overshot hay stacker made in china

According to the dictionary, the jayhawk is a fictitious bird. But the Jayhawk at the Wykoff, Minn., home of Marv Grabau swoops through the air, bearing a 600-pound load of hay.

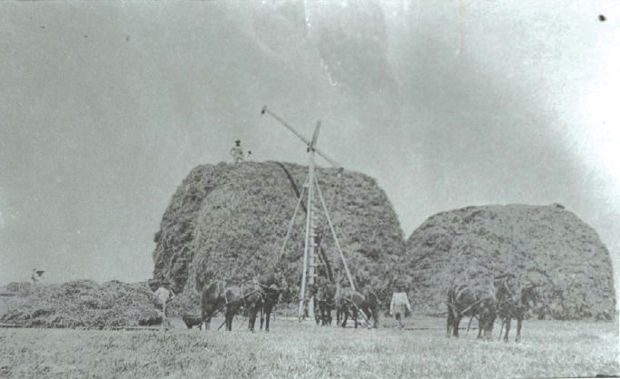

Marv’s Jayhawk is an overshot hay stacker, a piece of horse-drawn farm equipment patented in 1915. Manufactured by the F. Wyatt Mfg. Co. (which evolved into what is today the Hesston Corp.) in Salina, Kan., the long and leggy Jayhawk is a clutch-driven creature that stumps almost every onlooker. Measuring 12 feet wide, 30 feet long and 12 feet high with an 80-inch rear axle, the Jayhawk has a “head” (or “sweep”) originally used to lift hay into bins or cribs. “The head trips like a trip bucket on a tractor,” Marv says. “When it gets up so high, there’s a lever that dumps the load.” The sweep could hold approximately 600 pounds of loose hay as it swept overhead.

The Jayhawk dates to an era when cut hay was left in the fields, and later mounded for storage. “You had your hay windrowed with the old-fashioned dump rake,” Marv explains. “This sweep, or head, would push up, and when the sweep or head was full, you’d go over to a basket or crib – sometimes they had a crib, sometimes they didn’t – and stack it up inside. This particular stacker is 12 feet high, so you could get stacks of hay approximately 12 feet high. Then you’d pack it down and form a top on it like a bread loaf to help it shed water. You just kept moving around in the field, making these stacks until you were done.”

Last August, Marv loaded the stacker onto a trailer and hauled it to Spring Valley, Minn., for the annual Laura Ingalls Wilder Fest tractor show. An unwieldy critter, the Jayhawk fought the process. “It took me three hours just to load it onto the trailer and tie it down, plus the hauling time to town,” Marv says. But it was worth the trouble. “The Jayhawk was the center of attention,” he recalls. “They had about 95 tractors there and 34 implements, and this one drew the most curiosity.

Although the Jayhawk is a deceptively simple conglomeration of steel and cables, chains and wood, Marv invested nearly 40 hours in its restoration. He had to find new rear wheels because the original ones had been removed to allow a tractor to push the stacker. “When they converted it for use with a tractor, it was just a convenience,” he says. “I don’t know if they hooked it to a loader-type tractor or not. A mechanical lift on the front of a tractor is like a fifth wheel on a truck. That’s why they had to get rid of the rear wheels.”

Marv used two tractors with trip buckets to hold the raised sweep up as he worked to loosen the gears. “I had no one to show me how,” he says, “so it was all experimental.” Replacing the 8-foot wood tines on the head involved study and patience, as well as a search for the metal “teeth” that cover the ends of the tines. “The teeth keep the head from digging into the ground and breaking the tines,” he says. “They’re factory metal.” When Marv got the stacker, it had just four tines on it. He needed eight more, and found exactly that number in Waverly, Iowa. The formidable-looking tines now stand supported by a hay bin Marv built to accompany the stacker in the field.

The Jayhawk’s glory days ended in the middle part of the last century when mechanized implements and changing haying methods made the hay stacker obsolete. “After the 1915 horse-drawn model,” Marv says, “it was called a ‘Stackhand’ farm stacker. It was the same as this, only it was self-propelled, more or less. The reason they didn’t (sell well in the north) was that the weather here is so humid that hay rots more easily, so it was better to have it in a hay mow.”

Hay loaders and balers served farmers in a slightly different capacity than the Jayhawk. “The hay loader was the other thing that would’ve come after the hay stacker,” Marv says. “I’ve got a dump rake and the old side-delivery rake here, and the horse mower. I have a chain of command of haying pieces.” Several other restoration projects await, but for now, Marv is simply pleased to be able to display his haying equipment, including the flightless Jayhawk.

It was clear that the people who gathered on AJ Woolstenhulme’s ranch south of Driggs, which he owns with his dad Lance, enjoyed their work a great deal, but it was also a field day in a literal sense. They cut, raked and stacked hay the way ranchers have done in Teton Valley for generations.

Now, Daryl and Ruth still run their ranch almost entirely on horsepower. AJ said that Daryl has been a mentor for him and a driving force behind reviving the skills and techniques needed to harvest hay with horses.

Along with their animals, the members of the Brabant Association brought chuck wagons, hay mowers, bull rakes, timber saws, bailers and the most spectacular piece of equipment on display that day, an overshot stacker.

Janelle Murdock-Ure, Woolstenhulme’s grandmother, grew up on the land that AJ now owns. The land was preserved but some of the more traditional equipment hadn’t been used in some time. With a good amount of hard work AJ and Lance restored the bull rake and overshot stacker when they bought the ranch together.

Murdock-Ure and her family used those exact same pieces of equipment when she was a girl. She drove a dump-rake herself and stacked hay with the overshot. She remembers the family working the ground and seeing handfuls of obsidian shining in the dirt, which the kids would collect.

Come to find out it was Josh Ochsenbein driving those big draft horses and mowing hay on his property. When we called him, he told us that it all started with his grandpa, Daryl Sparks, who was the local sheriff. Josh’s grandpa and Daryl Woolstenhulme of Liberty became good friends through work horses, and his grandpa would go out and help mow and stack the hay for Daryl for years. Josh has also been helping Daryl stack his hay in Liberty.

Because Josh has been helping Daryl with his hay, Daryl has let Josh use his big draft horses and his mowers to mow his fields and stack his hay this year in Montpelier. According to Josh, when you hook the draft horses up to the horse-drawn mower, the wheels start turning which makes the knife move to cut the grass. One horse with a mower can cut an acre and a half in an hour and can run for five hours before needing to rest for the remainder of the day.

He says that mowing this way is slow, but it is cost effective, because it costs so much to farm these days. It takes a whole crew to put up that much hay. He usually works the horses for five to six hours at the most. A lot of them are nursing mothers as well. “So,” according to Daryl, “they can earn their feed.”

He also told us that several other people still mow this way on account of the efficiency. There is a man in Lyman, Wyo., who does it. There are also a few here and there who incorporate it as much as they can, and a few who just play at it. Daryl says they used to do a lot more than they do now because they are slowing down. One of the problems is that they are all dry farms. Their hay is all ready at the same time and they have just a two-week window to “make it happen.” It is all time sensitive. If they had irrigated ground and had two or three crops with a longer time period, they could do it a lot easier.

The Amish still do some of this type of mowing, except they bale their hay. Daryl and Josh are putting their hay up “loose,” like in the thirties and forties. There is a bull rake that goes out and scoops it up, and then it is taken into a stacker that’s called an overshot. It is shot out of the overshot into a loose stack. Someone is on top of the stack and spreads it out.

Daryl has been handling the draft horses since even before he moved into the Bear Lake Valley; 30 to 40 years. He says it’s a passion he has had most of his life. He says in reality he is just a kid off the farm, and the farm is really why he does it. His horses have to earn their keep by putting up their own hay and raising colts.

Daryl is proud to have his grandkids and his daughter on the farm helping him out. They can do just about anything he needs to have help with; they can mow hay, help with the horses, or whatever he needs. They all just love the farm life.

This is the time of the year that Gunnison Ranchers and Farmers harvest most of their crops. The largest by far is the grass hay grown in the Gunnison Area. Farmers moved into Gunnison and tried several types of crops, but found that the growing season was too short. Potatoes were farmed a little longer than most of crops.

The Gunnison hay fields did not always look like they do today. The early ranchers had to pick a lot of rock out of the fields this was done by hand and horse drawn rock sleds. The green meadows you see driving through the Gunnison Valley are all of native grasses, timothy, brome, clover and various types of wheatgrass. The ranchers start flood irrigating their hay fields during the month of May and harvest their hay starting sometime after July 15th and finish before the 1st of October. The process has not changed much over the past 150 years. The way of harvesting the hay crop has change greatly, as I will try to explain on the next page.

In the early 1900’s hay was put up by the use of horse power. The hay was mowed with horse drawn sickle type mowers. The museum have two of these type of mowing machines on display. After the grass was mowed it was put in windrows by using Sulky Rakes. We have two of these rakes on display. After the hay is in a windrow a Buck Rake pulled by horses will bunch the hay up and take large loads of hay to the

stacker. There is a horse drawn Buck Rake at the museum. We have two Overshot Stackers located on the museum grown. There were several different type of hay stackers used up through the early 1960s’. The Overshot, Beaver-slide and Jenkins. All of these stackers were operated by a horse being hooked to a cable that was hooked to the stacker. The horse would pull the stacker teeth loaded with hay and dump it onto the stack, the horse would be lead up about 40 feet dump the hay and then led back to the stacker, this was done for every load of hay.

When automobiles and tractors were invented, machinery took the place of horses. The Allis Chambers, John Deere and Ford were popular tractors used in the Gunnison Valley. The tractor was used for mowing the hay down and pulling several types of machinery in the hay fields. The typical ranch in Gunnison had an Allis Chambers Tractor that could be converted to run backwards and used as a buck rake. A small tractor took the place of the horse that pull the hay on the stacker and dumped it onto the stack. The side delivery rake was developed to put the hay into windrows. Some of the ranchers bought old pickups and converted them run backwards and installing wooden teeth to pick up the hay, (there given name was Doodlebugs) and put it on to the stacker which would dump it onto the stack. The Sulkey Rake started to be used to rake up the hay scatterings that was left by the buck rakes. They became known by the name of scatter rakes. Most of the time there would be two or more men on the stack to move the hay into different areas of the stack. The hay would be stacked into stacks of about 28 to 30 ton of hay per stack. The stacking of loose hay became the thing of the past in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s.

The use of balers and making bales of about 100 pounds, they were tide with wire or twine became very popular. The baller reduced the amount of man power and equipment needed to put the ranchers hay up.

I really enjoyed writing this article. I had the privilege to live the haying stage of the 1950’s. I was able to work for some of the ranchers running most of the equipment. I started out in 1951 and 1952 leading the stacker horse on the Mac and Marge Cooper’s Ranch 5 miles west of town. In 1954 I ran a side delivery rake and scatter rake on Mr. and Mrs. Pete Fields Ranch on Quartz Creek East of Gunnison. In 1955 I started working on the Lee and Polly Spann Ranches. In 1955 and 1956 I mowed hay and ran the side delivery rake, 1957 through 1960 I stacked hay. The Spann ranch is located 3 miles west of Gunnison. It was the greatest experience a boy age 9 to 18 years old could ever have. I know some of these ranchers are not around today, but to them and the ranchers that are still here, I would like say THANK YOU!!!

Makin’ Hay aims to provide quality content that expands your knowledge of the hay and forage industry and helps you become more productive in the field. Makin’ Hay is produced by Vermeer Corporation.

8613371530291

8613371530291