mud pump design calculation price

Rig pump output, normally in volume per stroke, of mud pumps on the rig is one of important figures that we really need to know because we will use pump out put figures to calculate many parameters such as bottom up strokes, wash out depth, tracking drilling fluid, etc. In this post, you will learn how to calculate pump out put for triplex pump and duplex pump in bothOilfield and Metric Unit.

Positive displacements pumps are generally used on drilling rigs to pump high pressure and high volume of drilling fluids throughout a drilling system. There are several reasons why the positive displacement mud pumps are used on the rigs.

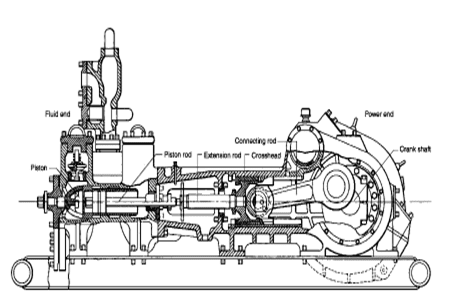

The duplex pumps (Figure 1) have two cylinders with double acting. It means that pistons move back and take in drilling mud through open intake valve and other sides of the same pistons, the pistons push mud out through the discharge valves.

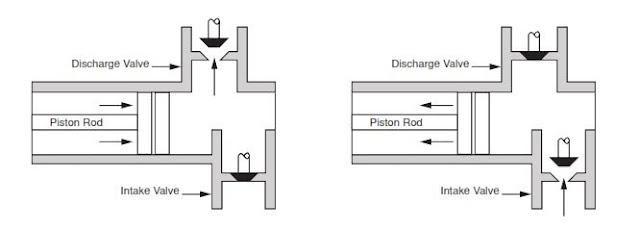

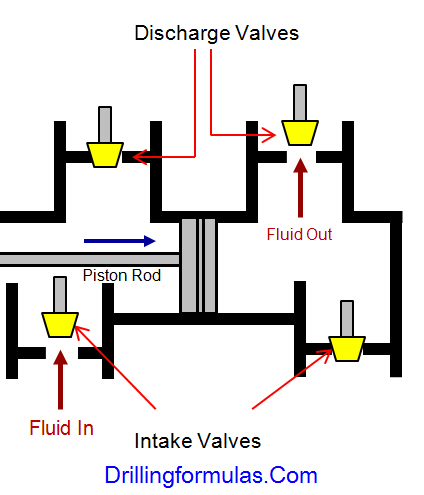

When the piston rod is moved forward, one of intake valves is lift to allow fluid to come in and one of the discharge valve is pushed up therefore the drilling mud is pumped out of the pump (Figure 2).

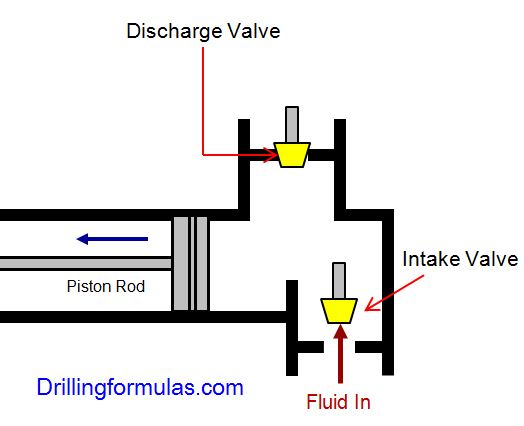

On the other hand, when the piston rod is moved backward drilling fluid is still pumped. The other intake and discharge valve will be opened (Figure 3).

The triplex pumps have three cylinders with single acting. The pistons are moved back and pull in drilling mud through open intake valves. When the pistons are moved forward and the drilling fluid is pushed out through open discharge valves.

On the contrary when the piston rods are moved backward, the intake valve are opened allowing drilling fluid coming into the pump (Figure 6). This video below shows how a triplex mud pump works.

Because each pump has power rating limit as 1600 hp, this will limit capability of pump. It means that you cannot pump at high rate and high pressure over what the pump can do. Use of a small liner will increase discharge pressure however the flow rate is reduces. Conversely, if a bigger liner is used to deliver more flow rate, maximum pump pressure will decrease.

As you can see, you can have 7500 psi with 4.5” liner but the maximum flow rate is only 297 GPM. If the biggest size of liner (7.25”) is used, the pump pressure is only 3200 psi.

Finally, we hope that this article would give you more understanding about the general idea of drilling mud pumps. Please feel free to add more comments.

The purpose of this article is to present some guidelines and simplified techniques to size pumps and piping typically used in mud systems. If unusual circumstances exist such as unusually long or complicated pipe runs or if very heavy or viscous drilling muds are used, a qualified engineer should analyze the system in detail and calculate an exact solution.

To write about pumps, one must use words that are known and well understood. For example, the label on the lefthand side of any centrifugal pump curve is Total Head Feet. What does this mean?

Total Head remains constant for a particular pump operated at a constant speed regardless of the fluid being pumped. However, a pump’s pressure will increase as the fluid density (mud weight) increases according to the following relationship:

Note that the pump pressure almost doubled. It follows that the required pump horsepower has increased by the same percentage. If the pump required 50 HP for water service, it will require the following horsepower for 16 lb/gal mud:

To summarize, a pump’s Total Head remains constant for any fluid pumped, only the pump pressure and pump horsepower will change. Therefore, a pump motor must be sized according to the heaviest weight mud to be pumped.

In our example problem, the required desilter pressure head is 75 ft. for any mud weight. However, the pressure would be 30.3 PSIG for water or 43.6 PSIG for 12 lb mud or 58.1 PSIG for 16 lb mud. A good rule of thumb is that the required pressure (PSIG) equals 4 times the mud weight (12 LB/GAL x 4 = 48 PSIG).

Determine the required pressure head and flow rate. If the pump is to supply a device such as a mud mixing hopper or a desilter, consult the manufacturer’s information or sales representative to determine the optimum flow rate and pressure head required at the device. (On devices like desilters the pressure head losses downstream of the device are considered negligible and are usually disregarded.)

Select the basic pump to pump the desired flow rate. Its best to refer to a manufacturer’s pump curve for your particular pump. (See example – Figure 3).

The pump’s impeller may be machined to a smaller diameter to reduce its pressure for a given application. Refer to the manufacturer’s pump curves or manufacturer’s representative to determine the proper impeller diameter. Excessive pressure and flow should be avoided for the following reasons:

The pump must produce more than 75 FT-HD at the pump if 75 FT-HD is to be available at the desilter inlet and the pump’s capacity must be at least 800 GPM. Therefore, we should consider using one of the following pumps from the above list: 4″ x 5″ Pump 1750 RPM – 1000 GPM at 160 FT-HD; or 5″ x 6″ Pump 1750 RPM – 1200 GPM at 160 FT-HD.

The pump suction and discharge piping is generally the same diameter as the pump flange diameters. The resulting fluid velocities will then be within the recommended ranges of 4 to 10 FT/SEC for suction lines and 4 to 12 FT/

SEC for discharge lines. Circumstances may dictate that other pipe diameters be used, but remember to try to stay within the above velocity guidelines. Smaller pump discharge piping will create larger pressure drops in the piping

and the pump may not be able to pump the required amount of fluid. (For example, don’t use a 4″ discharge pipe on a 6″ x 8″ pump and expect the pump’s full fluid flow.)

6″ pipe may be used for the suction pipe since it is relatively short and straight and the pump suction is always flooded. 6″ pipe is fully acceptable for the discharge pipe and is a good choice since the desired header is probably 6″ pipe.

8″ pipe may be used for the suction pipe (V = 5.13 FT/SEC) since V is still greater than 4 FT/SEC. 8″ pipe would be preferred if the suction is long or the suction pit fluid level is low with respect to the pump.

For contour impeller applications, values must be significantly faster (i.e., smaller numbers) to achieve the same results, but because of the impeller design, air entrainment is less probable. In symmetrical compartments, the fluid has a nearly equal distance to travel from the center of the impeller shaft or from the impeller blade tip before it contacts the vessel wall. Agitators should be placed where the shaft is centered in the tank or compartment.

For round tanks with dish or cone bottoms, calculations for working fluid volume are based on straight wall height (i.e., this height is measured from the tank top to where the tank joins the cone or dish at the bottom). This leaves adequate free space above the maximum fluid operating level. In all cases, if H<5 feet (1.5 m), a radial flow impeller should be specified.

When choosing a size and type of mud pump for your drilling project, there are several factors to consider. These would include not only cost and size of pump that best fits your drilling rig, but also the diameter, depth and hole conditions you are drilling through. I know that this sounds like a lot to consider, but if you are set up the right way before the job starts, you will thank me later.

Recommended practice is to maintain a minimum of 100 to 150 feet per minute of uphole velocity for drill cuttings. Larger diameter wells for irrigation, agriculture or municipalities may violate this rule, because it may not be economically feasible to pump this much mud for the job. Uphole velocity is determined by the flow rate of the mud system, diameter of the borehole and the diameter of the drill pipe. There are many tools, including handbooks, rule of thumb, slide rule calculators and now apps on your handheld device, to calculate velocity. It is always good to remember the time it takes to get the cuttings off the bottom of the well. If you are drilling at 200 feet, then a 100-foot-per-minute velocity means that it would take two minutes to get the cuttings out of the hole. This is always a good reminder of what you are drilling through and how long ago it was that you drilled it. Ground conditions and rock formations are ever changing as you go deeper. Wouldn’t it be nice if they all remained the same?

Centrifugal-style mud pumps are very popular in our industry due to their size and weight, as well as flow rate capacity for an affordable price. There are many models and brands out there, and most of them are very good value. How does a centrifugal mud pump work? The rotation of the impeller accelerates the fluid into the volute or diffuser chamber. The added energy from the acceleration increases the velocity and pressure of the fluid. These pumps are known to be very inefficient. This means that it takes more energy to increase the flow and pressure of the fluid when compared to a piston-style pump. However, you have a significant advantage in flow rates from a centrifugal pump versus a piston pump. If you are drilling deeper wells with heavier cuttings, you will be forced at some point to use a piston-style mud pump. They have much higher efficiencies in transferring the input energy into flow and pressure, therefore resulting in much higher pressure capabilities.

Piston-style mud pumps utilize a piston or plunger that travels back and forth in a chamber known as a cylinder. These pumps are also called “positive displacement” pumps because they literally push the fluid forward. This fluid builds up pressure and forces a spring-loaded valve to open and allow the fluid to escape into the discharge piping of the pump and then down the borehole. Since the expansion process is much smaller (almost insignificant) compared to a centrifugal pump, there is much lower energy loss. Plunger-style pumps can develop upwards of 15,000 psi for well treatments and hydraulic fracturing. Centrifugal pumps, in comparison, usually operate below 300 psi. If you are comparing most drilling pumps, centrifugal pumps operate from 60 to 125 psi and piston pumps operate around 150 to 300 psi. There are many exceptions and special applications for drilling, but these numbers should cover 80 percent of all equipment operating out there.

The restriction of putting a piston-style mud pump onto drilling rigs has always been the physical size and weight to provide adequate flow and pressure to your drilling fluid. Because of this, the industry needed a new solution to this age-old issue.

As the senior design engineer for Ingersoll-Rand’s Deephole Drilling Business Unit, I had the distinct pleasure of working with him and incorporating his Centerline Mud Pump into our drilling rig platforms.

In the late ’90s — and perhaps even earlier — Ingersoll-Rand had tried several times to develop a hydraulic-driven mud pump that would last an acceptable life- and duty-cycle for a well drilling contractor. With all of our resources and design wisdom, we were unable to solve this problem. Not only did Miller provide a solution, thus saving the size and weight of a typical gear-driven mud pump, he also provided a new offering — a mono-cylinder mud pump. This double-acting piston pump provided as much mud flow and pressure as a standard 5 X 6 duplex pump with incredible size and weight savings.

The true innovation was providing the well driller a solution for their mud pump requirements that was the right size and weight to integrate into both existing and new drilling rigs. Regardless of drill rig manufacturer and hydraulic system design, Centerline has provided a mud pump integration on hundreds of customer’s drilling rigs. Both mono-cylinder and duplex-cylinder pumps can fit nicely on the deck, across the frame or even be configured for under-deck mounting. This would not be possible with conventional mud pump designs.

Centerline stuck with their original design through all of the typical trials and tribulations that come with a new product integration. Over the course of the first several years, Miller found out that even the best of the highest quality hydraulic cylinders, valves and seals were not truly what they were represented to be. He then set off on an endeavor to bring everything in-house and began manufacturing all of his own components, including hydraulic valves. This gave him complete control over the quality of components that go into the finished product.

The second generation design for the Centerline Mud Pump is expected later this year, and I believe it will be a true game changer for this industry. It also will open up the application to many other industries that require a heavier-duty cycle for a piston pump application.

Pumps tend to be one of the biggest energy consumers in industrial operations. Pump motors, specifically, require a lot of energy. For instance, a 2500 HP triplex pump used for frac jobs can consume almost 2000 kW of power, meaning a full day of fracking can cost several thousand dollars in energy costs alone!

So, naturally, operators should want to maximize energy efficiency to get the most for their money. Even a 1% improvement in efficiency can decrease annual pumping costs by tens of thousands of dollars. The payoff is worth the effort. And if you want to remotely control your pumps, you want to keep efficiency in mind.

In this post, we’ll point you in the right direction and discuss all things related to pump efficiency. We’ll conclude with several tips for how you can maintain pumping efficiency and keep your energy costs down as much as possible.

In simple terms, pump efficiency refers to the ratio of power out to power in. It’s the mechanical power input at the pump shaft, measured in horsepower (HP), compared to the hydraulic power of the liquid output, also measured in HP. For instance, if a pump requires 1000 HP to operate and produces 800 HP of hydraulic power, it would have an efficiency of 80%.

Remember: pumps have to be driven by something, i.e., an electric or diesel motor. True pump system efficiency needs to factor in the efficiency of both the motor AND the pump.

Consequently, we need to think about how electrical power (when using electric motors) or heat power (when using combustion engines) converts into liquid power to really understand pump efficiency.

Good pump efficiency depends, of course, on pump type and size. High-quality pumps that are well-maintained can achieve efficiencies of 90% or higher, while smaller pumps tend to be less efficient. In general, if you take good care of your pumps, you should be able to achieve 70-90% pump efficiency.

Now that we have a better understanding of the pump efficiency metric, let’s talk about how to calculate it. The mechanical power of the pump, or the input power, is a property of the pump itself and will be documented during the pump setup. The output power, or hydraulic power, is calculated as the liquid flow rate multiplied by the "total head" of the system.

IMPORTANT: to calculate true head, you also need to factor in the work the pump does to move fluid from the source. For example, if the source water is below the pump, you need to account for the extra work the pump puts in to draw source water upwards.

*Note - this calculation assumes the pump inlet is not pressurized and that friction losses are minimal. If the pump experiences a non-zero suction pressure, or if there is significant friction caused by the distance or material of the pipe, these should be factored in as well.

You"ll notice that the elevation head is minimal compared to the discharge pressure, and has minimal effect on the efficiency of the pump. As the elevation change increases or the discharge pressure decreases, however, elevation change will have a greater impact on total head.

Obviously, that’s a fair amount of math to get at the pump efficiency, considering all of the units conversions that need to be done. To avoid doing these calculations manually, feel free to use our simple pump efficiency calculator.

Our calculations use static variables (pump-rated horsepower and water source elevation) and dynamic variables (discharge flow and pressure). To determine pump efficiency, we need to measure the static variables only once, unless they change.

If you want to measure the true efficiency of your pump, taking energy consumption into account, you could add an electrical meter. Your meter should consist of a current transducer and voltage monitor (if using DC) for electrical motors or a fuel gauge for combustion. This would give you a true understanding of how pump efficiency affects energy consumption, and ultimately your bank account.

Up until this point, we’ve covered the ins and outs of how to determine pump efficiency. We’re now ready for the exciting stuff - how to improve pump efficiency!

One of the easiest ways to improve pump efficiency is to actually monitor pumps for signs of efficiency loss! If you monitor flow rate and discharge (output power) along with motor current or fuel consumption, you’ll notice efficiency losses as soon as they occur. Simply having pump efficiency information on hand empowers you to take action.

Another way to increase efficiency is to keep pumps well-maintained. Efficiency losses mostly come from mechanical defects in pumps, e.g., friction, leakages, and component failures. You can mitigate these issues through regular maintenance that keeps parts in working order and reveals impending failures. Of course, if you are continuously monitoring your pumps for efficiency drops, you’ll know exactly when maintenance is due.

You can also improve pump efficiency by keeping pumps lubricated at all times. Lubrication is the enemy of friction, which is the enemy of efficiency (“the enemy of my enemy is my friend…”).

A fourth way to enhance pump efficiency is to ensure your pumps and piping are sized properly for your infrastructure. Although we’re bringing this up last, it’s really the first step in any pumping operation. If your pumps and piping don’t match, no amount of lubricant or maintenance will help.

In this post, we’ve given you the full rundown when it comes to calculating and improving pump efficiency. You can now calculate, measure, and improve pump efficiency, potentially saving your business thousands of dollars annually on energy costs.

For those just getting started with pump optimization, we offer purpose-built, prepackaged solutions that will have you monitoring pump efficiency in minutes, even in hazardous environments.

A thorough knowledge of the mud temperature profiles developed during well drilling and profiles developed during well drilling and subsequent periods of well logging is helpful. Complete temperature profiles for the fluid in both the pipe and the annulus may aid in revealing information about downhole conditions. Accurate prediction of maximum temperatures to be encountered prediction of maximum temperatures to be encountered during drilling allows for precise mud selection and preparation. The mud profiles also give indication of formation characteristics of the rock contacted during drilling. The object of this investigation was to develop an analytical mathematical model that could be used to predict the mud temperature in the drill pipe and annulus during drilling at any depth in the well.

The model is a solution of the steady-state equation for the heat transfer between the fluids in the annulus and the fluids in the drill pipe. This is combined with an approximate equation for the transient heat transfer between the fluid in the annulus and in the formation. The approximate method is adequate since the total heat transfer between the two fluids is much greater than that between the annulus fluid and the formation. The low heat transfer between the annulus fluid and the formation is a result of the relatively low thermal conductivity of the formation and the film resistance to beat transfer formed at the interface of the mud and the rock. Temperatures can be calculated as a function of well depth, mud circulation rate, circulating fluid characteristics, reservoir properties, and wellbore and drill-pipe size. properties, and wellbore and drill-pipe size. Previous Studies Previous Studies Farris has developed charts that depict the bottomhole temperature during cementing periods. These charts represent a commonly used basis for choosing oil-well cements and for predicting bottom-hole cementing temperatures. Crawford et al. has developed a method based upon the work of Edwardson et al. to calculate the bottom-hole circulating temperature as a function of well depth, casing and hole size, pumping rate and time, fluid characteristics, reservoir physical properties and the thermal status of the well. properties and the thermal status of the well. Their method represents a numerical solution for the transient beat transfer at a given depth.

8613371530291

8613371530291