mud pump discharge formula price

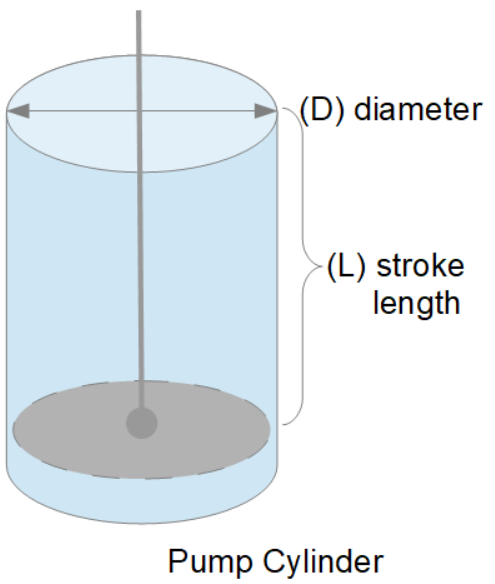

Rig pump output, normally in volume per stroke, of mud pumps on the rig is one of important figures that we really need to know because we will use pump out put figures to calculate many parameters such as bottom up strokes, wash out depth, tracking drilling fluid, etc. In this post, you will learn how to calculate pump out put for triplex pump and duplex pump in bothOilfield and Metric Unit.

Pump Output per Stroke (PO): The calculator returns the pump output per stroke in barrels (bbl). However this can be automatically converted to other volume units (e.g. gallons or liters) via the pull-down menu.

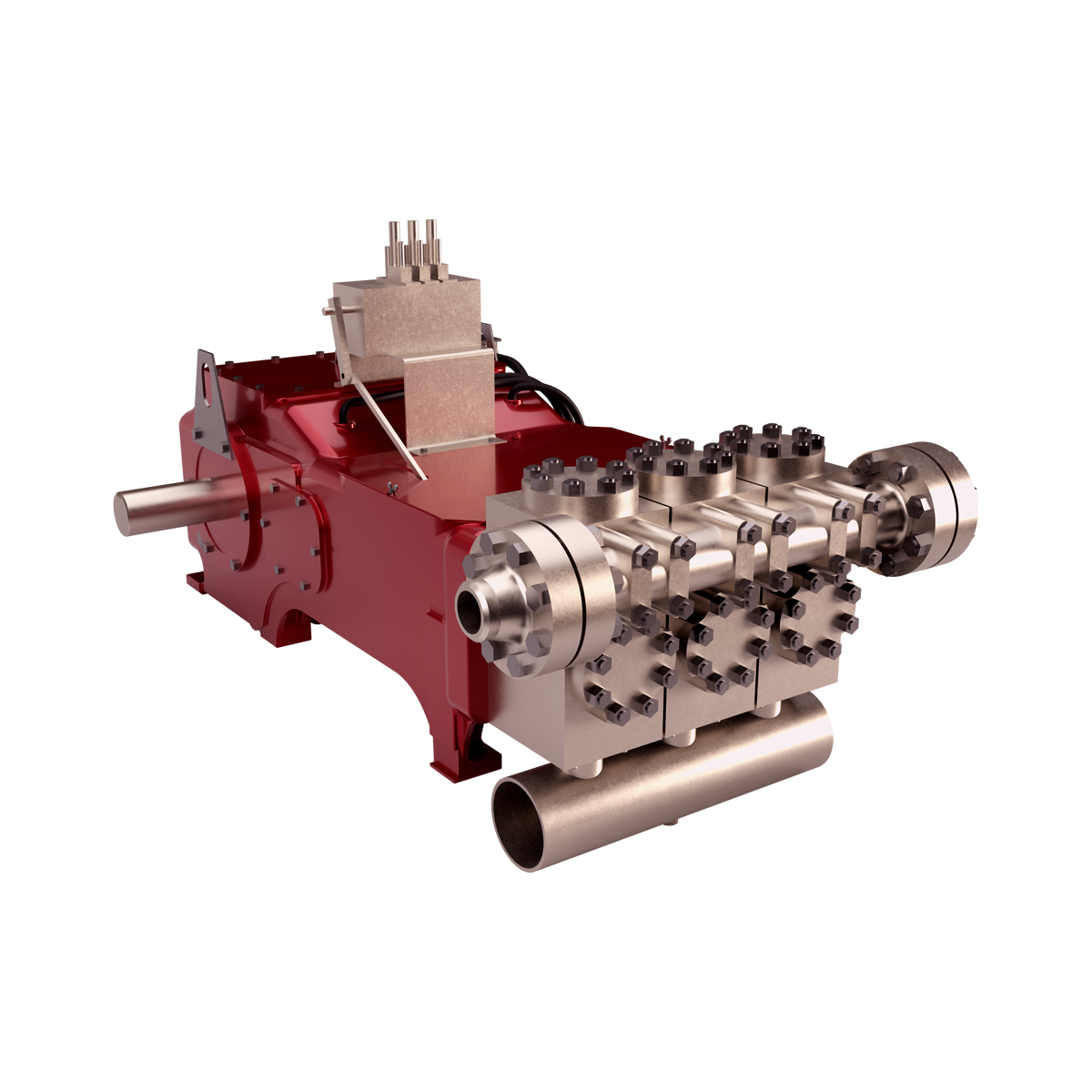

A triplex mud (or slush) pump has three horizontal plungers (cylinders) driven off of one crankshaft. Triplex mud pumps are often used for oil drilling.

The NOV 12-P-160 Mud Pumps includes (3) Three New National 12-P-160 Triplex Mud Pumps 1600 HP, 7-1/4″ bore x 12″ stroke, single acting. 5000 PSI fluid ends. 1600 HP Bare Mud Pumps are currently configured for Offshore Service. The NOV 12-P-160 Mud Pumps are located in Houston and ready to be unitized for service.

Forged Steel crankshaft, Individual forged steel two piece interchangeable standard modules, 6-1/2” mission fluid king liners, Standard polyurethane valves and seats, Two piece fast change piston rods, Supreme pistons, Metal to metal liner retention, Clamp type liner and piston rod connections, Fast change valve covers standard, Piston liner lubricant spray system, Liner spray pump, Power end lube system with filter. Mounted on Integral two runner skid, Suction Manifold with vertical suction stabilizer, Suction line pressure relief valve, set for 70 PSI

Includes: motor supports, motor frame, tensioning screws, 2 V-belt guards, 2 pump Sheaves, 2 motor sheaves, banded V-belts, Holes to be drilled to accept EDM D79 Or GE-752 Traction Motors

National Oilwell Varco (NOV) is an American multinational corporation based in Houston, Texas. It is a leading worldwide provider of equipment and components used in oil and gas drilling and production operations, oilfield services, and supply chain integration services to the upstream oil and gas industry. The company conducts operations in more than 600 locations across six continents, operating through three reporting segments: Rig Technologies, Wellbore Technologies, and Completion & Production Solutions. National Oilwell’s two main predecessors, Oilwell Supply and National Supply, were founded in 1862 and 1893, respectively. These two companies manufactured and distributed pumps and derricks.

Since the NOV A1700-PT Triplex Mud Pump was built approximately 60 years ago, the industry has widely accepted the three cylinder or triplex style pump. Triplex mud pumps are manufactured worldwide, and many companies have emulated the original design and developed an improved form of the triplex pump in the past decade.

NOV A1700-PT Triplex Mud Pumps have many advantages they weight 30% less than a duplex of equal horsepower or kilowatts. The lighter weight parts are easier to handle and therefore easier to maintain. The other advantages include;They cost less to operate

One of the more important advantages of triplex over duplex pumps, is that they can move large volumes of mud at the higher pressure is required for modern deep hole drilling.

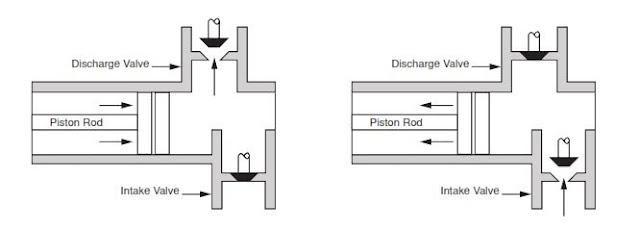

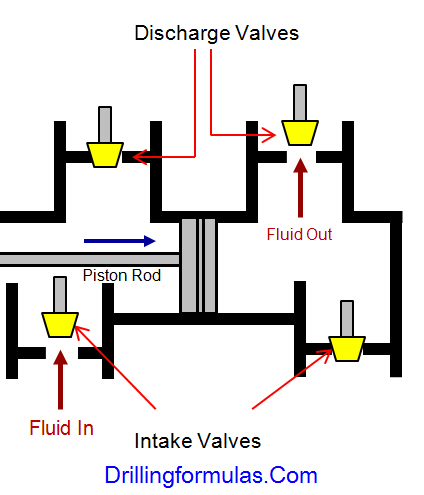

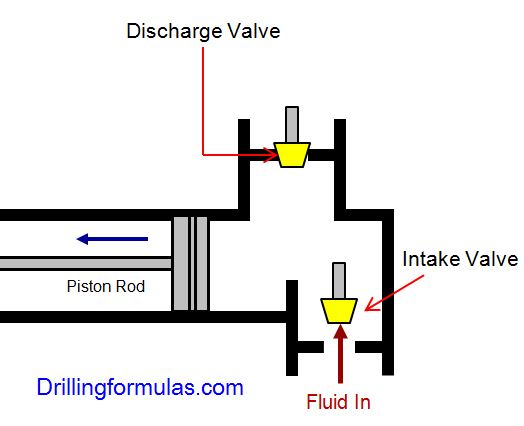

NOV A1700-PT Triplex Mud Pump is gradually phasing out duplex units. In a triplex pump, the pistons discharge mud only when they move forward in the liner. Then, when they moved back they draw in mud on the same side of the piston. Because of this, they are also called “single acting.” Single acting triplex pumps, pump mud at a relatively high speeds. NOV A1700-PT Triplex Mud Pump has three pistons each moving in its own liner. It also has three intake valves and three discharge valves. It also has a pulsation dampener in the discharge line.

GDEP is the original creator of the drilling pump and continues to set the standard for durable, high-quality drilling pumps that can withstand the world’s toughest drilling environments. Starting with our PZ7 and rounding out with the market"s most popular pump, the PZ1600, our PZ Series of pumps are the perfect choice for today"s high-pressure drilling applications.

Pumps tend to be one of the biggest energy consumers in industrial operations. Pump motors, specifically, require a lot of energy. For instance, a 2500 HP triplex pump used for frac jobs can consume almost 2000 kW of power, meaning a full day of fracking can cost several thousand dollars in energy costs alone!

So, naturally, operators should want to maximize energy efficiency to get the most for their money. Even a 1% improvement in efficiency can decrease annual pumping costs by tens of thousands of dollars. The payoff is worth the effort. And if you want to remotely control your pumps, you want to keep efficiency in mind.

In this post, we’ll point you in the right direction and discuss all things related to pump efficiency. We’ll conclude with several tips for how you can maintain pumping efficiency and keep your energy costs down as much as possible.

In simple terms, pump efficiency refers to the ratio of power out to power in. It’s the mechanical power input at the pump shaft, measured in horsepower (HP), compared to the hydraulic power of the liquid output, also measured in HP. For instance, if a pump requires 1000 HP to operate and produces 800 HP of hydraulic power, it would have an efficiency of 80%.

Remember: pumps have to be driven by something, i.e., an electric or diesel motor. True pump system efficiency needs to factor in the efficiency of both the motor AND the pump.

Consequently, we need to think about how electrical power (when using electric motors) or heat power (when using combustion engines) converts into liquid power to really understand pump efficiency.

Good pump efficiency depends, of course, on pump type and size. High-quality pumps that are well-maintained can achieve efficiencies of 90% or higher, while smaller pumps tend to be less efficient. In general, if you take good care of your pumps, you should be able to achieve 70-90% pump efficiency.

Now that we have a better understanding of the pump efficiency metric, let’s talk about how to calculate it. The mechanical power of the pump, or the input power, is a property of the pump itself and will be documented during the pump setup. The output power, or hydraulic power, is calculated as the liquid flow rate multiplied by the "total head" of the system.

IMPORTANT: to calculate true head, you also need to factor in the work the pump does to move fluid from the source. For example, if the source water is below the pump, you need to account for the extra work the pump puts in to draw source water upwards.

*Note - this calculation assumes the pump inlet is not pressurized and that friction losses are minimal. If the pump experiences a non-zero suction pressure, or if there is significant friction caused by the distance or material of the pipe, these should be factored in as well.

You"ll notice that the elevation head is minimal compared to the discharge pressure, and has minimal effect on the efficiency of the pump. As the elevation change increases or the discharge pressure decreases, however, elevation change will have a greater impact on total head.

Obviously, that’s a fair amount of math to get at the pump efficiency, considering all of the units conversions that need to be done. To avoid doing these calculations manually, feel free to use our simple pump efficiency calculator.

Our calculations use static variables (pump-rated horsepower and water source elevation) and dynamic variables (discharge flow and pressure). To determine pump efficiency, we need to measure the static variables only once, unless they change.

If you want to measure the true efficiency of your pump, taking energy consumption into account, you could add an electrical meter. Your meter should consist of a current transducer and voltage monitor (if using DC) for electrical motors or a fuel gauge for combustion. This would give you a true understanding of how pump efficiency affects energy consumption, and ultimately your bank account.

Up until this point, we’ve covered the ins and outs of how to determine pump efficiency. We’re now ready for the exciting stuff - how to improve pump efficiency!

One of the easiest ways to improve pump efficiency is to actually monitor pumps for signs of efficiency loss! If you monitor flow rate and discharge (output power) along with motor current or fuel consumption, you’ll notice efficiency losses as soon as they occur. Simply having pump efficiency information on hand empowers you to take action.

Another way to increase efficiency is to keep pumps well-maintained. Efficiency losses mostly come from mechanical defects in pumps, e.g., friction, leakages, and component failures. You can mitigate these issues through regular maintenance that keeps parts in working order and reveals impending failures. Of course, if you are continuously monitoring your pumps for efficiency drops, you’ll know exactly when maintenance is due.

You can also improve pump efficiency by keeping pumps lubricated at all times. Lubrication is the enemy of friction, which is the enemy of efficiency (“the enemy of my enemy is my friend…”).

A fourth way to enhance pump efficiency is to ensure your pumps and piping are sized properly for your infrastructure. Although we’re bringing this up last, it’s really the first step in any pumping operation. If your pumps and piping don’t match, no amount of lubricant or maintenance will help.

In this post, we’ve given you the full rundown when it comes to calculating and improving pump efficiency. You can now calculate, measure, and improve pump efficiency, potentially saving your business thousands of dollars annually on energy costs.

For those just getting started with pump optimization, we offer purpose-built, prepackaged solutions that will have you monitoring pump efficiency in minutes, even in hazardous environments.

When two (or more) pumps are arranged in serial their resulting pump performance curve is obtained by adding theirheads at the same flow rate as indicated in the figure below.

Centrifugal pumps in series are used to overcome larger system head loss than one pump can handle alone. for two identical pumps in series the head will be twice the head of a single pump at the same flow rate - as indicated with point 2.

With a constant flowrate the combined head moves from 1 to 2 - BUTin practice the combined head and flow rate moves along the system curve to point 3. point 3 is where the system operates with both pumps running

When two or more pumps are arranged in parallel their resulting performance curve is obtained by adding the pumps flow rates at the same head as indicated in the figure below.

Centrifugal pumps in parallel are used to overcome larger volume flows than one pump can handle alone. for two identical pumps in parallel and the head kept constant - the flow rate doubles compared to a single pump as indicated with point 2

Note! In practice the combined head and volume flow moves along the system curve as indicated from 1 to 3. point 3 is where the system operates with both pumps running

In practice, if one of the pumps in parallel or series stops, the operation point moves along the system resistance curve from point 3 to point 1 - the head and flow rate are decreased.

The “pond” is actually a man made dam which covers an area of about 40ha and has rockfill embankments of up to 53m high along the southern side that forms the impoundment. It initially constructed in 1959 to act as a tailings pond to take the bauxite residue (red mud) from the Ewarton Plant situated about 5km away and 300m lower. The red mud was pumped as a slurry comprising about 20% solids to the pond over a period of about 32 years up to 1991 when the pond was replaced by the Charlemount Mud Stacking and Drying Facility. During this period the pond embankments (referred to as dams), were raised up to 7 times providing a final crest elevation of 472m. The pond was however never filled to its final design capacity and the mud beach level remained at about 469m and the central area about 458m leaving a concave depression which held about 1.4mil m3 of water with elevated pH and some caustic content.

The remediation plan for the pond includes the removal of the ponded water and then the regrading of the mud surface to be free draining so that it can be stabilised and vegetated. About 500,000 m3 of mud will need to be moved over a distance of up to 1km in order to create the required profile. Due to the very soft nature of the surface muds (shear strength of less than 3kPa) its bearing capacity is less than 20kPa hence it is not accessible using even modified earthworks equipment. In addition, the muds are thyrotrophic and under any vibration or shear loading, rapidly liquefy resulting in significant reduction in shear strength and loss of bearing capacity. Using conventional earthmoving equipment would therefore require extensive “floating” haul roads with a high risk of machinery getting stuck or entire plant loss and risk to personnel. It was therefore decided to investigate the possibility of pumping the in-situ red mud.

A mud pumping trial was undertaken to assess the feasibility of using this technique to do the bulk mud moving. Pumping red mud is not unusual and the muds were initially pumped up to Mt Rosser Pond. However, the muds are usually pumped at a solids content of 30% or less. Once deposited, they can take years to reconsolidate and firm up sufficiently to allow access for light earthworks and agricultural plant.

In addition to the mud pumping, the trial included infilling three small scale geotubes to assess their performance as these may be needed as part of the regrading works.

The main aim of the pump trial was to determine if the muds could be pumped in their insitu state, and if not, what amount of water is required and how the variations in water content affect pump rates.

The mud pumping trial was undertaken using a 4” EDDY Pump. This pump was recommended due to its ability to handle variable solids and robust operating mechanism. The pump unit incorporated a hydraulic drive and cutter head. The unit was mounted onto the boom of a JCB 220 excavator which also supplied the hydraulic feed to power the pump for the required range of 30-40 GPM at 3,500 to 4,000 psi (2428MPa). The cutter head was powered by a standalone hydraulic power unit capable of providing the required 30gpm at 200psi (1.9 l/s at 13.8MPa). If mounted on a 30-ton excavator with a System 14 hydraulic system and dual auxiliary feeds to the boom, all necessary hydraulic power for the pump and cutter head can be supplied by the excavator. This equipment was however not available at the time in Jamaica.

In addition to the pump mounted on the excavator a Long Reach excavator (CAT 325) was used to move muds towards the cutter head but also to loosen up the muds and mix in additional water to facilitate pumping. Water was added by pumping it directly from the pond using a 3” diesel water pump.

Prior to pumping the muds, the mud pump would operate in recirculation mode in order to prime the pump. When in recirculation (re-circ) mode, the material pumped would be diverted to a short discharge pipe mounted on the pump directed back parallel to the cutter head. This action would help agitate and stir the muds.

A geotechnical soils investigation was undertaken on the muds within Mt Rosser pond in 2004. It showed the material to be predominantly clayey silt with approximately 13% sand, 29% clay and 58% silt using conventional sieve analysis and hydrometer. Atterberg limits indicate that the material is an intermediate to high plasticity clay. The muds do however vary across the lake and also vertically. This is mainly as a consequence of the deposition process and discharge location. Close to the discharge location the courser materials would settle out first and the finer materials would disperse furthest and to the opposite end of the pond. The results are presented in figure 4.1.

Earlier this year, additional mud samples were tested as it was evident that standard soil mechanics tests did not provide an accurate assessment of this fine material. This was particularly evident in tests done with dry sieving which shows the material as well-graded sand (see results for samples 5300, 5301, 5302 on figure 4.2). When dispersed in water, even with an agent, the ‘yield-pseudo-plastic’ rheology of the muds appeared to affect the hydrometer results with large variations between tests (see results of samples PFT4&5 taken during mud pumping trials on figure 4.2).

The additional testing comprised of undertaking gradings using a Laser Particle Analyzer. The results indicated that the muds are predominantly Silt although the silt % varied from 30% to 80% with the material being either more sandy or more clayey (up to 15% clay). See results of samples ending in “L” on figure 4.2 below.

Moisture content tests on the muds taken from within the mud pond but below the ponded water ranged from 100% to 150% (50% to 40% solids). The muds at the pump test location were 137% (42% solids).

Shear strength was generally very low ranging from 1kPa to 6kPa increasing with depth. Dynamic probes previously undertaken indicated that the muds are “very soft” to 5m increasing in strength slightly to “soft” at a depth of 9m after which they increase to firm becoming stiff.

The pH of the muds ranged from 10.3 to 11.7, (ave 11.2). Previous testing indicated that the surface muds have the lower pH although once through the crust, the pH tends to be higher. When doing the trials, the muds up to a depth of about 2.5m was intermixed, hence any stratification in pH could not be determined.

Initially, pumping was problematic mainly due to the excavator being underpowered. This was diagnosed as a hydraulic pump problem and the excavator was replaced. The cutter head (which also acts to protect the intake) tended to blind with mud (Photo 5.1) and was also not providing enough agitation to liquefy the muds. This was partly resolved by adding “stirrers” (2 steel loops welded either side) to the rotating cutter head and also a “comb” (Photo 5.2) to keep the gaps within the cutter head open.

Mud pumping rates varied from 21 l/s to 52 l/s (332 – 824gpm) and it was clearly visible that the more liquid the muds were the higher the pump rate was. Samples were taken at different discharge rates and moisture content and percent solids determined by laboratory testing. The results are plotted in Figure 5.1 and although scattered, do give an indication of the effects of solids content on flow rates. The natural moisture content of the muds (insitu) at the test location was 137%, or 42% solids. This is shown in Figure 5.1 as a vertical line. Pumping muds close to the percent solids was achieved although flow rates were low.

As mentioned previously, the long reach excavator was used to loosen up the muds. Water was pumped from the pond using a 3” pump into the excavation and the long reach would then work the muds to mix the water in. The mud pump would then be used in recirculation mode to further mix the muds into a more consistent state. Even with this mixing and agitation, the water tended to concentrate on the surface. This aided the initial process of priming the pump and once primed thicker muds at 1m to 2m below the surface could be pumped. However, it was found that the deeper muds tended to be lumpy and this would significantly reduce or stop the flow requiring the pump to be lifted into thinner muds or having to go back into re-circ mode or having to fully re-prime. The pump discharge was therefore very inconsistent as the suction intake position constantly needed adjustment in an attempt to get adequate discharge but also pump the thickest muds possible.

Discharge of the pumped muds was through 30m of flexible hose then 60m of 4” HDPE pipe which had an internal diameter of about 87mm (3.5”). The muds were discharged onto the original mud beach which lies at a gradient of about 9%. On deposition the muds slowly flowed down gradient. At times the flow would stop and the muds would build up then flow again in a wave motion. The natural angle of repose would therefore be a few degrees less than this – probably 5% to 6%.

Although the muds have very low shear strength, and on agitation liquefy, the sides of the excavation had sufficient strength to stand about 2m near vertical. Even overnight, there was limited slumping and the bank could be undermined by about 0.5m with the cutter head/agitator before collapsing.

On termination of pumping, in order to flush the pipeline, thin watery muds were pumped until the line was clear. A “T” valve system was then used to connect the 3” water pump line and this was then used to flush the pipe with water.

Three geotubes (1m x 6m) were filled with red muds pumped using the 4” Eddy pump. Fill rates were about 30 to 40l/s although it was difficult to assess as the flow and mud consistence was not visible.

Tube 1 was filled initially with more runny mud and then thicker muds as the pump operator got a better feel for conditions. The tube was filled until firm. The second tube was filled with thicker muds and filling continued until the tube was taut. These two tubes were positioned on the sloping beach in order to form a small “U” impoundment area that would later be filled with pumped muds. Although the area was prepared, the sloping ground caused the first tube to rotate through about 20 degrees. The tube was staked and the downslope side backfilled. A more defined bed was created for the second tube and the same rotational issue was limited. The two filled tubes with the ponded mud are shown in Photos 5.7 and 5.8. Other than a small leak at the contact between the two geotubes, the ponding of the muds was successful.

The third tube was positioned on level ground. It was filled with medium runny (but consistent thickness) muds and was filled until the tube was taut.

In all three cases, there was very little mud loss or seepage from the tubes. When stood on, some red water would squeeze out around the pressure area. Once filled taut, the entire bag would have small red water droplets form on the outside (visible in Photo 5.11) , but the seepage was in general nominal.

The tubes have been monitored and the most recent photo’s taken on 10 October 2011 (6 weeks after filling) show how the tubes have reduced in volume due to the dewatering of the contained muds. Volume loss is estimated to be around 30%. The anticipated moisture content would therefore be about 90% and the solids around 53%.

The muds pumped into the trial pond behind the geotubes were medium thick to thick, probably in the order of 37 – 40% solids. After 6 weeks the mud has not only firmed-up but had dried out significantly with wide and deep surface cracks as are evident in Photo 5.14 and 5.15.

The muds can be pumped at close to their insitu moisture content and most likely at their in-situ moisture content if they were agitated more and the pipeline system was designed to reduce friction losses.

Be able to access the mud surface and move around efficiently and safely. The suggestion is to have the pump mounted on a pontoon that is positioned using high strength rope (dynema) or steel cable. The pump system should be remotely controlled as this would limit regular movement of personnel on the muds.

Have sufficient power and volume capacity to pump the muds at close to or at in-situ moisture content and discharge them about 1000m through a flexible pipeline.

It was also evident from the trials that the muds do not slump and flow readily. It will therefore be necessary to have an amphibious excavator to loosen up the muds in the area around the pump head. This weakened and more liquid mud would also aid the movement of the pump pontoon. To also limit the amount of movement the pontoon will need to do, the amphibious excavator could also move muds towards the pump location.

Using the capacity of the 4” mud pump, mud moving would take about 1.5 to 2 years, the pump will however need to be more suited to the task. A target period of 1 year however seems reasonable. However, prior to this, equipment will need to be procured and imported into Jamaica. The 6 and 10 inch Excavator Dredge Pump Attachments are also being considered as an option for higher GMP and a more aggressive completion timeline. A preliminary programme is as follows:

Whether you operate an industrial pump or looking to purchase the right pumps in India for your needs, the flow rate of the system is a crucial parameter. In this guide, Sintech, the no.1 industrial

Flow rate is the amount of fluid that the pump can transport within a given time. Knowing the flow rate of your pump can help you achieve two key things:

You can figure out if your system is working efficiently. If you know the expected flow rate and the current flow rate, then you can identify if your system is underperforming. This helps you make the right action to improve the pump’s performance.

Before you approach multistage centrifugal pump manufacturers in India for your purchase needs, having an idea of the desired flow rate will help you plan the system design perfectly. If you calculate the required flow rate wrong, then you would install an oversized/undersized pump, which is not a good investment in the long run. So, you need to have a clear idea of the desired flow rate before ordering the best pumps in India from your preferred manufacturer.

You need to calculate three factors before ordering the right pumps:The type of fluid you need to pump – is it viscous or clear? What’s the temperature of the pumped fluid? Etc.

The volume of fluid that needs to be transported in a specific timeAll these three factors will vary based on your industrial needs. The volume of fluid that you want to transport determines the flow rate of the pump. The type of fluid and the distance transported both play a huge role in impacting the flow rate that you can achieve. Hence, all these three factors play a crucial role in determining the size and type of pump needed.

We highly recommend that you contact a pump sizing expert to help you decide the correct equipment to buy. At Sintech, we offer free pump sizing guidance for all our clients, to help them find the best pumps in India for their requirements.

Once you have installed the pump, you need to monitor the flow rate periodically to determine if your pump is performing efficiently. You can check the pump’s performance by monitoring several factors. Right now, we’ll just calculate the flow rate.

You can measure the flow rate of an operating pump using either one of the following two methods:Use a flow meter – A flow meter is a simple device that does exactly what it means – it measures the amount of fluid passing through the system. Attach the flow meter to the discharge outlet. The reading on the meter gives you the flow rate of the system.

Calculate flow rate manually by collecting fluid – You can collect the fluid at the output of the pump system using a bucket or vat. Measure the collected fluid, the time taken to collect it, and reverse engineer to find the flow rate. The formula for calculating the flow rate: Flow rate = Volume of Liquid Collected / Time Taken

If there is a significant difference between desired flow rate and the actual flow rate, you can then carry on an inspection of the pump system to determine what’s wrong. Or if it’s time for a pump replacement, then Sintech Pumps, the no.1 multistage centrifugal pump manufacturers in India has an excellent range of industrial pumps for all needs. Get in touch with our team to find the right pumps for your specific needs.

8613371530291

8613371530291