mud pump packing free sample

If you run a mud rig, you have probably figured out that the mud pump is the heart of the rig. Without it, drilling stops. Keeping your pump in good shape is key to productivity. There are some tricks I have learned over the years to keeping a pump running well.

First, you need a baseline to know how well your pump is doing. When it’s freshly rebuilt, it will be at the top efficiency. An easy way to establish this efficiency is to pump through an orifice at a known rate with a known fluid. When I rig up, I hook my water truck to my pump and pump through my mixing hopper at idle. My hopper has a ½-inch nozzle in it, so at idle I see about 80 psi on the pump when it’s fresh. Since I’m pumping clear water at a known rate, I do this on every job.

As time goes on and I drill more hole, and the pump wears, I start seeing a decrease in my initial pressure — 75, then 70, then 65, etc. This tells me I better order parts. Funny thing is, I don’t usually notice it when drilling. After all, I am running it a lot faster, and it’s hard to tell the difference in a few gallons a minute until it really goes south. This method has saved me quite a bit on parts over the years. When the swabs wear they start to leak. This bypass pushes mud around the swab, against the liners, greatly accelerating wear. By changing the swab at the first sign of bypass, I am able to get at least three sets of swabs before I have to change liners. This saves money.

Before I figured this out, I would sometimes have to run swabs to complete failure. (I was just a hand then, so it wasn’t my rig.) When I tore the pump down to put in swabs, lo-and-behold, the liners were cut so badly that they had to be changed too. That is false economy. Clean mud helps too. A desander will pay for itself in pump parts quicker than you think, and make a better hole to boot. Pump rods and packing last longer if they are washed and lubricated. In the oilfield, we use a petroleum-based lube, but that it not a good idea in the water well business. I generally use water and dish soap. Sometimes it tends to foam too much, so I add a few tablets of an over the counter, anti-gas product, like Di-Gel or Gas-Ex, to cut the foaming.

Maintenance on the gear end of your pump is important, too. Maintenance is WAY cheaper than repair. The first, and most important, thing is clean oil. On a duplex pump, there is a packing gland called an oil-stop on the gear end of the rod. This is often overlooked because the pump pumps just as well with a bad oil-stop. But as soon as the fluid end packing starts leaking, it pumps mud and abrasive sand into the gear end. This is a recipe for disaster. Eventually, all gear ends start knocking. The driller should notice this, and start planning. A lot of times, a driller will change the oil and go to a higher viscosity oil, thinking this will help cushion the knock. Wrong. Most smaller duplex pumps are splash lubricated. Thicker oil does not splash as well, and actually starves the bearings of lubrication and accelerates wear. I use 85W90 in my pumps. A thicker 90W140 weight wears them out a lot quicker. You can improve the “climbing” ability of the oil with an additive, like Lucas, if you want. That seems to help.

Outside the pump, but still an important part of the system, is the pop-off, or pressure relief valve. When you plug the bit, or your brother-in-law closes the discharge valve on a running pump, something has to give. Without a good, tested pop-off, the part that fails will be hard to fix, expensive and probably hurt somebody. Pop-off valve are easily overlooked. If you pump cement through your rig pump, it should be a standard part of the cleanup procedure. Remove the shear pin and wash through the valve. In the old days, these valves were made to use a common nail as the shear pin, but now nails come in so many grades that they are no longer a reliable tool. Rated shear pins are available for this. In no case should you ever run an Allen wrench! They are hardened steel and will hurt somebody or destroy your pump.

One last thing that helps pump maintenance is a good pulsation dampener. It should be close to the pump discharge, properly sized and drained after every job. Bet you never thought of that one. If your pump discharge goes straight to the standpipe, when you finish the job your standpipe is still full of fluid. Eventually the pulsation dampener will water-log and become useless. This is hard on the gear end of the pump. Open a valve that drains it at the end of every job. It’ll make your pump run smoother and longer.

Long ago, companies didn’t want to switch to mechanical seals because of the complicated installation and need to completely disassemble the equipment. The invention of cartridge and split mechanical seals effectively eliminated those dilemmas, but many operations have stayed with pump packing out of sheer habit in situations in which seals would provide a better return.

Likewise, some customers will try to make a mechanical seal fit into an application where packing makes more sense. In this post, we’ll provide information on making the best sealing choice based on operational priorities, applications, and budget.

A mechanical seal, and more specifically a double mechanical seal, should always be used when the pumped fluid presents a safety, health, or environmental hazard. Packing cannot be 100% leak free. Even when leakage isn’t visible, harmful vapors could be escaping. This is also true for single mechanical seals.

If reliability is a primary factor, the clear choice is mechanical seals. And although the initial investment is considerably higher than pump packing, it will pay off long term. The decision to go with a mechanical seal comes with a level of commitment to achieve a true return-on-investment. A good seal vendor will help you select the correct seal design, make sure you have the most effective installation/support setup for the conditions, ensure that the equipment is in the proper condition to support the mechanical seal, and outline the regular maintenance schedule (topics we will covering in upcoming blogs). These commitments will ensure that the seal investment will pay off for many years.

Leakage/Loss of Valued ProductWhile compression packing doesn’t necessarily need to leak, typically there will be some leakage. Depending on the application and the fluid being sealed, this may be considerable. And due to the typically lower lifespan of packing, the leakage associated with failure will occur more frequently. In some instances, this is not an issue. However, it is often a safety issue due to the type of product or the volume of leakage (and/or lack of maintenance staff to routinely clean up the mess).In some cases, our customers find that the savings in lost product actually pays for the cost of the new mechanical seal very quickly. We recommend measuring the loss of product for a single pump for a week (including the clean-up maintenance labor)…then calculating for the year, multiplied by similar pumps across your operation. The results are often eye-opening and often make for an easy return-on-investment conclusion for moving to mechanical seals.

The decision to move to mechanical seals is often driven by the impact of constant leakage from packing on the shaft; bearings; safety; and maintenance.

Maintenance SupportPacking requires more labor to routinely adjust and repack as well as the frequent leakage cleanup noted above. Is your organization adequately staffed? This, too, may be a deciding factor.

Stuffing Box AccessibilityBecause packing will wear over time and require gland adjustments, the stuffing box must be accessible to maintain the packing.

Product Contamination/DilutionSince many sealing applications require the packing to include a flush to cool, the cost to remove the flush water or the possible contamination may be an issue in some applications.

Premature Bearing FailureMaintenance staffs often use a water hose to rinse leaking product away from base plates, and the excess moisture from failed packing can wreak havoc with bearings.

Sleeve damage is a frequent occurrence and costly— not only because of the sleeve cost, but also the expense involved in the sleeve removal. Packing removal almost always means changing the bearings and wear rings. Many parts also get broken or lost when pumps are disassembled.

In many cases, compression packing IS still the right answer for rotating equipment applications. When the factors above are not an issue and adequate staff is available for adjustments and repacking, packing offers a low up-front cost and fairly simple maintenance. And although some say that packing requires more energy than mechanical seals, our testing has found that they are essentially the same.

Cost: Packing provides a lower up-front cost than mechanical seals. The benefit of the mechanical seal has to outweigh this cost. This can be more difficult when the equipment is large, or requires more costly metals and elastomers.

Ease of installation/Turnaround time: Installation of packing rings does not require decoupling of drive shaft unlike in case of installing the non-split mechanical seals. This leads to a relatively easier installation and shorter turnaround time.

Equipment condition: Mechanical seals typically require equipment to be in good condition to operate reliably. This includes shaft finish, pump/driver alignment, cavitation, and vibration.

Radial/axial motion and misalignment:Most mechanical seals tolerate very little radial movement or misalignment, and little to no axial movement. If the shaft is often moved axially, such as with many paper refiners, packing is often the only option available. While these issues can sometimes be addressed with the right choice of mechanical seal and support system, packing is typically the optimal choice.

One area where these factors align is in large slurry pumps, such as those found in the mining and ore processing industry. Though mechanical seals will provide an excellent seal for some of this equipment, the confluence of the expense due to large equipment size, large shaft movements due to large particles impacting the impeller, and abrasive media leads to most customers choosing to pack their equipment.

Today’s packing advances also mean that packing will last longer in many situations and require fewer adjustments than the basic options available in the past. New materials such as carbon fiber, advanced lubricants, and new braiding technology translate to longer packing life and fewer maintenance and equipment wear issues. Learn about these different technology advances in an upcoming post.

Raman Hanjra is Global Product Line Manager of Packing & Gaskets for A.W. Chesterton Company. He holds a BS in Mechanical Engineering and an MBA in Product & Market Development and Supply Chain Management. He started his career as a sales engineer for mechanical seals and has held various sales, marketing and product leadership positions globally. In his free time, Raman enjoys photography, golf, and reading about international trade and macroeconomics.

Mystique Mud pump Coolant and Lubricant extends mud pump liner and piston life and provides internal lubrication and extra cooling to the coolant system of mud pumps. It extends the life of all liners, even ceramic. Mystique will not cause corrosion or rusting of iron, and is safe with all alloys. Recommened dilution rate of 12.5%. (25 gallons will treat a 200-gallon system.) For use on closed systems.

Then we collaborated with customers located throughout North America for more than a year to test Redline Packing and ensure its success across a variety of challenging environments. The results are remarkable, showing almost a two-fold increase in life vs the top competitor. Redline Packing is available today for GD Energy Products frac and well service pumps, and most competitor’s pumps as well.

This invention relates generally to piston pumps for the water well drilling industry, and more particularly to a hydraulic cylinder powered double acting duplex piston pump.

Double acting duplex piston pumps are well known and have been used in the water well drilling industry for many years. Typically they employ a crankshaft and flywheel driven in various ways, a reciprocating engine or a hydraulic motor being examples. Typically, they are heavy units with a large component of cast iron. Today"s well drilling trucks carry lengths of drilling pipe, as well as derricks, motors, pumps of various kinds, and the “mud” pump. The current double acting duplex piston pumps with crankshaft and flywheel, being very heavy, contribute significantly to the weight and space requirements of the truck. They impact the ability of a truck to meet federal highway weight restrictions. Also, the mechanical crank throw design imparts a variable speed to the mud pump piston. In such designs, the piston is either accelerating or decelerating during a large part of its design stroke. So the piston operates at its full design capacity during only a portion of the stroke. Therefore, it is an object of the present invention to provide a duplex piston pump useful as a mud pump on a water well drilling machine, but without a motor, crankshaft, flywheel, gearing, and/or belts, for a significant weight reduction.

Described briefly, according one embodiment of the present invention, a mud pump is provided with two working cylinders for pumping mud, and two sets of double-acting hydraulic driving cylinders. One set of two driving cylinders has the piston of each connected to the piston of one double-acting mud pump cylinder. The other set of two driving cylinders has the piston of each connected to the piston of the other double-acting mud pump cylinder. The connection of a set of driving cylinder pistons to the mud pump piston is through a member which allows side-by-side, or over and under parallel arrangement of the driving cylinders and mud pump cylinders, so the overall length is minimal. An electro-hydraulic control system is provided to coordinate the action of the pump driving cylinders with the mud pumping cylinders for contributing to steady flow of mud from the mud pump.

FIG. 2 is a schematic elevational view of one of the two pump assemblies of the duplex piston pump according to one embodiment of the present invention.

FIG. 3 is a schematic diagram of a system according to the illustrated embodiment and showing both of the duplex mud pump cylinders, with one of two hydraulic driving cylinders for each of the mud pump cylinders, and including an organization of hydraulic flow divider, rod position sensing, proximity-type electrical switches and associated electrical relays for solenoid-operated hydraulic fluid directing spool valves associated with the hydraulic cylinders.

FIG. 6 is an example of a flow chart relating mud pump speed to mud pump output volume capacity and hydraulic driving oil volume requirement for a pump according to the illustrated embodiment of the present invention.

FIG. 7 is a diagram showing theoretical pump driving cylinder piston performance of the two sets of mud pump driving cylinders operating according to the illustrated embodiment of the present invention.

FIG. 1 shows, schematically, a normal environment in which the mud is pumped by duplex piston pump 5 of the present invention from the chip separation tank 6 through the pump and the discharge the line 7 into the top of drill pipe 8 and down in the drill pipe and out into the well casing at the drill bit 10. The mud flows upward through the casing and back into the separation tank 6. The pump itself includes two mud pumping cylinders 1 and 2 fixed relative to a base 3 (FIGS. 5A and 5B) by mounting to four housings 4L, 4F, 4R and 4B which are fixed to the base.

As suggested above, according to the present invention, an all-hydraulic drive for the two mud-pumping pistons in cylinders 1 and 2 is achieved. For that purpose, and referring to FIG. 3, a variable volume hydraulic pump P is used. It can be set, for example, at a rate of 36 gallons per minute at 1,000 psi. A motor M can be used to drive such a pump, and such pumps and drives for them are known in the art and readily available. The pump output is fed to a flow divider D. This is not merely a device to split the flow. Instead, it has a piston inside which will shift in either direction to the extent necessary as it tries to be sure that the exact same volume flow rate is delivered at both output ports of the flow divider. An example of such a flow divider is Model MH2FA by Rexroth Worldwide Hydraulics.

Before proceeding further with this description, it is important to understand that each half of the duplex piston pump includes a double-acting mud pump cylinder and piston assembly. FIG. 2 shows one of the halves including mud pump cylinder 1. The other half, including a mud pump cylinder and associated hydraulic driving cylinders is identical. FIG. 5A shows, schematically, a rod end view of the duplex piston mud pump 5 including the mud pump cylinders 1 and 2 and associated driving cylinders of both halves.

The mud pump cylinders and their associated driving cylinders may be fixed relative to each other and mounted to the base 3 by any suitable means. The schematics of FIGS. 5A and 5B show, as an example, the four valve housings 4F, 4L,4B and 4R fixed to base 3. Except for right and left ports, each of these housings is the same as the others, and includes therein a chamber such as 41C having an opening 41A communicating with a port of a mud pump cylinder such as cylinder 1 or 2. Each chamber 41C also has two other openings. One of them is fitted with a one-way, spring loaded outlet valve such as 16 to enable mud to move from chamber 41C into the upper end of housing 4L and out through port 41D into the discharge plenum 7A. The other opening 41E of chamber 41C is fitted with a spring loaded inlet valve such as 14 communicating with the lower end of housing 4L and enabling mud entering suction inlet 6A of the mud suction manifold 6B to enter through port 41E in housing wall and into chamber 41C. The mud pump cylinders are attached to their respective valve housings in conventional manner with the ports of the cylinders communicating with the respective chambers of the housings.

Referring now to FIGS. 2 and 5A and 5B together, FIG. 2 shows schematically mud pump cylinder 1 and inlet and outlet valves 11 and 12, respectively, associated with the pump port at one end of cylinder 1, and inlet and outlet valves 14 and 16, respectively, associated with the pump port at the opposite end of cylinder 1, the rod-end of the cylinder. In practice since there would normally be only one port at each end of the cylinder, the valves would be in the housings 4L and 4F for cylinder 1. There is a packing gland 17 at the rod-end of the cylinder. In FIG. 5B the top of housing 4L is cut away to show discharge valve 16. Suction or inlet valve 14 below chamber 41C is shown larger in dashed lines to be able to see it in FIG. 5B, as it is the bottom of chamber 41C, FIG. 5A.

According to one feature of this invention, there are two hydraulic driving cylinder/piston assemblies 19 and 21 arranged in a way to drive the mud pump piston 1P in cylinder 1. As suggested above, cylinders 1, 19, and 21 are all connected relative to each other by some suitable means (brackets and/or clamps, for example) so that they are longitudinally immovable relative to one another. This is represented schematically for both sets of mud pump and driving cylinders at the valve housing 4L, 4R and associated inlet and outlet and base in FIGS. 5A and 5B, to which all of the six cylinders of both halves of the duplex pump are rigidly, but removably connected. Each of the two driving cylinder assemblies for piston 1P has a piston rod such as 19R and 21R bolted to a rod connector plate 22. Each rod may extend through the piston and exit the driving cylinder at the end opposite the plate-connected rod end, as indicated at 19S and 21S. The respective pistons 19P and 21P are affixed and sealed to the rod in a suitable way and may be of any suitable construction. Of course, the same effect may be achieved using separate colinear rods secured to opposite faces of the pistons. The piston rods 19R and 21R of the driving cylinders for mud pump cylinder 1, and rod 1R of the mud pump cylinder 1 itself, are bolted to the rod connector plate 22. Each of the rods 19R, 19S and 21R, 21S is supported at opposite ends of the respective cylinder by bearings and seals at 19B and 21B, respectively. Using double rod cylinders provides equal working area on the two sides of the piston, enabling equal oil flow and thrust capacity in both directions of piston travel. One or the other of the driving cylinder rods for mud pump cylinder 1 is associated with a set of proximity sensing switches A-1, B-1, C-1, and D-1 to operate a relay to shift a hydraulic solenoid valve spool to control hydraulic fluid to and from the set of two driving cylinders 19 and 21 to drive the mud pump 1. The same kind of arrangement is provided for mud pump cylinder 2. For each set, the driving cylinder which has the associated proximity switches, may be referred to hereinafter from time-to-time, as the control cylinder.

In this particular arrangement, only as an example of cylinder and rod size, the mud pump cylinder may be six inches in diameter with a twelve inch stroke, using the pistons of two driving cylinders of two inch diameter each to drive the one mud pump piston. A significant advantage can be achieved by making the rods of the driving cylinders larger in diameter (1.375 inches, for example) than that of the mud pump cylinder rod (1.25 inches, for example). It enables use of larger and longer wearing bearings in the driving cylinders, and enables the use of a relatively small piston rod and packing gland 17 in the mud pump cylinder, thus minimizing exposure to wear of the packing gland. The combination of the large diameter rods in the driving cylinders, fixed to a rigid rod connector plate 22 to which the mud pump cylinder rod is bolted, contributes to a very rigid structure. It avoids the necessity of a very long arrangement and long piston rod spans which would be necessary if the mud pump cylinder was driven by a single piston in a hydraulic cylinder on the same longitudinal axis. That would require a more complicated bearing arrangement to support the mud pump cylinder rod. In the present arrangement, the cylinder rod bearings are relatively close to the mud pump packing gland, helping extend the life of the gland by minimizing radial working and resulting loading of the mud pump rod on the packing gland. Also, with the present arrangement, the driving cylinder rods are in tension when the mud pump rod is in compression, which reduces the bending moment.

The proximity sensor switches A-1 through D-1 are responsive to movement of an actuator such as flange 19F on rod 19R, 19S. These switches may be normally-closed or normally-open switches as a matter of convenience in the construction of the circuitry. It should be understood, of course, that the other half of the duplex double acting pump assembly which includes cylinder 2, has driving cylinders such as 29 and 31 associated with it, and proximity switches associated with the piston rod of one (29, for example) of those driving cylinders, (shown in FIGS. 3 and 5A) in the same manner as for the assembly shown in FIG. 2. The position of the piston in cylinder 1 is preferably in a different location and/or it is moving in a different direction, from that of the piston in cylinder 2.

Referring now to FIG. 3, mud pump cylinder 1 and mud pump cylinder 2 are shown schematically, as is one cylinder of each set of two driving cylinders for each of the two mud pump cylinders 1 and 2, respectively. Since the mud pump cylinders are virtually identical and the two driving cylinders of the set for each of the mud pump cylinders are virtually identical, a description of one driving cylinder and associated controls will suffice for both.

The output from flow divider D enters the center input port of a two-position, solenoid-actuated, spring-return hydraulic valve V-1. This valve is electrically coupled to a relay switch R-1 which is bi-stable and electrically coupled to the proximity sensor switch A-1. An example of a suitable relay is No. 700-HJD32Z12 by Allen-Bradley. It is a DPDT latching relay. One switched position of this relay switch R-1 causes the solenoid to be energized to open the valve and supply pressurized oil from valve V-1 through line L-1 to the one end of cylinder 19 and likewise cylinder 21 of FIGS. 2 and 5 to drive the pistons in the direction of the arrow 23. This occurs in both driving cylinders 19 and 21, so rod 13R, being mechanically fixed to the two driving cylinder rods 19R and 21R by rod connector plate 22, is likewise driven in the direction of the arrow 23. When relay R-1 is reset by a signal from another proximity switch which can be recognized upon study of FIGS. 4A through 4D, it de-energizes the solenoid for valve V-1, enabling the spring therein to return the solenoid to position where the supply to the cylinder 19 is through line L-2, to reverse the direction of the piston in that cylinder and its companion driving cylinder, thus reversing the direction of the mud pump piston 1P. Whichever side of the piston is not pressurized at any time is enabled to dump through the valve V-1 to sump S-1. Essentially the same arrangement exists for control and drive of mud pump cylinder 2. In this instance, the proximity switches are designated A-2, B-2, C-2 and D-2. The relay switch is R-2 and the control valve is V-2 operated by a solenoid. It should be mentioned at this point, however, that while the pistons in the driving cylinders for one of the mud pump cylinders are located in the same relationship to each other as the mud pump cylinder with which they are associated, they are typically out of phase with respect to the mud pump piston and pistons of associated drive cylinders of the other mud pump cylinder. This is intentional in an effort to be sure that the flow out of the mud pump assembly 5 is as stable and constant as possible. That is the goal to which the organization of the proximity switches and associated relay switches are directed. Also with reference to FIGS. 2 and 3, it should be mentioned that the supply lines L-1 and L-2 to cylinder 19 are larger than the lines from cylinder 19 to cylinder 21. This is because the lines from valve V-1 go directly to only one of the two driving cylinders and from that point, are directed to the other driving cylinder. Thus, the supply lines L-1 and L-2 must be large enough to drive both driving cylinders 19 and 21 with essentially equal pressure and volume capacity. This is shown schematically in FIG. 2 with lines B-1 and B-2 from cylinder 19 to cylinder 21.

Referring now to FIGS. 4A through 4D, along with FIG. 3, FIG. 4A is a simplified portion of FIG. 3. It includes a driving cylinder 19 for mud pump cylinder 1, and driving cylinder 29 for mud pump cylinder 2. It also shows the proximity switches A-1 and B-1 associated with the piston rod portion 19S of cylinder 19. Similarly, proximity switches A-2 and B-2 associated with the piston rod 29S of driving cylinder 29, are shown. The position of the rod 19S relative to rod 29S is only for purposes of example, as it is not expected that the pistons of cylinders 1 and 2 will ever be positioned at the same longitudinal location relative to each other unless they are passing as one goes in one direction and the other goes in the other direction. But the purposes of the proximity switches A-1 and B-1 is to limit the travel of the piston in the two directions. Thus, either the switch A-1 or the switch B-1 can set or reset relay R-1 to cause the valve V-1 to shift and switch the high pressure from valve V-1 to either line L-1 to move the driving piston and thereby the mud pump piston 1P to the right, or apply the high pressure to line L-2 and drive the driving piston and thereby, the mud pump piston 1P to the left. Regardless of which direction the mud pump piston is moving, it will be drawing mud from the chip separation tank 6 and discharging it to the manifold connected to discharge line 7. The arrangement and operation is true regarding driving cylinder 29 and the proximity switches and relay R-2 and valve V-2 associated with that piston rod 29S.

To assure that the pistons of the two mud pump cylinders are never at either end limit of their strokes simultaneously, two additional proximity switches C-1 and D-1 (FIGS. 4B and 4D) are added. Each of these can be located about 2 inches, for example, from the proximity switches A-1 and B-1 and functions in the same way as described above with respect to switches A-1 and B-1.

The control system of FIG. 4D provides the combination of components to achieve two objectives. The first, and probably the more important, is to insure that the set of power cylinders 19 and 21 for mud pump cylinder No. 1 will cycle independently of the set of power cylinders 29 and 31 for mud pump cylinder 2, providing a 12 inch stroke for each of the mud pump cylinder rods independently of the other rod. A scheme for accomplishing this is shown generally in FIG. 4A where the sensor A-1 or the sensor B-1 can energize the latching relay R-1 at opposite ends of the piston rod stroke.

Another objective is to build a system which will insure that the piston 1P for mud pump cylinder 1 does not reach the end of its individual stroke at the same time as the piston 2P for mud pump cylinder 2. That could occur when both pistons are side-by-side and going in the same direction (FIG. 4B, for example) or when they are phased 180 degrees apart, so going in opposite directions and nearing the ends of their strokes (FIG. 4C, for example). These conditions are more complex and are addressed by the additional components shown in FIGS. 4B and 4C.

In addressing this problem, it should be recognized that the mud pump pistons could arrive at the ends of their strokes at the same time even if not necessarily together mid-stroke, but they would probably have been together at least a short distance before they reached the ends of their strokes. In FIGS. 4B and 4C and the above description, a two inch distance from the end of the stroke is mentioned and shown, but this distance could be one inch or some other suitable distance. If the two pistons are together a short distance from the end of their strokes, it is likely that they would reach the end of their strokes at essentially the same time.

Since reaching the end of the stroke simultaneously for both mud pump pistons is not desirable, the present invention reverses one of the two pistons prior to reaching the normal end of the stroke. When one piston reverses, its stroke has been limited at 10 inches. This will place the two mud pump pistons out of phase for an extended period. For this purpose, the additional proximity switches C-1 and D-1 for piston rod 19S, and C-2 and D-2 for piston rod 29S, are added, as mentioned above. For the right combination of signals, to correctly use the proximity switches C-1, C-2, D-1 and D-2, additional relays R-3, R-4, R-5 and R-6 can be used. An example is a DP/DT, a stable (non-latching) relay by Siemens, Potter & Brumfield Division.

The combination of the foregoing components for the control functions as described above and shown in FIGS. 4A, 4B and 4C, results in the control component organization of FIG. 4D which is a consolidation of the systems of FIGS. 4A, 4B and 4C, to achieve the above-mentioned goals of having the power cylinder set for mud pump cylinder 1, cycle independently of the power cylinder set for mud pump cylinder 2, and avoiding the simultaneous arrival at the end of their strokes of mud pump piston 1 and mud pump piston 2. At this point it should be understood that specific implementation of controls is not limited to the above-described organization of proximity switches, activators for them, types of valves or relays, whether electrically or pneumatically controlled, or the specific organization of an electrical, pneumatic, or optical control circuit, for example, portions of which may be solid state discrete devices, or integrated circuit organizations, as it will depend largely on the preference of and choices by a control circuit designer and well within the skill of the art of one who understands the organization and intentions and implementation described above, according to the present invention.

Initially, in the practice of the present invention according to the illustrated embodiment, it is intended that valving and control as shown in FIG. 4D and described above, or in such other scheme as may be preferred, be used so that when a constant flow of hydraulic oil is delivered into the system by the hydraulic pump P, relatively constant mud flow from the double acting duplex mud pump will be possible. With the present invention, the flow divider D (FIG. 1) is truly a flow divider, attempting to deliver the same volume at both outlet ports. To do so, it attempts to adapt to any difference in operation of one of the mud pump pistons relative to the other, by adjusting the pressure. For example, if the piston rod packing in one mud pump cylinder is tighter on the rod than on the other mud pump cylinder, the flow divider spool centering springs will tend to move the spool in a direction attempting to establish the same amount of flow to both of the hydraulic oil driving cylinders. Also, when one mud pump driving cylinder set piston reaches the end of its stroke, what would otherwise appear to be a sharp rise in pressure to be handled by the flow divider, can be tolerated by the flow divider itself so as to avoid damaging mechanical or hydraulic shock. This effect is somewhat mirrored in FIG. 7 which shows in the solid lines, the wave form of pressure available from the mud pump cylinder 1 for one stroke cycle, that being a full stroke from left to right, and a full return stroke from right to left in FIG. 3, for example. The dashed wave form represents the available pressure from mud pump cylinder No. 2. In this illustration, the discharge pressure in cylinder 1 begins a sharp rise from 0 at point A to a maximum available pressure at point M and then drops sharply beginning at point N to 0 at point R. Then it rises on the opposite side of the piston sharply at point R to the same maximum level and then drops again to 0 at point S. Meanwhile, if the pistons of the two mud pump cylinders happen to be operating at 90° phase relationship, the available pressure from the cylinder No. 2 follows the dashed line. Both of these pressure “curves” are essentially a square wave, in contrast to the somewhat sinusoidal output of a conventional, crankshaft-driven duplex piston pump. At point A, when the pistons in the driving cylinders for cylinder 1 get to the end of their stroke, the hydraulic pressure on the driving pistons rises sharply until the pistons begin moving in the opposite direction. This is because of the fact that, when the pistons of either driving cylinder set reach the end of their stroke, and the related solenoid valve is shifting to change the direction of the piston, there is no flow of oil through this valve. With a constant input flow of oil, it must be re-routed to prevent pressure build-up in the system and popping pressure relief valve, and also to prevent a volume drop in the discharge of the mud pump. The flow divider D has tolerance to enable this temporary re-routing to the driving cylinders 29 and 31. At the same time, with the additional pressure on these cylinders driving pump 2, a pressure spike may result in mud pump cylinder 2 such as shown in the dashed line at A and R and S in FIG. 7. The spike could be at other locations, depending upon the phase relationship of the cylinder set for mud pump cylinder 1 and the cylinder set for mud pump cylinder 2. Thus with a less than 100% accuracy-style flow divider D, the excess oil from one shifting solenoid valve is routed to the other (open) solenoid valve and driving cylinder set, which increases in speed and keeps the mud pump discharge constant. The oil itself becomes an accumulator and pressure relief system, operating at the exact same pressure over the full range of the operating system and produces the effect of constant velocity pistons in the mud pump.

Since these driving pistons are not driven by a crank shaft, they operate at essentially constant velocity. In other words, whereas a piston driven by a rotating crank shaft moves according to a harmonic sine wave pattern, a piston driven according to the present invention defines essentially a square wave pattern. In a conventional pump where the piston is driven by a rotating crank shaft, the inlet and outlet valves must be designed and sized to permit maximum flow, which typically occurs at the time of maximum travel of the piston, which occurs when the crank pin axis and rotational axis of the crank shaft are in a plane perpendicular to the axis of the piston. In contrast with construction according to the present invention, the inlet and outlet valves are sized to a maximum flow which is essentially constant regardless of where the piston is during its stroke, and which is only limited by the flow available from the flow divider. Therefore, as an example, where a conventional 5×6 mechanically driven pump using 5×6 valves, would handle about 150 gallons per minute, a pump according to the present invention with a 5″ diameter bore and 6″ stroke could be expected to produce on the order of 300 gallons per minute although using the same size “5×6” valves. Accordingly, the present invention provides the possibility of approximately twice the volume capacity with significantly less space and weight by virtue of the essentially constant velocity pistons, and significantly less overall length.

Referring again to FIG. 3, with the pump P delivering 36 gallons per minute, for example, the flow divider delivers approximately 18 gallons per minute through each output port, and which is delivered to the hydraulic driving cylinders. It should be understood that pumps having other capabilities in terms of volume and pressure can be employed. The 36 gallon per minute number is selected to match one combination of pump valves and suction hose size. Other combinations can be made for other sizes of suction hose, valves, and operating speeds, and are within the skill of the art. If there is no imbalance in the loads on the pistons of these sets of hydraulic cylinders, each of them can move at the rate determined by 18 gallons per minute flow into the cylinder at 1,000 psi (ignoring friction losses in the lines).

Because of the relative differences in sizes of the driving cylinders and the mud pump cylinders, and again, ignoring friction losses, the mud pump cylinders will be able to deliver 100 gallons per minute at 200 psi.

As suggested above, in the practice of the present invention, the oil of the piston pump system is used to absorb the undesirable pressure peaks of the primary hydraulic system. Resistance of the mud pump hydraulic system can offset the inertia of the traveling pistons and the piston rods when they reach the end of their stroke. The problem of moving excess oil during the time the valve spools are shifting, is addressed to avoid pressure peaks and consequent opening of the relief valves on each stroke. This problem of moving excess oil is solved by using an open system between the two sets of driving pistons. When the control valves close to change the direction of one set of pistons, the oil is free to flow to the other set of pistons which may be in the middle of their stroke operating at the same pressure. The volume of liquid lost in one mud pump cylinder is made up by the increase in the other, insuring that the mud pump discharge remains constant.

The pressurized side of a hydraulic cylinder is free to accelerate, based on the flow of oil being supplied. But the suction side of a mud pump piston has additional forces. Such piston velocity can only accelerate at a rate based on the flow of liquid moving through the suction valve. When a force is applied to increase the piston to a speed exceeding the incoming flow, increased vacuum forces or cavitation develops and the mud pump cylinder walls tend to deteriorate. Using an open-type system according to the present invention, some portion of supplied driving oil is free to move from the driving cylinder set for the starving cylinder through the flow divider to the driving cylinder set, reducing the acceleration rate and damage to the starving mud pump cylinder walls. Thus in the present invention, the primary hydraulic system can constructively interact with pressures of the secondary, mud management system.

In the water well drilling field, the application of a mud pump requires it to operate from zero to maximum pressure and zero to maximum flow as the drilling proceeds. This eliminates the opportunity to use standard accumulators and limit switches, as such devices must always be preset or designed for a given pressure. By using the open-to-atmosphere concept in the present invention, one of the two hydraulic piston sets is always working against the pressure developed by the resistance of the liquid (mud) being pumped. This liquid thus serves as an accumulator which is always working at the exact pressure required. Since the pressure is a function of the resistance of the fluid and the atmosphere, no relief valve is required.

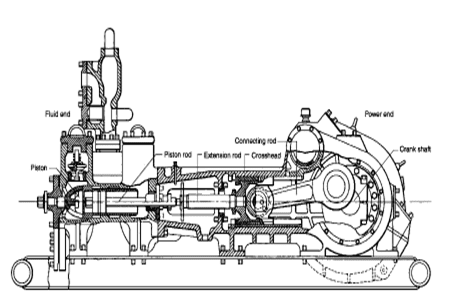

While, the hydraulic driving cylinders are shown on top and bottom of a mud pump cylinder, other embodiments of the invention might have them beside or otherwise related to the mud pump cylinder as long as the piston rods of the hydraulic cylinders are somehow connected to the piston rod of the mud pump cylinder, so as to drive the mud pump piston. Also, some inventive aspects can be implemented with only a single hydraulic power cylinder for each mud pump cylinder, but using the accommodating flow divider and valve control system disclosed herein. While it is possible to make the cylinders the movable components, and other mixes and mechanical arrangements of rods and cylinders are possible, it is believed that making the rods the movable components simplifies the organization. In summary, the introduction of hydraulic power cylinders into a mud pump according to the present invention, eliminates the use of the complete power end (crankshaft, flywheel, etc.) of a conventional mechanically powered mud pump. Instead the cylinder power source provides a relatively constant velocity piston to move fluid at the piston"s rated flow essentially the full length of its design stroke. This permits a pump design with much smaller operating valves than would otherwise be required for the capacity required, contributing to a much smaller unit in size and weight.

8613371530291

8613371530291