overshot jaw dog free sample

You can use this royalty-free photo "Small dog with undershot jaw posing indoors" for personal and commercial purposes according to the Standard or Extended License. The Standard License covers most use cases, including advertising, UI designs, and product packaging, and allows up to 500,000 print copies. The Extended License permits all use cases under the Standard License with unlimited print rights and allows you to use the downloaded stock images for merchandise, product resale, or free distribution.

You can use this royalty-free photo "Black and tan mixed breed dog with undershot jaw" for personal and commercial purposes according to the Standard or Extended License. The Standard License covers most use cases, including advertising, UI designs, and product packaging, and allows up to 500,000 print copies. The Extended License permits all use cases under the Standard License with unlimited print rights and allows you to use the downloaded stock images for merchandise, product resale, or free distribution.

You can download this article on puppy teeth problems as an ebook free of charge (and no email required) through the link below. This comprehensive article covers such topics as malocclusions, overbites, underbites and base narrow canines in dogs. Special emphasis is placed on early intervention – a simple procedure such as removing retained puppy teeth can save many problems later on.

One of the biggest misconceptions is that dental problems don’t need the same treatment in animals as they do in humans. Nothing could be further from the truth! Dogs’ teeth have the same type of nerve supply in their teeth as we do, so anything that hurts us will hurt them as well.

All dogs, whether they are performance dogs or pets, deserve to have a healthy, pain-free mouth. Oral and dental issues frequently go undiagnosed in dogs, partly because the disease is hidden deep inside the mouth, and partly because dogs are so adept at hiding any signs of pain. As a pack animal, they don’t want to let the rest of the pack (including us!) know they have a problem, as anything that limits their usefulness to the pack may be grounds for exclusion. This is a survival instinct. Dogs will suffer in silence for as long as they can, and they only stop eating when they cannot bear the pain any longer.

This article has been written to help you understand how oral and dental problems develop in puppies, what the implications of these issues are, and what options are available to you and your pup to achieve the best outcomes in terms of overall health, comfort and performance. You don’t need to read it from top to bottom, as your dog would need to be pretty unlucky to need all the advice included here!

If you would like to speak to me for advice on your dog, please feel very welcome to call me on 1300 838 336, or you can email me on support@ sydneypetdentistry.com.au.

baby) teeth which erupt between 3-8 weeks of age. These are replaced by the adult (permanent) teeth between 4-7 months of age. Adult dogs should have a total of 42 teeth. The difference in the number of deciduous and adult teeth arises because some adult teeth (the molars and first premolars) don’t have a deciduous version.

The ‘carnassial’ teeth are the large specialised pair of teeth towards the back of the mouth on each side, which work together like the blades of a pair of scissors. The upper carnassial is the fourth premolar, while the lower one is the first molar The upper jaw is the maxilla, and the lower jaw is the mandible.

The bulk of the tooth is made up of dentine (or dentin), a hard bony-like material with tiny dentinal tubules (pores) running from the inside to the outside. In puppies, the dentine is relatively thin, making the tooth more fragile than in an older dog. The dentine thickens as the tooth matures throughout life.

Malocclusion is the termed used for an abnormal bite. This can arise when there are abnormalities in tooth position, jaw length, or both. The simplest form of malocclusion is when there are rotated or crowded teeth. These are most frequently seen in breeds with shortened muzzles, where 42 teeth need to be squeezed into their relatively smaller jaws. Affected teeth are prone to periodontal disease (inflammation of the tissues supporting the teeth, including the gums and jawbone), and early tooth loss.

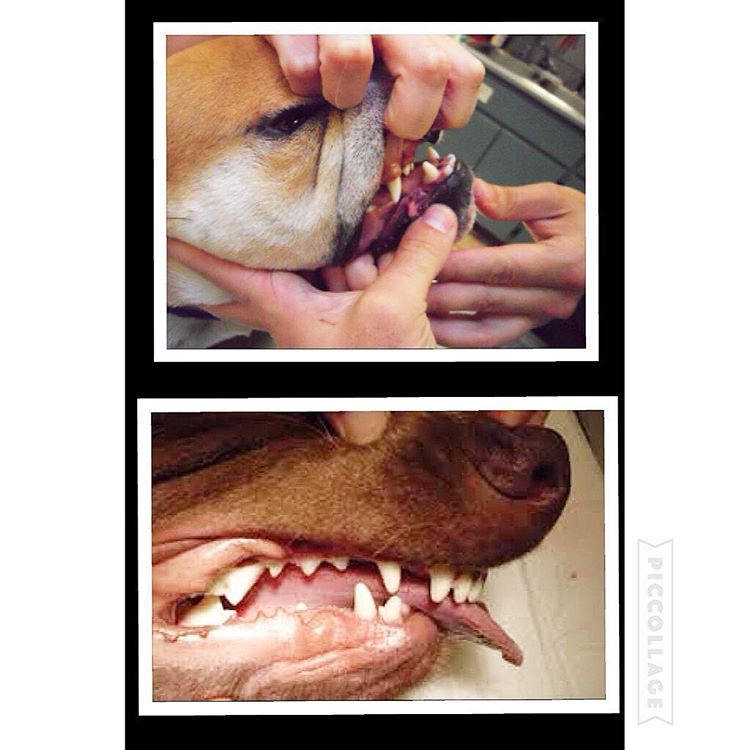

Crowded upper incisor teeth in an English Bulldog, with trapping of food and debris. There is an extra incisor present which is exacerbating the problem.

‘Base narrow’ canines (Linguoverted or ‘inverted’ canines) are a relatively common and painful problem in Australian dogs. The lower canines erupt more vertically or ‘straight’ than normal (instead of being tilted outwards), and strike the roof of the mouth. This causes pain whenever the dog chews or closes its mouth, and can result in deep punctures through the palatal tissues (sometimes the teeth even penetrate into the nasal cavity!). In our practice in Sydney, we see this most commonly in Staffordshire Bull Terriers and Labrador Retrievers.

Lance’ canines (Mesioverted, hard or ‘spear’ canines) occur when an upper canine erupts so it is pointing forward, like a tusk. This is seen most commonly in Shetland Sheepdogs, and can lead to lip trauma and displacement of the lower canine tooth (which cannot erupt to sit in its normal position in front of the upper canine).

Class II malocclusions (‘overshot’) arise when the lower jaw is relatively short compared with the upper jaw. This type of occlusion is NEVER considered normal and can result in significant and painful trauma to the upper gums, hard palate and teeth from the lower canines and incisors.

Class III malocclusions (‘undershot’, ‘prognathism’) occur when the lower jaw is relatively long compared with the upper jaw. The upper incisors may either meet the lower ones (level bite) or sit behind them (reverse scissor bite). While this is very common, and considered normal for some breeds, it can cause problems if the upper incisors are hitting the floor of the mouth or the lower teeth (similar problems to rostral crossbite). If the lower canines are striking the upper incisors, the accelerated dental wear often results in dead or broken teeth.

Class IV malocclusions (‘wry bite’) occur when there is a deviation of one or both jaws in any direction (up and down, side to side or front to back). These may be associated with mild to severe problems with chewing, damage to teeth and oral tissues, and chronic pain.

Normal development of the teeth and jaws is largely under genetic control, however environmental forces such as nutrition, trauma, dental interlock and other mechanical forces can also affect the final outcome.

Most malocclusions involving jaw length (skeletal) abnormalities are genetic in origin. We need to recognise this as it has enormous implications if you are planning to breed, as once a malocclusion is established in a line, it can be heartbreaking work to try and breed it back out.

The exact genes involved in jaw development are not yet well understood. We do know that the upper and lower jaws grow at different rates, at different times, and are under separate genetic control. In fact, the growth of one only affects the growth of the other if there is physical contact between them via the teeth. This contact is called ‘dental interlock’.

When the upper and lower teeth are locked against each other, the independent growth of either jaw is severely limited. This can occasionally work in the dog’s favour, for example if the lower jaw is slightly long compared with the upper jaw, the corner incisors may lock the lower canines in position behind them, limiting any further growth spurts of the lower jaw.

However, in many cases, dental interlock interferes with jaw development in a negative way. A classic example we see regularly in our practice is when a young puppy has a class II malocclusion (relatively short lower jaw) and the lower deciduous canines are locked behind the upper deciduous canines, or trapped in the tissues of the hard palate. In these cases, even if the lower jaw was genetically programmed to catch up to the upper jaw, it cannot physically do so.

Extraction of these teeth will not stimulate jaw growth, but will allow it to occur if nature (ie genetic potential) permits. It also relieves the painful trauma caused by the teeth to the hard palate whenever the pup closes its mouth (and we all know how sharp those baby teeth are!!). More information on interceptive orthodontics can be found later in this book.

Although diet often gets the blame for development of malocclusions, the role of nutrition is actually much less significant than is often believed. Obviously gross dietary deficiencies will affect bone and tooth development, for example severe calcium deficiency can lead to ‘rubber jaw’. However, the vast majority of puppies are on balanced, complete diets and have adequate nutrient intake for normal bone and tooth development.

One myth I have heard repeated by several owners is that strict limitation of a puppy’s dietary intake can be used to correct an undershot jaw. This is simply NOT true. Limiting calories will NOT slow the growth of the lower jaw relative to the upper jaw (both jaws receive the same nutrient supply). Such a practice is not only ineffective, it can be detrimental for the puppy’s overall growth and development.

Trauma, infection and other mechanical forces may affect growth and development of the jaws and teeth. Developing tooth buds are highly sensitive to inflammation and infection, and malformed teeth may erupt into abnormal positions (or not erupt at all!). Damage to developing teeth can also occur if the jaw is fractured.

Retained or persistent deciduous (puppy) teeth can also cause malocclusions by forcing the erupting adult teeth into an abnormal position. As previously mentioned, this may be a genetic trait, but can also occur sporadically in any breed of dog.

The basic rule is that every dog deserves a pain-free, functional mouth. If there is damage occurring to teeth, or oral tissues, we need to alleviate this, to allow the dog to live happily and healthily. If there is no functional problem and no trauma occurring, then treatment is simply not required.

Sometimes the hardest part is determining whether the problem is in fact causing pain. As we know, dogs are very adept at masking signs of oral pain, and will and will continue to eat despite real pain. Puppies, in particular, don’t know any better if they have had pain since their teeth first erupted very early in life.

The overriding aim is always to give the dog a healthy, pain-free and functional mouth. Sometimes this will result in a ‘normal’ mouth, whereas in other cases, this might not be realistically achievable.

While some basic advantages and disadvantages of the different treatment options are outlined here, it is very important to seek specific advice for your individual dog, as no two mouths are exactly the same, and an individual bite assessment will help us determine the best course of action together. You can contact us anytime.

Extraction of lower canine teeth – the roots of these teeth make up about 70% of the front of the jaw, and so there is a potential risk of jaw fracture associated with their removal. Some dogs also use these teeth to keep the tongue in position, so the tongue may hang out after extraction.

Crown reduction is commonly performed to treat base narrow canines, or class II malocclusions, where the lower canines are puncturing the hard palate. Part of the tooth is surgically amputated, a dressing inside the tooth to promote healing and the tooth is sealed with a white filling (just like the ones human dentists use). This procedure MUST be performed under controlled conditions as it exposes the highly sensitive pulp tissue. If performed incorrectly, the pulp will become infected and extremely painful for the rest of the dog’s life.

While the dog may lose some function, this is far preferable to doing nothing (this condemns the dog to a life of pain). Indeed, unless released into the wild, dogs do well even if we need to extract major teeth (canines and carnassials), as they have the humans in their pack to do all the hunting and protecting for them.

This is the term we use when we remove deciduous teeth to alter the development of a malocclusion. The most common form of this is when we relieve dental interlock that is restricting normal jaw development. Such intervention does not make the jaw grow faster, but will allow it to develop to its genetic potential by removing the mechanical obstruction.

Extraction of deciduous lower canines and incisors in a puppy with an overbite releases the dental interlock and gives the lower jaw the time to ‘catch up’ (if genetically possible).

As jaw growth is rapid in the first few months of life, it is critical to have any issues assessed and addressed as soon as they are noticed, to give the most time for any potential corrective growth to occur before the adult teeth erupt and dental interlock potentially redevelops. Ideally treatment is performed from eight weeks of age.

Extraction of deciduous teeth is not necessarily as easy as many people imagine. These teeth are very thin-walled and fragile, with long narrow roots extending deep into the jaw. The developing adult tooth bud is sitting right near the root, and can be easily damaged. High detail intraoral (dental) xrays can help us locate these tooth buds, so we can reduce the risk of permanent trauma to them. Under no circumstances should these teeth be snapped or clipped off as this is not only inhumane, but likely to cause serious infection and ongoing problems below the surface.

The aim of any veterinary procedure should always be to improve the welfare of the patient, so the invasiveness of any treatment needs to be weighed up against the likely benefits to the dog. Every animal deserves a functional, comfortable bite, but not necessarily a perfect one. Indeed, some malocclusions (particularly those involving skeletal abnormalities) can be difficult to correct entirely.

In addition to the welfare of the individual dog, both veterinarians and breeders need to consider the overall genetic health of the breed. Both the Australian National Kennel Club and (in New South Wales where our practice is situated) the Veterinary Practitioners’ Board stress that alteration of animals to conceal genetic defects for the purpose of improving their value for showing (and breeding) is not ethical.

The bottom line is that, while all dogs will have multiple treatment options available, and in some cases the occlusion can be corrected to the point of being ‘good for show’, advice should definitely be sought about the likelihood of a genetic component prior to embarking upon this, as the consequences for the breed can be devastating if such animals (or their close relatives) become popular sires or dams.

Sometimes a tooth is congenitally missing, that is it has never developed. While dogs can physically cope well with missing teeth, in some breeds this is considered a serious fault, and will severely affect the chances of the dog being successful in the show ring.

Sometimes, the tooth will be in a favourable position but caught behind a small rim of jawbone – again early surgical intervention may be successful in relieving this obstruction. If the tooth is in an abnormal position or deformed, it may be unable to erupt even with timely surgery.

Impacted or embedded teeth should be removed if they are unable to erupt with assistance. If left in the jaw, a dentigerous cyst may form around the tooth. These can be very destructive as they expand and destroy the jawbone and surrounding teeth. Occasionally these cysts may also undergo malignant transformation (ie develop into cancer).

Firstly, if there are two teeth in one socket (deciduous and adult), the surrounding gum cannot form a proper seal between these teeth, leaving a leaky pathway for oral bacteria to spread straight down the roots of the teeth into the jawbone. Trapping of plaque, food and debris between the teeth also promotes accelerated periodontal disease. This not only causes discomfort and puts the adult tooth at risk of early loss, but allows infection to enter the bloodstream and affect the rest of the body.

Broken teeth also become infected, with bacteria from the mouth gaining free passage through the exposed pulp chamber inside the tooth, deep into the underlying jawbone. This is not only painful, but can lead to irreversible damage to the developing adult tooth bud, which may range from defects in the enamel (discoloured patches on the tooth) through to arrested development and inability to erupt. The infection can also spread through the bloodstream to the rest of the body. Waiting for the teeth to fall out is NOT a good option!

We cannot rely on dogs to tell us when they have oral pain. It is up to us to be vigilant and watch for signs of developing problems. Train your pup to allow handling and examination of the mouth from an early age. We will be posting some videos of oral examination tips shortly, watch out in your email inbox for this. Things can change quickly – check their teeth and bite formation frequently as they grow.

Remember, early recognition and treatment is crucial if we want to keep your dog happy and healthy in and out of the show ring. The sooner we treat dental problems, the higher the chance of getting the best possible results with the least invasive treatment.

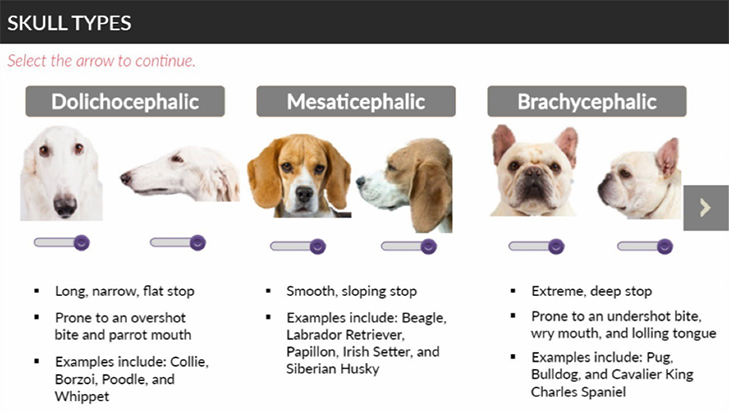

Occlusion is defined as the relationship between the teeth of the maxilla (upper jaw) and mandibles (lower jaw). When this relationship is abnormal a malocclusion results and is also called an abnormal bite or an overbite in dogs and cats.

The mouth is split into quadrants: left maxilla, right maxilla, left mandible and right mandible. Each quadrant of the mouth in both dogs and cats contains incisors (I), canines (C), premolars (PM) and molars (M).

In the normal, aligned mouth, the left and right side mirror each other. Dogs have a total of 42 adult teeth and cats have 30 adult teeth. The normal occlusion of a dog and cat mouth are similar. Below we"ll share how malocclusions can affect both canines and felines.

Class III malocclusions are considered underbites in dogs and cats; the mandibles are longer in respect to their normal relationship to the maxilla. Class III malocclusions are commonly seen in brachycephalic dogs (boxers, pugs, boston terriers, etc).

While cats do not get malocclusions nearly as frequently as dogs, they are not free from this problem. When present, felines malocclusions tend to be more severe and can cause more problems. There is a definitely a breed predisposition for cats with malocclusions. Persians and Himalayan cats tend to have a higher incidence of malocclusions, most frequently underbites.

Just as with dogs, cats with malocclusions should always be evaluated by a veterinarian and treated if their bite is traumatic and causing them pain. Malocclusions are frequently diagnosed in kittens. These abnormal bites are often painful and the sooner they are treated, the better the prognosis for gaining a pain-free and functional bite.

This question, posed to me by a fellow passenger on my return flight from a veterinary conference, caused me to put my current task (subject-tagging images of dogs" and cats" mouths on my computer) on pause. I explained that in cats and dogs, the goal of orthodontic correction isn"t a pretty smile but pain-free, functional occlusion.

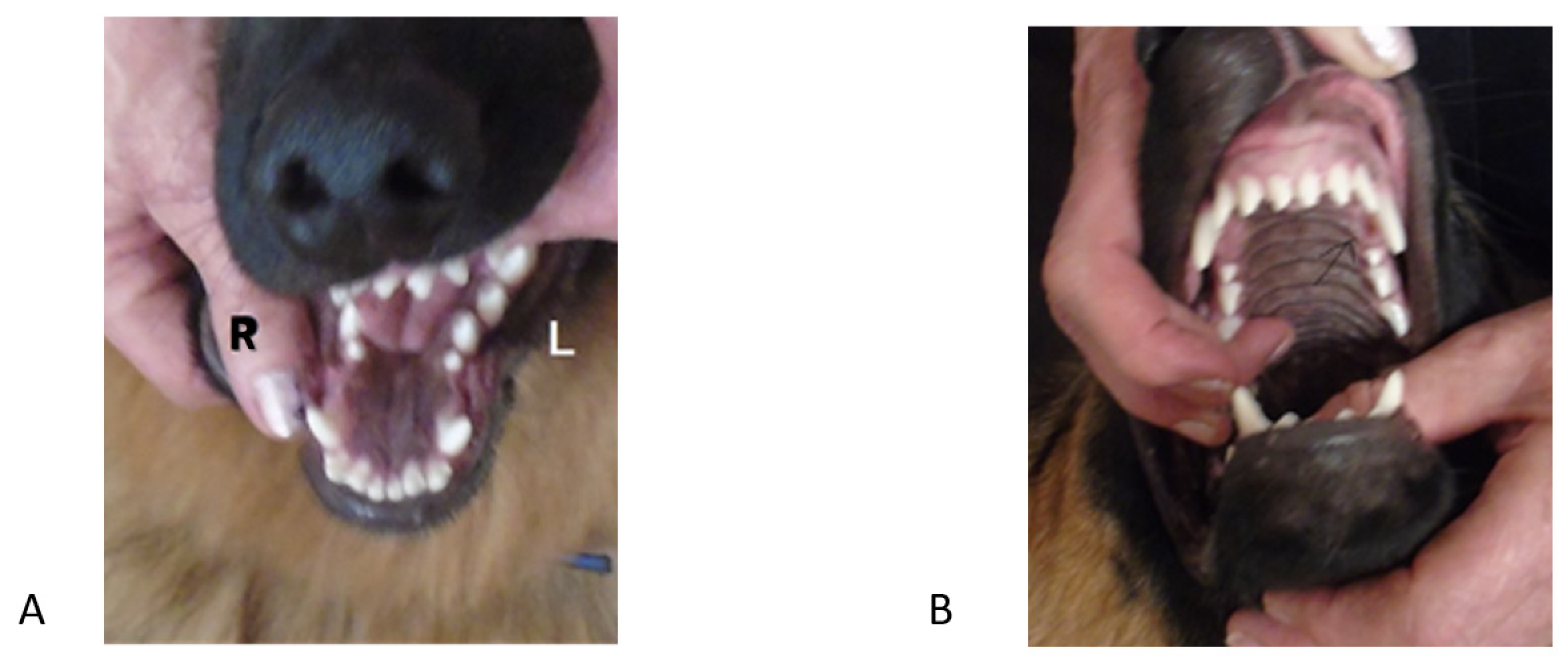

Occlusion refers to the relationship between the maxillary and mandibular teeth when they approach each other, as occurs during chewing or rest. Normal occlusion exists when the maxillary incisors just overlap the mandibular incisors (Figure 1A), the mandibular canines are equidistant from the maxillary third incisors and the maxillary canine teeth, and the premolar crown tips of the lower jaw point between the spaces of the upper jaw teeth in a saw-toothed fashion (Figure 1B). Flat-faced breeds, such as boxers, shih tzus, Boston terriers, Lhasa apsos and Persian cats, have abnormal bites that are recognized as normal for their breed in which the mandibular jaw protrudes in front of the maxillary jaw, altering the above tooth-to-tooth relationship (Figures 2A and 2B).

Malocclusion refers to abnormal tooth alignment. Skeletal malocclusion occurs when jaw anomalies result in abnormal jaw alignment that causes the teeth to be out of normal orientation. Dental malposition occurs when jaw alignment is normal but one or more teeth are out of normal orientation.

Mandibular distoclusion (also called overbite, overjet, overshot, class 2, and mandibular brachygnathism) occurs when the lower jaw is shorter that the upper and there"s a space between the upper and lower incisors when the mouth is closed. The upper premolars will be displaced rostrally (toward the nose) compared with the lower premolars. Mandibular distoclusion is never normal in any breed (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3B. A dog"s mandibular distocluson.Mandibular mesioclusion (also called underbite, undershot, reverse scissor bite, prognathism, and class 3) occurs when the lower teeth protrude in front of the upper teeth. If the upper and lower incisor teeth meet each other edge to edge, the occlusion is an even or a level bite (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Mandibular mesioclusion in a dog.Maxillary mandibular asymmetry (also called wry bite, especially by breeders) is a skeletal malocclusion in which one side of the jaw grows differently from the other side (Figures 5A and 5B).

By the early 1950"s, Lloyd C. Brackett had become a legend in his own time. In part because of the quality of the dogs he produced and in part because of his candor when addressing problems related to the breeding of canines. He had much to say about the selection of sires, how to correct problems and how to make improvements. Brackett was considered one of the fathers of the German Shepherd breed in the United States. At the time of his death he was the oldest living continuos fancier of the breed (since 1912). His kennel was called Long Worth and he is remembered throughout the dog world for his theories about breeding methods. Brackett was well read and a quick learner. Through his writings he shed light on the confusion and misunderstandings associated with line and inbreeding. One of his greatest achievements was to have produced over 90 champions in twelve years.

Brackett understood the value of using quality dogs that were related to each other. This approach allowed him to concentrate the genes needed to produce desired traits. His techniques for reducing error and improving quality focused on the careful selection of breeding partners. They were central to maintaining and improving specific traits while at the same time reducing disease and other unwanted problems. Brackett became famous for breeding quality dogs with consistent type. His strategy relied on a series of breedings using relatives. Often times he was quoted as saying, "never outcross when things seem to be going well, do it only as an experiment or when some fault or faults cannot be eliminated". He was careful to study each stud dog and their offspring, eliminating those who did not measure up and those who produced faults. Close inspection of his pedigrees show that many of his sires were themselves inbred or line bred and most were usually related in some way to the bitches in his breeding program. Brackett"s success helped to make line breeding popular. He demonstrated how to make improvements by retaining a common pool of genes through the use of related dogs. He believed that out-crossing was the least desirable method because it introduced new genes into his pedigrees, which in turn produced differences and genetic variations among the offspring.

Brackett was usually quick to comment on what he observed and how things could be improved. In a statement taken from one of his articles, he said, "whenever two or three dog fanciers get together there is almost sure to be talk about linebreeding. The term may be used without anyone of them having a real understanding of what it means. There seems to be much confusion even in the minds of experienced dog breeders about the actual meaning of the terms and how to differentiate between them". He referred to this dilemma in several articles in a variety of scenarios. He once raised several questions when he heard two breeders discussing a line breeding. He referred to the breeder who recommended it with the statement, linebred to what? He knew that the answer to the question would be a measure of what the breeder actually knew about the term. It was his way of evaluating the wisdom of others. He knew that line breeding can mean many things. For example, a dog can be line bred on its sire"s side of the pedigree or on its dam"s side. Those who use the term usually understand it to mean only that the dogs are related to each other.

Brackett was concerned about the future of breeding better dogs and the lack of breeder education programs. He believed that "the majority of dog breeders formulate no breeding plan and seldom if ever, when making a mating consider how or what they will mate any of the resultant progeny."

The formula Brackett preferred concentrated genes in a pedigree. He did this by placing emphasis on the sire of the sire. In Figure 1, notice that the same dog appears on the sire and the dam"s side of the pedigree. Brackett liked to use one important dog and have it appear twice in a three-generation pedigree. The basic formula he preferred can be stated as follows, "Let the sire of the sire become the grand sire on the dam"s side". Said another way, "let the father"s father become the mothers grandfather".

The sire that is circled appears on both sides of the pedigree. Because it is the same dog it must be an outstanding dog free of disease because his genes are being preserved on both sides of the pedigree and carried forward to the new stud dog.

Brackett knew that Mendel was able to consistently predict the traits in his offspring especially when he knew what characteristics were carried in the pedigrees of the parents. They both knew that when two individuals with known ancestry are bred there is more certainty about what they are likely to produce then when there is missing information about them. Mendel demonstrated these principles in the 1860"s. Brackett used these ideas because he knew that the unexpected is more likely to occur when there are gaps in information about the ancestors and their littermates. While heredity has the tendency to produce resemblance"s, the science of genetics teaches us to search beneath the superficial resemblances of the phenotypes for the important clues in the genotypes. Thus, when an individual is said to be dominant for a trait, it should be taken to mean that a large percentage of their offspring were observed to have a certain trait. It does not mean that all of their offspring will have that trait. Figure 2 illustrates how Brackett would approach breeding a hypotical bitch called "A". The Stick Dog Color Chart pedigree described in Battaglia"s book, Breeding Better Dogs is used to illustrate Brackett"s approach. The stick dog pedigree illustrates how the strengths, weaknesses and trends in a pedigree can be recorded and then easily coded. Notice that each stick figure is drawn with seven structural parts. Using the breed standard each of the seven structural parts are color coded to show there quality or lack thereof. The color-codes for quality:

It must be remembered that the value of a bitch must also be determined by what she has produced. The breeder"s notes about her pups might read: “Her first breeding was to a quality dog with an open pedigree. All four of her pups were of poor quality, one had a disqualifying color; two others had an undershot jaw, one was dysplastic. Her second breeding was a line breeding to another quality dog. This dog was related to her sire. Two of eight pups died of heart disease, one was diagnosed with clinical hip dysplasia, and two others had missing pre molars“. The summary notes about bitch "A" are useful because they present an overview of the bitches qualities.

Note 1.First breeding, N=4, to a sire with an open pedigree. Pups produced: 1 with a white coat, 2 with undershot jaws, 1 dysplastic, and 4 of poor quality

The American Pit Bull Terrier is a medium-sized, solidly built, short-coated dog with smooth, well-defined musculature. This breed is both powerful and athletic. The body is just slightly longer than tall, but bitches may be somewhat longer in body than dogs. The length of the front leg (measured from point of elbow to the ground) is approximately equal to one-half of the dog’s height at the withers.

Above all else, the APBT must have the functional capability to be a catch dog that can hold, wrestle (push and pull), and breathe easily while doing its job. Balance and harmony of all parts are critical components of breed type.

The essential characteristics of the American Pit Bull Terrier are strength, confidence, and zest for life. This breed is eager to please and brimming over with enthusiasm. APBTs make excellent family companions and have always been noted for their love of children. Because most APBTs exhibit some level of dog aggression and because of its powerful physique, the APBT requires an owner who will carefully socialize and obedience train the dog. The breed’s natural agility makes it one of the most capable canine climbers so good fencing is a must for this breed. The APBT is not the best choice for a guard dog since they are extremely friendly, even with strangers. Aggressive behavior toward humans is uncharacteristic of the breed and highly undesirable. This breed does very well in performance events because of its high level of intelligence and its willingness to work.

The skull is large, flat or slightly rounded, deep, and broad between the ears. Viewed from the top, the skull tapers just slightly toward the stop. There is a deep median furrow that diminishes in depth from the stop to the occiput. Cheek muscles are prominent but free of wrinkles. When the dog is concentrating, wrinkles form on the forehead, which give the APBT his unique expression.

The muzzle is broad and deep with a very slight taper from the stop to the nose, and a slight falling away under the eyes. The length of muzzle is shorter than the length of skull, with a ratio of approximately 2:3. The topline of the muzzle is straight. The lower jaw is well developed, wide and deep. Lips are clean and tight.

Serious Faults: Undershot, or overshot bite; wry mouth; missing teeth (this does not apply to teeth that have been lost or removed by a veterinarian).

The tail is set on as a natural extension of the topline, and tapers to a point. When the dog is relaxed, the tail is carried low and extends approximately to the hock. When the dog is moving, the tail is carried level with the backline. When the dog is excited, the tail may be carried in a raised, upright position (challenge tail), but never curled over the back (gay tail).

The American Pit Bull Terrier must be both powerful and agile; overall balance and the correct proportion of weight to height, therefore, is far more important than the dog’s actual weight and/or height.

It is important to note that dogs over or under these weight and height ranges are not to be penalized unless they are disproportionately massive or rangy.

Very Serious Fault: Excessively large or overly massive dogs and dogs with a height and/or weight so far from what is desired as to compromise health, structure, movement and physical ability.

Every dog breed encounters health problems and Weimaraners are no exception. The below is a partial listing of some health issues that may affect Weimaraners. Note that only some, but not all of these are hereditary, genetic, and congenital conditions.

Cervical Spondylomyelopathy (CSM), or Wobbler Syndrome. This is a disease of the cervical spine (at the neck) that is commonly seen in large and giant-breed dogs. CSM is characterized by compression of the spinal cord and/or nerve roots, which leads to neurological signs and/or neck pain. The term wobbler syndrome is used to describe the characteristic wobbly gait (walk) that affected dogs have. Symptoms include a strange, wobbly gait, neck pain and stiffness, weakness, possible short-strided walking, spastic with a floating appearance or very weak in the front limbs, inability to walk, partial or complete paralysis, possible muscle loss near the shoulders, worn or scuffed toenails from uneven walking, increased extension of all four limbs, and difficulty getting up from a lying position. Causes: nutrition in some cases (excess protein, calcium and calories in the case of Great Danes), or fast-growth. Wobbler syndrome is diagnosed via visualization. X-rays, myelographs, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will allow your doctor to view the spine and vertebrae. X-rays should be used mainly to rule out bony disorders while myelographs, CT and MRI are used to visualize the compression of the spinal cord. Diseases that will need to be ruled out though a differential diagnosis include diskospondylitis, neoplasia, and inflammatory spinal cord diseases. The results of the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) analysis should pinpoint the origin of the symptoms.

Elbow dysplasia is a common cause of front-leg lameness in large-breed dogs. Dogs with elbow dysplasia have one or more of the following inherited developmental defects, which may occur singly or in combination: ununited anconeal process, fragmented medial coronoid process, osteochondritis dissecans of the medial condyle of the head of the humerus, and incongruity of growth rate between the radius and ulna resulting in curvature of the radius. The first three defects are related to osteochondrosis. The fourth is related to an enlargement of the epiphyseal growth plate at the head of the radius.

Signs of elbow dysplasia usually appear in puppies at 4 to 10 months of age, but some dogs may not show signs until adulthood, when degenerative joint disease starts. The signs consist of varying degrees of front-leg lameness that worsens with exercise. Characteristically, the elbow is held outward from the chest and may appear swollen.

The diagnosis is made using detailed X-rays of the elbow joint, taken in extreme flexion. Radiologists are particularly interested in the appearance of the anconeal process of the ulna. In a dog with elbow dysplasia, the anconeal process has a rough, irregular appearance due to arthritic changes. Another sign of dysplasia is widening of the joint space associated with a loose, unstable joint. X-rays may be difficult to interpret before a pup is 7 months of age. A CTscan may be required to demonstrate a fragmented coronoid process.

The OFA evaluates X-rays and maintains registries for dogs with elbow dysplasia. Dogs must be 24 months of age or older to be certified by OFA, although it accepts preliminary X-rays on growing pups for interpretation only.

Treatment: Medical treatment is similar to that described for Hip Dysplasia. Surgery is the treatment of choice for most dogs. Several factors, including the age of the dog and the number and severity of the defects, govern the choice of surgical procedure. The more defects in the elbow, the greater the likelihood that the dog will develop degenerative arthritis-with or without surgery.

Hip dysplasia is a genetic disease that primarily affects large and giant breeds of dogs but can also affect medium-sized breeds like Weimaraners. Most Weimaraners who eventually develop hip dysplasia are born with normal hips, but due to their genetic make-up the soft tissues surrounding the joint develop abnormally.

Hypomyelinationsyndrome is a congenital condition characterized by a reduction or absence of myelin in the axons of the central nervous system (CNS) exclusively. A fatty substance that covers the axons (the portions of the nerve cells that transfer impulses to other cells of the body), myelin serves an important function for the nerve cells: as an insulator, protecting the nerve from outside influences, and as an aid for forwarding the process of cellular transmission of nervous system actions. This disease is inherited as a simple autosomal recessive disorder and the carrier frequency has been estimated to be 4.29% within the Weimaraner breed. Hypomyelination is also called “Tremors” and “Shaking puppies” by dog breeders based on the fact that affected puppies have body tremors when awake as early as a few days after birth. Clinical signs resolve in most cases by 3-4 months of age. Some of the dogs may have a mild persistent tremor of the hind legs.

Fig. 1. A Corona radiata, control dog. There is minimal myelin staining. Most cells have small hyperchromatic nuclei compatible with those of oligodendrocytes. Hematoxylin and eosin and luxol fast blue (HE-LFB), x 240. B Corona radiata, affected dog 2. There is no myelin staining. Many of the nuclei are vesicular, suggesting they are astrocytes. HE-LFB, x 240. C Cerebellum, control dog. The folial white matter is relatively normally myelinated. HE-LFB, x 240. D Cerebellum, affected dog 2. The folial white matter is hypomyelinated, relative to the control. HE-LFB, x 240 (Source: Semantic Scholar)

Mandibular Occlusion. Occlusion is a term used to describe the way teeth align with each other. “Normal” occlusion occurs when the upper incisors just overlap the lower incisors (scissor bite), when the lower canines are located at an equal distance between the upper third incisors and the upper canine teeth and when the premolar crown tips of the lower jaw point between the spaces of the upper jaw teeth.

Malocclusion refers to abnormal tooth alignment. There are two types of malocclusion: skeletal and dental. A skeletal malocclusion results when an abnormal jaw length creates a malalignment of the teeth. A dental malocclusion, or malposition, occurs when the upper and lower jaw lengths are considered normal but there may be one or more teeth that are out of normal alignment (malpositioned tooth/teeth).

Class 1 Malocclusion (MAL1). This occurs when individual teeth are in the incorrect position but the jaw lengths are correct. Malocclusion that may fall into this category include: rostral cross-bite, caudal cross-bite, base narrow mandibular canines, ‘lance’ canine teeth, overcrowded and rotated teeth. These may occur in combination with other classes of malocclusion.

Mandibular distoclusion or Class 2 Malocclusion (MAL2). Also known as an overbite, overjet, overshot, and mandibular brachygnathism, it occurs when the lower jaw is shorter relative to the length of the he upper jaw. When the mouth is closed, the teeth of the lower jaw do not occlude (align normally) with their corresponding teeth in the upper jaw. There is a space between the upper and lower incisors when the mouth is closed and the lower incisors may traumatically contact the roof of the mouth behind the upper incisors. The upper premolars are aligned too far toward the nose compared to their counterparts in the lower jaws.

Mandibular mesioclusion or Class 3 Malocclusion (MAL3). Also known as an underbite, undershot, reverse scissor bite, and mandibular prognathism. It occurs when the lower jaw is too long relative to the upper jaw and the lower teeth protrude in front of corresponding upper teeth. If the jaw length discrepancy is minimal, then the upper and lower incisor teeth may meet each other edge to edge resulting in an occlusion referred to as an even or level bite.

Maxillomandibular asymmetry or Class 4 Malocclusion (MAL4). The asymmetry may occur in a number of different ways. It is important to keep in mind that there are 2 upper jaws and 2 lower jaws. All 4 jaws grow/develop independently. Therefore, asymmetry may occur in the lower and/or the upper jaws. When there is a length disparity between the right and left side it is referred to as a rostrocaudal asymmetry (upper and/or lower). When the asymmetry results in a lack of centering of the upper and lower jaws over each other causing a midline shift, then it is referred to as a side-to-side asymmetry. Finally, there may be an asymmetry that is exhibited as an abnormal (increased) space between the upper and lower jaws (may affect one or both sides) and is referred to as an open bite.

Spinal Dysraphism. Spinal dysraphism (SD) in Weimaraner dogs is a genetic disorder present at birth that results from faulty embryonic development. Affected Weimaraners have a defective spinal canal which leads to neurological abnormalities. Puppies born with SD may have difficulties starting to walk due to weakness of their rear legs. Adults with SD show a typical abnormal gait that includes simultaneous movement of the hind legs or “bunny hopping” in the rear. Additional characteristics include weakness and lack of coordination in the rear, together with normal front end coordination and strength. Rarely a “bunny hopping” gait is observed in the front. The condition is not painful and it does not progress during the life of an affected dog. SD is an inherited autosomal recessive disease caused by a mutation in the NKX2-8 gene. Two copies of the mutation are necessary for disease signs to be present with both sexes being affected equally in frequency and severity. Weimaraners that have only one copy of the SD mutation (N/SD) are normal but they are carriers of the disease. When two carriers are bred to each other, 25% of the resulting puppies are expected to be affected and 50% to be carriers. Approximately 1.4% of Weimaraners are estimated to be carriers of SD (N/SD); however, the number of carriers can change with each generation. Weimaraners that are carriers of SD (N/SD) are completely normal, and they can be safely bred to dogs that are non-carriers (N/N) in order to maintain diversity within the breed and to select for other positive attributes in carrier dogs.

The treatment for entropion is surgical correction. A section of skin is removed from the affected eyelid to reverse its inward rolling. In many cases, a primary, major surgical correction will be performed, and will be followed by a second, minor corrective surgery later. Two surgeries are often performed to reduce the risk of over-correcting the entropion, resulting in an outward-rolling eyelid known as ectropion. Most dogs will not undergo surgery until they have reached their adult size at six to twelve months of age.

The prognosis for the surgical correction of entropion is generally good. While several surgeries may be required, most dogs enjoy a pain-free normal life.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a disease of the heart muscle that is characterized by an enlarged heart that does not function properly. With DCM, both the upper and lower chambers of the heart become enlarged, with one side being more severely affected than the other. When the ventricle, or lower chamber, becomes enlarged, its ability to pump blood out into the lungs and body deteriorates. When the heart’s ventricle does not pump enough blood into the lungs, fluid begins to accumulate in the lungs. An enlarged heart soon becomes overloaded, and this often leads to congestive heart failure (CHF). The incidence of DCM in dogs increases with age, usually affecting dogs between four and ten years old. The major symptoms of DCM include lethargy, anorexia, rapid and excessive breathing, shortness of breath, coughing, abdominal distension, and transient loss of consciousness. In some cases, dogs with preclinical (prior to the appearance of symptoms) DCM may be given a questionable diagnosis because it appears to be in fine health. On the other hand, a thorough physical exam can make apparent some of the subtle symptoms of DCM, such as pulse deficits, ventricular or supraventricular premature contractions (within the ventricles and above the ventricles, respectively), and slow capillary refill time. The dog’s breathing sounds may also have a muffled or crackling sound due to the presence of fluid in the lungs. The cause of DCM in dogs is largely unknown. Nutritional deficiencies of taurine or carnitine have been found to contribute to the incidence of DCM in certain breeds such as Dobermans and Cocker Spaniels. Evidence also suggests that some breeds have a genetic susceptibility to the disease. In most breeds, male dogs are more susceptible to the disease than female dogs. In addition to a thorough physical examination of the heart, certain medical tests are needed to confirm a diagnosis of DCM, and exclude other diseases. Radiographic imaging may reveal left ventricular and atrial enlargement, and the presence of fluid in the lungs. An electrocardiogram (EKG) may reveal atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia (rapid beating of the heart). An ultrasound of the heart using echocardiograph imaging is required for a definitive diagnosis of DCM. This test examines the size of the heart, and the ability of the ventricular to contract. In the case of DCM, an echocardiograph will reveal an enlarged left ventricular and left atrial, and low contraction ability.

Autoimmune Disease refers to the immune system’s inability to recognize a dog’s own body and, therefore, begins to attack and reject the body’s own tissues, labeling the tissue as foreign. This can be specific to one type of tissue or generalized. Autoimmune diseases can be life threatening in some cases, depending on what organ or system of the body is affected. Autoimmune disease can take many forms; affecting the skin (Pemphigus), the blood (hemolytic anemia, Immune-mediated thrombocytopenia), the joints (Arthritis), the digestive system (IBD), the adrenal glands (Addison’s), or many systems of the body at once (Lupus). The immune system’s attack on the body tissues can result in the breakdown of tissue, inflammation, pain, and vulnerability to pathogens. The liver and kidneys can be adversely affected by common treatments for autoimmune disease. The liver can become easily overwhelmed and may find it hard to repair damage as fast as it occurs. Support of these organs is important. There are many theories but, as of yet, no one certain cause is found for autoimmune diseases in dogs. It is possible that some may be triggered by such things as vaccines, environmental pollutants, preservatives in food, chemicals, viral infections, stress, allergies, excessive use of corticosteroids and/or antibiotics, and genetics.

Canine Cryptorchidism(undescending of either one or both testicles). This is a common condition among male dogs and has been recognized in dogs for a long time, and even with very selective breeding of dogs with normally descended testicles, the trait will still show itself with relative frequency.

The cryptorchid dog should be neutered because the retained abdominal testicle may be a site for future tumoral growth or testicular torsion. The chance for tumors may be 10 times higher on retained testicles than on normally descended testicles. It is also wise to remember that if left intact, monocryptorchid dogs will possess the ability to breed, and in light of the likelihood of a recessive trait, all offspring will be at best carriers. The neutering of cryptorchid males that otherwise would have been show/breeding potential should be done after 6 months of age to give consideration to the exception for delayed descent in some lines, but an attempt should be made to correlate late descent with an increased incidence of cryptorchidism.

Degenerative Myelopathyis a progressive disease of the spinal cord in older dogs that resembles Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig’s Disease) in people. The disease has an insidious onset typically between 8 and 14 years of age. It begins with a loss of coordination (ataxia) in the hind limbs. The affected dog will wobble when walking, knuckle over or drag the feet. This can first occur in one hind limb and then affect the other. As the disease progresses, the limbs become weak and the dog begins to buckle and has difficulty standing. The weakness gets progressively worse until the dog is unable to walk. The clinical course can range from 6 months to 1 year before dogs become paraplegic. If signs progress for a longer period of time, loss of urinary and fecal continence may occur and eventually weakness will develop in the front limbs.

Gastric Torsion (GDV, bloat/torsion, twisted stomach). Bloat is a disease common to deep-chested dogs such as Weimaraners that can involve twisting or torsion of the stomach with a subsequent blockage of the esophagus at one end and the intestine at the other. The signs of bloat are obvious, with firm swelling on the left side of the abdomen. The dog will also be stressed and in obvious pain. Bloat happens quickly and is a life-threatening condition that requires x-ray confirmation and emergency surgery. It’s often fatal without immediate veterinary attention.

Hyperuricosuria (HUU)(elevated levels of uric acid in the urine). This trait predisposes dogs to form stones in their bladders or sometimes kidneys. These stones often must be removed surgically and can be difficult to treat. Hyperuricosuria is inherited as a simple autosomal recessive trait. The trait can occur in any breed but is most commonly found in the Dalmatian, Bulldog and Black Russian Terrier. This trait has also been found in Weimaraners. A DNA test for this specific mutation can determine if dogs are normal or if they carry one or two copies of the mutation. Dogs that carry two copies of the mutation will be affected and susceptible to develop bladder/kidney stones.

Umbilical Hernias (an opening in the muscle wall where the belly button is located) are quite common, inherited traits in Weimaraners. The hernia allows the abdominal contents to pass through the opening, and is usually diagnosed by finding the soft swelling in the umbilical area. Small, uncomplicated hernias are cosmetic and don’t affect a dog, but surgical correction may be done if preferred. In some cases, umbilical hernias may close spontaneously by the time a puppy reaches 6 months of age.

faces that are associated with the formation of particular varieties and breeds (e.g., Herre and Röhrs 1990; Van Grouw 2018). Well-known examples include Bulldogs, Pugs, and

breeds to be on the small side of the domestic dog body size spectrum (Marchant et al. 2017; Fig. 1G, regression of body size [neurocranium centroid] as the independent

medium-sized and giant breeds, such as the Boxer and Dogue de Bordeaux (Nussbaumer 1982; Marchant et al. 2017). Besides these genetic factors, there is also likely to be

parts of the history of many domestic forms (e.g., dogs [Parker et al. 2017] and chicken [Núñez-León et al. 2019]), this will be notoriously difficult to achieve.

along with a shortening of all limbs, is also known from humans (achondroplasia; Parrot 1878; Horton, Hall and Hecht 2007) and has been compared to “bulldog-type”

associated with morbidity, e.g., in cats and dogs (see earlier; e.g., Waters 2017; Bessant et al. 2018). Human intervention and medical care are often required for

8613371530291

8613371530291