overshot flaking price

8)Relationship of ridges to platforms is discussed. Flat surface flaking demonstration shows the value of setting up platforms in alignment with ridges.

9)Examples showing each stage of reduction from raw stone to finished point are discussed along with the goal of each stage. Includes Paleo thinning strategies and a demonstration of how to produce overshot flakes.

Callahan’s approach proved undeniably popular (e.g., [4], 180–181, Table 7.7; [9], 82–87; [10]; [11], 515–6; [14], Fig 2.3; [18], 26–65; [19], Table 5.23; [20], 202–214; [21], 82–110)). To Callahan Stage 1 was the blank, whether flake, core or cobble (cf. Sharrock[[22], 43] who described Stage 1 as the “flake blank” [[22], 43]] but to judge from description and illustrations [[22], Figs. 23–24] was an early-stage worked preform). Stage 2 was the interval in which initial edging of the flake blank creates the preform’s perimeter and, broadly, its plan form. In Stage 3, the preform was thinned across most or all of both faces, flakes extend across the longitudinal midline, moderately convex surfaces are formed on both faces, and edge sinuosity was reduced, all in the process of removing areas of disproportionate thickness. At this stage failure was fairly common, either by transverse fracture, plunging (outrepassé) terminations often called “overshots” in the Clovis literature ([[23], 68], although overshooting may be error more than design ([24], 53], and occur in later prehistoric industries as well [e.g. [17], 118]) or abandonment (e.g., remnant crowns defined by step fractures that failed to terminate normally and therefore failed to remove excess thickness). Stage 4 involved secondary thinning, yielding preforms with relatively flat faces, regular cross-sections and moderately sinuous edges. Stages 5 and higher involved largely haft (including fluted in Paleoindian industries) and perhaps tip modification.

Table 1 summarizes Callahan’s stage-assignment scheme. Note the variability among them, and the complex nature of some of these variables (e.g., nature and size of flake scars, outline regularity) used to describe them. Perhaps as a result, in Callahan’s detailed illustrations of preforms as they progressed through his stages most discrete variables were not coded, measured, or otherwise reported. For instance, Callahan’s ([1], 68, 92, 118) Stage 2–4 exemplars were coded by degree of success, hammer type, and problems encountered—all difficult if possible at all to code in archaeological specimens—not the attributes listed in his scheme. Table 1 also summarizes biface-reduction schemes and preform stages drawn from other sources. Sharrock’s predates the Callahan model but resembles it in many salient respects; others were influenced or guided by Callahan’s approach. Muñiz’s ([17], Table 7.2) somewhat similar model emphasizes outline form, presence/absence of cortex, edging and faceting; it includes only thickness among dimensions. Huckell ([26], 191–194) also devised a similar approach that emphasized extent of flaking across the preform surface, which he considered a diagnostic Clovis characteristic (cf. [17], 122). Villa et al. ([13], 447, Table 3) defined four successive phases in production of South Africa Still Bay bifaces (excluding resharpening of finished specimens) that resembled Callahan’s stages and were defined in part by variables similar to those listed in Table 1.

Although there is broad agreement between schemes and fairly close agreement in some particulars, clearly these heuristic models are not entirely compatible, nor do all include the same set of measures. Some models reported dimensions by stage and employed width/thickness ratios, while others reported no size dimensions at all. Some emphasized cross-section or scar patterns; others ignored these attributes. Where it concerns flaking, some schemes referred to amount, others to pattern, still others to whether primary thinning flakes reached midlines or not. Even where specific measures like width/thickness were used, schemes differed. Andrefsky and Sharrock, for instance, used substantially different edge-angle ranges and width/thickness ratios by stage and Sanders’s Stage-2 edge-angle range was considerably wider than others’. Whatever their differences in width/thickness ratio, most sources reported progressive increase in the ratio as thickness declined disproportionately in the reduction process. Yet elsewhere Bradley ([27], Fig 17.7) reported increasing then declining ratios, such that early-stage preforms were more similar to finished points than were later-stage preforms. Archaeologists agree that there are stages to preform reduction, but apparently not always on the number or defining criteria of those stages. Clearly, there is some difference in which metric or discrete attributes are important and, in the former’s case, which values of them are important.

As above, Callahan’s stages were defined by detailed sets of discrete and continuous technological and flaking variables. Because most such variables were not reported for illustrated specimens in the original source, stage assignments using that source can produce ambiguous results. Only repeated blind tests in which several analysts independently assigned preforms to stages can determine the replicability of Callahan’s scheme. Until then, archaeologists must use their own judgment, applied to a fairly wide range of production preforms that vary not only in degree or stage of reduction but also in toolstone, flake- or core-blank size and form, and size and form of the desired end product. In the face of multiple causality Hill ([11], 515) concluded that “refined flintknapping, such as biface reduction, involved a complex decision-making process, requiring an understanding of many complex, interacting variables.” Stage models may not be the only or always the best method to determine the nature and pattern of complex variation in preform assemblages.

One of the most significant recent studies, of the Clovis biface assemblage at Topper, questioned the validity of stage definitions and replicability of stage assignments, and argued instead that “biface production was technologically a continuous process” ([31], 29). Callahan and other stage systems yielded ambiguous results when applied to Topper bifaces. Instead, Miller and Smallwood found that continuous variables, notably a measure of average number of thinning flakes per edge that they called the Flaking Index ([31], 31)(FI henceforth), better characterized the reduction process than did assignment of bifaces to stages. Complex variation in Topper bifaces could be modeled in continuous measures; any stages defined did not pattern as discrete sets but instead conformed to continuous trends ([31], 33–34). Compared to their FI, Miller and Smallwood concluded that “traditional stage models are ill equipped for describing the variability within the biface assemblage” ([31], 36).

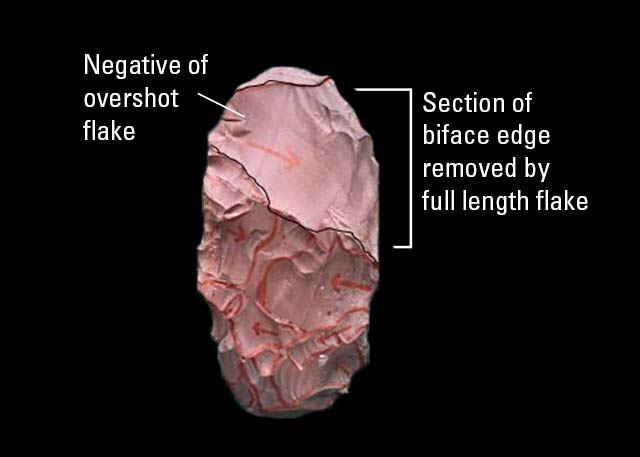

Overshot flaking has become a thing for me recently. An overshot flake is one that travels the complete width of the artefact, and considerably reduces depth in the process. It is a part of the European Solutrean, as well as the North American Clovis technologies. I currently have an abundance of large hard hammer flakes, and my understanding of platform preparation has improved. The result of these coinciding factors is that I have begun to be more consistent with overshot flakes. This is good!

And this is the ventral. I said in a previous post that I am not consistent with overshot flaking, but I was able to turn the proto-handaxe over and after some basic hard hammer platform isolation and preparation remove another one from the opposite face. Because I was working in this considered way I started to collect the removals in order, to understand better the relationship here between my theory and my practice.

The thinning process was working and so I carried on, slowly and systematically. Ultimately things didn’t go as planned and the remnant proto-handaxe is top left in the above photograph. Number 17 was the second overshot flake and 14, 12, 10 and 8 were all good removals. I still haven’t got my handaxe, but I have got a good refitting sequence.

The Transportation Ministry"s director general of aviation, Harry Bakti Gumay, said the aircraft overshot the runway and fell into the sea from a height of about 50m.

Summary: An American Airlines Boeing 737 overshot the runway while landing at the international airport in Kingston, Jamaica early Wednesday, causing 40 injuries but no fatalities, a local newspaper

The Garuda Indonesia Boeing 737-400, whose passengers included 10 Australian journalists and diplomatic staff, overshot the runway of Yogyakarta Airport, at Java, in Indonesia and caught fire.

Then in the 600CC he made up ground on the leading Porter and when Porter overshot at one of the bends near the finish Finnegan grabbed the advantage to win with Porter second and Darran Lindsay third.

8613371530291

8613371530291