documentary indonesia mud pump in river since 2006 supplier

A mud flow disaster of epic proportions—the worst of its kind in history—has been ongoing since May 29, 2006, in Sidoarjo regency in East Java, Indonesia. Nicknamed Lusi, a portmanteau of “lumpur” (mud) and its location, the mud flow has covered what is roughly equivalent to 650 football fields—double the size of New York’s Central Park—with mud that is 40 meters (130 feet) deep. Sixteen villages have been buried, more than 40,000 people displaced, and at least 13 people have died.

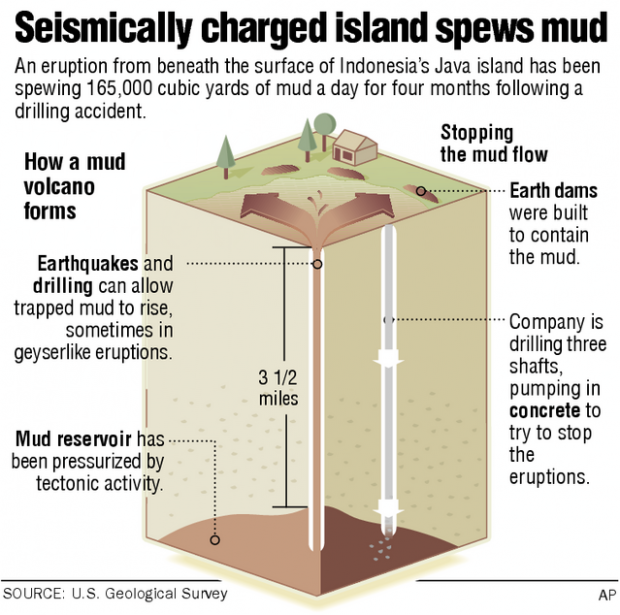

What is mindboggling is that 13 years later, Lusi continues to gush forth at a rate of 80,000 cubic meters (2.8 million cubic feet) per day, which is enough to fill 32 Olympic sized swimming pools, and weighs about 30 million pounds. This is an improvement from the early days when its peak rate was 180,000 cubic meters (6.4 million cubic feet) per day, which is equivalent to 72 Olympic sized swimming pools or 800 railroad boxcars. Earthen levees and dikes are basically what keep the mud at bay from the surrounding industrial city, and residents live in fear every day that their home will become part of the next deluge. Scientists predict the mud volcano will continue to regurgitate the sludge anywhere from another 20 to 40 years.

These facts are precisely why director Cynthia Wade was surprised to hear about Lusi for the first time as she was shooting a commercial for a nonprofit in Indonesia in 2012. When she went to investigate, she was floored by what she saw. She captured enough footage and did enough interviews to make a three-minute teaser when she returned, but she did not have the confidence and wherewithal to pursue the film further until she watched a documentary taking place in Indonesia that had been directed by Sasha Friedlander.

Wade reached out to her in 2013 and found out Friedlander was fluent in Bahasa and had also reported on the disaster when she worked in Indonesia as a journalist and translator for the “Bali Post.” Given the opportunity to dive back into a news story she had worked on, this time from the perspective of the victims, Friedlander was excited to join the project, especially since this gave her the opportunity to bring worldwide attention to the problem.

After five years, Gritmade its world premiere at the 2018 Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Film Festival in Toronto. It will be shown on PBS’ POV series on Sept. 9. The film centers on 14-year-old Dian and her family as they live during the aftermath of the disaster and fight with others for full compensation for their losses.

Even after 13 years, the question of whether the disaster is natural or manmade still hangs in the air. Scientists are divided between two camps: One side believes the eruption was triggered by a 6.3 earthquake that happened two days before in Yogyakarta, which is 260 km (161.5 miles) away from the site. The other believes oil and natural gas company PT Lapindo Brantas, is to blame, which was drilling 198 meters (650 feet) away from the eruption.

Often overlooked by the media and lost in the swirling debates within the scientific community about the causes for the eruption, the displaced victims believe Lapindo is the culprit and have waited for years to receive full compensation for their losses. On the anniversary of the eruption, the victims have annually staged and coordinated protests and demonstrations to voice their anger and demand what is rightfully theirs.

Lapindo is a joint venture among three companies. One of these companies, PT Energi Mega Persada Tbk, is directly connected to the business conglomerate Bakrie Group. Aburizal Bakrie used to be the chairman of the group before stepping down to serve in the government in 2004 as first the minister of economy and later as the minister of welfare. Despite stepping down as chairman, Bakrie remained one of the owners of the group and is a focal point of the victims’ demands and frustrations.

The initial estimate of damages in 2006 was $180 million, but by 2008 the estimate rose to $844 million and was expected to get even higher. The government mandated as early as 2007 that Bakrie pay at least half of it while also paying compensation to the victims. This is the same year Forbes Asia named Bakrie the richest man in Indonesia. Although Lapindo complied and paid the victims in irregular installments or small portions, the payments slowed down during the recession. According to Globe Asia magazine in 2008, Bakrie’s and his family’s net worth was estimated at $9.2 billion and was declared “the undisputed richest family in Indonesia.” In June 2018, Globe Asia ranked Bakrie as the 12th richest in the country with a net worth of $2.05 billion.

Bakrie Group’s control and ownership includes some of the country’s major broadcasting networks. According to the film’s directors, news about Lusi were contained and prevented from getting wide circulation domestically and internationally. Considering the rampant corruption in Indonesia, the accusation seems plausible, but searches for the news can easily be found through major news sources such as the Associated Press, Reuters and Agence France-Presse around the time of the eruption with ongoing reporting throughout the following decade.

Lusi poses environmental challenges as well. The vents at the epicenter still shoot gases such as methane and hydrogen sulphide. To help contain the mud, it has been dumped into the Porong River, which eventually leads to the Bali Sea. This has affected the local shrimp and fishing industry and may have introduced heavy metals into the water system, affecting the health of those living around the disaster. Possibly the only positive outcome is the creation of Lusi Island, a fishery with mangrove plantations that was made possible from the mud dredged from the river. Plans are in the works to make it a future tourist attraction.

Displaced residents have made a living off of Lusi by joining the disaster tourism industry, which has become more common in Indonesia due to its many earthquakes, floods and volcanic eruptions. Visitors of all types, from models to researchers, come to see Lusi, which has become a visual paradox that draws a mix of joy, wonder and curiosity while simultaneously being a source of misery.

Lapindo’s CEO announced in 2016 that the company will resume gas drilling in Sidoarjo to repay the $56.5 million loan the government gave the company which was used in part to pay off compensation claims.

The documentary follows Dian and her mother Harwati as they deal with life in the aftermath of the disaster eight years later. Harwati is a single mother raising two daughters while working seven days a week shuttling tourists on her motorbike who want to see Lusi. Her husband, who was a Lapindo employee, died a year after the disaster from cancer. As the 2014 presidential election approaches, a candidate that resonates with the demonstrators brings hope not unlike the feeling Americans experienced during the 2008 election year.

From the beginning, Wade and Friedlander understood the difficulty in marketing a film about mud and decided from the start that most of their funding would go into the cinematography, even forgoing their own payment as directors. Over the course of five years, they made nine trips where they filmed during 18 hour days, each trip lasting three weeks. The directors make no secret about who they think is to blame for the disaster: the documentary focuses on Lapindo, its role in the cause of the disaster, the people’s protests against the company, and includes an interview with Bakrie himself.

The long distance posed a significant challenge for the directors since funding was collected and saved sporadically throughout the years; there was always the possibility that the directors would not have enough money saved to make the 30-hour flight to Indonesia when something urgent happened. Fortunately, they had a local film crew that could jump in whenever they were not present.

Although the directors initially followed three separate families, they ended up focusing on Harwati since she was a vocal and involved leader and demonstrator from the start. Harwati always encourages Dian to fight against social injustice, and as the film progresses, Dian rises and becomes a voice and activist for her community with aspirations of becoming a human rights lawyer.

Grit is a powerful and moving film that captures the hauntingly arresting beauty of the disaster area with eloquent wonder. The documentary not only highlights female leadership and social activism but acts as a warning signal to people about the injustice and dodgy circumstances that can occur when a government leader is also heavily involved in business.

she heard a deep rumble and turned to see a tsunami of mud barreling towards her village. She remembers her mother scooping her up to save her from the boiling mud. Her neighbors ran for their lives. Sixteen villages, including Dian’s, were wiped away.

A decade later, nearly 60,000 people have been displaced from what was once a thriving industrial and residential area in East Java, located just 20 kilometers from Indonesia’s second largest city. Dozens of factories, schools and mosques are submerged 60 feet under a moonscape of cracked mud.

The majority of international scientists believe that Lapindo, a multinational company that was drilling for natural gas in 2006, accidentally struck an underground mud volcano and unleashed a violent flow of hot sludge from the earth"s depths. Ten years later, despite initial assurances to do so, Lapindo has not provided 80% of its promised reparations to the hundreds of victims of who lost everything in the mud explosion.

While the survivors live in the shadow of the mudflow and wait for restitution, they live in makeshift rented homes next to levees that hold back the compounding mud. With old job sites -- factories, offices – buried deep, the victims have turned the disaster site into a popular tourist destination. Dian’s mother, widowed within a year of the explosion, has reinvented herself as an unofficial mudflow tour guide in order to make ends meet. She spends her days guiding curious Indonesians across the wasteland so the tourists can snap photos of the boiling muck and thick steam that continue to spurt violently into the sky. The vast lunar landscape is littered with bizarre activities: fashion photographers take stylish photos of models posing in ball gowns; vendors sell selfie sticks, DVDs and meatballs; protesters smear mud over their bodies in stubborn acts of resistance.

Dian is determined to rise out of the muddy life. She and her mother, along with many neighbors, fight against the corporate powers accused of one of the largest environmental disasters in recent history. The film bears witness to Dian’s transformation into a politically active teenager as she questions the role of corporate power and money in the institution of democracy itself.

This article is part of the postdoctoral research project ‘Mountain, Tree and Motherland’, which was financed by the WOTRO Science of Global Development programme of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). The author would like to thank Prof. Dr Ben Arps and the crew of Gali lubang, tutup lubang for their support, as well as Dr Klarijn Anderson-Loven and two anonymous reviewers for reading and critically commenting on earlier drafts of this document.

Disasters produce creative new terms: ‘In both traditional and novel manners, language and linguistic usages emerge to express events, name the peoples and parties involved, and manage the allegiances and contestations, so that, on top of all else, disaster brings to light sociolinguistic application and invention’ (Oliver-Smith and Hoffman 2007:11). A baby born at the refugee centre in Porong, Sidoarjo, was named ‘David Lapindo’. See Nabiha Shahab, http://reliefweb.int/report/indonesia/misery-indonesias-mud-volcano-victims (accessed 15-5-2015).

Here we need to differentiate between the three shareholders mentioned in footnote 1. Minority shareholder Santos Australia did not admit liability for the mudflow incident but states in its 2007 half-year financial report that it paid approximately US$ 20 million to cover operation expenses; see http://www.santos.com/library/Santos%202007%20Half%20Year%20Results.pdf (accessed 19-4-2015). In December 2008 Santos transferred its 18 % minority share to Minarak Labuan, a company associated with Lapindo Brantas; see http://www.santos.com/annual-report-2008/asia.aspx (accessed 19-4-2015). Second-largest shareholder Medco has denied responsibility from the start, accusing Lapindo Brantas of committing ‘gross negligence’ during its drilling activities (see Medco ‘warning’ letter of 5 June 2006 addressed to Lapindo in Azhar Akbar 2007:203). In March 2007 Medco divested its 32 % stake in the Brantas Block to Prakarsa Group, which is financially guaranteed by Minarak Labuan, an affiliate of the Bakrie Group. See John Aglionby, ‘Medco sells stake in mudflow oil field’, 2007, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/c4dfe536-d762–11db-b9d7000b5df10621.html#axzz3Xzl71SXa (accessed 21-4-2015).

In September 2006 Energi Mega Persada tried to sell Lapindo Brantas for just US$ 2 to the company Lyte Ltd, which is registered at the British island of Jersey and belongs to the Bakrie conglomerate. In November 2006 the company signed a contract for sale with the British Virgin Islands-based Freehold Group Ltd, but Freehold called off the deal because of the controversy around the purchase. ‘Dari bursa hinggap di Senayan’, Tempo Interaktif 19-02-2009, http://www.tempo.co/selusur/data/sbyical/page11.php (accessed 20-4-2015).

For more detailed information on the demands of several groups of victims concerning compensation schemes, see Bosman Batubara 2010, http://www.insideindonesia.org/resistance-through-memory-2?highlight=WyJiYXR1YmFyYSIsImJhdHViYXJhJ3MiLCJib3NtYW4iXQ%3D%3D (accessed 30-10-2012), and Novenanto 2009.

John M. Glionna, ‘Indonesia’s mud volcano flows on’, 2010, http://articles.latimes.com/2010/jul/10/world/la-fg-indonesia-mudslide-20100710 (accessed 22-7-2010).

Hans David Tampubolon, ‘Endless mudflow breeds political apathy among Porong residents’, 2013, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/03/04/endless-mudflow-breeds-political-apathy-among-porong-residents.html (accessed 25-4-2013).

Pancoran, ‘Ada konspirasi SBY-Bakrie di Lumpur Lapindo, di mana?’, 2012, http://politik.kompasiana.com/2012/07/04/ada-konspirasi-sby-bakrie-di-lumpur-lapindo-di-mana-474452.html (accessed 8-9-2012).

Wahyoe Boediwardhana, ‘Lapindo book author forced to stay into hiding’, 2012, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2012/07/30/lapindo-book-author-forced-stay-hiding.html (accessed 25-4-2013).

For an overview of the Indonesian media landscape and the twelve media groups, see Merlyna Lim, ‘@Crossroads: Democratization and corporatization of media in Indonesia’, 2011, retrieved from, http://participatorymedia.lab.asu.edu/files/Lim_Media_Ford_2011.pdf (last accessed 9-6-2015).

Lapindo Brantas offered one billion rupiah to several Surabaya-based media after the Presidential Regulation was released in April 2007 (Novenanto 2009:131–2).

Hans David Tampubolon, ‘Endless mudflow breeds political apathy among Porong residents’, 2013, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/03/04/endless-mudflow-breeds-political-apathy-among-porong-residents.html (accessed 25-4-2013).

‘Penjelasan Aburizal Bakrie (ARB) tentang lumpur Lapindo’, Youtube channel of Aburizal Bakrie, http://www.youtube.com/user/bakrieaburizal?feature=watch (accessed 25-5-2015).

The documentary Di balik frekuensi (Behind the frequency) of filmmaker Ucu Agustin (2013) gives an interesting insight into the current Indonesian media landscape, which is dominated by media corporations, like the Bakrie Brothers, with strong political ties. One storyline of the film shows how mudflow victims Hari Suwandi and Harto Wiyono walked all the way from Sidoarjo to Jakarta, 847 kilometres, to seek justice concerning compensation payments. When they arrive in Jakarta, however, their act of protest suddenly turns into an act of propaganda. At this point the film uses original footage from Bakrie-owned TV One: Hari Suwandi appears during a TV One news show, telling that he regrets that he has undertaken his journey to protest. While crying, he apologizes to Aburizal Bakrie. See http://video.tvonenews.tv/arsip/view/59333/2012/07/25/hari_suwandi_sesali_aksi_jalan_kaki_porongjakarta.tvOne (last accessed 10-6-2015).

Arfi Bambani Amri and Tudji Martudji, ‘Sulastri tersenyum lebar tanahnya dibeli Minarak Lapindo: Tanahnya yang seluas 488 meter dihargai Rp 500 juta’, 2013, http://nasional.news.viva.co.id/news/read/399288-sulastri-tersenyum-lebar-tanahnya-dibeli-minarak-lapindo (accessed 20-5-2015).

An interactive talkshow, Cangkru’an (literally, ‘talking while sitting in a comfortable/relaxed way’) is set around a street-side guard post where kampung dwellers meet to hang out at night and talk about the latest social-political issues. The host interviews guests of different professions and backgrounds on hot topics, while TV watchers have the opportunity to phone in during the live show (Quinn 2012:71). One episode of Cangkru’an used the Pasar Porong refugee centre as its backdrop. Lapindo representative Nirwan Bakrie and the deputy regent talked to the mudflow victims. However, the refugees were not allowed to directly confront the guest speakers with their own questions; they received prefabricated, ‘moderated’ text written by the JTV producers (Azhar Akbar 2007:152–3).

‘Sembelih 360 kambing qurban, pecahkan rekor MURI’, 2006, http://www.antaranews.com/berita/49839/sembelih-360-kambing-qurban-pecahkan-rekor-muri (accessed 16-5-2015).

Indra Harsaputra, ‘Indonesia: TV digs a hole for Lapindo’, 2006, http://www.asiamedia.ucla.edu/article.asp?parentid=52185 (accessed 16-6-2007). Two other sources however mention a lower amount: USD 42,900; see Cindy Wockner, ‘The gods must be crazy’, 2006, http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/the-gods-must-be-crazy/story-e6freow6–1111112755014 (accessed 31-10-2010) and USD 39,000; see Peter Ritter, ‘Add soap, spin’, 2006, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1565620,00.html (accessed 16-6-2007).

Geoff Thompson, ‘Indonesian gas company funds “mud volcano” soap opera’, 2006, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2007-01-01/indonesian-gas-company-funds-mud-volcano-soap-opera/2164018 (last accessed 15-6-2015).

Cindy Wockner, ‘The gods must be crazy’, 2006, http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/the-gods-must-be-crazy/story-e6freow6–1111112755014 (accessed 31-10-2010).

Geoff Thompson, ‘Indonesian gas company funds “mud volcano” soap opera’, 2006, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2007-01-01/indonesian-gas-company-funds-mud-volcano-soap-opera/2164018 (last accessed 15-6-2015).

Here GLTL makes a reference to the Satuan Pelaksana (SATLAK, District Implementation Unit), set up in mid June 2006 by the Sidoarjo district. The committee was, together with Lapindo, in charge of relief efforts for displaced persons. Three months later the first national task force, TIMNAS, was created (Schiller, Lucas and Sulistiyanto 2008:65–6, 68).

A disclaimer at the beginning of the first episode states that any resemblance to reality is pure coincidence: ‘This sinetron is based on a fictive story with the Sidoarjo mudflow as its setting. Any resemblance to actual names, places and events is purely coincidental.’ (‘Sinetron ini mengetengahkan kisah drama fiktif yang menggunakan setting banjir lumpur Sidoarjo. Apabila ada kesamaan nama tokoh, tempat, dan peristiwa hanyalah kebetulan semata.’)

These opening lines of protagonist Ali are in the Indonesian language, whereas the remainder of the sinetron mainly uses the local Javanese dialect spoken in Surabaya, called ‘Suroboyoan’.

Cindy Wockner, ‘The gods must be crazy’, 2006, http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/the-gods-must-be-crazy/story-e6freow6–1111112755014 (accessed 31-10-2010).

At the time rumours of this type were repeatedly spread in the disaster area. The idea ‘it is not “news” unless a public official says it’ (Steele 2011:92) was integrated into this GLTL storyline where ‘high officials’ “news” ’ about incredible compensation rates leads to all kinds of emotional reactions among the victims.

Ali’s mother is called Emak or Mak throughout the sinetron. This is not a proper name, but a word that means ‘mother’; it is also a term of address for a married woman.

This daily newspaper also exists in the ‘unmediated’ world. It is part of the Jawa Pos Group and, like JTV, located in the Surabaya branch office Graha Pena (‘Pen House’), which made it into a convenient partner for joining the GLTL filming process. Journalist Eko Romeo Yudiono of this newspaper played the role of a reporter in the series. Some episodes actually depict images from the Graha Pena building and the Radar Surabaya newsroom.

‘Didedikasikan untuk anak-anak korban banjir lumpur Sidoarjo’ (GLTL 2006, credit titles episode 4). The director of this episode, Danial Rifki, made a short film called Anak-anak lumpur (Children of the mud) that depicted how children in the Sidoarjo area were coping with the disaster (Rifki 2009).

Ali: ‘Ngadepi musibah kudu sing ikhlas, Dhik. Lek gak, jaré Allah piyé?’ / Siti: ‘Eemm, bener yo jarené Mas, tapi saknoe Bapakku, gak ikhlas. Senengané ning omong banjir lumpur iku mesthi emosi.’

‘Kita tidak boleh masuk, tapi kita tetap masuk supaya gambar itu bagus. […] Background atau frame-frame kita perlu yang realita: lumpur banjir, sumur panji pengeboran, rumah tenggelam, traktor, mobil-mobil truck yang angkut pasir, debu-debu dan lain sebagainya. Sampai kita tipu-tipu pegawai Lapindo termasuk tentara, militer, kita syuting tetap. Bahwa proses kreatifitas itu adalah realita yang tidak kita buat-buat.’ Interview with Tedjo Laksana, 10-9-2007.

‘Pemain dan kru saya, kita tetap mendekati pemuda-pemuda itu supaya syuting tetap jalan. Dengan cara mendekati dengan keramah-tamahan kita. Seperti kita kasih rokok dia, kita kasih duit dia dan kita dekati dia dengan baik, maka proses produksi kita bisa lancar. […] Dan itu kita lakukan secara terus menerus. Soalnya sekali kita buat kesalahan pada masyarakat di sana, maka semua produksi kita akan hancur.’ Interview with Tedjo Laksana, 10-9-2007.

Interview with Mahmudah, Renokenongo, 12-9-2007. Renokenongo was one of the villages flooded in May 2006. By the time of the interview Mahmudah was busy handling cases of compensation payment. A year later, in October 2008, the entire village was submerged by the mudflow because the temporary dykes broke.

‘Dan akhirnya ketika saya yang main semua warga Renokenongo melihat: “Oh sekarang kan wayahi Ibu lurah!” Warga senang sekali. Dan teman-teman saya di Sidoarjo mengenali saya, karena saya kepala desa perempuan. Dan banyak yang kenal saya, akhirnya banyak yang lihat waktu itu. Teman-teman di Sidoarjo, di Jombang, di Malang, saya dibel.’

Participation in the series likely suited Mahmudah’s political agenda. Rumour goes that she had business relations with Lapindo. In 2005 she encouraged the villagers of Renokenongo to sell their land ‘for cattle-breeding’. This later turned out to be the land occupied by Lapindo for gas exploration. See Anton Novenanto, ‘Negara absen dalam kasus Lapindo, apa iya?’, 2015, http://korbanlumpur.info/2015/03/negara-absen-dalam-kasus-lapindo-apa-iya-1 (accessed 15-4-2015). Mahmudah, however, has always denied these accusations. To date (June 2015) she is still active as a spokesperson for the victims.

One of the reasons that Irianto wanted to promote the local language was because he considered it a way to counterbalance the increasing influence of Jakartan youth slang. Interview with Joko Irianto Hamid, Surabaya, 27-8-2007.

Ludruk performances, characterized by their emphasis on humour and social critic, generally feature the following elements: an opening dance (ngremo), a comic prologue consisting of sung poetry (kidung parikan), and clowning skits (dhagelan), followed by the main story (lakon)—based on local legends and stories about ordinary people—which is interspersed with dance and songs by a female impersonator. For more information on ludruk, see Supriyanto 1992; for more information on kidung parikan, see Supriyanto 2004.

‘Terusno perjuanganmu. Aku kabeh wis krungu neng tujuanmu bener […] nek saraning kèhi ilmu mara wong sing kesusahan ana ketimba lumpur iku, aku nang mburimu.’

Payment to the victims by Lapindo, through a loan from the government as agreed in December 2014 between President Jokowi and the Bakrie family, has been postponed several times but is supposedly due before the end of the fasting month in July 2015. Lapindo has to pay back the loan to the government within four years with an interest rate of 4.8%.

The Sidoarjo DisasterIn May 2006, near a densely populated city in Indonesia’s East Java called Sidoarjo, the ground erupted in a volcano of scalding hot mud. As local residents fled their homes, the hole continued to expel toxic gaseous mud, killing 20 people and displacing immediately almost 40,000. Known as the Lusi mudflow, the continuously flowing mud has submerged homes, factories, rice paddies, roads and 12 villages.

For the first several months of the mudflow, the hole expelled about 26 million gallons of mud a day, according to the government agency that oversees disaster recovery. The rate has since slowed to 7 to 15 million gallons a day, but the mudflow shows no signs of stopping. The Indonesian government has built levees to contain the mud and a system to divert the flow into the Porong River, but this infrastructure has failed to contain the mudflow and has needed to be rebuilt several times. By July 2015, the area contained an estimated 1.26 billion cubic feet of mud; experts estimated that the mud would continue to flow for another 8 to 18 years.

The Lusi mudflow has had severe impact on the region’s economy and public health. According to a 2015 article in Nature Geoscience, the disaster has cost the region more than $2.7 billion. Residents who worked in local factories have lost their jobs, and the rising lake of mud makes rebuilding impossible. The disaster has affected biodiversity in the Porong River, where fish species that cannot adapt to chemicals from the mudflow go extinct, curtailing a food source that locals previously relied upon. Since the eruption, respiratory infection cases in the area have more than doubled; however, as in all natural resource contamination cases, it is difficult to prove the causality of an illness.

Drake, Phillip. “Emergent Injustices: An Evolution of Disaster Justice in Indonesia’s Mud Volcano.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, July 18, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2514848618788359

Nuwer, Rachel. “Indonesia’s ‘Mud Volcano’ and Nine Years of Debate About Its Muck.” The New York Times, Sept. 21, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/22/science/9-years-of-muck-mud-and-debate-in-java.html

Scott, Michon. “Sidoarjo Mud Flow, Indonesia.” NASA Earth Observatory Image of the Day, Dec. 10, 2008. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/36111/sidoarjo-mud-flow-indonesia

Causation Debate and Victim CompensationThe cause of the Lusi mudflow has been hotly debated among scientists, government officials and local residents for over a decade. This debate is fraught, because the outcome will determine who is responsible for covering the cost of both disaster relief infrastructure and compensation for the victims who lost their homes. Many believe that the mudflow was triggered by gas drilling conducted by PT Lapindo Brantas, an oil and gas company that was drilling near the site just before it erupted. Others, including Lapindo, argue that the disaster was caused by a 6.3-magnitude earthquake that struck 150 miles west of the drill site two days earlier. Scientists have published conflicting studies, but as more evidence has emerged in recent years, a majority of scientists have come to support the hypothesis that Lapindo is responsible.

In 2015, an international team of scientists published a study in the journal Nature Geoscience that concluded with 99 percent certainty that Lapindo’s drilling caused the disaster. Just before the explosion, the company’s workers were probing for a new natural gas deposit in Sidoarjo when they hit a rock formation and liquid began to rush up through the drill hole. The engineers sealed the hole, but mud continued to build up underground; eventually the pressure became so great that it burst through the ground 500 feet from the drilling site. The 2015 report includes a new piece of evidence: gas readings that were initially withheld by Lapindo show that a process called liquefaction, which is the mechanism by which an earthquake would have caused the explosion, did not occur. Meanwhile, the data shows that hydrogen sulfide built in the vent in the first days of the eruption, suggesting that the mud came from two miles underground—the same depth reached by the drill. The study’s lead author argued that Lapindo failed to take standard precautions to prevent an accident: “This almost certainly could have been prevented if proper safety procedures had been taken,” Dr. Mark Tingay told the New York Times.

Immediately following the disaster, the Indonesian government refused to assign blame, citing a lack of scientific proof that Lapindo was responsible. The company is owned by the family of Aburizal Bakrie, a former cabinet minister, billionaire and leader of an influential political party, the Golkar party. The Bakrie family has a net worth of about $5.4 billion, making them one of the wealthiest families in Indonesia. Victims and commentators speculate that political corruption prevented the government from holding Lapindo accountable initially. The local residents led a sustained protest movement, staging demonstrations and filing lawsuits to demand compensation and accountability from Lapindo. For example, on the one-year anniversary of the disaster, activists erected a giant puppet representing Bakrie on the Porong embankment near the mudflow site, defying bans on demonstrations in that area.

In 2007, the Indonesian government ordered Lapindo to provide cash compensation or resettlement to victims who were in a designated “core disaster area.” This ruling caused frustration among many residents, because it relied on a map that many thought did not accurately represent the impact of the mudflow, and because the compensation was unequal. Further, compensation funds were inconsistent: families would receive money for a few months and then the payments would stop. In 2008, Lapindo claimed that it was unable to pay because it faced financial problems due to the global financial crisis. In 2014, newly elected president Joko Widodo, who had campaigned on a promise to help the Lusi victims, ordered his government to loan Lapindo $45.5 million to fund the remaining victim compensation. Lapindo promised to repay the government within four years.

The outstanding compensation payments were completed in October 2015, but some of the mudflow victims continue to organize. Despite the compensation order, Lapindo has not been held legally responsible for the disaster. In 2016, the company announced that it would resume drilling near Sidoarjo in order to pay off its debt to the government. Activists have led a campaign against this new drilling plan, including a demonstration in front of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources in Jakarta on National Anti-Mining Day in 2019. Many of the Lusi mudflow victims are still struggling to survive and simply want assurance that Lapindo’s drilling will not upend their lives again.

Drake, Phillip. “Emergent Injustices: An Evolution of Disaster Justice in Indonesia’s Mud Volcano.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, July 18, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2514848618788359

Farida, Anis. “Reconstructing Social Identity for Sustainable Future of Lumpur Lapindo victims.” Procedia Environmental Sciences 20 (2014): 468–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.059

Jensen, Fergus. “Indonesian Energy Company Plans to Resume Drilling Near Mud Volcano.” Reuters, Jan. 12, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-gas-volcano-idUSKCN0UQ1W820160112

Nuwer, Rachel. “Indonesia’s ‘Mud Volcano’ and Nine Years of Debate About Its Muck.” The New York Times, Sept. 21, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/22/science/9-years-of-muck-mud-and-debate-in-java.html

August 28, 2004 (top), November 11, 2008 (middle) and October 20, 2009 (bottom) views of the Sidoarjo mud flow. Red areas indicate vegetation in these NASA ASTER false-color satellite images.

The Sidoarjo mud flow (commonly known as Lumpur Lapindo, wherein lumpur is the Indonesian word for mud) is the result of an erupting mud volcanoPorong, Sidoarjo in East Java, Indonesia that has been in eruption since May 2006. It is the biggest mud volcano in the world; responsibility for the disaster was assigned to the blowout of a natural gas well drilled by PT Lapindo Brantas,distant earthquake that occurred in a different province.

At its peak it spewed up to 180,000 cubic meters (240,000 cu yd) of mud per day.levees since November 2008, resultant floodings regularly disrupt local highways and villages, and further breakouts of mud are still possible.

Mud volcano systems are fairly common on Earth, and particularly in the Indonesian province of East Java. Beneath the island of Java is a half-graben lying in the east–west direction, filled with over-pressured marine carbonates and marine muds.inverted extensional basin which has been geologically active since the Paleogene epoch.Oligo-Miocene period. Some of the overpressured mud escapes to the surface to form mud volcanoes, which have been observed at Sangiran Dome near Surakarta (Solo) in Central Java and near Purwodadi city, 200 km (120 mi) west of Lusi.

The East Java Basin contains a significant amount of oil and gas reserves, therefore the region is known as a major concession area for mineral exploration. The Porong subdistrict, 14 km south of Sidoarjo city, is known in the mineral industry as the Brantas Production Sharing Contract (PSC), an area of approximately 7,250 km2 which consists of three oil and gas fields: Wunut, Carat and Tanggulangin. As of 2006, three companies—Santos (18%), MedcoEnergi (32%) and PT Lapindo Brantas (50%)—had concession rights for this area; PT Lapindo Brantas acted as an operator.

On May 28, 2006, PT Lapindo Brantas targeted gas in the Kujung Formation carbonates in the Brantas PSC area by drilling a borehole named the "Banjar-Panji 1 exploration well". In the first stage of drilling the drill string first went through a thick clay seam (500–1,300 m deep), then through sands, shales, volcanic debris and finally into permeable carbonate rocks.UTC+7) on the 29th of May 2006, after the well had reached a total depth of 2,834 m (9,298 ft), this time without a protective casing, water, steam and a small amount of gas erupted at a location about 200 m southwest of the well.hydrogen sulfide gas was released and local villagers observed hot mud, thought to be at a temperature of around 60 °C (140 °F).

A magnitude 6.3 earthquake occurred in Yogyakartaloss circulation material was pumped into the well, a standard practice in drilling an oil and gas well. A day later the well suffered a ‘kick’, an influx of formation fluid into the well bore. The kick was reported by Lapindo Brantas drilling engineers as having been killed within three hours,

From a model developed by geologists working in the UK,limestone, causing entrainment of mud by water. Whilst pulling the drill string out of the well, there were ongoing losses of drilling mud, as demonstrated by the daily drilling reports stating "overpull increasing", "only 50% returns" and "unable to keep hole full".drilling for oil.

The relatively small distance, around 600 feet (180 m), between the Lusi mud volcano and the well being drilled by Lapindo (the Banjarpanji well) may not be a coincidence, as less than a day before the start of the mud flow the well suffered a kick. Their analysis suggests that the well has a low resistance to a kick.

The relatively close timing of the Yogyakarta earthquake, the problems of mud loss and kick in the well and the birth of the mud volcano continue to interest geoscientists. Was the mud volcano due to the same seismic event that triggered the earthquake? Geoscientists from Norway, Russia, France and Indonesia have suggested that the shaking caused by the Yogyakarta earthquake may have induced liquefaction of the underlying Kalibeng clay layer, releasing gases and causing a pressure change large enough to reactivate a major fault nearby (the Watukosek fault), creating a mud flow path that caused Lusi.

They have identified more than 10 naturally triggered mud volcanoes in the East Java province, with at least five near the Watukosek fault system, confirming that the region is prone to mud volcanism. They also showed that surface cracks surrounding Lusi predominantly run NE-SW, the direction of the Watukosek fault. Increased seep activity in the mud volcanoes along the Watukosek fault coincided with the May 27, 2006 seismic event. A major fault system may have been reactivated, resulting in the formation of a mud volcano.

Lusi is near the arc of volcanoes in Indonesia where geothermal activities are abundant. The nearest volcano, the Arjuno-Welirang complex, is less than 15 km away. The hot mud suggests that some form of geothermal heating from the nearby magmatic volcano may have been involved.

There was controversy as to what triggered the eruption and whether the event was a natural disaster or not. According to PT Lapindo Brantas it was the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake that triggered the mud flow eruption, and not their drilling activities.moment magnitude 6.3 hit the south coast of Central Java and Yogyakarta provinces killing 6,234 people and leaving 1.5 million homeless. At a hearing before the parliamentary members, senior executives of PT Lapindo Brantas argued that the earthquake was so powerful that it had reactivated previously inactive faults and also creating deep underground fractures, allowing the mud to breach the surface, and that their company presence was coincidental, which should exempt them from paying compensation damage to the victims.government of Indonesia has the responsibility to cover the damage instead. This argument was also recurrently echoed by Aburizal Bakrie, the Indonesian Minister of Welfare at that time, whose family firm controls the operator company PT Lapindo Brantas.

However the UK team of geologists downplayed Lapindo"s argument and concluded "...that the earthquake that occurred two days earlier is coincidental."epicenter. The intensity of the earthquake at the drilling site was estimated to have been only magnitude 2 on Richter scale, the same effect as a heavy truck passing over the area.

On June 5, 2006, MedcoEnergi (one partner company in the Brantas PSC area) sent a letter to PT Lapindo Brantas accusing them of breaching safety procedures during the drilling process.vice president Jusuf Kalla announced that PT Lapindo Brantas and the owner, the Bakrie Group, would have to compensate thousands of victims affected by the mud flows.

Aburizal Bakrie frequently said that he is not involved in the company"s operation and further distanced himself from the incident.Indonesia"s Capital Markets Supervisory Agency[Id] blocked the sale.Virgin Islands, the Freehold Group, for US$1 million, which was also halted by the government supervisory agency for being an invalid sale.bankruptcy to avoid the cost of cleanup, which could amount to US$1 billion.

On August 15, 2006, the East Java police seized the Banjar-Panji 1 well to secure it for the court case.WALHI, meanwhile had filed a lawsuit against PT Lapindo Brantas, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, the Indonesian Minister of Energy, the Indonesian Minister of Environmental Affairs and local officials.

After investigations by independent experts, police had concluded the mud flow was an "underground blow out", triggered by the drilling activity. It is further noted that steel encasing lining had not been used which could have prevented the disaster. Thirteen Lapindo Brantas" executives and engineers face twelve charges of violating Indonesian laws.

Australian artist Susan Norrie investigated the political and ecological meaning of event in a sixteen-screen video installation at the 2007 Venice Biennale.

As of October 30, 2008, the mud flow was still ongoing at a rate of 100,000 cubic meters (130,000 cu yd) per day.3 per day, with 15 bubbles around its gushing point.

After new hot gas flows began to appear, workers started relocating families and some were injured in the process. The workers were taken to a local hospital to undergo treatment for severe burns. In Siring Barat, 319 more families were displaced and in Kelurahan Jatirejo, 262 new families were expected to be affected by the new flows of gas. Protesting families took to the streets demanding compensation which in turn added more delays to the already stressed detour road for Jalan Raya Porong and the Porong-Gempol toll road.

The Indonesian government has stated that their heart is with the people. However the cabinet meeting on how to disburse compensation has been delayed until further notice. A local official Saiful Ilah signed a statement announcing that, "The government is going to defend the people of Siring." Following this announcement protests came to an end and traffic flow returned to normal an hour later.

The Australian oil and gas company Santos Limited was a minority partner in the venture until 2008. In December 2008, the company sold its 18% stake in the project to Minarak Labuan, the owner of Lapindo Brantas Inc. Labuan also received a payment from Santos of $US22.5 million ($A33.9 million) "to support long-term mud management efforts". The amount was covered by existing provision for costs relating to the incident. Santos had provisioned for $US79 million ($A119.3 million) in costs associated with the disaster. Santos had stated in June 2006 that it maintained "appropriate insurance coverage for these types of occurrences".

New mudflows spots begun in April 2010, this time on Porong Highway, which is the main road linking Surabaya with Probolinggo and islands to the east including Bali, despite roadway thickening and strengthening. A new highway is planned to replace this one however are held up by land acquisition issues. The main railway also runs by the area, which is in danger of explosions due to seepage of methane and ignition could come from something as simple as a tossed cigarette.

As of June 2009, the residents had received less than 20% of the suggested compensation. By mid-2010, reimbursement payments for victims had not been fully settled, and legal action against the company had stalled. It is worth mentioning that the owner of the energy company, Aburizal Bakrie was the Coordinating Minister for People"s Welfare at the time of the disaster, and is currently the chairman of

The Sidoarjo mud is rich in rock salt (halite) and has provided a source of income for the local residents who have been harvesting the salt for sale at the local market.

In late 2013, international scientists who had been monitoring the situation were reported as saying that the eruption of mud at Sidoardjo was falling away quite rapidly and that the indications were that the eruption might cease by perhaps 2017, much earlier than previously estimated. The scientists noted that the system was losing pressure quite rapidly and had begun pulsing rather than maintaining a steady flow. The pulsing pattern, it was believed, was a clear sign that the geological forces driving the eruption were subsiding.

By 2016 the mudflow continued with tens of thousands of liters of mud contaminated with heavy metals leaking into rivers.Sidoarjo Mudflow Handling Agency, a government-backed taskforce.

Out of the three hypotheses on the cause of the Lusi mud volcano, the hydro fracturing hypothesis appeared to be the one most debated. On 23 October 2008 a public relations agency in London, acting for one of the oil well"s owners, started to widely publicise what it described as "new facts" on the origin of the mud volcano, which were subsequently presented at an American Association of Petroleum Geologists conference in Cape Town, South Africa on 28 October 2008 (see next section)."At a recent Geological Society of London Conference, we provided authoritative new facts that make it absolutely clear that drilling could not have been the trigger of LUSI." Other verbal reports of the conference in question indicated that the assertion was by no means accepted uncritically, and that when the novel data is published, it is certain to be scrutinized closely.

In 2009, this well data was finally released and published in the Journal of Marine and Petroleum Geology for the scientific community uses by the geologists and drillers from Energi Mega Persada.

After hearing the (revised) arguments from both sides for the cause of the mud volcano at the American Association of Petroleum Geologists International Convention in Cape Town in October 2008, the vast majority of the conference session audience present (consisting of AAPG oil and gas professionals) voted in favor of the view that the Lusi (Sidoarjo) mudflow had been induced by drilling. On the basis of the arguments presented, 42 out of the 74 scientists came to the conclusion that drilling was entirely responsible, while 13 felt that a combination of drilling and earthquake activity was to blame. Only 3 thought that the earthquake was solely responsible, and 16 geoscientists believed that the evidence was inconclusive.

On the possible trigger of Lusi mud volcano, a group of geologists and drilling engineers from the oil company countered the hydro fracturing hypothesis.

In February 2010, a group led by experts from Britain"s Durham University said the new clues bolstered suspicions the catastrophe was caused by human error. In journal Marine and Petroleum Geology, Professor Richard Davies, of the Centre for Research into Earth Energy Systems (CeREES), said that drillers, looking for gas nearby, had made a series of mistakes. They had overestimated the pressure the well could tolerate, and had not placed protective casing around a section of open well. Then, after failing to find any gas, they hauled the drill out while the hole was extremely unstable. By withdrawing the drill, they exposed the wellhole to a "kick" from pressurized water and gas from surrounding rock formations. The result was a volcano-like inflow that the drillers tried in vain to stop.

In the same Marine and Petroleum Geology journal, the group of geologists and drilling engineers refuted the allegation showing that the "kick" maximum pressure were too low to fracture the rock formation.

The 2010 technical paper in this series of debate presents the first balanced overview on the anatomy of the Lusi mud volcanic system with particular emphasis on the critical uncertainties and their influence on the disaster.

In July 2013, Lupi et al. proposed that the Lusi mud eruption was the result of a natural event, triggered by a distant earthquake at Yogyakarta two days before. As a result, seismic waves were geometrically focused at the Lusi site leading to mud and CO2 generation and a reactivation of the local Watukosek Fault. According to their hypothesis the fault is linked to a deep hydrothermal system that feeds the eruption.

In June 2015, Tingay et al. used geochemical data recorded during the drilling of the Banjar Panji-1 well to test the hypothesis that the Yogyakarta earthquake triggered liquefaction and fault reactivation at the mudflow location.

Tingay, Mark; Heidbach, Oliver; Davies, Richard; Swarbrick, Richard (June 18, 2014), Tingay et al 2008 GEOLOGY Lusi triggering, retrieved October 11, 2021

Davies, Richard J.; Mathias, Simon A.; Swarbrick, Richard E.; Tingay, Mark J. (2011). "Probabilistic longevity estimate for the LUSI mud volcano, East Java". Journal of the Geological Society. 168 (2): 517–523. Bibcode:2011JGSoc.168..517D. doi:10.1144/0016-76492010-129. S2CID 131590325.

Sidoarjo mud flow from NASA"s Earth Observatory, posted December 10, 2008. This article incorporates public domain text and images from this NASA webpage.

S. J. Matthews & P. J. E. Bransden (1995). "Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic tectono-stratigraphic development of the East Java Sea Basin, Indonesia". 12 (5): 499–510. doi:10.1016/0264-8172(95)91505-J.

Richard J. Davies, Richard E. Swarbrick, Robert J. Evans and Mads Huuse (February 2007). "Birth of a mud volcano: East Java, May 29, 2006". GSA Today. 17 (2): 4. doi:. Retrieved June 27, 2013.link)

Dennis Normile (September 29, 2006). "GEOLOGY: Mud Eruption Threatens Villagers in Java". Science. 313 (5795): 1865. doi:10.1126/science.313.5795.1865. PMID 17008493. S2CID 140568625.

Sawolo, N., Sutriono, E., Istadi, B., Darmoyo, A.B. (2009). "The LUSI mud volcano triggering controversy: was it caused by drilling?". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 26 (9): 1766–1784. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.04.002.link)

Tingay, Mark (2015). "Initial pore pressures under the Lusi mud volcano, Indonesia". Interpretation. 3 (1): SE33–SE49. doi:10.1190/int-2014-0092.1. hdl:

Davies, R.J., Brumm, M., Manga, M., Rubiandini, R., Swarbrick, R., Tingay, M. (2008). "The East Java mud volcano (2006 to present): an earthquake or drilling trigger?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 272 (3–4): 627–638. Bibcode:2008E&PSL.272..627D. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.05.029.link)

Tingay, M.R.P. (2010). "Anatomy of the "Lusi" Mud Eruption, East Java". In: ASEG 2010, Sydney, Australia. 2009: NH51A–1051. Bibcode:2009AGUFMNH51A1051T.

Mazzini, A., Svensen, H., Akhmanov, G.G., Aloisi, G., Planke, S., Malthe-Sorenssen, A., Istadi, B. (2007). "Triggering and dynamic evolution of the LUSI mud volcano, Indonesia". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 261 (3–4): 375–388. Bibcode:2007E&PSL.261..375M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2007.07.001.link)

Mazzini, A., Nermoen, A., Krotkiewski, M., Podladchikov, Y., Planke, S., Svensen, H. (2009). "Strike-slip faulting as a trigger mechanism for overpressure release through piercement structures. Implications for the LUSI mud volcano, Indonesia". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 26 (9): 1751–1765. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.03.001.link)

Sudarman, S., Hendrasto, F. (2007). "Hot mud flow at Sidoarjo". In: Proceedings of the International Geological Workshop on Sidoarjo Mud Volcano, Jakarta, IAGI-BPPT- LIPI, February 20–21, 2007. Indonesia Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology, Jakarta.link)

Chris Holm (July 14, 2006). "Muckraking in Java"s gas fields". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved March 5, 2007.link)

Istadi, B., Pramono, G.H., Sumintadireja, P., Alam, S. (2009). "Simulation on growth and potential Geohazard of East Java Mud Volcano, Indonesia". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 26 (9): 1724–1739. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.03.006.link)

Sawolo, N., Sutriono, E., Istadi, B., Darmoyo, A.B. (2010). "Was LUSI caused by drilling? – Authors reply to discussion". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 27 (7): 1658–1675. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2010.01.018.link)

Lupi M, Saenger EH, Fuchs F, Miller SA (July 21, 2013). "Lusi mud eruption triggered by geometric focusing of seismic waves". Nature Geoscience. 6 (8): 642–646. Bibcode:2013NatGe...6..642L. doi:10.1038/ngeo1884.

Rudolph, Maxwell L.; Manga, Michael; Tingay, Mark; Davies, Richard J. (September 28, 2015). "Influence of seismicity on the Lusi mud eruption" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 42 (18): 2015GL065310. Bibcode:2015GeoRL..42.7436R. doi:hdl:2440/98209. ISSN 1944-8007.

Tingay, M. R. P.; Rudolph, M. L.; Manga, M.; Davies, R. J.; Wang, Chi-Yuen (2015). "Initiation of the Lusi mudflow disaster". Nature Geoscience. 8 (7): 493–494. Bibcode:2015NatGe...8..493T. doi:10.1038/ngeo2472.

Nuwer, Rachel (September 21, 2015). "Indonesia"s "Mud Volcano" and Nine Years of Debate About Its Muck". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

Worldwide, there is a considerable presence of the informal sector in SWM, particularly in low-middle income cities where formal selective collection systems for recyclable materials are not still developed [127]. Informal activities tend to intensify in times of economic crises and where imported raw materials are quite expensive. However, its inclusion in formal SWM systems remain a problematic issue and considerable attention from NGOs and scholars is arising for solving such problem [37].

In Figure 6 is reported a simplified scheme that represent the selective collection chain of the informal sector [128]. The structure is of a specific case study in China, however, the structure is similar worldwide. The informal pickers collect the waste in open dump sites, bins, roads and households for segregating recyclable materials. These people can be organized or alone, with or without transportation means, and can be merchants or simply pickers. The waste is then sold to trading points that collect the waste and sell it again to formal or informal recyclers or directly to manufactures. This structure can be recognized in many case studies within the scientific literature.

Many studies were implemented and published, in order to assess how the informal sector could be included in the formal management or recognized by the local population. For instance, in Ulaanbaatar (Mongolia), the informal sector operates in t informal neighborhoods. In these areas, illegal dumping is common, and some open fields became uncontrolled disposal sites, with waste pickers working and living near these areas. In 2004, the World Bank estimated that about 5000 to 7000 informal recyclers worked in Ulaanbaatar, and today this number could be higher due to the increase in city’s population. A study in the city revealed that most waste pickers have also higher education at a university, suggesting that the activity is due to many factors (e.g., lack of work). Informal waste pickers select recyclable materials and bring them by foot to secondary dealers for obtaining an income, who then sell larger quantities to the respective recycling industries [129].

In Blantyre (Malawi), MSW is disposed of in pits, along the road-side, or in the river. Waste pickers process and transform recyclable materials reducing the amount of waste disposed at dumpsites and decreasing the use of virgin materials needed for manufacturing. However, waste pickers are rarely recognized for their contribution. The two waste categories selected by the pickers are plastic and metals. No data are available for quantifying the number of waste pickers, however it was estimated that the maximum quantity of waste selected per day was about 20–30 kg d−1 [130]. In Harare, Zimbabwe, where the quantities of waste generated within the city are not known, the informal sector operates, mainly in open dump sites. Indeed, the waste collected by the formal collection is disposed of in dumpsites, where about 220 waste pickers worked. Waste pickers required a license to enter the dumpsite and had to wait for a worker’s signal before they could start recovering materials. It was estimated that the informal recycling sector recovered about 6–10% of waste deposited at the final disposal site (about 27–50 tons per day). Competition with others pickers was considered as the major challenge for the collectors, as well as workplace health and safety and discrimination among the population [131]. In Zavidovici (Bosnia Herzegovina), where solid waste is disposed of in open dumps, informal recycling represents the main income-generating activity for a group of ethnically discriminated households. These families contribute to the recovery of iron, copper, plastics and cardboard from MSW, reducing the waste inflow into the dump sites [132]. Finally, in Iloilo City (The Philippines), where some 170 tons of waste (about 50% of the total generated) are disposed of in an open dumpsite, approximately 300 households recover recyclable materials for selling them in local markets. A pilot project with international NGOs was implemented, in order to convert the organic waste into energy through briquette production. Results of the study show that the integration of the informal sector in the production of biomass briquettes can be a good option for implementing integrated plans for including informal recyclers, especially in areas where their activity is forbidden, as in The Philippines [133].

In Table 3, seven case studies are compared in order to assess which are the number of pickers, their organization, its source of waste, the quantities and the fractions collected per day and the main issues detected by the studies. Results reported that waste pickers operate both in low income (Zimbabwe) and high-income countries (China). Mostly, informal sector collect waste from uncontrolled open dump sites and are not recognized or organized by the local municipalities. Waste pickers can collect from 14 to 60 kg of recyclable waste per day, which comprehend WEEE, MSW and HW.

Regarding the environment and the recovery of resources, the benefits are evident in many cities. In some places informal-sector service providers are responsible for a significant percentage of waste collection. In Cairo (Egypt), the informal recycling is implemented since the recyclable waste recovered are sold to the private companies, while the organic fractions are used for breeding pigs [137]; in Dhanbad Municipality (India), informal recyclers play an important role in the plastic waste management, collecting the recyclable plastic waste from landfills, rendering environmental and social benefits [138]; In Bogotá (Colombia), informal recyclers collect materials from waste, motivated by profits, due to the free-market enterprise for recycling [136]; in Nuevo Laredo (México), where migration has increased the population to over 250,000 inhabitants, unemployed informal recyclers recovered 20 kg of aluminum cans and cardboard per day, making in one day the minimum-wage of one week of a factory worker [139]. In all these international realities, the main factors that allows the activity of the informal sector is the presence of low-income communities, unemployment, lack of MSW collection and the free management of waste.

Therefore, the activity of the informal sector contributes directly to the recovery of the materials and the reduction of environmental contamination. This practice is in accordance with the circular economy (CE) principles. The objective of the CE is closing of material loops, to prevent waste from final disposal, and transforming the resulting residual streams into new secondary resources [140]. It proposes a system where 4Rs provide alternatives to the use of raw virgin materials, making sustainability more likely [141]. The CE typically includes economic processes such as “reverse logistics” or “take back” programs that recover wastes for beneficial reuse, avoiding final disposal costs, often reducing raw material costs and even generating incomes [142]. Therefore, the inclusion of the informal sector represents a key strategy for improving the CE concepts, improving social, environmental and economic sustainability [143].

The activities of the informal sector regard the degree of formalization, from unorganized individuals in dumpsites, to well organized cooperatives. Therefore, issues such as exploitation by middlemen, child labor and high occupational health risks need to be challenged for addressing sustainability [144]. Globally, SWM remains a negative economy, where individual citizens pay the cost, the financial viability of recycling is disputed, and the sector remains vulnerable to great price volatility. Most of the collection systems in developed countries are subsidized, and also result in substantial exports of recyclables in global secondary resources supply chains. Moreover, if taxes, health insurance, child schooling and training provisions, management costs and other typical costs are included within the informal waste sector, it is not clear if the sector come back to being unsustainable economically [144].

It is recognized that a door-to-door collection service of source-separated recyclables may be one of the best solutions for improving RR. Therefore, the informal sector has the opportunity to deliver important environmental benefits, becoming an active agent of behavior change. Moreover, its activity can reduce the waste inflow into water bodies, decreasing the amount of marine litter in the oceans. The inclusion of the informal recycling should be more investigated, assessing pros and cons of its activity in different realities worldwide [144].

Hundreds of millions of people around the world lack regular access to clean water and sewerage. In many parts of the globe, obtaining water for everyday use requires an enormous diversion of time and effort. And beyond thirst and reduced productivity, the lack of clean water has very serious health consequences: Dirty water can transmit parasites, bacteria, and viruses and can inhibit sanitation, resulting in millions of cases of water-borne diseases each year, many deadly. The “global crisis in water,” as a 2006 United Nations report put it, “claims more lives through disease than any war claims through guns.” In short, the unavailability of clean water easily ranks among the most serious problems facing humanity.

Over the past decade, clean-water scarcity has been the subject of hundreds of academic studies, improving our understanding of its causes and its scope and identifying many possible solutions. At the same time, however, the problem has also been the focus of a burgeoning activist movement that tends to be less reflective and less constructive. These activists deem access to water a human right — one that is under constant assault by corporate malefactors.

These propositions raise important questions. If access to water is a human right, does every human have a right to consume as much water as he wishes, regardless of time and place? If not, to what

8613371530291

8613371530291