overshot flaking factory

This study utilizes data from the Gault site (41BL323) to address intentionality in Clovis overshot Clovis; overshot; Paleoindian;

Abstract Lohse, Collins, and Bradley ignore or misrepresent the arguments we have made concerning “controlled” overshot flaking and the purported Ice-Age Atlantic Crossing. Here, we summarize our previous work and explain again how it directly tests the explicit claims of Stanford and Bradley (2012; Bradley and Stanford 2004, 2006). We also correct the inaccuracies and false accusations of Lohse, Collins, and Bradley, and refute their belief that arguments should be rejected or accepted on the…Expand

One of the most formal Acheulean large flake blank creation methods is that of Victoria West in southern Africa, dated to ~ 1000 ka at Canteen Kopje (Li et al., 2017). This technique has notable parallels with the Kapthurin Acheulean Levallois including hierarchically organized bifacial surfaces and shaping of convexities on the flatter upper surface through centripetal flaking. However, it differs in some important respects as well. For example, at Canteen Kopje the formal Victoria West cores are rare (< 10% of the core assemblage) (Li et al., 2017), whereas in the Kapthurin Formation Acheulean nearly all the large cores and large shaped tools are Levallois.

Surprisingly, the overall thinness of the Kapthurin specimens does not translate into sharper tip angles, with all assemblages having comparable tip angles except the oldest (and thickest) assemblage: Olorgesailie CL1-1. Creating shallow tip angles was achieved in a variety of ways in the Acheulean, with flaking from multiple directions, or using the dome of a large ventral surface more effective than flaking from one direction only. Rather than sharper tips, the advantage of greater overall thinness for the Living Site specimens may instead lie in the costs of cutting-edge transport, with these pieces being wider for their weight than the other assemblages. Distinctively for an east African Acheulean assemblage (Shipton, 2020), the LHA handaxes and cleavers are not particularly elongate. This may reflect limitations in very large elongate end-struck flake blank creation from Levallois cores, with reduced length compensated for by greater width to maintain cutting edge length. This accords with the previous finding for handaxes and cleavers from both the Living Site and Kariandusi that larger specimens are overall narrower and thinner (perhaps to minimize weight), but have relatively wide tips (and therefore long cutting edges) (Gowlett & Crompton, 1994).

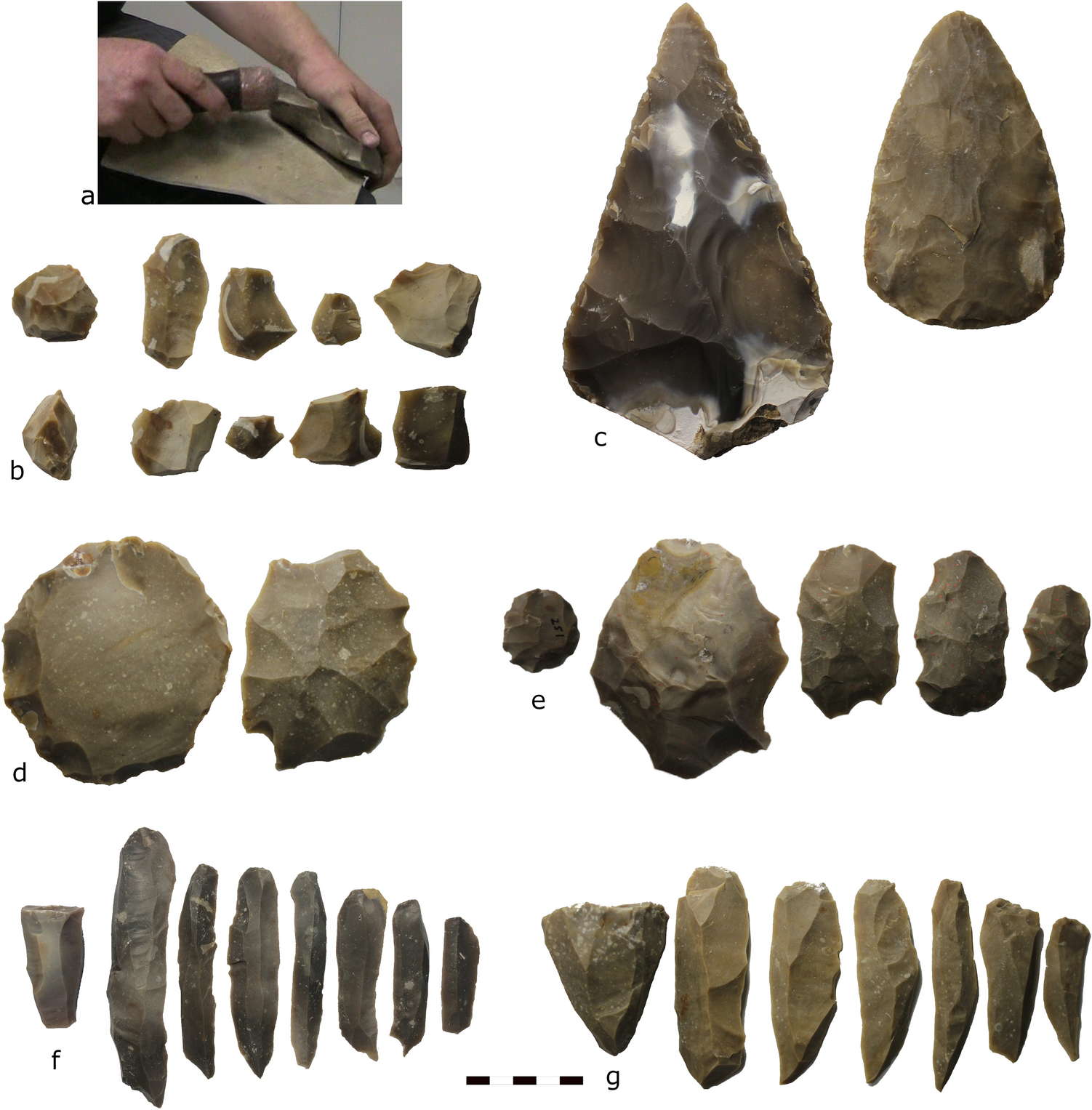

The Acheulean Levallois of the Kapthurin Formation differs from that of the MSA both here and more generally in four respects: it is much larger; it has a lower diversity of preparation techniques; overshot errors are much more frequent; and only one preferential flake seems to have been produced per reduction sequence (i.e. there was no recurrent flaking). The large size of the Levallois cores may be explained by the large cutting tool end products. The need to shape large surfaces from multiple directions probably also partly explains the centripetal flaking patterns, while the extreme force required to strike very large Levallois flakes seems to have often resulted in overshots. Although the flatness of Levallois flakes was later used to facilitate hafting in the MSA, the large size and lack of hafting traces or modifications indicates that these handaxes and cleavers, were, like their predecessors, handheld. This early example of the hierarchically complex Levallois technique (Muller et al., 2017) thus appears to predate hafting in east Africa (e.g. Sahle et al., 2013), which is perhaps unsurprising given the even greater extremes of hierarchical complexity required for hafting (Lombard & Haidle, 2012).

The lack of recurrent flaking on the same surface of the Kapthurin Acheulean Levallois cores may be explained by the need for only a single large flake. However, there was also apparently a lack of repreparation of the dorsal convexities once the first preferential flake had been struck, even if the core was still large enough for further work, and even if the preferential flake was unsuccessful (overshot). Similar, single-use cores were also a feature of large flake blank production in the Victoria West industry (Li et al., 2017) and the Acheulean Levallois at Amane Oukider (Arzarello et al., 2012). Acheulean knappers seem to have moved through unidirectionally organized stages in their flake blank creation, just as façonnage handaxe knapping proceeds from roughing out, to shaping, to thinning, to marginal trimming (Newcomer, 1971). In the MSA by contrast, débordant and other repreparation flakes allow for a return to an earlier stage of the Levallois process and the creation of a renewed preferential surface. Part of the explanation for this, and the greater diversity of preparation techniques noted in the MSA (Tryon et al., 2005), may be the greater diversity of end-products: Rather than two types of shaped tool, MSA Levallois has been characterized as ‘the toolkit within the core’ (Shimelmitz & Kuhn, 2018). Systematic blade production at the Living Site also suggests these hominins may have been shifting away from individual large portable ergonomic tools, to portable toolkits. A parallel may be drawn with the final Acheulean industries in the Levant and India, where the frequency of handaxes and cleavers drops off when small prepared cores become part of the assemblages (Jagher, 2016; Shipton et al., 2013).

8613371530291

8613371530291