overshot jaw dog pricelist

An overbite might not seem like a serious condition for your dog, but severely misaligned teeth can lead to difficulty eating, gum injuries and bruising, bad breath and different types of dental problems, including tooth decay and gingivitis. Fortunately, there are ways to help fix the problem before it becomes irreversible.

An overbite is a genetic, hereditary condition where a dog"s lower jaw is significantly shorter than its upper jaw. This can also be called an overshot jaw, overjet, parrot mouth, class 2 malocclusion or mandibular brachynathism, but the result is the same – the dog"s teeth aren"t aligning properly. In time, the teeth can become improperly locked together as the dog bites, creating even more severe crookedness as the jaw cannot grow appropriately.

This problem is especially common in breeds with narrow, pointed muzzles, such as collies, shelties, dachshunds, German shepherds, Russian wolfhounds and any crossbred dogs that include these ancestries.

Dental examinations for puppies are the first step toward minimizing the discomfort and effects of an overbite. Puppies can begin to show signs of an overbite as early as 8-12 weeks old, and by the time a puppy is 10 months old, its jaw alignment will be permanently set and any overbite treatment will be much more challenging. This is a relatively narrow window to detect and correct overbites, but it is not impossible.

Small overbites often correct themselves as the puppy matures, and brushing the dog"s teeth regularly to prevent buildup can help keep the overbite from becoming more severe. If the dog is showing signs of an overbite, it is best to avoid any tug-of-war games that can put additional strain and stress on the jaw and could exacerbate the deformation.

If an overbite is more severe, dental intervention may be necessary to correct the misalignment. While this is not necessary for cosmetic reasons – a small overbite may look unsightly, but does not affect the dog and invasive corrective procedures would be more stressful than beneficial – in severe cases, a veterinarian may recommend intervention. There are spacers, braces and other orthodontic accessories that can be applied to a dog"s teeth to help correct an overbite. Because dogs" mouths grow more quickly than humans, these accessories may only be needed for a few weeks or months, though in extreme cases they may be necessary for up to two years.

If the dog is young enough, however, tooth extraction is generally preferred to correct an overbite. Puppies have baby teeth, and if those teeth are misaligned, removing them can loosen the jaw and provide space for it to grow properly and realign itself before the adult teeth come in. Proper extraction will not harm those adult teeth, but the puppy"s mouth will be tender after the procedure and because they will have fewer teeth for several weeks or months until their adult teeth have emerged, some dietary changes and softer foods may be necessary.

An overbite might be disconcerting for both you and your dog, but with proper care and treatment, it can be minimized or completely corrected and your dog"s dental health will be preserved.

Recent research has sought to explain why purchasers remain undeterred by the negative implications of brachycephalic conformation for animal health and welfare while instead prioritizing their characteristic appearance, personality and perceived suitability for certain lifestyles, often based on their low exercise requirements/ability [41,42,43]. With over 90% of current English Bulldog owners stating they would re-purchase this breed again [44], the current popularity of the English Bulldog shows little signs of abating. Consequently, understanding the development of conformation-related disease within the breed, and accurately documenting the disease burden and predispositions within the current breed population [6] are key to assessing and, if possible, redressing some of the main health issues in English Bulldogs. In line with the study hypothesis, the four predispositions with the highest odds in English Bulldogs are all directly associated with the extreme conformation that defines the English Bulldog breed: skin fold dermatitis (× 38.12) [8], prolapsed nictitating membrane gland (× 26.69) [45], mandibular prognathism (× 24.32) [8] and BOAS (19.20) [14]. This evidence supports calls for urgent action to redefine the English Bulldog away from its current extreme conformation and instead to move the breed rapidly towards a moderate conformation on welfare grounds. The results of the current study support the study hypothesis that English Bulldogs show more predispositions than protections among common disorders overall. In line with prior evidence of frequent health issues in the breed [10], these current results support the previous assessments of poor health in (English) Bulldog populations dating back over a hundred years. In 1901, seven years was considered ‘quite an old age’ for a Bulldog; in 1954, critics debated why the breed had ‘a shorter expectation of life’ than others [46, 47]. More recently, Kennel Club surveys of English Bulldog mortality in 2004 and 2014 respectively reported median and mean ages of death of just over six years [48, 49]. Analysis of mortality data from primary-care veterinary clinical records reported a median longevity of 7.2 years for English Bulldogs in the UK [50]. Supporting a shorter lifespan overall in English Bulldogs, the current study reports the median age of English Bulldogs surveyed in 2016 (2.65 years) as significantly younger than of surveyed dogs that are not English Bulldogs (4.42 years). This could be partly explained by a population that skews towards young animals because of a growing popularity of the breed, as seen in steadily increasing Kennel Club registration figures over the last decade [21] and reported in primary-care veterinary practice [50]. However, given that only 9.7% of English Bulldogs in this study were aged over eight years compared with 25.4% of the dogs that are not English Bulldogs, this suggests that relatively few English Bulldogs reach the advanced ages that are typical of other breeds, in line with previous reports, and supports a view of poor overall health in the breed [10, 21].

Likewise, the disease predispositions reported in the current study for English Bulldogs show striking parallels to those previously attributed to the breed. For example, the disorder with the highest predisposition in the current study of English Bulldogs in 2016 was skin fold dermatitis, which was also the most frequently reported disease for Bulldogs in the 1962 BSAVA survey [20]. Similarly, the predisposition of the English Bulldog to prolapsed nictitating membrane gland and to entropion was recognised by veterinary ophthalmologists in 1914 [51]; these conditions were respectively the second and seventh highest disease predispositions in the current study of English Bulldogs in 2016. Mandibular prognathism was the third highest predisposition of English Bulldogs in 2016. This is unsurprising, since this attribute has been a deliberate feature of the Bulldog breed standard since the nineteenth century, with the original wording, that ‘the lower jaw should project considerably in front of the upper, and turn up’, recently modified to require a ‘slightly projecting’ lower jaw instead [8, 52]. The fourth highest predisposition for English Bulldogs in 2016 was BOAS, again reiterating the long-documented propensity of the breed for upper respiratory disorders, reported since the late nineteenth century and previously quantified in 1962 with a high reported incidence of ‘elongated soft palate’ [3, 20]. Thus, the leading predispositions for disease in English Bulldogs, as determined by the current analysis of 2016 data, broadly correspond to disorders that have been long associated with the breed. This provides strong evidence supporting the validity of previous qualitative assessments of breed-related disease in English Bulldogs, but also revives the perennial question of why, since these diseases have been repeatedly documented as impairing Bulldog health for over a century, the breed nevertheless remains so commonly affected by these problems.

In assessing which predispositions and protections to disease particularly differentiate English Bulldogs from the remaining general canine population, it is helpful to focus particularly on ultra-predispositions by breed: i.e. those conditions which are seen at particularly high levels in English Bulldogs, with odds more than four times higher than in dogs that are not English Bulldogs [53]. At the specific disorder level of analysis, the English Bulldog population in the current study showed ultra-predispositions to nine recorded disorders. Of these, four concerned diseases of the skin (skin fold dermatitis, interdigital cyst, demodicosis and pododermatitis). Moreover, additional skin diseases also heavily predominated among the specific-level disorders that were seen between two and four times more frequently in English Bulldogs than other dogs; these comprised pyoderma, moist dermatitis, dermatitis, skin lesions, atopic dermatitis and the non-specific descriptor of ‘allergy’, and also included otitis externa, which is often clinically linked to other allergic skin disease [54]. These various dermatological conditions were necessarily differentiated by the different descriptors used by the originating primary care clinicians. When processing the data, each disorder was recorded once to the greatest possible level of clinical precision. However, these descriptors will inevitably potentially refer to similar or overlapping pathologies, and the certainty of the clinical diagnoses will not necessarily have been equally rigorous or precise in all cases. Therefore, it may be more justified to consider these linked and overlapping conditions at the grouped-level of skin disorders, where 29.3% of Bulldogs were reported with skin disease compared to 12.4% of the general canine population; with an odds ratio of 3.28 after accounting for confounding. These findings confirm that English Bulldogs carry substantially increased risk of skin disease compared with other dogs. While not all skin disease is directly related to exaggerated conformation, skin fold dermatitis, which by definition only occurs in folded skin, was the specific-level disorder to which English Bulldogs were most predisposed and showed a dramatically increased odds ratio of 38.12, presumably reflecting a dangerous synergy of a wider propensity to skin disease combined with the particular issue of wrinkled facial and tail-base skin caused by the brachycephalic and tail conformations that define the English Bulldog breed [8]. Although the English Bulldog’s underlying propensity for skin disease is likely underpinned by complex polygenic and environmental factors, selection away from skin folds represents a comparatively simple biological challenge that should dramatically reduce the prevalence of skin fold dermatitis; however, given the longstanding desire by humans for this feature in English Bulldogs, achieving this welfare-based modification may represent a far greater challenge for human behaviour change than for breeding biology.

Three ophthalmic conditions featured among the nine ultra-predispositions in English Bulldogs at the specific level of disorder: prolapsed nictitating membrane gland, keratoconjunctivitis sicca and entropion. A predisposition of English Bulldogs to entropion (in-turned eyelids) has been reported for over a hundred years [51]. This finding was confirmed by the current study, where 3.9% of the English Bulldogs surveyed were diagnosed with entropion, and the breed showed a markedly increased odds ratio of 11.61 compared to dogs that are not English Bulldogs. Entropion, like skin fold dermatitis, is commonly seen in brachycephalic breeds and is generally attributed to the excess facial skin that results from a foreshortened facial structure; hence, it is usually considered a conformation related disease [55, 56].

Both prolapsed nictitating membrane gland and keratoconjunctivitis sicca were also reported in the current study as ultra-predispositions in English Bulldogs. A diagnosis of prolapsed nictitating membrane gland was 26.79 times more likely in English Bulldogs than in dogs that are not English Bulldogs, while keratoconjunctivitis sicca showed a less extreme but still markedly high odds ratio of 12.24. Yet, despite the greatly elevated odds ratio of prolapsed nictitating membrane gland in English Bulldogs, the 5.7% of English Bulldogs in the wider general population of dogs diagnosed with prolapsed nictitating membrane gland in this study comprise a much lower incidence than the 75% reported in previous Kennel Club surveys of pedigree English Bulldogs, as discussed above [25]. This may indicate genuine and/or methodological differences between the surveyed populations. It may also reflect under-recording of prolapsed nictitating membrane gland in primary care clinical records. The condition (known colloquially as ‘cherry eye’) often manifests in young dogs and is well known within the English Bulldog breed community, where both surgical excision of the gland (often under local anaesthesia) and surgical replacement (recommended by ophthalmologists as a superior technique) are considered possible treatments [57]. Consequently, dogs might be treated for this condition before sale or without the knowledge of primary care practices, potentially resulting in under-recording or under-diagnosis of this disorder in this study. Moreover, although several aetiopathological pathways are proposed for keratoconjunctivitis sicca, one possible cause is following the surgical treatment of a prolapsed nictitating membrane gland, particularly if the tissue is excised rather than replaced (because the nictitating membrane gland contains secretory cells that contribute to lacrimal production) [58, 59]. Therefore, the ultra-predisposition to keratoconjunctivitis sicca noted in the current study may also reflect previous sub-optimal surgical treatment of prolapsed nictitating membrane gland. Thus, the ultra-predisposition of English Bulldogs to these two disorders in this study may be causally linked; further investigation of this association would inform future recommendations for the treatment of prolapsed nictitating membrane gland.

The predisposition of English Bulldogs to BOAS is well documented [14, 60], and is of sufficient clinical concern that The Kennel Club and the University of Cambridge have jointly launched a Respiratory Function Grading Scheme to facilitate selective breeding away from this condition in English Bulldogs and other brachycephalic breeds [61]. It has previously been suggested that up to 45% of English Bulldogs may exhibit clinical signs of BOAS [62]. In the current study, despite a striking odds ratio of 19.2 for BOAS in English Bulldogs compared with dogs that are not English Bulldogs, only 4.2% of the Bulldogs surveyed were formally diagnosed with BOAS during 2016, which is a surprisingly small proportion when compared with previous studies. While it is possible that this reflects biological difference between surveyed populations in different studies, it is much more likely that this discrepancy is chiefly due to normalisation of the condition in primary care practice [63]. For disorders that are so frequent that these become almost a typical expectation for certain breeds, then owners and even veterinarians may no longer even consider these conditions as disorders but instead may normalise these ‘just being part of the breed’ [42, 64, 65]. Normalisation of English Bulldogs with clinical signs of BOAS such as stertor, stridor or stenotic nares as ‘not unhealthy’ appears to be common in the UK, with the owners of over half of brachycephalic dogs with BOAS perceiving these clinical signs (e.g. increased and abnormal respiratory noise) as ‘normal for the breed’ in two separate populations [63, 66].

Mandibular prognathism constitutes a different type of ultra-predisposition in the English Bulldog population surveyed and raises the thorny question of why a conformation that would be considered a serious health issue in one dog breed can be actively selected as a desirable trait in another. As previously mentioned, ‘undershot’ jaw – the physical appearance described by the term mandibular prognathism – has been an explicit requirement of the Bulldog breed standard for over a century [8]. Although mandibular prognathism was the third highest predisposition recorded in the current study, with 24.32 times increased odds in English Bulldogs, this still meant that only 2.1% of the overall English Bulldog population were reported with this condition. Given that mandibular prognathism is a requirement of the breed standard, it is probable that most, if not all, English Bulldogs show this disorder and therefore the current results represent a vast understatement of the real situation of a condition that is ‘normal for the breed’ regardless of not being ‘normal for a dog’ and which therefore will generally go unrecorded in the clinical notes. Similarly, at the grouped level of disorder, ‘tail disorders’ constituted an ultra-predisposition in English Bulldogs with an odds ratio of 6.01 that were recorded in 1.5% of the population. However, since modern English Bulldogs are virtually homozygous for the genetic mutation that causes the ‘screw’ tail, it is probable that many English Bulldogs in this survey similarly went unrecorded for tail abnormalities because these disorders were considered ‘normal for the breed’ [67]. These findings suggest that veterinarians are also becoming normalised to disorders that are accepted as ‘normal for breed’ that would be considered as severe and noteworthy in most other breeds, or alternatively that many veterinarians eventually reach a state of learned helplessness after prolonged contact with events that are outside their personal control [68].

Given these common cognitive biases in owners and veterinarians towards accepting conditions as ‘normal’ in English Bulldogs that would otherwise be considered as disorders in breeds with less extreme conformations, it is therefore all the more striking that English Bulldogs are the breed with the highest proportions of predispositions among common disorders from the breeds that have been reported to date using this VetCompass methodology. English Bulldogs showed predispositions for 55.8% (24/43) of specific-level disorders. In comparison, French Bulldogs showed predispositions for 46.5% (20/43) of disorders [53], Labrador Retrievers showed 34.3% (12/35) predispositions [69] and Staffordshire Bull Terriers showed 11.1% (4/36) predispositions [70]. These results provide strong evidence supporting substantially poorer overall health in English Bulldogs and French Bulldogs compared to Labrador Retrievers and Staffordshire Bull Terriers.

Although dogs had long been divided into loosely-recognised types, the concept of clearly differentiated and strictly delineated breeds was an invention of the Victorian era [2]. Traditional breeds were defined, and new ones created, through detailed descriptions of their physical attributes in ‘breed standards’. Since the visible differences between breeds were key determinants of this new breed system, this evolving culture catalysed and accelerated the exaggeration of distinctive features in some pre-existing types of dogs, both through deliberate efforts to secure their recognition as distinct ‘breeds’ and as a natural consequence of the financial and competitive rewards that often followed the production of dogs with more extreme conformation for the show-ring [3]. In consequence, the modern breeds that we know today can be ranked along a spectrum from mild to extreme conformational exaggeration, ranging from canine-typical (mild conformational exaggeration) to canine-divergent (severe conformational exaggeration) [13, 14]. The combined proportion of predispositions and protections to disease within a breed could be used as a measure of overall health divergence between that breed and the mainstream canine population. Using this measure, English Bulldogs showed health divergence from other dogs for 69.8% (30/43) of specific-level disorders. French Bulldogs showed a similarly high level of health divergence, differing in 77.1% (31/43) from all remaining dogs [53]. In comparison, Labrador Retrievers differed from other dogs for 54.3% (19/35) of disorders [69] while Staffordshire Bull Terriers showed a health divergence metric of just 25.0% (9/36) from other dogs [70]. The two Bulldog breeds with extreme brachycephaly thus both showed notably higher predispositions to disease as well as more disease divergence from other dogs than either Labrador Retrievers or Staffordshire Bull Terriers, although predispositions were relatively higher among English Bulldogs and protections among French Bulldogs. Moreover, as discussed earlier, English Bulldogs showed multiple ultra-predispositions to disease, with odds more than four times higher than dogs that are not English Bulldogs in 9/43 (20.9%) of recorded specific level disorders, while French Bulldogs showed ultra-predispositions to disease in 11/43 (25.6%) of specific-level disorders [53]. In contrast, neither Labrador Retrievers nor Staffordshire Bull Terriers showed any ultra-predispositions to disease at all, with their highest predispositions being an odds ratio of 2.83 for osteoarthritis in Labrador Retrievers and of 2.06 for seizure disorder in Staffordshire Bull Terriers [69, 70]. Overall, therefore, these measures of disease predispositions, divergences and ultra-predispositions seen in English Bulldogs reveal a worrying story of a breed with more disease predispositions than other dogs, which differs widely from other dogs in their patterns of disease and is characterised by several ultra-predispositions to disease. With many of these ultra-predispositions to disease in the English Bulldog being linked to their characteristic extreme physical features, these results broadly confirm an unchanging link between exaggerated conformation and disease first flagged as a concern over a century ago [3].

All breeds, by definition, are different in some ways from the average for the canine population and therefore are likely to show some breed predispositions to, and protections from, disease [6, 8]. For English Bulldogs, the most marked protections for disease, where dogs were less than half as likely to show the specific level disorder as other dogs (an OR of < 0.5), were heart murmur (OR 0.47), flea infestation (OR 0.40), pruritus (OR 0.25), periodontal disease (OR 0.23), lipoma (OR 0.06) and retained deciduous tooth (OR 0.02). At the grouped disorder level, marked protections (OR < 0.5) were reported for appetite disorder (OR 0.43), spinal cord disorder (0.31) and dental disorder (0.25). Some of these protections are somewhat surprising; for example, given the breed’s documented high incidence of hemivertebrae and other vertebral malformations [15, 71,72,73], it is unexpected but reassuring to find that this does not apparently translate into a high level of spinal cord disorder, and may be explained by previous findings that hemivertebrae is more commonly associated with a neurologically normal phenotype in English Bulldogs than for Pugs (Ryan et al., 2017). It is also surprising that a breed with a high prevalence of many other descriptors for skin disease has an apparent protection for pruritus: perhaps this descriptor was subsumed within other more clinically precise descriptors, such as dermatitis or atopic dermatitis, and hence appears artefactually low. It may be that the recorded protection for periodontal disease and dental disorder is linked to the normalisation phenomena described above, but this conclusion is speculative. Other apparent protections for heart murmur and lipoma may indicate true disease protections in the breed, which could be explored in future studies.

Over recent years, The Kennel Club has made concerted efforts to alleviate drivers for extreme conformation from the show-ring. Since 2012, The Kennel Club has identified the English Bulldog as a breed at particularly high risk of conformation-related disease: the breed is currently grouped in Category 3 on The Kennel Club’s Breed Watch list, with show judges urged to prioritise health in their show-ring decisions [74]. Moreover, The Kennel Club breed standard for the English Bulldog has undergone iterative revisions over recent decades, intended to modify its wording to encourage the selection of dogs towards less extreme conformation [8]. Given that only a third of UK dogs are estimated to be registered with The Kennel Club [21]; and that even among this registered subset only a very small proportion are specifically bred for the show-ring [75], the impact of these measures on the general population of English Bulldogs is likely to be minimal. Although show-ring practices have undoubtedly had a profound historical influence in determining the shape of the modern English Bulldog [3], and most dogs described as English Bulldogs today will ultimately be descended from dogs bred for the show-ring in the past, it is easy to overstate the current significance of the show world and Kennel Club breed standard among English Bulldog breeders. While breed standard modifications are to be welcomed, they directly drive change only in the show population, and even then only if judges abide by them [76]. The show Bulldog community argues that its enthusiasts now discourage ultra-extreme conformation and that judges are instructed not to award prizes to dogs with obvious physical compromise. Conversely, the show community claims that ‘overdone’ dogs with extreme conformation tend to be bred outwith the show community by breeders who also select for non-standard ‘novel’ colours, such as merle, which typically command higher prices (Bulldog Breed Council, 2021a). Further research is needed to investigate the social factors and local subcultures that drive and differentiate these breeding priorities, and how best to encourage behavioural change in each group.

The current study had some limitations in addition to those previously reported for the application of primary care veterinary data for canine research [39, 77]. This study relied on the breed identifications recorded on veterinary practice databases. The English Bulldogs in the current study included dogs registered with The Kennel Club as well those that are not. The study dogs are therefore likely to show a range of conformations, ranging from ultra-extreme to relatively moderate, that are consistent with our current acceptance of what constitutes an English Bulldog. Disorder risk for English Bulldogs was compared against all remaining dogs that were not English Bulldogs. Given that 18.74% of dogs in the UK are brachycephalic, this means that a large proportion of the comparator group of dogs in the current study were also brachycephalic. This may have led to a masking effect for disorders linked to the brachycephalic conformation in the current study and suggests that the true levels of predisposition to disorders linked to brachycephaly in the English Bulldog could be much higher than reported here.

Future work could include prospective cohort studies that compare disorder predisposition between English Bulldogs with moderate conformation and English Bulldogs with extreme conformation to evaluate potential welfare gains from conformational change within the breed. Repeating the current study design at defined intervals could also monitor real-world changes in the health of the English Bulldog over time following efforts by UK national groups such as the Brachycephalic Working Group [27].

Enzo is a short-haired Havanese and he was born with his lower jaw shorter than the upper jaw. This is called an Overbite, also referred to as an Overshot Jaw, a Parrot Mouth or Mandibular Brachygnathism. This malocclusion is a genetic change and can be seen in a number of breeds, oftentimes collie related breeds and dachshunds. Occasionally this change happens because of differences in the growth of the upper and lower jaws, and in many cases it doesn’t cause any significant problems other than cosmetically.

Dr. Robin Riedinger evaluated Enzo at his first visit when he was just 11 weeks of age and while the lower jaw was too short, there was no evidence of damage and no indication that this was causing a problem for Enzo. When there is abnormal occlusion of the teeth, it is important to monitor closely for trouble caused by the teeth being aligned improperly. Malocclusions can lead to gum injuries, puncturing of the hard palate, abnormal positioning of adjacent teeth, abnormal wear and bruising of the teeth, permanent damage and subsequent death of one or more teeth, and in the long run, premature loss of teeth. Some malocclusions can be severe enough to interfere with normal eating and drinking.

Within three weeks, when Enzo was only 3.5 months old, it was clear that our doctors would need to intervene. The left and right sides of Enzo’s upper jaw (maxilla) were growing at different rates because the lower canine teeth were being trapped by the upper canine teeth. This is called Dental Interlock. Because the teeth are ‘locked’ in place, the lower jaw cannot grow symmetrically and this creates a number of other problems. Early intervention is critical.

The solution for Dental Interlock is to extract the teeth from the shorter jaw; in this case, the lower ‘baby’ canines and thereby allow the lower jaw (mandible) to grow in the best way possible. This procedure is most effective when the Dental Interlock is discovered early and the extractions are performed quickly. In some cases, this can be as early as ten weeks of age. Dr. Riedinger consulted with a local veterinary dental specialist to confirm the treatment plan and to get advice on extracting the deciduous teeth without damaging the developing adult canines. Dental radiographs are essential to proper extraction technique and also to ensure that there are no other abnormalities below the gumline.

Once extracted, each deciduous canine tooth was about 2 centimeters long; the roots were about 1.5 centimeters. Many people are surprised to learn that the root of a dog’s tooth is so large – 2/3 to 3/4 of the tooth is below the gumline. This is one reason why it is so important to use radiographs to evaluate teeth on a regular basis, not just in a growing puppy. Adult teeth can, and frequently do, have problems that are only visible with a radiograph.

Enzo came through his procedure extremely well. He was given pain medications for comfort and had to eat canned foods and avoid chewing on his toys for the next two weeks to ensure that the gum tissue healed properly. As he continues to grow we will be monitoring how his jaw develops and Dr. Riedinger will also be watching the alignment of his adult canine teeth when they start to emerge around six months of age. Hopefully this early intervention will minimize problems for Enzo in the future.

Enzo is a short-haired Havanese and he was born with his lower jaw shorter than the upper jaw. This is called an Overbite, also referred to as an Overshot Jaw, a Parrot Mouth or Mandibular Brachygnathism. This malocclusion is a genetic change and can be seen in a number of breeds, oftentimes collie related breeds and dachshunds. Occasionally this change happens because of differences in the growth of the upper and lower jaws, and in many cases it doesn’t cause any significant problems other than cosmetically.

Dr. Robin Riedinger evaluated Enzo at his first visit when he was just 11 weeks of age and while the lower jaw was too short, there was no evidence of damage and no indication that this was causing a problem for Enzo. When there is abnormal occlusion of the teeth, it is important to monitor closely for trouble caused by the teeth being aligned improperly. Malocclusions can lead to gum injuries, puncturing of the hard palate, abnormal positioning of adjacent teeth, abnormal wear and bruising of the teeth, permanent damage and subsequent death of one or more teeth, and in the long run, premature loss of teeth. Some malocclusions can be severe enough to interfere with normal eating and drinking.

Within three weeks, when Enzo was only 3.5 months old, it was clear that our doctors would need to intervene. The left and right sides of Enzo’s upper jaw (maxilla) were growing at different rates because the lower canine teeth were being trapped by the upper canine teeth. This is called Dental Interlock. Because the teeth are ‘locked’ in place, the lower jaw cannot grow symmetrically and this creates a number of other problems. Early intervention is critical.

The solution for Dental Interlock is to extract the teeth from the shorter jaw; in this case, the lower ‘baby’ canines and thereby allow the lower jaw (mandible) to grow in the best way possible. This procedure is most effective when the Dental Interlock is discovered early and the extractions are performed quickly. In some cases, this can be as early as ten weeks of age. Dr. Riedinger consulted with a local veterinary dental specialist to confirm the treatment plan and to get advice on extracting the deciduous teeth without damaging the developing adult canines. Dental radiographs are essential to proper extraction technique and also to ensure that there are no other abnormalities below the gumline.

Once extracted, each deciduous canine tooth was about 2 centimeters long; the roots were about 1.5 centimeters. Many people are surprised to learn that the root of a dog’s tooth is so large – 2/3 to 3/4 of the tooth is below the gumline. This is one reason why it is so important to use radiographs to evaluate teeth on a regular basis, not just in a growing puppy. Adult teeth can, and frequently do, have problems that are only visible with a radiograph.

Enzo came through his procedure extremely well. He was given pain medications for comfort and had to eat canned foods and avoid chewing on his toys for the next two weeks to ensure that the gum tissue healed properly. As he continues to grow we will be monitoring how his jaw develops and Dr. Riedinger will also be watching the alignment of his adult canine teeth when they start to emerge around six months of age. Hopefully this early intervention will minimize problems for Enzo in the future.

Undershot is a class III malocclusion that is also referred to as mandibular prognathism, maxillary brachygnathism, mandibular mesioclusion, or an underbite. This malocclusion is characterized by a shorter upper jaw and a longer lower jaw, resulting in lower teeth that are in front of the upper teeth. While this condition is normal for some breeds, such as Bulldogs, in many breeds it is unusual. An undershot jaw occurs when the lower jaw grows faster than normal and becomes longer than the upper jaw, and is usually evident around 8 weeks of age in puppies. This misalignment can cause soft tissue trauma, such as to the lips. When the incisors meet instead of fitting next to each other, it is called a level bite. When the malocclusion causes the lower incisors to be placed in front of the upper incisors, it is called a reverse scissors bite.

The cause of overshot and undershot jaws in dogs relate to the increased or decreased rate of growth of the upper and lower jaws in relation to one another. This can occur due to a: Genetic disorder Trauma; Systemic infection ;Nutritional disorder; Endocrine disorder; Abnormal setting of puppy teeth; Early or late loss of puppy teeth.

After a quick physical exam, your vet may have to sedate your dog in order to perform a thorough oral exam. This will assess your dog’s skull type and teeth location in relation to the teeth on the opposite jaw. Often, the placement of the upper and lower incisors in relation to one another can determine what type of malocclusion your dog has. Your vet will note any areas of trauma due to teeth striking those areas, and any cysts, tumors, abscesses, or remaining puppy teeth that may be present. A dental X-ray can also help to assess the health of the jaws and teeth. These diagnostic methods will lead to a diagnosis of an overshot or undershot jaw in your dog.

Treatment of a jaw misalignment will depend on the severity of the condition. If your dog has a misalignment, but can still bite and chew food without problems, no treatment may be needed. If the misalignment is caught early in a puppy’s life, it may only be temporary and may correct itself over time. However, there are times when intervention may be needed. If your puppy’s teeth are stopping the normal growth of his jaws, then surgery to remove those puppy teeth may be performed. This may allow the jaws to continue to grow, but will not make them grow. For older dogs who are experiencing pain and trauma due to misaligned jaws and teeth, oral surgery is generally performed to extract teeth that are causing trauma, to move teeth so that they fit, or to create space for a misaligned tooth to occupy. Other therapies include crown reductions or braces.

If your dog is genetically programmed to have an overshot or undershot jaw, intervention can help, but will not slow or stop the abnormal growth of either jaw. Prevent jaw misalignments in puppies by not breeding dogs who have overshot or undershot jaws.

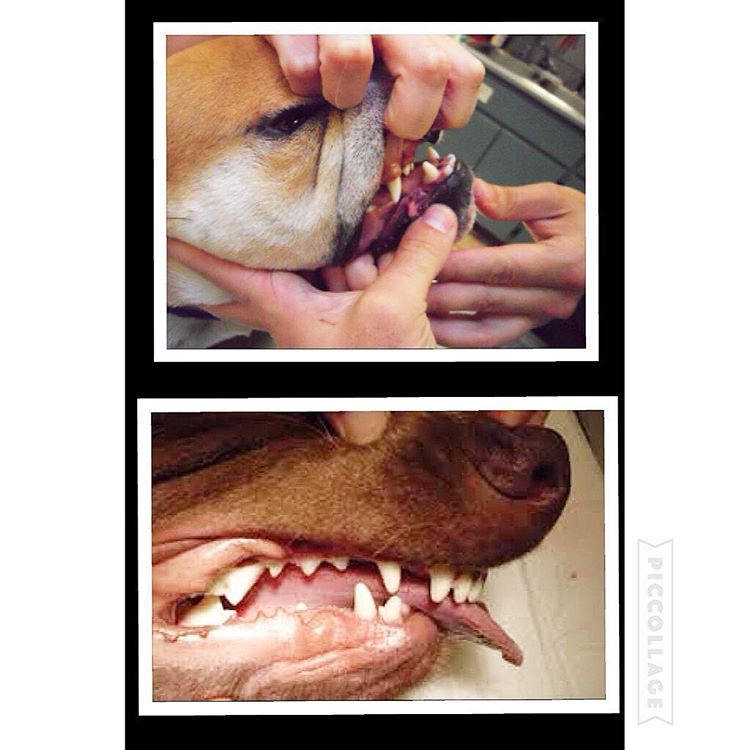

Here is a visual look into what an “undershot” and “overshot” jaw looks like. In recent years, I’ve noticed more and more dogs with this issue. Can a dog live productive life with a malocclusion: (imperfect positioning of the teeth when a jaws closed) Yes but with some issues along the way.

Let’s begin with a puppy will have 28 “puppy teeth” by the time it reaches six months old (this number can vary from breed to breed) By adulthood, most breeds will have a total of 42 teeth. As defined above a malocclusion or simply a misalignment of a dog’s teeth occurs when their bite does not fit accordingly beginning as puppy’s teeth come in and worsening as their adult teeth follow.

the upper jaw is longer than the lower one, an overshot or overbite. When a dogs mouth is closed, a gap between the upper and lower incisors (teeth) will be present. In most cases, puppies are born with a slight over/under bite and with time the problem can correct itself if the gap is not too large. What should be noted is if a dog’s bite remains over/undershot by 8-10 months old, that’s how it will remain for the remainder of its life. In overbite’s the structure may worsen as the permanent teeth come in as they are larger and can damage the soft parts of the mouth. Teeth extractions are sometimes necessary.

Structural dentition of a puppies jaw should be checked very early on to help eliminate this issue. Unfortunately most dog owners won’t notice until is late in the game. More so is the issues of backyard and/or inexplicable breeders breeding dogs with undershot/overshot jaws and potentially passing along this trait to future generations.

With an overbite, the upper jaw is longer than the lower one. When the mouth is closed, a gap between the upper and lower incisors occurs. Puppies born with an overbite will sometimes have the problem correct itself if the gap is not too large. However, a dog’s bite will usually set at ten months old. At this time improvement will not happen on its own. Your pet’s overbite may worsen as the permanent teeth come in because they are larger and can damage the soft parts of the mouth. Teeth extractions are sometimes necessary.

Problems that can arise from malocclusion are; difficulty chewing, picking up food and other objects, dogs with overshot jaws tend to pick up larger chunks of food since they can’t chew nor pick up smaller morsels which can lead to choking and future intestinal issues. These dogs are also prone to tartar and plaque build up which if left untreated can lead to other significant health issues such as heart problems. Other issues are listed below:

What’s important to note is that most malocclusions do not require treatment, it’s simply how a dog will live its full life as. This is important since most breeders breeding for financial gains don’t think about. What can be done is to brush the teeth regularly to prevent abnormal build-up of tartar and plaque. A veterinarian in cases that can be solved will sometimes recommend a dental specialist if a client want to correct the teeth misalignment. Recently I’ve heard o specialist putting “braces” on puppies to realign the teeth.

#dog #dogs #puppy #pup #puppies #puppylove #pets #life #family #bulldog #maltese #mastiff #chihuahua #cockerspaniel #vet #meds #instadog #instagood #instadaily

8613371530291

8613371530291