colonial overshot quotation

The origin of the technique itself may have started in Persia and spread to other parts of the world, according to the author, Hans E. Wulff, of The Traditional Crafts of Persia. However, it is all relatively obscured by history. In The Key to Weavingby Mary E. Black, she mentioned that one weaver, who was unable to find a legitimate definition of the technique thought that the name “overshot” was a derivative of the idea that “the last thread of one pattern block overshoots the first thread of the next pattern block.” I personally think it is because the pattern weft overshoots the ground warp and weft webbing.

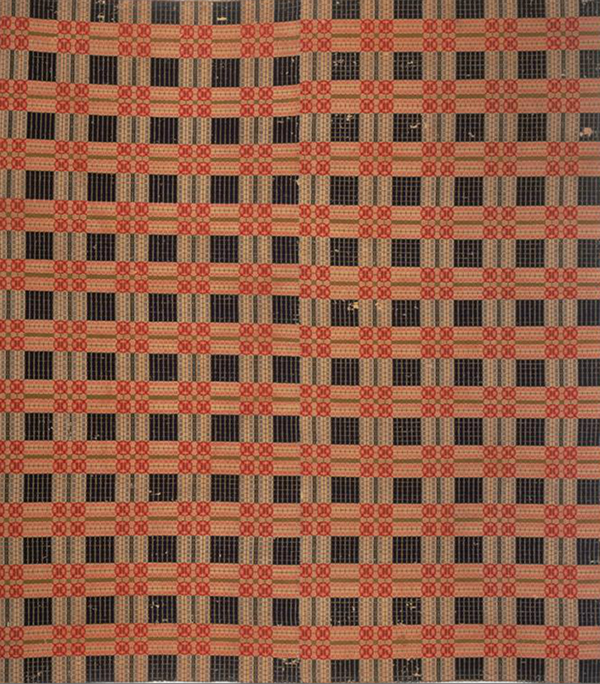

Overshot gained popularity and a place in history during the turn of the 19th century in North America for coverlets. Coverlets are woven bedcovers, often placed as the topmost covering on the bed. A quote that I feel strengthens the craftsmanship and labor that goes into weaving an overshot coverlet is from The National Museum of the American Coverlet:

Though, popular in many states during the early to mid 19th centuries, the extensive development of overshot weaving as a form of design and expression was fostered in rural southern Appalachia. It remained a staple of hand-weavers in the region until the early 20th century. In New England, around 1875, the invention of the Jacquard loom, the success of chemical dyes and the evolution of creating milled yarns, changed the look of coverlets entirely. The designs woven in New England textile mills were predominantly pictorial and curvilinear. So, while the weavers of New England set down their shuttles in favor of complex imagery in their textiles, the weavers of Southern Appalachia continued to weave for at least another hundred years using single strand, hand spun, irregular wool yarn that was dyed with vegetable matter, by choice.

And, due to the nature of design, overshot can be woven on simpler four harness looms. This was a means for many weavers to explore this technique who may not have the financial means to a more complicated loom. With this type of patterning a blanket could be woven in narrower strips and then hand sewn together to cover larger beds. This allowed weavers to create complex patterns that spanned the entirety of the bed.

What makes overshot so incredibly interesting that it was fundamentally a development of American weavers looking to express themselves. Many of the traditional patterns have mysterious names such as “Maltese Cross”, “Liley of the West”, “Blooming Leaf of Mexico” and “Lee’s Surrender”. Although the names are curious, the patterns that were developed from the variations of four simple blocks are incredibly intricate and luxurious.

This is only the tip of the iceberg with regard to the history of this woven structure. If you are interested in learning more about the culture and meaning of overshot, check out these resources!

The National Museum of the American Coverlet- a museum located in Bedford, Pennsylvania that has an extensive collection of traditional and jacquard overshot coverlets. Great information online and they have a “Coverlet College” which is a weekend series of lectures to learn everything about the American coverlet. Check out their website - coverletmuseum.org

Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women – This was an exhibit that traveled from Lowell, Massachusetts, Morehead, Kentucky, Knoxville, Tennessee, Raleigh, North Carolina, and ended at the Royal Museum in Edinburgh, Scotland. The exhibit contained a large number of overshot coverlets and the personal histories of those who wove them. I learned of this exhibit through an article written by Kathryn Liebowitz for the 2001, June/July edition of the magazine “Art New England”. The book that accompanied the exhibit, written by Kathleen Curtis Wilson, contains some of the rich history of these weavers and the cloth they created. I have not personally read the book, but it is now on the top of my wish list, so when I do, you will be the first to know about it! The book is called Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women and I look forward to reading it.

“The Maya collapsed because they overshot the carrying capacity of their environment. They exhausted their resource base, began to die of starvation and thirst, and fled their cities en masse, leaving them as silent warnings of the perils of ecological hubris.”

“When microbes arrived in the Western Hemisphere, he argued, they must have swept from the coastlines first visited by Europeans to inland areas populated by Indians who had never seen a white person. Colonial writers knew that disease tilled the virgin soil of the Americas countless times in the sixteenth century. But what they did not, could not, know is that the epidemics shot out like ghastly arrows from the limited areas they saw to every corner of the hemisphere, wreaking destruction in places that never appeared in the European historical record. The first whites to explore many parts of the Americas therefore would have encountered places that were already depopulated.”

“The Maya collapsed because they overshot the carrying capacity of their environment. They exhausted their resource base, began to die of starvation and thirst, and fled their cities en masse, leaving them as silent warnings of the perils of ecological hubris.”

One of my favorite parts of working on my Ancient Rose Scarf for the March/April 2019 issue of Handwoven was taking the time to research overshot and how it fits into the history of American weaving. As a former historian, I enjoyed diving into old classics by Lou Tate, Eliza Calvert Hall, and Mary Meigs Atwater, as well as one of my new favorite books, _Ozark Coverlets, by Marty Benson and Laura Lyon Redford Here’s what I wrote in the issue about my design:_

“The Earliest weaving appears to have been limited to the capacity of the simple four-harness loom. Several weaves are possible on this loom, but the one that admits of the widest variations is the so-called ‘four harness overshot weave,’—and this is the foremost of the colonial weaves.” So wrote Mary Meigs Atwater in The Shuttle-Craft Book of American Hand-Weaving when speaking of the American coverlet and the draft s most loved by those early weavers.

Overshot, in my mind, is the most North American of yarn structures. Yes, I know that overshot is woven beyond the borders of North America, but American and Canadian weavers of old took this structure and ran with it. The coverlets woven by weavers north and south provided those individuals with a creative outlet. Coverlets needed to be functional and, ideally, look nice. With (usually) just four shaft s at their disposal, weavers gravitated toward overshot with its stars, roses, and other eye-catching patterns. Using drafts brought to North America from Scotland and Scandinavia, these early weavers devised nearly endless variations and drafts, giving them delightful names and ultimately making them their own.

When I first began designing my overshot scarf, I used the yarn color for inspiration and searched for a draft reminiscent of poppies. I found just what I was looking for in the Ancient Rose pattern in A Handweaver’s Pattern Book. When I look at the pattern, I see poppies; when Marguerite Porter Davison and other weavers looked at it, they saw roses. I found out later that the circular patterns—what looked so much to me like flowers—are also known as chariot wheels.

Undershot wheel. Colonial-era mill wrights figured that this type of water wheel transmits water power at 30% efficiency while overshot wheels are 75% efficient and breast wheels are 65%. But this wheel is generating 100% more energy than before, so win-win

[…] but before we could get to the place, where our planters were left, it was so exceeding darke, that we overshot the place a quarter of a mile: there we espied towards the North end of the Iland the light of a great fire thorow the woods, to the which we presently rowed: when wee came right over against it, we let fall our Grapnel neere the shore, & sounded with a trumpet a Call, & afterwardes many familiar English tunes of Songs, and called to them friendly; but we had no answere, we therefore landed at day-breake, and comming to the fire, we found the grasse & sundry rotten trees burning about the place. From hence we went thorow the woods to that part of the Iland directly over against Dasamongwepeuk, & from thence we returned by the water side, round about the Northpoint of the Iland, untill we came to the place where I left our Colony in the yeere 1586. In all this way we saw in the sand the print of the Salvages feet of 2 or 3 sorts troaden that night, and as we entred up the sandy banke upon a tree, in the very browe thereof were curiously carved these faire Romane letters CRO: which letters presently we knew to signifie the place, where I should find the planters seated, according to a secret token agreed upon betweene them & me at my last departure from them, which was, that in any wayes they should not faile to write or carve on the trees or posts of the dores the name of the place where they should be seated; for at my comming away they were prepared to remove from Roanoak 50 miles to the maine. Therefore at my departure from them in Anno 1587 I willed them, that if they should happen to be distressed in any of those places, that then they should carve over the letters or name, a Crosse ✠ in this forme, but we found no such signe of distresse. And having well considered of this, we passed toward the place

As I began to plan the structure of the piece I knew that using an overshot technique for my weaving would probably give me the visual texture that I desired.

The overshot technique in weaving is accomplished by using two different thickness ofthread alternated in the weaving rows. The pattern row is made using the thicker of the two threads and usually skips over several threads to achieve the desired pattern that you are weaving. The thinner of the two threads is woven across the warp before and after each thicker pattern thread to “lock in” the pattern thread. The thinner threads are woven in tabby (weaving speak for plain weave).

I feel that using the overshot weaving technique helped me to capture the textual feeling I wanted for this runner. Here is how the project progressed and a list of the yarns that were used.

With the color pallet and types of yarn I chose and using the overshot technique, I felt like I was able to achieve the look that I wanted for this project. What do you think??

Hamilton believed that the conditions during a revolution were markedly different than those of peacetime. Anarchy was the result when the conditions of revolution overshot the end of a rebellion, and peacetime was still treated, in more minor ways, as a time of reduced warfare. One of his central themes would always be that power must be balanced, or it will harm the country.

It is a popular and well know weave structure with well known motif designs such as Honeysuckle, Snails trails, Cat’s Paw, Young lover’s knot and Maple leaf. Overshot means the weft shoots either over or under the warp.

The Treadling for Overshot is a 2/2 Twill. That is 1-2, 2-3, 3-4, 4-1. Overshot is woven with a thick pattern thread alternating with a thinner tabby thread. The pattern block may be repeated as many times as you like to build up a pleasing block. So it will be pattern thread, tabby a, pattern thread, tabby b. Lift 1 and 3 for tabby a and 2 and 4 for tabby b.

Monks belt, so called because a monks’ status in the monastery was indicated by the pattern woven on the belt is different from the other Overshots motifs as it is woven in 2 blocks on opposites. A block will be either 1 and 2, or 3 and 4. The pattern is created by the varying size of the blocks.

It is not difficult to design your own overshot pattern. A name draft is just one of the ways to do so. The above tablecloth was made by a group of weavers, each wove a square and many of them designed their own name drafts.

2d. This being the day appointed for my departure from hence, I packed up my effects in good time; but the ladies, whose dear companies we were to have to the mines, were a little tedious in their equipment. However, we made a shift to get into the coach by ten o"clock; but little master, who is under no government, would by all means go on horseback. Before we set out I gave Mr. Russel the trouble of distributing a pistole among the servants, of which I fancy the nurse had a pretty good share, being no small favourite. We drove over a fine road to the mines, which lie thirteen measured miles from the Germanna, each mile being marked distinctly upon the trees. The colonel has a great deal of land in his mine tract exceedingly barren, and the growth of trees upon it is hardly big enough for coaling. However, the treasure under ground makes amends, and renders it worthy to be his lady"s jointure. We lighted at the mines, which are a mile nearer to Germanna than the furnace. They raise abundance of ore there, great part of which is very rich. We saw his engineer blow it up after the following manner. He drilled a hole about eighteen inches deep, humouring the situation of the mine. When he had dried it with a rag fastened to a worm, he charged it with a cartridge containing four ounces of powder, including the priming. Then he rammed the hole up with soft stone to the very mouth; after that he pierced through all with an iron called a primer, which is taper and ends in a sharp point. Into the hole the primer makes the priming is put, which is fired by a paper moistened with a solution of saltpetre. And this burns leisurely enough, it seems, to give time for the persons concerned to retreat out of harm"s way. All the land hereabouts seems paved with iron ore; so that there seems to be enough to feed a furnace for many ages. From hence we proceeded to the furnace, which is built of rough stone, having been the first of that kind erected in the country. It had not blown for several moons, the colonel having taken off great part of his people to carry on his air furnace at Massaponux. Here the wheel that carried the bellows was no more than twenty feet diameter; but was an overshot wheel that went with little water. This was necessary here, because water isPage 138

As Amitav Ghosh has recently set out, ‘climate change is but one aspect of a much broader planetary crisis’ (2021: 158). That crisis is understood in terms of processes of resource extraction, settler cultivation, enslavement and indenture, as well modes of terraforming that have dramatically altered, to our collective detriment, the environment upon which life depends. In this way, colonialism, capitalism and catastrophic climate change are structurally – and not simply contingently – linked. Colonialism does not simply prepare the ground for capitalism’s expansionist impulses in the pursuit of markets for its products; colonial extraction remains integral to that expansion. The latter is not a consequence of the economic imperative of capitalism, rather it is a consequence of the logic of colonialism and its political economy. Not recognising the patterns of political economic development that produce the global inequalities associated with climate change undermines the possibility of developing effective and socially just political solutions to the problems we face.

European colonial expansion, from the 15th century onwards, was characterised by systematic resource exploitation, often accompanied by the elimination of Indigenous peoples and their societies (Guha, 1989; Galeano, 1997; Tharoor, 2016; Gilio-Whitaker, 2019). The various East India Companies that were established in the early 17th century participated in what has been called ‘colonialism by corporation’ whereby trading relations gave way to the exercise of sovereignty over other populations and their territories and resources (Phillips and Sharman, 2020). This occurred alongside modes of settler colonialism, which came to involve settler cultivation and the establishment of colonial plantations using coerced labour (Voskoboynik, 2018). These processes brought about significant shifts in the environment that are the basis for ongoing inequalities through to the present.

We suggest that ‘colonialism by corporation’ gives way to various kinds of ‘national colonialism’, culminating in the organisation of global political economy among competing empires. In this way, we do not see empire as a late stage of capitalism, but rather as the framework within which capitalism secures its development. The end of European empires and the rise of new postcolonial nations is not the final realisation of a global, capitalist market economy, but a return to ‘colonialism by corporation’, by transnational corporations with assets beyond the scale of all but a few nation states. This is the context in which we argue for a continuity of colonialism and that capitalism is embedded within colonialism rather than vice versa. It is not simply a matter of ‘adding’ the colonial relation to what is otherwise understood as the capital–labour relation of capitalism, but to understand that the capital–labour relation is mediated nationally and that the national is embedded within broader colonial relations. In this way, we bring land, its dispossession, appropriation and its use centre stage in historical and future accounts of climate change.

Whereas theories of capitalism outline political economy in terms of the relations between nation state and economy, colonialism posits a different political economy of imperial states and post-imperial transnational organisations (Slobodian, 2018; Bhambra, 2021). As such, while it is clear that the effects of climate change are mediated by global inequalities (O’Brien and Leichenko, 2000; Adger et al, 2006), we would go further to argue that climate change has been brought about through the colonial processes implicated in the production and reproduction of those very inequalities: the colonial and racialised dispossessions that severed peoples’ access to land and resources to sustain their livelihoods and set them to work in the plantations and factories that went on to drive extraction through industrial development (Nikiforuk, 2012; Voskoboynik, 2018). Any effective response to climate change, then, must reckon with the histories that have produced it and not just its contemporary manifestations represented in a political economy that effaces its history.

Paradoxically, another way in which colonialism comes to be elided from debates on climate change is via the move to ‘deep history’. Dipesh Chakrabarty, for example, argues that the nature of our present is defined more by ‘the much larger processes of the earth systems and evolutionary history’ (2014: 21) than it is by the colonial and capitalist processes of the last five hundred years. He makes this argument in order to dismiss calls for postcolonial justice in the present on the basis that ‘anthropogenic climate change is not inherently – or logically – a problem of past or accumulated intrahuman injustice’ (2014: 11). He suggests that it is ‘thanks to the poor – that is, to the fact that development is uneven and unfair – that we do not put even larger quantities of greenhouse gases into the biosphere’ (2014: 11). ‘The poor’, in his analysis, are separated from the process of wealth creation that is identified as the problem. That is, he posits ‘the poor’ as a category produced by uneven development processes that themselves have no social relations integral to them. However, the poor are not poor because they are poor; they have been made poor through the very same processes that have made the rest wealthy; that is, colonialism (Rodney, 1972). Another problem with his analytic frame is that it fails to understand the extent to which anthropogenic climate change is historically accumulated.

In contrast to Chakrabarty’s deep history, debates on how to mark shifts in geological time that have occurred around the idea of the ‘Anthropocene’ recognise the colonial actions of humankind as being of the greatest significance. Early arguments about the Anthropocene situated its beginnings with the Industrial Revolution in the latter part of the 18th century. However, more recent research points to an earlier starting point, that of the European colonisation of the lands that we now call the Americas. Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin (2018) have been central to the development of arguments pushing the starting point of the Anthropocene back to this period. Their review of the evidence suggests that human activity has been responsible for changing the state of the Earth; that this new state ‘is marked in geological deposits’ (2018: 301); and that ‘as a geological time-unit’ it began in 1610 (2018: 318). This was primarily a consequence of European arrival in the Americas leading to the deaths of ‘about 10 per cent of all humans on the planet over the period from 1493 to about 1650’ (2018: 158). This led to the collapse of farming across the continent, the regrowth of tropical forests and a significant sequestration of carbon which, they argue, was marked in geological deposits (the Orbis Spike). The 1610 Orbis Spike ‘marks the beginning of today’s globally interconnected economy and ecology, which set Earth on a new evolutionary trajectory’ (2018: 13).

The Anthropocene, then, began with the birth of the colonial modern world; a modern world that was characterised by colonial processes including processes of dispossession, elimination, settlement and extraction. The ‘larger processes of the earth systems’ (Chakrabarty, 2014: 21) have been demonstrated to have been disrupted by human action, namely colonialism. Chakrabarty’s logic of ‘deep history’ is further undermined by focusing on processes that have directly contributed to global inequalities in the present. Jason Hickel (2020b) in a recent piece for the Lancet, for example, argues for a differentiated account of countries’ historical responsibility for carbon emissions based on their territorial (1850–1969) and consumption-based (1970–2015) emissions adjusted for scale and population. Assuming that the atmosphere ‘is a shared and finite resource, and that all people are entitled to an equal share of it’, Hickel then calculates ‘the extent to which nations have exceeded or overshot their fair share of a given safe global emissions budget’ (2020b: e400). His analysis indicates that formerly colonising countries (those he calls the Global North) are responsible for over 90 per cent of excess emissions. This would probably increase further if the ‘national’ share attributed to those countries during the period that they were colonised was also included in the total for the state that colonised them. This clearly indicates the scale of imbalance in the responsibility for climate change and opens up the question of what an equitable response to it would now be.

Consider, for example, one of the most popular mainstream financial instruments: the mortgage. Enslaved people were used as collateral for mortgages centuries before the home mortgage became the defining characteristic of middle America. In colonial times, when land was not worth much and banks didn’t exist, most lending was based on human property. In the early 1700s, slaves were the dominant collateral in South Carolina. Many Americans were first exposed to the concept of a mortgage by trafficking in enslaved people, not real estate, and “the extension of mortgages to slave property helped fuel the development of American (and global) capitalism,” the historian Joshua Rothman told me.

When seeking loans, planters used enslaved people as collateral. Thomas Jefferson mortgaged 150 of his enslaved workers to build Monticello. People could be sold much more easily than land, and in multiple Southern states, more than eight in 10 mortgage-secured loans used enslaved people as full or partial collateral. As the historian Bonnie Martin has written, “slave owners worked their slaves financially, as well as physically from colonial days until emancipation” by mortgaging people to buy more people. Access to credit grew faster than Mississippi kudzu, leading one 1836 observer to remark that in cotton country “money, or what passed for money, was the only cheap thing to be had.”

While “Main Street” might be anywhere and everywhere, as the historian Joshua Freeman points out, “Wall Street” has only ever been one specific place on the map. New York has been a principal center of American commerce dating back to the colonial period — a centrality founded on the labor extracted from thousands of indigenous American and African slaves.

Desperate for hands to build towns, work wharves, tend farms and keep households, colonists across the American Northeast — Puritans in Massachusetts Bay, Dutch settlers in New Netherland and Quakers in Pennsylvania — availed themselves of slave labor. Native Americans captured in colonial wars in New England were forced to work, and African people were imported in greater and greater numbers. New York City soon surpassed other slaving towns of the Northeast in scale as well as impact.

8613371530291

8613371530291