. He then folded the bag and tucked it into a pocket on his right thigh. This was to guarantee there would be some lunar soil brought back in case an emergency required the astronauts to abandon the EVA and return to the LM.Hasselblad camera that could be operated hand held or mounted on Armstrong"s Apollo space suit.

They deployed the EASEP, which included a passive seismic experiment package used to measure moonquakes and a retroreflector array used for the lunar laser ranging experiment.Little West Crater while Aldrin collected two core samples. He used the geologist"s hammer to pound in the tubes—the only time the hammer was used on Apollo 11—but was unable to penetrate more than 6 inches (15 cm) deep. The astronauts then collected rock samples using scoops and tongs on extension handles. Many of the surface activities took longer than expected, so they had to stop documenting sample collection halfway through the allotted 34 minutes. Aldrin shoveled 6 kilograms (13 lb) of soil into the box of rocks in order to pack them in tightly.basalt and breccia.armalcolite, tranquillityite, and pyroxferroite. Armalcolite was named after Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins. All have subsequently been found on Earth.

Mission Control used a coded phrase to warn Armstrong his metabolic rates were high, and that he should slow down. He was moving rapidly from task to task as time ran out. As metabolic rates remained generally lower than expected for both astronauts throughout the walk, Mission Control granted the astronauts a 15-minute extension.

Aldrin entered Eagle first. With some difficulty the astronauts lifted film and two sample boxes containing 21.55 kilograms (47.5 lb) of lunar surface material to the LM hatch using a flat cable pulley device called the Lunar Equipment Conveyor (LEC). This proved to be an inefficient tool, and later missions preferred to carry equipment and samples up to the LM by hand.life support, the explorers lightened the ascent stage for the return to lunar orbit by tossing out their PLSS backpacks, lunar overshoes, an empty Hasselblad camera, and other equipment. The hatch was closed again at 05:11:13. They then pressurized the LM and settled down to sleep.

Presidential speech writer William Safire had prepared an In Event of Moon Disaster announcement for Nixon to read in the event the Apollo 11 astronauts were stranded on the Moon.White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman, in which Safire suggested a protocol the administration might follow in reaction to such a disaster.burial at sea. The last line of the prepared text contained an allusion to Rupert Brooke"s World War I poem "The Soldier".

After more than 21+1⁄2 hours on the lunar surface, in addition to the scientific instruments, the astronauts left behind: an Apollo 1 mission patch in memory of astronauts Roger Chaffee, Gus Grissom, and Edward White, who died when their command module caught fire during a test in January 1967; two memorial medals of Soviet cosmonauts Vladimir Komarov and Yuri Gagarin, who died in 1967 and 1968 respectively; a memorial bag containing a gold replica of an olive branch as a traditional symbol of peace; and a silicon message disk carrying the goodwill statements by Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon along with messages from leaders of 73 countries around the world.

One of Collins" first tasks was to identify the lunar module on the ground. To give Collins an idea where to look, Mission Control radioed that they believed the lunar module landed about 4 miles (6.4 km) off target. Each time he passed over the suspected lunar landing site, he tried in vain to find the module. On his first orbits on the back side of the Moon, Collins performed maintenance activities such as dumping excess water produced by the fuel cells and preparing the cabin for Armstrong and Aldrin to return.

Just before he reached the dark side on the third orbit, Mission Control informed Collins there was a problem with the temperature of the coolant. If it became too cold, parts of Columbia might freeze. Mission Control advised him to assume manual control and implement Environmental Control System Malfunction Procedure 17. Instead, Collins flicked the switch on the system from automatic to manual and back to automatic again, and carried on with normal housekeeping chores, while keeping an eye on the temperature. When Columbia came back around to the near side of the Moon again, he was able to report that the problem had been resolved. For the next couple of orbits, he described his time on the back side of the Moon as "relaxing". After Aldrin and Armstrong completed their EVA, Collins slept so he could be rested for the rendezvous. While the flight plan called for Eagle to meet up with Columbia, Collins was prepared for a contingency in which he would fly Columbia down to meet Eagle.

Eagle rendezvoused with Columbia at 21:24 UTC on July 21, and the two docked at 21:35. Eagle"s ascent stage was jettisoned into lunar orbit at 23:41.Apollo 12 flight, it was noted that Eagle was still likely to be orbiting the Moon. Later NASA reports mentioned that Eagle"s orbit had decayed, resulting in it impacting in an "uncertain location" on the lunar surface.

Aldrin added:This has been far more than three men on a mission to the Moon; more, still, than the efforts of a government and industry team; more, even, than the efforts of one nation. We feel that this stands as a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all mankind to explore the unknown ... Personally, in reflecting on the events of the past several days, a verse from Psalms comes to mind. "When I consider the heavens, the work of Thy fingers, the Moon and the stars, which Thou hast ordained; What is man that Thou art mindful of him?"

Armstrong concluded:The responsibility for this flight lies first with history and with the giants of science who have preceded this effort; next with the American people, who have, through their will, indicated their desire; next with four administrations and their Congresses, for implementing that will; and then, with the agency and industry teams that built our spacecraft, the Saturn, the Columbia, the Eagle, and the little EMU, the spacesuit and backpack that was our small spacecraft out on the lunar surface. We would like to give special thanks to all those Americans who built the spacecraft; who did the construction, design, the tests, and put their hearts and all their abilities into those craft. To those people tonight, we give a special thank you, and to all the other people that are listening and watching tonight, God bless you. Good night from Apollo 11.

The aircraft carrier USS Hornet, under the command of Captain Carl J. Seiberlich,LPH USS Princeton, which had recovered Apollo 10 on May 26. Hornet was then at her home port of Long Beach, California.Pearl Harbor on July 5, Hornet embarked the Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King helicopters of HS-4, a unit which specialized in recovery of Apollo spacecraft, specialized divers of UDT Detachment Apollo, a 35-man NASA recovery team, and about 120 media representatives. To make room, most of Hornet"s air wing was left behind in Long Beach. Special recovery equipment was also loaded, including a boilerplate command module used for training.

On July 12, with Apollo 11 still on the launch pad, Hornet departed Pearl Harbor for the recovery area in the central Pacific,Secretary of State William P. Rogers and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger flew to Johnston Atoll on Air Force One, then to the command ship USS Arlington in Marine One. After a night on board, they would fly to Hornet in Marine One for a few hours of ceremonies. On arrival aboard Hornet, the party was greeted by the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Command (CINCPAC), Admiral John S. McCain Jr., and NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine, who flew to Hornet from Pago Pago in one of Hornet"s carrier onboard delivery aircraft.

Weather satellites were not yet common, but US Air Force Captain Hank Brandli had access to top-secret spy satellite images. He realized that a storm front was headed for the Apollo recovery area. Poor visibility which could make locating the capsule difficult, and strong upper-level winds which "would have ripped their parachutes to shreds" according to Brandli, posed a serious threat to the safety of the mission.Fleet Weather Center at Pearl Harbor, who had the required security clearance. On their recommendation, Rear Admiral Donald C. Davis, commander of Manned Spaceflight Recovery Forces, Pacific, advised NASA to change the recovery area, each man risking his career. A new location was selected 215 nautical miles (398 km) northeast.

This altered the flight plan. A different sequence of computer programs was used, one never before attempted. In a conventional entry, trajectory event P64 was

8613371530291

8613371530291