documentary indonesia mud pump in river since 2006 for sale

she heard a deep rumble and turned to see a tsunami of mud barreling towards her village. She remembers her mother scooping her up to save her from the boiling mud. Her neighbors ran for their lives. Sixteen villages, including Dian’s, were wiped away.

A decade later, nearly 60,000 people have been displaced from what was once a thriving industrial and residential area in East Java, located just 20 kilometers from Indonesia’s second largest city. Dozens of factories, schools and mosques are submerged 60 feet under a moonscape of cracked mud.

The majority of international scientists believe that Lapindo, a multinational company that was drilling for natural gas in 2006, accidentally struck an underground mud volcano and unleashed a violent flow of hot sludge from the earth"s depths. Ten years later, despite initial assurances to do so, Lapindo has not provided 80% of its promised reparations to the hundreds of victims of who lost everything in the mud explosion.

While the survivors live in the shadow of the mudflow and wait for restitution, they live in makeshift rented homes next to levees that hold back the compounding mud. With old job sites -- factories, offices – buried deep, the victims have turned the disaster site into a popular tourist destination. Dian’s mother, widowed within a year of the explosion, has reinvented herself as an unofficial mudflow tour guide in order to make ends meet. She spends her days guiding curious Indonesians across the wasteland so the tourists can snap photos of the boiling muck and thick steam that continue to spurt violently into the sky. The vast lunar landscape is littered with bizarre activities: fashion photographers take stylish photos of models posing in ball gowns; vendors sell selfie sticks, DVDs and meatballs; protesters smear mud over their bodies in stubborn acts of resistance.

Dian is determined to rise out of the muddy life. She and her mother, along with many neighbors, fight against the corporate powers accused of one of the largest environmental disasters in recent history. The film bears witness to Dian’s transformation into a politically active teenager as she questions the role of corporate power and money in the institution of democracy itself.

A mud flow disaster of epic proportions—the worst of its kind in history—has been ongoing since May 29, 2006, in Sidoarjo regency in East Java, Indonesia. Nicknamed Lusi, a portmanteau of “lumpur” (mud) and its location, the mud flow has covered what is roughly equivalent to 650 football fields—double the size of New York’s Central Park—with mud that is 40 meters (130 feet) deep. Sixteen villages have been buried, more than 40,000 people displaced, and at least 13 people have died.

What is mindboggling is that 13 years later, Lusi continues to gush forth at a rate of 80,000 cubic meters (2.8 million cubic feet) per day, which is enough to fill 32 Olympic sized swimming pools, and weighs about 30 million pounds. This is an improvement from the early days when its peak rate was 180,000 cubic meters (6.4 million cubic feet) per day, which is equivalent to 72 Olympic sized swimming pools or 800 railroad boxcars. Earthen levees and dikes are basically what keep the mud at bay from the surrounding industrial city, and residents live in fear every day that their home will become part of the next deluge. Scientists predict the mud volcano will continue to regurgitate the sludge anywhere from another 20 to 40 years.

These facts are precisely why director Cynthia Wade was surprised to hear about Lusi for the first time as she was shooting a commercial for a nonprofit in Indonesia in 2012. When she went to investigate, she was floored by what she saw. She captured enough footage and did enough interviews to make a three-minute teaser when she returned, but she did not have the confidence and wherewithal to pursue the film further until she watched a documentary taking place in Indonesia that had been directed by Sasha Friedlander.

Wade reached out to her in 2013 and found out Friedlander was fluent in Bahasa and had also reported on the disaster when she worked in Indonesia as a journalist and translator for the “Bali Post.” Given the opportunity to dive back into a news story she had worked on, this time from the perspective of the victims, Friedlander was excited to join the project, especially since this gave her the opportunity to bring worldwide attention to the problem.

After five years, Gritmade its world premiere at the 2018 Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Film Festival in Toronto. It will be shown on PBS’ POV series on Sept. 9. The film centers on 14-year-old Dian and her family as they live during the aftermath of the disaster and fight with others for full compensation for their losses.

Even after 13 years, the question of whether the disaster is natural or manmade still hangs in the air. Scientists are divided between two camps: One side believes the eruption was triggered by a 6.3 earthquake that happened two days before in Yogyakarta, which is 260 km (161.5 miles) away from the site. The other believes oil and natural gas company PT Lapindo Brantas, is to blame, which was drilling 198 meters (650 feet) away from the eruption.

Often overlooked by the media and lost in the swirling debates within the scientific community about the causes for the eruption, the displaced victims believe Lapindo is the culprit and have waited for years to receive full compensation for their losses. On the anniversary of the eruption, the victims have annually staged and coordinated protests and demonstrations to voice their anger and demand what is rightfully theirs.

Lapindo is a joint venture among three companies. One of these companies, PT Energi Mega Persada Tbk, is directly connected to the business conglomerate Bakrie Group. Aburizal Bakrie used to be the chairman of the group before stepping down to serve in the government in 2004 as first the minister of economy and later as the minister of welfare. Despite stepping down as chairman, Bakrie remained one of the owners of the group and is a focal point of the victims’ demands and frustrations.

The initial estimate of damages in 2006 was $180 million, but by 2008 the estimate rose to $844 million and was expected to get even higher. The government mandated as early as 2007 that Bakrie pay at least half of it while also paying compensation to the victims. This is the same year Forbes Asia named Bakrie the richest man in Indonesia. Although Lapindo complied and paid the victims in irregular installments or small portions, the payments slowed down during the recession. According to Globe Asia magazine in 2008, Bakrie’s and his family’s net worth was estimated at $9.2 billion and was declared “the undisputed richest family in Indonesia.” In June 2018, Globe Asia ranked Bakrie as the 12th richest in the country with a net worth of $2.05 billion.

Bakrie Group’s control and ownership includes some of the country’s major broadcasting networks. According to the film’s directors, news about Lusi were contained and prevented from getting wide circulation domestically and internationally. Considering the rampant corruption in Indonesia, the accusation seems plausible, but searches for the news can easily be found through major news sources such as the Associated Press, Reuters and Agence France-Presse around the time of the eruption with ongoing reporting throughout the following decade.

Lusi poses environmental challenges as well. The vents at the epicenter still shoot gases such as methane and hydrogen sulphide. To help contain the mud, it has been dumped into the Porong River, which eventually leads to the Bali Sea. This has affected the local shrimp and fishing industry and may have introduced heavy metals into the water system, affecting the health of those living around the disaster. Possibly the only positive outcome is the creation of Lusi Island, a fishery with mangrove plantations that was made possible from the mud dredged from the river. Plans are in the works to make it a future tourist attraction.

Displaced residents have made a living off of Lusi by joining the disaster tourism industry, which has become more common in Indonesia due to its many earthquakes, floods and volcanic eruptions. Visitors of all types, from models to researchers, come to see Lusi, which has become a visual paradox that draws a mix of joy, wonder and curiosity while simultaneously being a source of misery.

Lapindo’s CEO announced in 2016 that the company will resume gas drilling in Sidoarjo to repay the $56.5 million loan the government gave the company which was used in part to pay off compensation claims.

The documentary follows Dian and her mother Harwati as they deal with life in the aftermath of the disaster eight years later. Harwati is a single mother raising two daughters while working seven days a week shuttling tourists on her motorbike who want to see Lusi. Her husband, who was a Lapindo employee, died a year after the disaster from cancer. As the 2014 presidential election approaches, a candidate that resonates with the demonstrators brings hope not unlike the feeling Americans experienced during the 2008 election year.

From the beginning, Wade and Friedlander understood the difficulty in marketing a film about mud and decided from the start that most of their funding would go into the cinematography, even forgoing their own payment as directors. Over the course of five years, they made nine trips where they filmed during 18 hour days, each trip lasting three weeks. The directors make no secret about who they think is to blame for the disaster: the documentary focuses on Lapindo, its role in the cause of the disaster, the people’s protests against the company, and includes an interview with Bakrie himself.

The long distance posed a significant challenge for the directors since funding was collected and saved sporadically throughout the years; there was always the possibility that the directors would not have enough money saved to make the 30-hour flight to Indonesia when something urgent happened. Fortunately, they had a local film crew that could jump in whenever they were not present.

Although the directors initially followed three separate families, they ended up focusing on Harwati since she was a vocal and involved leader and demonstrator from the start. Harwati always encourages Dian to fight against social injustice, and as the film progresses, Dian rises and becomes a voice and activist for her community with aspirations of becoming a human rights lawyer.

Grit is a powerful and moving film that captures the hauntingly arresting beauty of the disaster area with eloquent wonder. The documentary not only highlights female leadership and social activism but acts as a warning signal to people about the injustice and dodgy circumstances that can occur when a government leader is also heavily involved in business.

On May 29, 2006, hot mud and gas began gushing from a rice field near a gas exploration well in East Java. More than a decade later, the Lusi mud flow continues on the Indonesian island. (The name is a combination of lumpur, the Indonesian word for mud, and Sidoarjo, the location of the flow).

Over the years, flows of boiling mud from Lusi have displaced more than 40,000 people, destroyed 15 villages, and caused nearly $3 billion in damage. It has become one of the most dramatic and damaging eruptions of its type. Some villages have been buried by layers of mud 40 meters (130 feet) thick. The mud, which has a consistency similar to porridge, pours constantly from Lusi’s main vent. Every thirty minutes or so, surges in the flow send plumes of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and methane shooting tens of meters into the air.

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired an image (above) of the mud flow on June 11, 2019. The dark brown areas have fresh, liquid mud on the surface; the lighter areas have dried into a hard surface that is strong enough to walk on. In the early years of the eruption, mud oozed over homes, factories, highways, and farmland. Now it spreads within a network of earthen levees, retention ponds, and distribution channels that form a rectangular grid around the main eruptive vents. Channels direct the mud into holding ponds to the north and south. Large volumes of mud get flushed into the Porong River, which flows east toward the Bali Sea.

Much about Lusi remains the subject of scientific research and vigorous debate. Many scientists who have studied Lusi think exploratory drilling for natural gas triggered the eruption. Others argue that an earthquake that occurred two days before the eruption played a more important role.

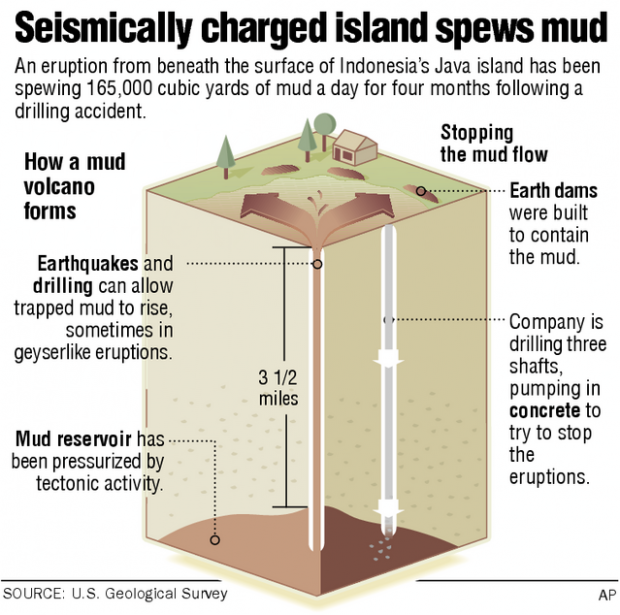

In the immediate aftermath, there were several attempts to staunch the flow of mud. The gas company pumped mud and cement down the exploratory well. Experts dropped chains of thousands of small, cement spheres into the vent to try to choke it off. And engineers built earthen levees in attempts to redirect the mud.

Yet the mud kept flowing. More than 13 years after the eruption began, about 80,000 cubic meters (3 million cubic feet) of mud still ooze from Lusi each day—enough to fill 32 Olympic-sized pools. That is down from 180,000 cubic meters during Lusi’s peak flows, but it is still quite high, explained University of Oslo geologist Adriano Mazzini.

Scientists also disagree about what makes the Lusi eruption so long-lived. Mark Tingay, a geologist at the University of Adelaide, thinks tectonic processes just happened to set up a situation in which Lusi is able to draw from an unusually large and warm reservoir of water that is under very high pressure. “This vast amount of highly pressured fluid was sitting trapped—until the seal holding these fluids down was breached,” he said. “What we are seeing is that highly pressured water being released over time.”

Mazzini argues that Lusi is connected to a neighboring volcano that provides it with a steady energy source. “Several of our studies, including gas and water geochemical surveys and ambient noise tomography, clearly show that a nearby volcanic complex and the Lusi plumbing system are connected through a fault system at a depth of about four kilometers,” he said.

Despite the disagreements about what triggered the eruption and what sustains it, many scientists expect Lusi to spew mud for a long time. “I wouldn’t be surprised to see it continue for decades,” said Michael Manga, a geologist at the University of California, Berkeley.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Drone photographs courtesy of Adriano Mazzini (University of Oslo).

Nine years ago, a rice paddy in eastern Java suddenly cleaved open and began spewing steaming mud. Before long, it covered an area twice the size of Central Park; roads, factories and homes disappeared under a tide of reeking muck. Twenty lives were lost and nearly 40,000 people displaced, with damages topping $2.7 billion.

The disaster, known as the Lusi mudflow — a combination of lumpur, the Indonesian word for mud, and Sidoarjo, the area where the eruption took place — continues today. A “mud volcano,” Lusi expels water and clay rather than molten rock. Such eruptions occur around the world, but Lusi is the biggest and most damaging known.

Scientists have debated the cause for years, and two intensely argued hypotheses have emerged: Some believe an earthquake set off the disaster, others that the mudflow was caused by a company drilling for natural gas.

Researchers largely relied on computer models and comparisons with other earthquakes and mud volcano eruptions. But recently scientists in Australia, the United States and Britain uncovered a previously overlooked set of gas readings collected at the drilling site by Lapindo Brantas, a natural gas and oil company, in the days before the mudflow began.

In a report in the journal Nature Geoscience, the researchers said that the new data proves the company caused the disaster. “We’re now 99 percent confident that the drilling hypothesis is valid,” said Mark Tingay, an earth scientist at the University of Adelaide and lead author of the paper.

Others scientists do not seem so sure. “I am surprised that the authors could arrive at such a strong conclusion from such inconclusive data,” said Stephen Miller, a professor of geodynamics and geothermics at the University of Neuchâtel in Switzerland who has published findings in support of the earthquake hypothesis. “All science screams that Lusi is natural.”

On May 27, 2006, two days before the mudflow began, a devastating 6.3 magnitude earthquake struck Yogyakarta, a city 150 miles west of a drill site in Sidoarjo, where Lapindo engineers were probing for a new natural gas deposit nearly two miles below the surface.

Eight hours after the earthquake, the engineers hit what seemed to be their target carbonate formation. Immediately, something went wrong. Fluid used to maintain pressure in the drill hole suddenly disappeared; hours later, liquid from the formation rushed back into the borehole.

Around 365 barrels of muddy water escaped the hole before the engineers, fearing a blowout, sealed it off. Though the well was capped, the leaking fluid underneath continued to build.

According to Dr. Tingay, the pressure eventually became so great as to induce its own uncontrolled version of fracking, cracking the surrounding rock and finding release nearby. The day after the well was sealed — two days after the earthquake — mud gurgled up about 500 feet from the drilling site.

Had the earthquake caused the disaster, it would have done so through a process called liquefaction, in which shaking causes rock and clay to behave like liquids. Liquefaction, Dr. Tingay and his colleagues argue, is accompanied by large gas expulsions, which would have been detected in the well.

“Every clay liquefaction event that has ever been observed has been associated with gas release,” Dr. Tingay said. But the new gas readings show no evidence of this.

On the other hand, the data does show hydrogen sulfide building a few hours before the earthquake and just as the water began rushing back into the borehole. Traces also turned up at the Lusi vent in the first days of the eruption, indicating that the mud probably came from the same depth as that reached by the drill, rather than the shallower clays that would have been liquefied in the earthquake.

ImageA villager walking through dried mud in November 2009. An explosion of steam and mud in 2006 displaced nearly 40,000 people. Much of the mud that has continually expelled since has dried.Credit...Sigit Pamungkas/Reuters

Lapindo has insisted that it followed industry safety regulations at the Sidoarjo well. But Dr. Tingay said that the company failed to fully line the borehole with casings, a standard precaution to prevent fractures.

Since the eruption, cases of respiratory infection in the area have more than doubled, and the Porong River, which receives diverted mud, is now polluted with cadmium and lead, as are fish caught and raised there. In 2007, the Indonesian government decreed that Lapindo must compensate people affected in the core disaster area.

Payments, however, have been slow to come, leading to frequent protests. In July, the government lent Lapindo — which says it has financial difficulties — funds for the remaining victims.

“There are still thousands who haven’t received compensation,” said Bambang Catur Nusantara, manager of Korbanlumpur, a nonprofit group dedicated to helping mudflow victims. “People just want to get out of this bad situation and start their new lives.”

Citing scientific uncertainty, Indonesian officials have avoided assigning blame for the disaster. “If the majority of scientists said it’s Lapindo’s fault, then maybe the government could base a decision off of that,” said Dwinanto Prasetyo, spokesman for the Sidoarjo Mudflow Handling Agency, a government-backed group in charge of mitigating the disaster.

One weakness of the new paper is the assumption that all earthquakes cause gas releases, which is not necessarily true, said David Castillo, the director of Insight GeoMechanics, a consulting company based in Perth, Australia.

Peter Flemings, a geoscientist at the University of Texas at Austin, agreed that not enough was known about earthquake-induced gas activity to rely heavily on the authors’ interpretation.

“Based on the data I have seen, I find the most plausible explanation for the Lusi mud volcano to be poor well design and flow from depth,” Dr. Flemings said.

Detailed drilling records might resolve the causation question once and for all, Dr. Tingay said, but Lapindo has declined or ignored recent requests for that data.

While debate continues about what caused Lusi, experts agree on one thing: The mud will probably continue to flow for some time, with best estimates ranging from eight to 18 years. Lusi’s mark on the land will be even longer lasting.

The Sidoarjo DisasterIn May 2006, near a densely populated city in Indonesia’s East Java called Sidoarjo, the ground erupted in a volcano of scalding hot mud. As local residents fled their homes, the hole continued to expel toxic gaseous mud, killing 20 people and displacing immediately almost 40,000. Known as the Lusi mudflow, the continuously flowing mud has submerged homes, factories, rice paddies, roads and 12 villages.

For the first several months of the mudflow, the hole expelled about 26 million gallons of mud a day, according to the government agency that oversees disaster recovery. The rate has since slowed to 7 to 15 million gallons a day, but the mudflow shows no signs of stopping. The Indonesian government has built levees to contain the mud and a system to divert the flow into the Porong River, but this infrastructure has failed to contain the mudflow and has needed to be rebuilt several times. By July 2015, the area contained an estimated 1.26 billion cubic feet of mud; experts estimated that the mud would continue to flow for another 8 to 18 years.

The Lusi mudflow has had severe impact on the region’s economy and public health. According to a 2015 article in Nature Geoscience, the disaster has cost the region more than $2.7 billion. Residents who worked in local factories have lost their jobs, and the rising lake of mud makes rebuilding impossible. The disaster has affected biodiversity in the Porong River, where fish species that cannot adapt to chemicals from the mudflow go extinct, curtailing a food source that locals previously relied upon. Since the eruption, respiratory infection cases in the area have more than doubled; however, as in all natural resource contamination cases, it is difficult to prove the causality of an illness.

Drake, Phillip. “Emergent Injustices: An Evolution of Disaster Justice in Indonesia’s Mud Volcano.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, July 18, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2514848618788359

Nuwer, Rachel. “Indonesia’s ‘Mud Volcano’ and Nine Years of Debate About Its Muck.” The New York Times, Sept. 21, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/22/science/9-years-of-muck-mud-and-debate-in-java.html

Scott, Michon. “Sidoarjo Mud Flow, Indonesia.” NASA Earth Observatory Image of the Day, Dec. 10, 2008. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/36111/sidoarjo-mud-flow-indonesia

Causation Debate and Victim CompensationThe cause of the Lusi mudflow has been hotly debated among scientists, government officials and local residents for over a decade. This debate is fraught, because the outcome will determine who is responsible for covering the cost of both disaster relief infrastructure and compensation for the victims who lost their homes. Many believe that the mudflow was triggered by gas drilling conducted by PT Lapindo Brantas, an oil and gas company that was drilling near the site just before it erupted. Others, including Lapindo, argue that the disaster was caused by a 6.3-magnitude earthquake that struck 150 miles west of the drill site two days earlier. Scientists have published conflicting studies, but as more evidence has emerged in recent years, a majority of scientists have come to support the hypothesis that Lapindo is responsible.

In 2015, an international team of scientists published a study in the journal Nature Geoscience that concluded with 99 percent certainty that Lapindo’s drilling caused the disaster. Just before the explosion, the company’s workers were probing for a new natural gas deposit in Sidoarjo when they hit a rock formation and liquid began to rush up through the drill hole. The engineers sealed the hole, but mud continued to build up underground; eventually the pressure became so great that it burst through the ground 500 feet from the drilling site. The 2015 report includes a new piece of evidence: gas readings that were initially withheld by Lapindo show that a process called liquefaction, which is the mechanism by which an earthquake would have caused the explosion, did not occur. Meanwhile, the data shows that hydrogen sulfide built in the vent in the first days of the eruption, suggesting that the mud came from two miles underground—the same depth reached by the drill. The study’s lead author argued that Lapindo failed to take standard precautions to prevent an accident: “This almost certainly could have been prevented if proper safety procedures had been taken,” Dr. Mark Tingay told the New York Times.

Immediately following the disaster, the Indonesian government refused to assign blame, citing a lack of scientific proof that Lapindo was responsible. The company is owned by the family of Aburizal Bakrie, a former cabinet minister, billionaire and leader of an influential political party, the Golkar party. The Bakrie family has a net worth of about $5.4 billion, making them one of the wealthiest families in Indonesia. Victims and commentators speculate that political corruption prevented the government from holding Lapindo accountable initially. The local residents led a sustained protest movement, staging demonstrations and filing lawsuits to demand compensation and accountability from Lapindo. For example, on the one-year anniversary of the disaster, activists erected a giant puppet representing Bakrie on the Porong embankment near the mudflow site, defying bans on demonstrations in that area.

In 2007, the Indonesian government ordered Lapindo to provide cash compensation or resettlement to victims who were in a designated “core disaster area.” This ruling caused frustration among many residents, because it relied on a map that many thought did not accurately represent the impact of the mudflow, and because the compensation was unequal. Further, compensation funds were inconsistent: families would receive money for a few months and then the payments would stop. In 2008, Lapindo claimed that it was unable to pay because it faced financial problems due to the global financial crisis. In 2014, newly elected president Joko Widodo, who had campaigned on a promise to help the Lusi victims, ordered his government to loan Lapindo $45.5 million to fund the remaining victim compensation. Lapindo promised to repay the government within four years.

The outstanding compensation payments were completed in October 2015, but some of the mudflow victims continue to organize. Despite the compensation order, Lapindo has not been held legally responsible for the disaster. In 2016, the company announced that it would resume drilling near Sidoarjo in order to pay off its debt to the government. Activists have led a campaign against this new drilling plan, including a demonstration in front of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources in Jakarta on National Anti-Mining Day in 2019. Many of the Lusi mudflow victims are still struggling to survive and simply want assurance that Lapindo’s drilling will not upend their lives again.

Drake, Phillip. “Emergent Injustices: An Evolution of Disaster Justice in Indonesia’s Mud Volcano.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, July 18, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2514848618788359

Farida, Anis. “Reconstructing Social Identity for Sustainable Future of Lumpur Lapindo victims.” Procedia Environmental Sciences 20 (2014): 468–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.059

Jensen, Fergus. “Indonesian Energy Company Plans to Resume Drilling Near Mud Volcano.” Reuters, Jan. 12, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-gas-volcano-idUSKCN0UQ1W820160112

Nuwer, Rachel. “Indonesia’s ‘Mud Volcano’ and Nine Years of Debate About Its Muck.” The New York Times, Sept. 21, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/22/science/9-years-of-muck-mud-and-debate-in-java.html

August 28, 2004 (top), November 11, 2008 (middle) and October 20, 2009 (bottom) views of the Sidoarjo mud flow. Red areas indicate vegetation in these NASA ASTER false-color satellite images.

The Sidoarjo mud flow (commonly known as Lumpur Lapindo, wherein lumpur is the Indonesian word for mud) is the result of an erupting mud volcanoPorong, Sidoarjo in East Java, Indonesia that has been in eruption since May 2006. It is the biggest mud volcano in the world; responsibility for the disaster was assigned to the blowout of a natural gas well drilled by PT Lapindo Brantas,distant earthquake that occurred in a different province.

At its peak it spewed up to 180,000 cubic meters (240,000 cu yd) of mud per day.levees since November 2008, resultant floodings regularly disrupt local highways and villages, and further breakouts of mud are still possible.

Mud volcano systems are fairly common on Earth, and particularly in the Indonesian province of East Java. Beneath the island of Java is a half-graben lying in the east–west direction, filled with over-pressured marine carbonates and marine muds.inverted extensional basin which has been geologically active since the Paleogene epoch.Oligo-Miocene period. Some of the overpressured mud escapes to the surface to form mud volcanoes, which have been observed at Sangiran Dome near Surakarta (Solo) in Central Java and near Purwodadi city, 200 km (120 mi) west of Lusi.

The East Java Basin contains a significant amount of oil and gas reserves, therefore the region is known as a major concession area for mineral exploration. The Porong subdistrict, 14 km south of Sidoarjo city, is known in the mineral industry as the Brantas Production Sharing Contract (PSC), an area of approximately 7,250 km2 which consists of three oil and gas fields: Wunut, Carat and Tanggulangin. As of 2006, three companies—Santos (18%), MedcoEnergi (32%) and PT Lapindo Brantas (50%)—had concession rights for this area; PT Lapindo Brantas acted as an operator.

On May 28, 2006, PT Lapindo Brantas targeted gas in the Kujung Formation carbonates in the Brantas PSC area by drilling a borehole named the "Banjar-Panji 1 exploration well". In the first stage of drilling the drill string first went through a thick clay seam (500–1,300 m deep), then through sands, shales, volcanic debris and finally into permeable carbonate rocks.UTC+7) on the 29th of May 2006, after the well had reached a total depth of 2,834 m (9,298 ft), this time without a protective casing, water, steam and a small amount of gas erupted at a location about 200 m southwest of the well.hydrogen sulfide gas was released and local villagers observed hot mud, thought to be at a temperature of around 60 °C (140 °F).

A magnitude 6.3 earthquake occurred in Yogyakartaloss circulation material was pumped into the well, a standard practice in drilling an oil and gas well. A day later the well suffered a ‘kick’, an influx of formation fluid into the well bore. The kick was reported by Lapindo Brantas drilling engineers as having been killed within three hours,

From a model developed by geologists working in the UK,limestone, causing entrainment of mud by water. Whilst pulling the drill string out of the well, there were ongoing losses of drilling mud, as demonstrated by the daily drilling reports stating "overpull increasing", "only 50% returns" and "unable to keep hole full".drilling for oil.

The relatively small distance, around 600 feet (180 m), between the Lusi mud volcano and the well being drilled by Lapindo (the Banjarpanji well) may not be a coincidence, as less than a day before the start of the mud flow the well suffered a kick. Their analysis suggests that the well has a low resistance to a kick.

The relatively close timing of the Yogyakarta earthquake, the problems of mud loss and kick in the well and the birth of the mud volcano continue to interest geoscientists. Was the mud volcano due to the same seismic event that triggered the earthquake? Geoscientists from Norway, Russia, France and Indonesia have suggested that the shaking caused by the Yogyakarta earthquake may have induced liquefaction of the underlying Kalibeng clay layer, releasing gases and causing a pressure change large enough to reactivate a major fault nearby (the Watukosek fault), creating a mud flow path that caused Lusi.

They have identified more than 10 naturally triggered mud volcanoes in the East Java province, with at least five near the Watukosek fault system, confirming that the region is prone to mud volcanism. They also showed that surface cracks surrounding Lusi predominantly run NE-SW, the direction of the Watukosek fault. Increased seep activity in the mud volcanoes along the Watukosek fault coincided with the May 27, 2006 seismic event. A major fault system may have been reactivated, resulting in the formation of a mud volcano.

Lusi is near the arc of volcanoes in Indonesia where geothermal activities are abundant. The nearest volcano, the Arjuno-Welirang complex, is less than 15 km away. The hot mud suggests that some form of geothermal heating from the nearby magmatic volcano may have been involved.

There was controversy as to what triggered the eruption and whether the event was a natural disaster or not. According to PT Lapindo Brantas it was the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake that triggered the mud flow eruption, and not their drilling activities.moment magnitude 6.3 hit the south coast of Central Java and Yogyakarta provinces killing 6,234 people and leaving 1.5 million homeless. At a hearing before the parliamentary members, senior executives of PT Lapindo Brantas argued that the earthquake was so powerful that it had reactivated previously inactive faults and also creating deep underground fractures, allowing the mud to breach the surface, and that their company presence was coincidental, which should exempt them from paying compensation damage to the victims.government of Indonesia has the responsibility to cover the damage instead. This argument was also recurrently echoed by Aburizal Bakrie, the Indonesian Minister of Welfare at that time, whose family firm controls the operator company PT Lapindo Brantas.

However the UK team of geologists downplayed Lapindo"s argument and concluded "...that the earthquake that occurred two days earlier is coincidental."epicenter. The intensity of the earthquake at the drilling site was estimated to have been only magnitude 2 on Richter scale, the same effect as a heavy truck passing over the area.

On June 5, 2006, MedcoEnergi (one partner company in the Brantas PSC area) sent a letter to PT Lapindo Brantas accusing them of breaching safety procedures during the drilling process.vice president Jusuf Kalla announced that PT Lapindo Brantas and the owner, the Bakrie Group, would have to compensate thousands of victims affected by the mud flows.

Aburizal Bakrie frequently said that he is not involved in the company"s operation and further distanced himself from the incident.Indonesia"s Capital Markets Supervisory Agency[Id] blocked the sale.Virgin Islands, the Freehold Group, for US$1 million, which was also halted by the government supervisory agency for being an invalid sale.bankruptcy to avoid the cost of cleanup, which could amount to US$1 billion.

On August 15, 2006, the East Java police seized the Banjar-Panji 1 well to secure it for the court case.WALHI, meanwhile had filed a lawsuit against PT Lapindo Brantas, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, the Indonesian Minister of Energy, the Indonesian Minister of Environmental Affairs and local officials.

After investigations by independent experts, police had concluded the mud flow was an "underground blow out", triggered by the drilling activity. It is further noted that steel encasing lining had not been used which could have prevented the disaster. Thirteen Lapindo Brantas" executives and engineers face twelve charges of violating Indonesian laws.

Australian artist Susan Norrie investigated the political and ecological meaning of event in a sixteen-screen video installation at the 2007 Venice Biennale.

As of October 30, 2008, the mud flow was still ongoing at a rate of 100,000 cubic meters (130,000 cu yd) per day.3 per day, with 15 bubbles around its gushing point.

After new hot gas flows began to appear, workers started relocating families and some were injured in the process. The workers were taken to a local hospital to undergo treatment for severe burns. In Siring Barat, 319 more families were displaced and in Kelurahan Jatirejo, 262 new families were expected to be affected by the new flows of gas. Protesting families took to the streets demanding compensation which in turn added more delays to the already stressed detour road for Jalan Raya Porong and the Porong-Gempol toll road.

The Indonesian government has stated that their heart is with the people. However the cabinet meeting on how to disburse compensation has been delayed until further notice. A local official Saiful Ilah signed a statement announcing that, "The government is going to defend the people of Siring." Following this announcement protests came to an end and traffic flow returned to normal an hour later.

The Australian oil and gas company Santos Limited was a minority partner in the venture until 2008. In December 2008, the company sold its 18% stake in the project to Minarak Labuan, the owner of Lapindo Brantas Inc. Labuan also received a payment from Santos of $US22.5 million ($A33.9 million) "to support long-term mud management efforts". The amount was covered by existing provision for costs relating to the incident. Santos had provisioned for $US79 million ($A119.3 million) in costs associated with the disaster. Santos had stated in June 2006 that it maintained "appropriate insurance coverage for these types of occurrences".

New mudflows spots begun in April 2010, this time on Porong Highway, which is the main road linking Surabaya with Probolinggo and islands to the east including Bali, despite roadway thickening and strengthening. A new highway is planned to replace this one however are held up by land acquisition issues. The main railway also runs by the area, which is in danger of explosions due to seepage of methane and ignition could come from something as simple as a tossed cigarette.

As of June 2009, the residents had received less than 20% of the suggested compensation. By mid-2010, reimbursement payments for victims had not been fully settled, and legal action against the company had stalled. It is worth mentioning that the owner of the energy company, Aburizal Bakrie was the Coordinating Minister for People"s Welfare at the time of the disaster, and is currently the chairman of

The Sidoarjo mud is rich in rock salt (halite) and has provided a source of income for the local residents who have been harvesting the salt for sale at the local market.

In late 2013, international scientists who had been monitoring the situation were reported as saying that the eruption of mud at Sidoardjo was falling away quite rapidly and that the indications were that the eruption might cease by perhaps 2017, much earlier than previously estimated. The scientists noted that the system was losing pressure quite rapidly and had begun pulsing rather than maintaining a steady flow. The pulsing pattern, it was believed, was a clear sign that the geological forces driving the eruption were subsiding.

By 2016 the mudflow continued with tens of thousands of liters of mud contaminated with heavy metals leaking into rivers.Sidoarjo Mudflow Handling Agency, a government-backed taskforce.

Out of the three hypotheses on the cause of the Lusi mud volcano, the hydro fracturing hypothesis appeared to be the one most debated. On 23 October 2008 a public relations agency in London, acting for one of the oil well"s owners, started to widely publicise what it described as "new facts" on the origin of the mud volcano, which were subsequently presented at an American Association of Petroleum Geologists conference in Cape Town, South Africa on 28 October 2008 (see next section)."At a recent Geological Society of London Conference, we provided authoritative new facts that make it absolutely clear that drilling could not have been the trigger of LUSI." Other verbal reports of the conference in question indicated that the assertion was by no means accepted uncritically, and that when the novel data is published, it is certain to be scrutinized closely.

In 2009, this well data was finally released and published in the Journal of Marine and Petroleum Geology for the scientific community uses by the geologists and drillers from Energi Mega Persada.

After hearing the (revised) arguments from both sides for the cause of the mud volcano at the American Association of Petroleum Geologists International Convention in Cape Town in October 2008, the vast majority of the conference session audience present (consisting of AAPG oil and gas professionals) voted in favor of the view that the Lusi (Sidoarjo) mudflow had been induced by drilling. On the basis of the arguments presented, 42 out of the 74 scientists came to the conclusion that drilling was entirely responsible, while 13 felt that a combination of drilling and earthquake activity was to blame. Only 3 thought that the earthquake was solely responsible, and 16 geoscientists believed that the evidence was inconclusive.

On the possible trigger of Lusi mud volcano, a group of geologists and drilling engineers from the oil company countered the hydro fracturing hypothesis.

In February 2010, a group led by experts from Britain"s Durham University said the new clues bolstered suspicions the catastrophe was caused by human error. In journal Marine and Petroleum Geology, Professor Richard Davies, of the Centre for Research into Earth Energy Systems (CeREES), said that drillers, looking for gas nearby, had made a series of mistakes. They had overestimated the pressure the well could tolerate, and had not placed protective casing around a section of open well. Then, after failing to find any gas, they hauled the drill out while the hole was extremely unstable. By withdrawing the drill, they exposed the wellhole to a "kick" from pressurized water and gas from surrounding rock formations. The result was a volcano-like inflow that the drillers tried in vain to stop.

In the same Marine and Petroleum Geology journal, the group of geologists and drilling engineers refuted the allegation showing that the "kick" maximum pressure were too low to fracture the rock formation.

The 2010 technical paper in this series of debate presents the first balanced overview on the anatomy of the Lusi mud volcanic system with particular emphasis on the critical uncertainties and their influence on the disaster.

In July 2013, Lupi et al. proposed that the Lusi mud eruption was the result of a natural event, triggered by a distant earthquake at Yogyakarta two days before. As a result, seismic waves were geometrically focused at the Lusi site leading to mud and CO2 generation and a reactivation of the local Watukosek Fault. According to their hypothesis the fault is linked to a deep hydrothermal system that feeds the eruption.

In June 2015, Tingay et al. used geochemical data recorded during the drilling of the Banjar Panji-1 well to test the hypothesis that the Yogyakarta earthquake triggered liquefaction and fault reactivation at the mudflow location.

Tingay, Mark; Heidbach, Oliver; Davies, Richard; Swarbrick, Richard (June 18, 2014), Tingay et al 2008 GEOLOGY Lusi triggering, retrieved October 11, 2021

Davies, Richard J.; Mathias, Simon A.; Swarbrick, Richard E.; Tingay, Mark J. (2011). "Probabilistic longevity estimate for the LUSI mud volcano, East Java". Journal of the Geological Society. 168 (2): 517–523. Bibcode:2011JGSoc.168..517D. doi:10.1144/0016-76492010-129. S2CID 131590325.

Sidoarjo mud flow from NASA"s Earth Observatory, posted December 10, 2008. This article incorporates public domain text and images from this NASA webpage.

S. J. Matthews & P. J. E. Bransden (1995). "Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic tectono-stratigraphic development of the East Java Sea Basin, Indonesia". 12 (5): 499–510. doi:10.1016/0264-8172(95)91505-J.

Richard J. Davies, Richard E. Swarbrick, Robert J. Evans and Mads Huuse (February 2007). "Birth of a mud volcano: East Java, May 29, 2006". GSA Today. 17 (2): 4. doi:. Retrieved June 27, 2013.link)

Dennis Normile (September 29, 2006). "GEOLOGY: Mud Eruption Threatens Villagers in Java". Science. 313 (5795): 1865. doi:10.1126/science.313.5795.1865. PMID 17008493. S2CID 140568625.

Sawolo, N., Sutriono, E., Istadi, B., Darmoyo, A.B. (2009). "The LUSI mud volcano triggering controversy: was it caused by drilling?". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 26 (9): 1766–1784. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.04.002.link)

Tingay, Mark (2015). "Initial pore pressures under the Lusi mud volcano, Indonesia". Interpretation. 3 (1): SE33–SE49. doi:10.1190/int-2014-0092.1. hdl:

Davies, R.J., Brumm, M., Manga, M., Rubiandini, R., Swarbrick, R., Tingay, M. (2008). "The East Java mud volcano (2006 to present): an earthquake or drilling trigger?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 272 (3–4): 627–638. Bibcode:2008E&PSL.272..627D. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.05.029.link)

Tingay, M.R.P. (2010). "Anatomy of the "Lusi" Mud Eruption, East Java". In: ASEG 2010, Sydney, Australia. 2009: NH51A–1051. Bibcode:2009AGUFMNH51A1051T.

Mazzini, A., Svensen, H., Akhmanov, G.G., Aloisi, G., Planke, S., Malthe-Sorenssen, A., Istadi, B. (2007). "Triggering and dynamic evolution of the LUSI mud volcano, Indonesia". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 261 (3–4): 375–388. Bibcode:2007E&PSL.261..375M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2007.07.001.link)

Mazzini, A., Nermoen, A., Krotkiewski, M., Podladchikov, Y., Planke, S., Svensen, H. (2009). "Strike-slip faulting as a trigger mechanism for overpressure release through piercement structures. Implications for the LUSI mud volcano, Indonesia". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 26 (9): 1751–1765. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.03.001.link)

Sudarman, S., Hendrasto, F. (2007). "Hot mud flow at Sidoarjo". In: Proceedings of the International Geological Workshop on Sidoarjo Mud Volcano, Jakarta, IAGI-BPPT- LIPI, February 20–21, 2007. Indonesia Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology, Jakarta.link)

Chris Holm (July 14, 2006). "Muckraking in Java"s gas fields". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved March 5, 2007.link)

Istadi, B., Pramono, G.H., Sumintadireja, P., Alam, S. (2009). "Simulation on growth and potential Geohazard of East Java Mud Volcano, Indonesia". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 26 (9): 1724–1739. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.03.006.link)

Sawolo, N., Sutriono, E., Istadi, B., Darmoyo, A.B. (2010). "Was LUSI caused by drilling? – Authors reply to discussion". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 27 (7): 1658–1675. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2010.01.018.link)

Lupi M, Saenger EH, Fuchs F, Miller SA (July 21, 2013). "Lusi mud eruption triggered by geometric focusing of seismic waves". Nature Geoscience. 6 (8): 642–646. Bibcode:2013NatGe...6..642L. doi:10.1038/ngeo1884.

Rudolph, Maxwell L.; Manga, Michael; Tingay, Mark; Davies, Richard J. (September 28, 2015). "Influence of seismicity on the Lusi mud eruption" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 42 (18): 2015GL065310. Bibcode:2015GeoRL..42.7436R. doi:hdl:2440/98209. ISSN 1944-8007.

Tingay, M. R. P.; Rudolph, M. L.; Manga, M.; Davies, R. J.; Wang, Chi-Yuen (2015). "Initiation of the Lusi mudflow disaster". Nature Geoscience. 8 (7): 493–494. Bibcode:2015NatGe...8..493T. doi:10.1038/ngeo2472.

Nuwer, Rachel (September 21, 2015). "Indonesia"s "Mud Volcano" and Nine Years of Debate About Its Muck". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

Hundreds of millions of people around the world lack regular access to clean water and sewerage. In many parts of the globe, obtaining water for everyday use requires an enormous diversion of time and effort. And beyond thirst and reduced productivity, the lack of clean water has very serious health consequences: Dirty water can transmit parasites, bacteria, and viruses and can inhibit sanitation, resulting in millions of cases of water-borne diseases each year, many deadly. The “global crisis in water,” as a 2006 United Nations report put it, “claims more lives through disease than any war claims through guns.” In short, the unavailability of clean water easily ranks among the most serious problems facing humanity.

Over the past decade, clean-water scarcity has been the subject of hundreds of academic studies, improving our understanding of its causes and its scope and identifying many possible solutions. At the same time, however, the problem has also been the focus of a burgeoning activist movement that tends to be less reflective and less constructive. These activists deem access to water a human right — one that is under constant assault by corporate malefactors.

These propositions raise important questions. If access to water is a human right, does every human have a right to consume as much water as he wishes, regardless of time and place? If not, to what quantity of water does each individual have a right? Does it vary by circumstance? Whose responsibility is it to provide that water to users? At whose expense? How are disputes between different users of water to be settled? How do we encourage more efficient use of water?

Unfortunately, neither Thirst nor Flow adequately addresses these practical questions arising from their core convictions. Instead, both documentaries tell us that water is part of an inviolate “global commons” that must not be owned, traded in markets, or otherwise sullied by private enterprise. Once the right-to-water premise is established, it’s not difficult to sort the Davids from the Goliaths. From Bolivia to India to small-town America, the documentaries show us how oppressed communities are rising up against profiteering multinational companies and their cronies in the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, which are colluding to trample on the people’s right to water.

Notable by its absence in Thirst and Flow is any discussion of the mounting academic research showing that it is precisely because water is un-owned, un-traded, and hence under-priced, that water delivery systems, aquifers, and watersheds are in serious peril. For the same reason, there is a substantial underinvestment in the development and deployment of new technologies for water management. And although they argue that water should be provided by the public sector, neither Thirst nor Flow remarks on the fact that the governments of poor countries have failed abjectly to provide water to hundreds of millions of thirsty people. Likewise, we never hear how overbearing government bureaucracy and regulation perpetuates water scarcity and prevents private-sector solutions to water and sewerage issues.

Water use is not a simple science. Both the amount of water and its particular uses vary significantly geographically and among consumers. It typically does not exist in nature in a form suitable for human consumption, so resources are required to test and treat it. It is heavy and difficult to control, requiring infrastructure for storage and transportation — pipes, reservoirs, testing equipment, and maintenance. Put simply, usable water, at least on a massive scale, is neither free nor natural.

The producers of Thirst and Flowdo not deny that making water usable requires these value-added services. But to them, since water resources are part of a “global commons,” only government can be their legitimate manager. However, a growing body of empirical research shows the shortcomings of government management. With expanding human populations around the world, all of whom want access to clean water and sewerage, there is an urgent need to identify and implement practical solutions to the problems of managing and delivering water — a task so vast and complex that only the private sector is likely to succeed in it.

The activists’ alternative, which would bar the owning and trading of water, would result in the further spread of the sort of inept and corrupt water management seen in many poor countries today. These countries often have government-owned pipes, but they are leaky, water is stolen or “unaccounted for,” and sewerage is non-existent. Many of these countries’ governments are semi-socialistic, so they view extra people as a burden; these governments often excuse their failure to extend state-owned services such as water, telephones, and electricity into peripheral urban areas with bureaucratic sleight-of-hand: denying the legal existence of people who live in these areas (e.g., “slum dwellers”) and refusing to recognize them as formal citizens.

Where governments fail in this way, informal entrepreneurs — not the multinational, shareholder-owned water companies attacked in Thirst and Flow — very often step into the breach. For them, every additional person represents a new opportunity to do business. They are the ones filling the water gap in the slums of the world’s poorest cities, from Nairobi to New Delhi, from Abuja to Asunción. Some deliver water on human- or donkey-powered carts, some in diesel trucks, and some even via full-scale tankers. In African cities, street vendors sell water to passersby in transparent plastic bags called “water sachets.” Some entrepreneurs, such as those on the outskirts of Delhi, operate small-scale pipe systems. Informal entrepreneurs also undertake truly unenviable tasks, such as digging out latrines with shovels and hauling the sewage away. In Indonesia, entrepreneurs have set up private sewerage systems. In many countries, including India and Kenya, entrepreneurs and nongovernmental organizations run privately-operated toilet facilities.

The transactions between these informal entrepreneurs and consumers are generally completely voluntary: entrepreneurs supply water and sewerage, and consumers willingly pay for it, because it is more reliable, and often less costly, than similar services provided by government. These private services make it possible for their customers to pursue other uses of their own time and resources, and to live better lives.

These entrepreneurs and their customers are some of the world’s poorest people. Nevertheless, they have created a thriving market to address water problems that their governments have failed to solve. The great extent of such water services throughout cities in Latin America, Africa, and Asia is testament to their success — and just as importantly, to the failure of government provision.

The demand, repeated throughout Thirst and Flow, that profit from the sale of water be abolished, would have the immediate effect of eliminating these private providers. Given that these markets were formed precisely because of government incompetence and corruption, it seems highly unlikely that governments would replace these markets with a better system. In fact, many governments have already declared the operations of the water entrepreneurs illegal. That’s why they operate in the informal sector — the black market for clean water. Abolishing water-selling profit may benefit these countries’ governments, but for citizens it could mean an immediate reduction of access to water and sewerage.

That’s not to say that the informal markets are free of problems. Because many of these markets are illegal, both the entrepreneurs and consumers face substantial risks. Informal businesses are by definition unable to establish legally enforceable contractual relations or to build their own brands. They are unable to own property and thus cannot avail themselves of bank loans and other mechanisms to grow their businesses. They live in fear of the police and often are forced to bribe local officials in order to continue their activities.

How does one reform an underground market that provides a good that not only is free of stigma (unlike, for instance, the drug trade) but also is a human necessity? An obvious solution in urban areas, particularly in slums, would be to formally recognize these small-scale entrepreneurs, thus enabling them to own their businesses and carry out their transactions legally. This would empower the entrepreneurs to take advantage of their local knowledge and to acquire the means to “scale up” their services.

In a licit, competitive market, entrepreneurs would have stronger incentives to innovate, which would in turn drive down unit costs, improve service, expand the adoption of technologies, and benefit many more customers. Formalization would also neutralize the common criticism made of many water vendors that they sell “poor quality” water. Without access to capital, which would require formality, these water vendors have little ability to improve the quality of their water. But if they were able to formalize their operations, they would likely invest in purification and monitoring technologies.

The very existence of these informal water entrepreneurs thoroughly undermines the claim that governments can be relied on to solve the water crisis and that markets cannot. The water entrepreneurs and their customers are employing the human creative drive to solve problems, to use resources more efficiently, and to improve local environmental and health conditions. For these people — among the poorest in the world — government is the problem, not the solution.

Whether the value-added services involved in making water usable — transportation, storage, treatment — come from the public or the private sector, someone has to pay for them. While both Thirst and Flow essentially ignore the informal private water entrepreneurs, they aggressively attack formal private companies supplying water to both the rich and the poor.

The Thirst claims that “private systems usually charge more than public systems right next door.” This is a false comparison of the highest order. If the government sets the price of water below the market level, the public system’s true costs can only be gauged by factoring in taxpayer contributions. As even Thirstconcedes, the cost of replacing the crumbling municipal water infrastructure in the United States will run into many billions over the coming years. Many local government officials then face a quandary: Having under-priced water for decades, they have effectively deferred costs into the future. They must raise taxes, raise water rates, or consider other arrangements, such as the private provision of water or the private maintenance of the water infrastructure. This seems particularly objectionable in water-scarce areas, because these deferred costs greatly imperil the future availability of water.

One case covered extensively in Thirst is that of Stockton, California. The city attempted to cut back on public expenditure by bringing in a private company to manage and upgrade Stockton’s water infrastructure, a plan that would, according to the mayor, save taxpayers about $175 million over twenty years. The city council agreed to a twenty-year contract with OMI-Thames Water that went into effect in August 2003. However, a consortium of residents and the local trade unions objected to the deal — they worried about public employee layoffs, reduced water quality, and price hikes — and were subsequently joined by environmental groups in a lawsuit. By 2007, the outcry forced the city to terminate the contract with the company prematurely.

But of course leaving water systems under government control does not make those services free. It only masks the costs by dispersing them among taxpayers, by deferring them until the future through municipal bonds, or by simply ignoring them and allowing infrastructure to decay until it reaches a critical point — by which time the government officials currently in office will be long gone. By undercharging for water, municipal systems often fail to generate the revenue needed to update their infrastructure to cope with increasing demand, and they fail to invest in the protection of aquifers and watersheds. Artificially low water prices can also encourage waste and discourage conservation by individual water users. Economically speaking, the costs of present consumption are being passed on to future users.

While water-system efficiency is not government’s strong suit, it is actually an explicit goal of private operators. Privately-operated water systems reflect costs more accurately, while growing revenue that can be reinvested in infrastructure. Companies do this by negotiating long-term contracts, which ensures that costs associated with replacing infrastructure can be recouped over time.

Opponents object on the grounds that higher-priced water is not feasible for the poor, and that water should be subsidized by taxpayers so that it remains “low-cost” for all. But if equity is a concern, practical steps can be taken to enact minimal mandates that would ensure everyone has access to water, while keeping the water supply managed by the private sphere. When it privatized the provision of water in 1988–89, Chile enacted an individual water subsidy system that guaranteed poorer households a certain amount of water. A study by Mark W. Rosegrant (a policy analyst) and Renato Gazmuri Schleyer (the former Chilean agriculture secretary) showed that, as a result of the combination of privatization and targeted support, household access to water between 1970 and 1994 in Chile increased from 27 percent to 94 percent in rural areas, and from 63 percent to 99 percent in urban areas.

Some activists claim that water and sewerage are a “natural monopoly” — that they are functions that only a single entity

8613371530291

8613371530291