mission parts michales made in china

Michaels is the largest arts and crafts retail chain in North America. In addition to our retail outlets, The Michaels Companies also own multiple brands that allow us to collectively provide arts, crafts, framing, floral, home décor, and seasonal merchandise to hobbyists and do-it-yourself home decorators. We believe anyone can make, and we’re on a mission to inspire and encourage everyone to unleash his or her inner maker.

The history of the missions of the Jesuits in China is part of the history of relations between China and the Western world. The missionary efforts and other work of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, between the 16th and 17th century played a significant role in continuing the transmission of knowledge, science, and culture between China and the West, and influenced Christian culture in Chinese society today.

The first attempt by the Jesuits to reach China was made in 1552 by St. Francis Xavier, Navarrese priest and missionary and founding member of the Society of Jesus. Xavier never reached the mainland, dying after only a year on the Chinese island of Shangchuan. Three decades later, in 1582, Jesuits once again initiated mission work in China, led by several figures including the Italian Matteo Ricci, introducing Western science, mathematics, astronomy, and visual arts to the Chinese imperial court, and carrying on significant inter-cultural and philosophical dialogue with Chinese scholars, particularly with representatives of Confucianism. At the time of their peak influence, members of the Jesuit delegation were considered some of the emperor"s most valued and trusted advisors, holding prestigious posts in the imperial government.

According to research by David E. Mungello, from 1552 (i.e., the death of St. Francis Xavier) to 1800, a total of 920 Jesuits participated in the China mission, of whom 314 were Portuguese, and 130 were French.

Fairly soon after the establishment of the direct European maritime contact with China (1513) and the creation of the Society of Jesus (1540), at least some Chinese became involved with the Jesuit effort. As early as 1546, two Chinese boys enrolled in the Jesuits" St. Paul"s College in Goa, the capital of Portuguese India. One of these two Christian Chinese, known as Antonio, accompanied St. Francis Xavier, a co-founder of the Society of Jesus, when he decided to start missionary work in China. However, Xavier failed to find a way to enter the Chinese mainland, and died in 1552 on Shangchuan island off the coast of Guangdong,

A few years after Xavier"s death, the Portuguese were allowed to establish Macau, a semi-permanent settlement on the mainland which was about 100 km closer to the Pearl River Delta than Shangchuan Island. A number of Jesuits visited the place (as well as the main Chinese port in the region, Guangzhou) on occasion, and in 1563 the Order permanently established its settlement in the small Portuguese colony. However, the early Macau Jesuits did not learn Chinese, and their missionary work could reach only the very small number of Chinese people in Macau who spoke Portuguese.

A new regional manager ("Visitor") of the order, Alessandro Valignano, on his visit to Macau in 1578–1579 realized that Jesuits weren"t going to get far in China without a sound grounding in the language and culture of the country. He founded St. Paul Jesuit College (Macau) and requested the Order"s superiors in Goa to send a suitably talented person to Macau to start the study of Chinese. Accordingly, in 1579 the Italian Michele Ruggieri (1543–1607) was sent to Macau, and in 1582 he was joined at his task by another Italian, Matteo Ricci (1552–1610).Isabel Reigota in Macau, Mercia Roiz in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Candida Xu in China, all donated significant amounts towards establishing missions in China as well as to other Asian states from China.

Just as Ricci spent his life in China, others of his followers did the same. This level of commitment was necessitated by logistical reasons: Travel from Europe to China took many months, and sometimes years; and learning the country"s language and culture was even more time-consuming. When a Jesuit from China did travel back to Europe, he typically did it as a representative ("procurator") of the China Mission, entrusted with the task of recruiting more Jesuit priests to come to China, ensuring continued support for the Mission from the Church"s central authorities, and creating favorable publicity for the Mission and its policies by publishing both scholarly and popular literature about China and Jesuits.Chongzhen Emperor was nearly converted to Christianity and broke his idols.

In 1685, the French king Louis XIV sent a mission of five Jesuit "mathematicians" to China in an attempt to break the Portuguese predominance: Jean de Fontaney (1643–1710), Joachim Bouvet (1656–1730), Jean-François Gerbillon (1654–1707), Louis Le Comte (1655–1728) and Claude de Visdelou (1656–1737).

Johann Adam Schall (1591–1666), a German Jesuit missionary to China, organized successful missionary work and became the trusted counselor of the Shunzhi Emperor of the Qing Dynasty. He was created a mandarin and held an important post in connection with the mathematical school, contributing to astronomical studies and the development of the Chinese calendar. Thanks to Schall, the motions of both the sun and moon began to be calculated with sinusoids in the 1645 Shíxiàn calendar (時憲書, Book of the Conformity of Time). His position enabled him to procure from the emperor permission for the Jesuits to build churches and to preach throughout the country. The Shunzhi Emperor, however, died in 1661, and Schall"s circumstances at once changed. He was imprisoned and condemned to slow slicing death. After an earthquake and the dowager"s objection the sentence was not carried out, but he died after his release owing to the privations he had endured. A collection of his manuscripts remains and was deposited in the Vatican Library. After he and Ferdinand Verbiest won the tests against Chinese and Islamic calendar scholars, the court adapted the western calendar only.

To disseminate information about devotional, educational and scientific subjects, several missions in China established printing presses: for example, the Imprimerie de la Mission Catholique (Sienhsien), established in 1874.

At first the focal point of dissension was the Jesuit Ricci"s contention that the ceremonial rites of Confucianism and ancestor veneration were primarily social and political in nature and could be practiced by converts. The Dominicans, however, charged that the practices were idolatrous, meaning that all acts of respect to the sage and one"s ancestors were nothing less than the worship of demons. A Dominican carried the case to Rome where it dragged on and on, largely because no one in the Vatican knew Chinese culture sufficiently to provide the pope with a ruling. Naturally, the Jesuits appealed to the Chinese emperor, who endorsed Ricci"s position. Understandably, the emperor was confused as to why missionaries were attacking missionaries in his capital and asking him to choose one side over the other, when he might very well have simply ordered the expulsion of all of them.

The timely discovery of the Xi"an Stele in 1623 enabled the Jesuits to strengthen their position with the court by answering an objection the Chinese often expressed – that Christianity was a new religion. The Jesuits could now point to concrete evidence that a thousand years earlier the Christian gospel had been proclaimed in China; it was not a new but an old faith. The emperor then decided to expel all missionaries who failed to support Ricci"s position.

Among the last Jesuits to work at the Chinese court were Louis Antoine de Poirot (1735–1813) and Giuseppe Panzi (1734-before 1812) who worked for the Qianlong Emperor as painters and translators.Paris Foreign Missions Society.

Mungello (2005), p. 37. Since Italians, Spaniards, Germans, Belgians, and Poles participated in missions too, the total of 920 probably only counts European Jesuits, and does not include Chinese members of the Society of Jesus.

Egor Fedorovich Timkovskiĭ; Hannibal Evans Lloyd; Julius Heinrich Klaproth; Julius von Klaproth (1827). Travels of the Russian mission through Mongolia to China: and residence in Pekin, in the years 1820-1821. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. pp. 29–.

Swerts, Lorry, Mon Van Genechten, Koen De Ridder. (2002). Mon Van Genechten (1903–1974): Flemish Missionary and Chinese Painter : Inculturation of Chinese Christian Art. Leuven University Press. ISBN 90-5867-222-0 ISBN 9789058672223.

Born in a rural part of the Russian Empire (now Belarus), to a Jewish family, Borodin joined the General Jewish Labour Bund at age sixteen, and then the Bolsheviks in 1903. After being arrested for participating in revolutionary activities, Borodin fled to America, attended Valparaiso University, started a family, and later established an English school for Russian Jewish immigrants in Chicago. Upon the success of the October Revolution in 1917, Borodin returned to Russia, and served in various capacities in the new Soviet government. From 1919, he served as an agent of the Comintern, travelling to various countries to spread the Bolshevik revolutionary cause. In 1921, Borodin arrived in Turkey to help the Turkish National Movement in the War of Independence against Britain. He was arrested and detained by Britain for half a year due to his activities in Turkey. In 1923, Vladimir Lenin picked Borodin to lead a Comintern mission to China, where he was tasked with aiding Sun Yat-sen and his Kuomintang. Following Sun"s death, Borodin assisted in the planning of the Northern Expedition, and later became an integral backer of the KMT leftist government in Wuhan.

Borodin later returned to Britain under the alias "George Brown", where he was tasked with ascertaining the cause of the revolution"s failure there, and reorganising the British Communist Party.Glasgow, ostensibly for breaking immigration regulations, though his political mission was known.Guangzhou, the seat of Sun Yat-sen"s revolutionary government, on 6 October.

Greeted upon his arrival in Guangzhou by Eugene Chen, with whom he later became close, Borodin found that Sun"s government was teetering on the brink of collapse. Faced with rampant corruption, anti-Bolshevik feeling in parts of the KMT, and the ever-present threat of the warlords and the Beijing-based Beiyang government, Borodin was tasked with reforming the Kuomintang into a potent revolutionary force.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24168738/1428277847.jpg)

In the early 16th century, the Portuguese were about as much of a threat to the great Ming empire as gnats to an elephant. And at first, the Portuguese did little to challenge the Chinese system of trade. They sought relations with China very much like the standard seaborne barbarians who had been floating to Guangzhou for centuries. The 1517 mission carried Tomé Pires, a former pharmacist appointed by the Portuguese king as the country’s first official envoy to the Ming court. The Portuguese intended to become a vassal state of the Ming Son of Heaven and participate in tribute and trade like other barbarians, to gain access to lucrative Chinese goods. Their goal, in other words, was to join the Chinese world, not subvert it.

The Portuguese were dazzled by what they found in Guangzhou. Its incredible wealth far surpassed anything back home. One contemporary Portuguese account records their wonderment at a lavish ceremony to welcome a governor returning to the city. “The ramparts were covered in silken banners, while on the towers reared flagstaffs from which also hung silken flags, so huge that they could be used as sails,” it reads. “Such is the wealth of that country, such is its vast supply of silk, that they squander gold leaf and silk on these flags where we use cheap colors and coarse linen cloth.”

Andrade had arrived at an auspicious moment, when the emperor, Zhengde, was less hostile to foreigners and international exchanges than most of his Ming predecessors. Chinese officials in Guangzhou agreed to accept Pires and his retinue, to await permission to visit the emperor. When Andrade departed in 1518, he left relations with China on a solid footing. “Andrade had arranged matters in the city of [Guangzhou] and the country of China so smoothly that, after he had left, commerce between Portuguese and Chinese was conducted in peace and safety, and men made great profits,” one Portuguese scribe recorded. Not for long.

The reports of this atrocious behavior sent to Beijing doomed the already-troubled Pires mission. The Portuguese ambassador had made his way to the capital, where he awaited an audience with the emperor. The climate was somewhat hostile. Chinese officials sent memorials to the court condemning the Portuguese for their ill treatment of the king of Malacca and advocating that the emperor reject the Pires embassy. Making matters worse, Pires handed the court a letter from the Portuguese sovereign, King Manuel I, that the Chinese found impertinent. It was composed “in the manner he customarily adopted towards pagan princes,” according to a Portuguese description.

The death of the emperor in 1521 signaled the end of the mission. Pires was hustled out of Beijing the next day and sent back to Guangzhou. There he was forced to write to King Manuel of the emperor’s demand that the Portuguese restore the sultan of Malacca to his rightful throne, and Pires was held hostage for compliance. He would never leave China. Sometimes kept in harsh conditions and fettered, he died there in 1524.

The situation got uglier still when a new flotilla of Portuguese came to trade shortly after the emperor’s death. When news of his demise trickled in to Guangzhou, local officials ordered the Portuguese and all other foreign traders to depart. But the ornery Portuguese, already conducting business, refused. The Chinese assembled a sizable fleet and attacked the outnumbered Portuguese, sinking one of their vessels and taking prisoners. On two other occasions, Portuguese trading ships and Chinese war junks came to blows. Then, in 1522, another Portuguese squadron showed up off the Chinese coast with a commission to forge peaceful relations with the Ming. They blithely sailed into a Chinese onslaught that sank two of their three ships. The unfortunate Portuguese captured in these engagements endured a horrible end. “Twenty-three individuals were each hacked to pieces, losing their heads, legs and arms,” one surviving eyewitness recounted. “Their genitals were stuffed in their mouths, and the trunk of each body was wrapped around the belly in two chunks.”

From their inception, relations with the West ran by different rules. The Chinese, though, retained the upper hand. The Portuguese had some nifty military technology, most of all their highly effective cannon, which the Chinese duly noticed. But the handful of ships they were capable of deploying on the Chinese coast could not possibly challenge Ming supremacy. (In fact, the expert seafarers of Portugal learned a thing or two about shipbuilding from the Chinese, including the practice of waterproofing wooden hulls with a coating of bitumen.) And just in case these folangji got out of line, a wall and a gate were constructed across the narrow point of the Macau peninsula in 1573, and the Portuguese were forbidden to cross it. Significantly, little farmland was enclosed on the Macau side of the wall, which left the Portuguese dependent on the Chinese for food. The Ming could simply lock the gate and starve these barbarians into submission. Macau existed only at China’s pleasure.

In 2017, in the middle of its three-year ramping up of military assistance and economic investment, China established its first overseas military base in Djibouti, on the coast of the Horn of Africa. Djibouti, situated at the strategic entrance to the Red Sea corridor across from Yemen, also hosts military installations belonging to the United States, Germany, Spain, Italy, France, the UK, Japan, and Saudi Arabia. Consonant with China’s multilateral messaging – China provides more troops to UN Security Council (UNSC) peacekeeping missions than all the other UNSC permanent members combined – Beijing was able to portray its unilateral military presence as part of the international effort to combat piracy and protect global trade passing through the Suez Canal. China has participated in the Shared Awareness and De-Confliction interface, which coordinates the respective anti-piracy efforts of the US-led multinational Combined Taskforce 151 and EU NAVFOR in waters off the Horn of Africa. Nonetheless, China’s establishment of its Djibouti base, with a dock reportedly capable of accommodating aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines, is also in keeping with its journey towards consolidating a continent-wide security presence.

On the evening of January 2, a Chinese lander named for an ancient moon goddess touched down on the lunar far side, where no human or robot has ever ventured before. China"s Chang"e-4 mission launched toward the moon on December 7 and entered orbit around our cosmic companion on December 12. Now, the spacecraft has alighted onto the lunar surface.

The Chang"e-4 probe is the latest mission sent to the moon by CNSA, the Chinese space agency. The first two lunar missions were orbiters, and the third was a lander-rover combo that successfully landed on the near side of the moon in 2013. Chang"e-4 consists of a lander and a rover, as well as a relay satellite, and its goal is to set down gently on the lunar far side. (See stunning pictures from the Chang"e-3 mission.)

The Chang"e-4 mission has gotten around this problem with a relay satellite. In May 2018, CNSA launched a satellite called Queqiao into orbit around L2, a neutral point beyond the moon where the gravity of Earth and the moon cancel out the centripetal force of an object stationed there, effectively allowing it to park in place. Since Queqiao always has good sight lines to both Earth and the lunar far side, it will bridge the gap between mission control and the Chang"e-4 lander.

Many of the instruments aboard Chang"e-4 are replicas of ones that flew on Chang"e-3, the mission"s predecessor. These hand-me-downs include several cameras, including the one that Chang"e-3 used to take awe-inspiring panoramas of the lunar surface. Chang"e-4 also comes equipped with radar that can penetrate the moon"s surface.

Unlike Chang"e-3, Chang"e-4 is carrying a "lunar biosphere" experiment containing plant seeds and silkworm eggs, as well as a low-frequency radio spectrometer that will let researchers study the sun"s high-energy atmosphere from afar. This instrument has an extra trick: By pairing it with an instrument on board Queqiao, Chinese researchers can use the two as a radio telescope. The moon"s far side is ideal for radio astronomy, since the moon blocks noise from Earth"s ionosphere and human radio transmissions.

Not all of Chang"e-4"s instruments are Chinese. The mission"s scientists teamed up with German researchers to install a particle detector on the lander, and Swedish researchers put an ion detector on the rover. The radio-telescope instrument on Queqiao is a joint Dutch-Chinese effort.

There are models for countries cooperating in space even when tensions persist back on Earth. During the Cold War, the U.S. worked with the U.S.S.R. for projects such as the Apollo-Soyuz mission. Some observers, such as Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins, even advocated for the U.S. and the Soviet Union to embark on a joint Mars mission. (Read Collins"s plan in the November 1988 issue of National Geographicmagazine.)

China has big plans for its lunar exploration program. Its next mission, Chang"e-5, will attempt to land on the moon"s surface and return samples to Earth. If China is successful, it would be just the third country to send stuff back from the moon, and the second country to do so with robots. While details are slim, Chinese researchers outlining the country"s post-2020 moon plans have also discussed sending humans to the moon and building a base there.

“If at some point we can marshal the world"s resources to do these things, we"re going to be a lot better off,” says Kurt Klaus, the commercial lead for the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group, which supports NASA"s moon missions. “But how far away we are from that, I don"t know.”

The Biden administration would have liked a slightly more even balance between the competitive, collaborative, and adversarial parts of the US-China relationship, but that’s not where Xi wants to take it.

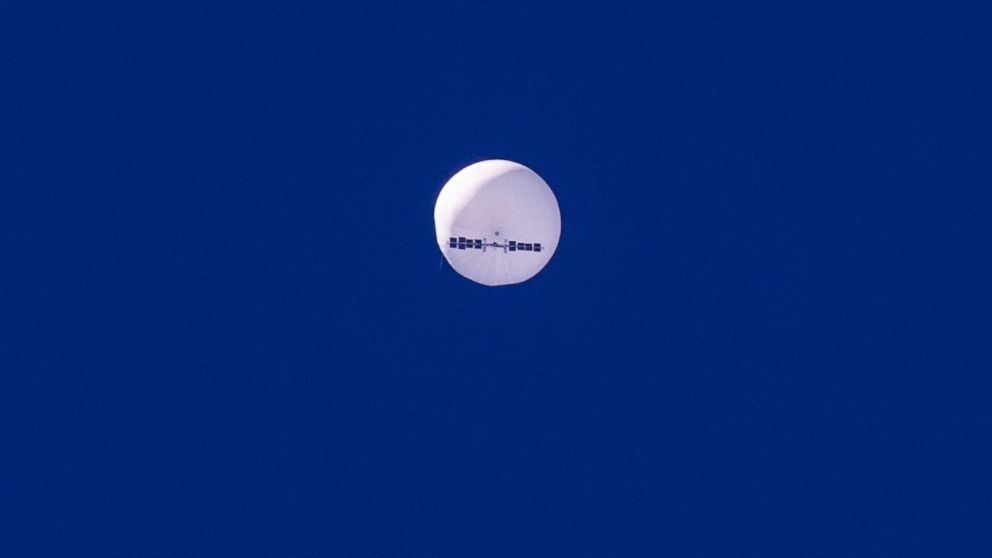

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., was more positive: “Thank you to the men and women of the United States military who were responsible for completing the mission to shoot down the Chinese surveillance balloon. The Biden Administration did the right thing in bringing it down.”

By the following year things had taken a more sinister turn. Red Guards laid siege to the Soviet, French and Indonesian embassies, torched the Mongolian ambassador’s car and hung a sign outside the British mission that read: “Crush British Imperialism!” One night, in late August, diplomats were forced to flee from the British embassy as it was ransacked and burned. Outside protesters chanted: “Kill! Kill!”.

While much has been made of the tense March 18 exchange between American and Chinese diplomats in Anchorage, Alaska, one area became an unlikely candidate for cooperation: outer space. During a press conference after the meeting, Jake Sullivan, the U.S. National Security Advisor, pointed out that the Perseverance rover that recently landed on Mars “wasn’t just an American project. It had technology from multiple countries from Europe and other parts of the world.” China’s top diplomat, Yang Jiechi, seized the opportunity to say that, “China would welcome it if there is a will to carry out similar cooperation from the United States with us.”

Planned or not, Yang’s comment gave voice to one very smart way two geopolitical rivals sharing the same planet could work together despite their growing tensions. Space exploration has long been used to foster deep cooperation, even between adversaries. During the height of the Cold War, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. jointly undertook the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz mission, which both served as a means of political rapprochement and opened the possibility of cooperation in other areas. Those links endured. After the Soviet Union collapsed, Russia was invited to partner in the construction of the International Space Station (ISS). It was a multi-layered act that went beyond simple generosity; the more work former Soviet scientists had to do designing and building the ISS, the less likely they’d be to sell their expertise to other countries.

The U.S. has extensively shared the entire ISS program for decades with the fourteen partner nations, including Russia. If there ever were secrets there, they are secrets no more. In fact, Russia and the U.S. as partners saved the day between 2011, after the space shuttles were grounded, and 2021, when the U.S. regained the ability to transport astronauts to space. During that decade, Russia’s Soyuz spacecraft served as the only way to get crews to and from the station. At the same time, uncrewed American resupply ships similarly helped keep the ISS viable when the Russian Soyuz fleet was grounded following mishaps. China has developed and proven a very successful human spaceflight program; adding their launch and spacecraft capability to the partnership would strengthen the overall mission.

In order for China and the U.S. to work together in space, some things would have to change. First, the Wolf Amendment would have to be repealed—nothing meaningful can happen until that goes. Cooperation might then begin in lower profile areas such as sharing remote sensing data and reducing orbital debris. The United States and Europe have led the way with Landsat and Copernicus satellite programs providing free images of Earth that can be used to understand changes to our environment. The Chinese have yet to create a similar data share program for their Earth imaging systems—but they should. The United States and China could also discuss joint efforts to reduce the belt of space junk that circles the planet and threatens everyone’s satellites. Most importantly, cooperation could extend to joint human spaceflight missions; the US could invite China to conduct a crewed visit to the ISS, or to join in the human exploration of the Moon, targeted to happen in this decade and which both nations are now working on separately; the goal would be a joint Moon base rather than a space race.

Will Marshall is CEO of Planet which operates 200 satellites that image the entire Earth landmass on a daily basis, and he formerly worked at NASA on lunar missions and space debris.

London Missionary Society establishes Hong Kong College of Medicine, which later became the University of Hong Kong. First western institute of higher education in Hong Kong

Winfried Baumgart devotes this study to defining the idea of European Imperialism. He split this broad concept into three separate and more manageable subcategories. First, he explains the political atmosphere of mid-ninteenth century Europe. He qualifies various preconditions that made eastern expansion possible. He highlights the significance of early trading port, naval developments, missionary activities, exploration, and technological advancements. Second he approaches the topic of imperialism from a nationalistic perspective. He explains social conception of nationalism and the “white man’s burden” to not only expand into foreign lands but also to culturally educate the natives. Furthermore, Baumgart also explains the competitive nature of nationalism amongst fellow European imperialist nations. The importance of political and economic dominance becomes a major issue between imperialist nations. His final subcategory is the economic theory behind this expansionist enterprise. In this part of the book, Baumgart discusses the application of capitalist and mercantilist economic theories in foreign markets. He analyses the economic policy of Protectionism which is significant for understanding the imperialist initiatives for the Opium War. This book serves as a strong introduction to the broad idea of Imperialism.

6.1 Lord Maccartney’s Commission from Henry Dundas, 1792-This document was the a letter from Henry Dundas, a representative from the East India Company, written the Lord Macartney, a British Diplomat in China. This letter represents the early attitude of Europeans towards the Qing empire. The tone of this letter shows shows British dignity but also respects the authority of the Chinese. This attitude would change significantly after industrialization and and the Opium Wars.

The Opium War of 1839 was the first large scale military conflicts between the Qing Empire and western imperial powers. With the official prohibition of opium in 1836 in China, the Qing government launched a campaign to confiscate all foreign imported opium in Canton. In 1839, commissioner Lin Zexu seized over a million kilograms of opium and burned them. The British Empire responded by sending in the military and initiating the first Opium War. The result of this war not only lead to China’s lost of Hong Kong Island, but also revealed the military weakness of the Qing government. Up to this point western imperialist powers have been wary of the Qing Empire, but after this conflict, China begins to experience a series of disadvantageous economic pressures form Britain and other European empires. In Peter Fey’s The Opium War,the author explains the economic intentions of the British Empire in China before 1839 and after 1842. He highlights the significance of the first Opium War, its legacy of further western aggression, and the subsequent Chinese movements of military industrialization and self strengthening.

The following is a translated letter from Commissioner Lin Zexu to Queen Victoria on the eve of the first Opium War in 1839. Although this letter never reached Queen Victoria, it nevertheless represented the views of Lin regarding both the Opium Trade in Canton and the broader idea of the free market. Lin approaches the topic of restricting opium in a respectful but assertive tone. He also addresses the problem of imperialism. “We [The Chinese] find your country [Britain] is sixty or seventy thousand li [about 4800 miles] from China Yet there are barbanan ships that strive to come here for trade for the purpose of making a great profit The wealth of China is used to profit the barbarians.” Though Lin does not fully understand the western concept of Imperialism, he is one of the earliest Chinese officials to recognize the “Barbarians” as a future threat to both Qing authority and Chinese society.

9.8 Chinese Anti-Foreignism, 1892-This document was a pamphlet circulating in Canton. In the late nineteenth century, Canton was under the influence of Britain. Along with the merchants and imperialists came a new wave of religious advocates and missionaries. This pamphlet ridicules Christianity as religion and spreads disturbing and untrue stereotypes about white foreigners. This document serves as a Chinese counterpart to the British perspective of “native barbarian” in China, India and Africa.

At the Beijing Xiangshan Forum on October 24, 2018, Major General Ding Xiangrong, Deputy Director of the General Office of China’s Central Military Commission, gave a major speech in which he defined China’s military goals to “narrow the gap between the Chinese military and global advanced powers” by taking advantage of the “ongoing military revolution . . . centered on information technology and intelligent technology.” Chinese military leaders increasingly refer to intelligent or “intelligentized” (智能化) military technology as their confident expectation for the future basis of warfare. Use of the term “intelligentized” is meant to signify a new stage of military technology beyond the current stage based on information technology.

Beyond using AI for autonomous military robotics, China is also interested in AI capabilities for military command decisionmaking. Zeng Yi expressed some remarkable opinions on this subject, stating that today “mechanized equipment is just like the hand of the human body. In future intelligent wars, AI systems will be just like the brain of the human body.” Zeng also said that “Intelligence supremacy will be the core of future warfare” and that “AI may completely change the current command structure, which is dominated by humans” to one that is dominated by an “AI cluster.” Zeng did not elaborate on his claims, but they are consistent with broader thinking in Chinese military circles. Several months after AlphaGo’s momentous March 2016 victory over Lee Sedol, a publication by China’s Central Military Commission Joint Operations Command Center argued that AlphaGo’s victory “demonstrated the enormous potential of artificial intelligence in combat command, program deduction, and decisionmaking.”

8613371530291

8613371530291