overshot jaw puppy factory

An overbite is a genetic, hereditary condition where a dog"s lower jaw is significantly shorter than its upper jaw. This can also be called an overshot jaw, overjet, parrot mouth, class 2 malocclusion or mandibular brachynathism, but the result is the same – the dog"s teeth aren"t aligning properly. In time, the teeth can become improperly locked together as the dog bites, creating even more severe crookedness as the jaw cannot grow appropriately.

Dental examinations for puppies are the first step toward minimizing the discomfort and effects of an overbite. Puppies can begin to show signs of an overbite as early as 8-12 weeks old, and by the time a puppy is 10 months old, its jaw alignment will be permanently set and any overbite treatment will be much more challenging. This is a relatively narrow window to detect and correct overbites, but it is not impossible.

Small overbites often correct themselves as the puppy matures, and brushing the dog"s teeth regularly to prevent buildup can help keep the overbite from becoming more severe. If the dog is showing signs of an overbite, it is best to avoid any tug-of-war games that can put additional strain and stress on the jaw and could exacerbate the deformation.

If the dog is young enough, however, tooth extraction is generally preferred to correct an overbite. Puppies have baby teeth, and if those teeth are misaligned, removing them can loosen the jaw and provide space for it to grow properly and realign itself before the adult teeth come in. Proper extraction will not harm those adult teeth, but the puppy"s mouth will be tender after the procedure and because they will have fewer teeth for several weeks or months until their adult teeth have emerged, some dietary changes and softer foods may be necessary.

One of the most disappointing things that can happen to a dog breeder is to have what appears to be an almost perfect specimen born and raised, only in the last few months of growth to have it become ‘undershot’. There are puppies born which develop this misfit jaw characteristic in their first few weeks of growth, others which develop it at three or four months and others not until after five months. And it is not necessarily those which are most seriously affected which show it early. One of the worst examples of this protruding lower jaw I have seen was in a cocker Spaniel which up until teething time had a perfect fitting set of teeth; the lower incisors fit right behind the upper, when the mouth was closed. When she was seven months old her lower incisors protruded three-quarters of an inch.

Is this character inherited? Most certainly yes, but in what strange manner, no one has yet been able to say with certainty. And there is the opposite character in which the lower jaw is too short for the upper, known as ‘overshot’. There is as yet no definite measurement for us to say whether the trouble lies in the mandible being too short or the upper jaw has grown too far forward.

Undershot Cocker Spaniels, in a closely bred strain, throws some light on the problem. Among my Cocker Spaniels there is not an undershot puppy or adult in the kennels. But every year a goodly number of undershot puppies appear. Therefore, one might reason that the character is recessive. But let us see. In the first place when they do appear, they do not necessarily appear in a twenty-five percent ratio. A very wonderful bitch named Charm, whose mouth was perfect, was mated to a dog name Red Brucie, whose mouth was also perfect. They produced four puppies every one of which was badly undershot, and one with a perfect mouth. Her name was Kathlyn. Kathlyn was bred to Champ, a son of Roderic. In all the puppies of Roderic, I have not had an undershot puppy, and he was bred to many bitches. But when Champ was mated to Kathryn on many occasions, there were always one or two undershot puppies. But their puppies were so fine that it paid to mate these dogs and destroy the undershot puppies. They had seven litters of which ten puppies were undershot. So here it would seem that the trait was recessive. But let us look further. Some undershot puppies have appeared from other parents. I mated a pair of these, which were not badly deformed and, of five puppies in a litter, not one was undershot. If undershot is a recessive, then all of these puppies should have been undershot.

An interesting study in a strain of long-haired Dachshunds was made by Gruenberg and Lea. Their dogs were so badly overshot that the canine teeth of the under jaw (mandible) occluded behind the upper teeth, instead of in front of them. The tooth size was reduced by the factor and the lower jaw appears to be shortened, and the upper jaw lengthened. This is seen in many breeds. I know a strain of Borzoi which was so badly affected that some of the puppies could not eat out of a pan normally. Gruenberg and Lea found, upon conducting some matings that this trait was inherited as a simple recessive.

The lower jaw or mandible sometimes is much too short. Phillips found this condition to be a recessive, with modifying factors, so that when the maximum expression of these factors occurs the jaw is so short as to cause the death of the dog.

This condition is most often spotted at either the first or second puppy checks or between 6 and 8 months of age as the permanent (adult) teeth erupt. Either the deciduous or permanent lower canines occlude into the soft tissues of the roof or the mouth causing severe discomfort and, possibly, oral nasal fistulae.

Secondly, the growth of the mandible is rostral from the junction of the vertical and horizontal ramus. If the lower canines are embedded in pits in the hard palate, the normal rostral growth of the mandible(s) cannot take place normally due to the dental interlock caused by the lower canines being embedded in hard palate pits. This can cause deviation of the skull laterally or ventral bowing of the mandibles (lower jaws).

Thirdly, the permanent lower canine is located lingual to the deciduous canine. This means that if the deciduous lower canines are in a poor position it is a certainty the permanent teeth will be worse. See the radiograph below. The deciduous canines are on the outside of the jaws and the developing permanent canines are seen in the jaw as small "hats". It is clear that the eruption path of the permanent canines will be directly dorsal and not buccally inclined as is normal.

The permanent successor tooth is located lingual to the deciduous tooth and wholly within the jaw at this stage. Any use of luxators or elevators on the lingual half of the deciduous tooth will cause permanent damage to the developing enamel of the permanent tooth. See the images below showing canines (and also the third incisor) with extensive damage to the enamel. The radiograph also shows how much damage can occur to the teeth - see the top canine and adjacent incisor. Some severely damaged teeth need to be extracted while other can be repaired with a bonded composite. This damage is avoidable with careful technique using an open surgical approach.

Do not try ball therapy with deciduous (puppy) teeth. There are two main reasons for this. Puppy teeth are fragile and can easily break. More importantly, the adult canine tooth bud is developing in the jaw medial to the deciduous canine tooth (see radiograph above in the puppy section). If the deciduous crown tips outwards the root will tip inwards. This will push the permanent tooth bud further medial than it already is.

The intention of the procedure is to keep the pulp alive and allow the shortened lower canines to develop normally and contribute to the strength of the lower jaws.

The advantage of this procedure is that the whole of the root and the majority of the crown remain. The strength and integrity of the lower jaw is not weakened by the procedure and long term results are very good due to the use of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate as a direct pulp dressing.

However, many owners are concerned (rightly) about the loss of the tooth and the weakness it may cause to the lower jaw(s). It is not our preferred option. This is not an easy surgical extraction and the resulting loss of the root causes a weakness in the lower jaws. This is compounded if both lower canines are removed.

Normally a composite resin bite plane is bonded onto the upper teeth (see below) with an incline cut into the sides. The lower canine makes contact with the incline when the mouth closes and, over time, the force tips the tooth buccally. This takes around four to eight weeks. The lower canine will often migrate back into a lingually displaced position when the bite plane is removed. This can occur if the tooth height of the lower canine is too short (stunted). If the lower canine is not self-retained by the upper jaw when the mouth is shut further surgery may be required.

ninja edit: +1 pound puppy, have had a few. Now have Pug. Ultimate kids dog. Did lots of research and bought from very reputable breeder and not factory or backyard where problems end up enhanced.

Hounds: The Otterhound might be known for his shaggy coat and webbed feet, but his bite is certainly the most unique among hound breeds: The jaws are powerful and capable of a crushing grip.

Terriers: Despite his dandelion coif and saucer eyes, the Dandie Dinmont Terrier is equipped with a set of teeth capable of hunting badgers. The standard spares no words in describing both bite and number of teeth: The teeth meet in a tight scissors bite. The teeth are very strong, especially the canines, which are an extraordinary size for a small dog. The canines mesh well with each other to give great holding and punishing power. The incisors in each jaw are evenly spaced and six in number.

Non-Sporting: The Bulldog’s bite is among the breed’s signature features, and the standard is precise in its description: The jaws should be massive, very broad, square and “undershot,” the lower jaw projecting considerably in front of the upper jaw and turning up. … The teeth should be large and strong, with the canine teeth or tusks wide apart, and the six small teeth in front, between the canines, in an even, level row.

Enzo is the Hawthorne Hills Veterinary Hospital Pet of the Month for May. Everyone knows that puppies need vaccines to keep them healthy and protected from diseases. However, it can be easy to underestimate the benefits of thorough and regular examinations when puppies are growing into adulthood. Every breed has special characteristics that make them unique and add to their appeal and sometimes there are physical changes that need to be addressed quickly. For this reason our veterinarians believe in examinations with every vaccine, especially during a puppy’s formative months.

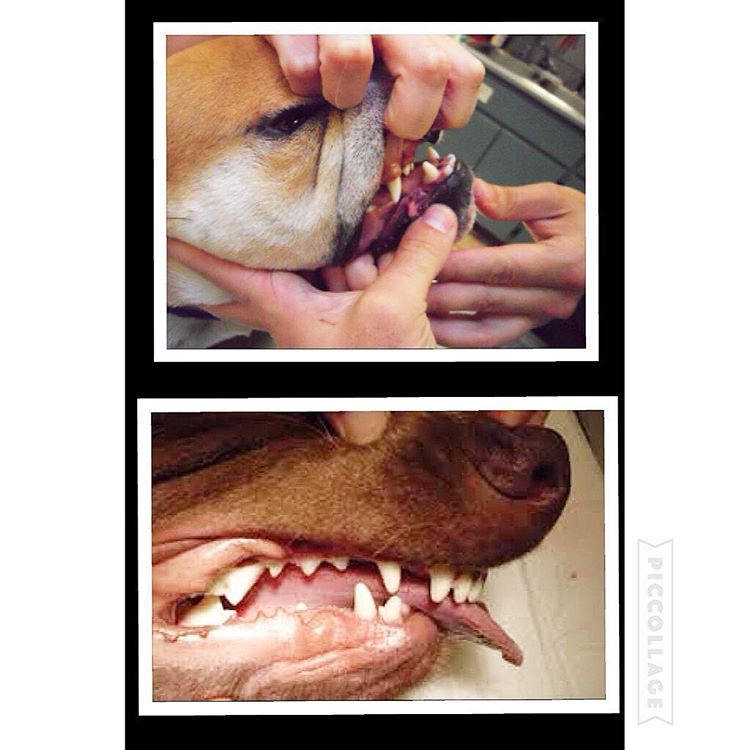

Enzo is a short-haired Havanese and he was born with his lower jaw shorter than the upper jaw. This is called an Overbite, also referred to as an Overshot Jaw, a Parrot Mouth or Mandibular Brachygnathism. This malocclusion is a genetic change and can be seen in a number of breeds, oftentimes collie related breeds and dachshunds. Occasionally this change happens because of differences in the growth of the upper and lower jaws, and in many cases it doesn’t cause any significant problems other than cosmetically.

Dr. Robin Riedinger evaluated Enzo at his first visit when he was just 11 weeks of age and while the lower jaw was too short, there was no evidence of damage and no indication that this was causing a problem for Enzo. When there is abnormal occlusion of the teeth, it is important to monitor closely for trouble caused by the teeth being aligned improperly. Malocclusions can lead to gum injuries, puncturing of the hard palate, abnormal positioning of adjacent teeth, abnormal wear and bruising of the teeth, permanent damage and subsequent death of one or more teeth, and in the long run, premature loss of teeth. Some malocclusions can be severe enough to interfere with normal eating and drinking.

Within three weeks, when Enzo was only 3.5 months old, it was clear that our doctors would need to intervene. The left and right sides of Enzo’s upper jaw (maxilla) were growing at different rates because the lower canine teeth were being trapped by the upper canine teeth. This is called Dental Interlock. Because the teeth are ‘locked’ in place, the lower jaw cannot grow symmetrically and this creates a number of other problems. Early intervention is critical.

The solution for Dental Interlock is to extract the teeth from the shorter jaw; in this case, the lower ‘baby’ canines and thereby allow the lower jaw (mandible) to grow in the best way possible. This procedure is most effective when the Dental Interlock is discovered early and the extractions are performed quickly. In some cases, this can be as early as ten weeks of age. Dr. Riedinger consulted with a local veterinary dental specialist to confirm the treatment plan and to get advice on extracting the deciduous teeth without damaging the developing adult canines. Dental radiographs are essential to proper extraction technique and also to ensure that there are no other abnormalities below the gumline.

Once extracted, each deciduous canine tooth was about 2 centimeters long; the roots were about 1.5 centimeters. Many people are surprised to learn that the root of a dog’s tooth is so large – 2/3 to 3/4 of the tooth is below the gumline. This is one reason why it is so important to use radiographs to evaluate teeth on a regular basis, not just in a growing puppy. Adult teeth can, and frequently do, have problems that are only visible with a radiograph.

Enzo came through his procedure extremely well. He was given pain medications for comfort and had to eat canned foods and avoid chewing on his toys for the next two weeks to ensure that the gum tissue healed properly. As he continues to grow we will be monitoring how his jaw develops and Dr. Riedinger will also be watching the alignment of his adult canine teeth when they start to emerge around six months of age. Hopefully this early intervention will minimize problems for Enzo in the future.

Brachycephalic animals, including dogs and cats, have an exaggerated short and wide skull, and their bottom jaw is disproportionately longer than their upper jaw (commonly known as an ‘undershot’ jaw). These abnormalities are a result of selecting features to comply with pedigree breed standards, where the focus has been on physical traits and appearance rather than on traits that will maintain or improve the health and welfare of the animal.

Brachycephalic dogs have the same number of teeth as all other dog breeds. However, dental and eating complications commonly arise as a result of their teeth growing into a much more narrowed set of gums. This overcrowding of their teeth can lead to an undershot jaw, or abnormally projected bottom jaw, as well as increase their risk of early onset dental disease [2]. Dental disease can often be painful, particularly when dogs are eating soft or hard foods. Although some brachycephalic dog owners feel that these small mouths are adorable, the unfortunate consequences of overcrowded teeth and a misaligned jawline can result in an inability of affected dogs to eat without difficulty. The negative impacts of not being able to eat can further lead to other serious health risks in these dog breeds. See “Dental disease” below for more detail.

An under bite (under shot, reverse scissors bite, prognathism, class 3) occurs when the lower teeth protrude in front of the upper jaw teeth. Some short muzzled breeds (Boxers, English Bull Dogs, Shih-Tzu’s, and Lhasa Apsos) normally have an under bite, but when it occurs in medium muzzled breeds it is abnormal. When the upper and lower incisor teeth meet each other edge to edge, the occlusion is considered an even or level bite. Constant contact between upper and lower incisors can cause uneven wear, periodontal disease, and early tooth loss. Level bite is considered normal in some breeds, although it is actually an expression of under bite.

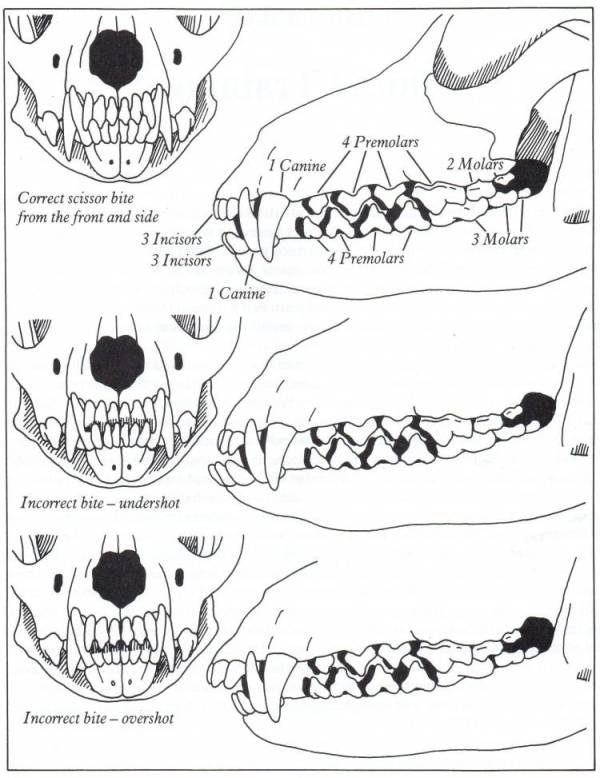

In order to fully understand bite faults, you must also understand what is correct and why. This goes beyond having the right number of the right teeth in the right places. A dog’s dental equipment is a direct inheritance from his wild carnivorous ancestor, the wolf. Dog dentition is also very similar to the wolf’s smaller cousin, the coyote. Figure 1 is a coyote skull, exhibiting a normal canine complement of teeth. Each jaw has six incisors at the front, followed by two canines, then eight premolars (four to a side). When we come to the molars, the top and bottom jaws differ. The lower jaw has six and the upper only four. A normal dog will have a total of 42 teeth.

A wolf grips with the front of his mouth. The four canine teeth puncture the prey. Their overlapping structure (see Fig. 2,combined with jaw strength, prevents the prey animal from pulling free. When catching bad guys, the idea isn’t to poke them full of holes and have them for dinner, but to hang on until the guy with the gun and the handcuffs arrives

Once the prey is down, the premolars are used for biting off chunks of meat that are swallowed hole. The 4th upper premolar and the first lower molar on each side are especially developed for this task. (Fig. 3) The carnasals are the most massive teeth in the canine jaw. They are very sharp and their location mid-way down the length of the jaw puts them at the point where jaw pressure is greatest.

All these specialized teeth are not independent entities. Their position in the jaw is determined by their function and they require a properly formed skull and lower jaw to function efficiently. The muzzle must be long enough and broad enough to accommodate the teeth in their proper locations. The animal must have sufficient bite strength to hold onto whatever it has grabbed, be it prey or perpetrator. Jaw strength comes not only from the muscles, but the shape of the skull.

Figure 4 shows the skulls of a coyote and an Australian Shepherd. Aussies have normally-shaped heads, so the shape of its skull is very similar to that of the coyote. The jaw muscles attach to the lower jaw and along the sagittal crest, the ridge of bone along the top and back of the skull. In between it passes over the zygomatic arch, or cheekbone. Wrapping around the cheekbone gives the bite much more strength than would a straight attachment from topskull to jaw. This attachment also serves to cushion the brain case from the flailing hooves of critters that don’t want to become dinner or get put in a pen.

You will note that the crest on the coyote is more pronounced than on the Aussie and its teeth are proportionally larger. This is a typical difference between domestic dogs and their wild kin. Wild canids need top efficiency from their dental equipment to survive. We have been providing food for our dogs for so long that the need for teeth as large and jaws as strong as their wolf ancestors has long passed. Fig 5 Coyote (left) and Aussie (right). Note the straighter angulation around the zygomatic arch (cheekbone) of the Aussie. Jaw strength is reduced in the dog by a less acute angle around the zygomatic arch. Note the more pronounced angle in the coyote as compared to the Aussie. (Fig. 5) This is another typical difference between wolf or coyote and dog skulls. The larger sagital crest allows for a larger, and therefore stronger, muscle. The only breed with an angulation around the zygomatic arch that approaches that of the wolf is the American Pit Bull Terrier/American Staffordshire Terrier. Pit/AmStaffs also have a relatively short jaw, giving their heads a more cat-like structure: Broad + Short + Strong Muscles = Lots of Bite Strength.

Breeds with long, narrow heads have even straighter angulation around the cheekbone, and therefore an even weaker jaw. The narrow jaw may also cause crowding of the incisors. Toy breeds with round heads often have little or no sagittal crest and very weak jaws. Short-muzzled breeds may not have room for all their teeth resulting in malocclusion, meaning they don’t come together properly. The jaws of short-muzzled breeds may also be of unequal lengths.

The more we have altered skull and jaw shape from the norm, the less efficient the mouth has become. In some cases, this isn’t particularly important. There is no reason for a Collie or a Chihuahua to bite with the strength of a wolf. However, jaws that are so short it is impossible for all the teeth to assume normal positions and undershot bites that prevent proper occlusion of the canines and incisors are neither efficient nor functional, despite volumes of breed lore justifying those abnormalities in breeds where they are considered desirable.

Now that we know what is “right,” for most breeds, anyway, and why it is right, let’s look at what can be wrong, why it is wrong and what, from a breeding standpoint, can be done about it. Most breeds with normal skull structure were originally developed to perform a function (herding, hunting, guarding, etc.) Since that structure is the most efficient it was maintained, with minor variations, in most functional breeds. Typical dental faults in these breeds are missing teeth and malocclusions. It is evident that these faults are inherited, but not a great deal is known about the specifics of that inheritance. In some breeds, some defects appear to have a simple mode of inheritance, but this is not the case across all breeds. That, plus the complex nature of dental, jaw and skull structure, indicates that in most cases the faults are likely to be polygenic, involving a group of genes.

Missing teeth obviously are not there to do the work they are intended for. They should be considered a fault. The degree of the fault can vary, depending on which teeth and how many are missing. The teeth most likely to be absent are premolars, though molars and sometimes incisors may occasionally fail to develop. Missing a first premolar, one of the smallest teeth, is much less a problem than missing an upper 4th premolar, a carnasal. The more teeth that are missing, the more faulty and less functional the bite becomes. If you have a dog with missing teeth, it should not be bred to other dogs with missing teeth or to the near relatives of such dogs. Though multiple missing teeth are not specifically faulted in either Australian Shepherd standard, you should think long and hard before using a dog that is missing more than a couple of premolars. Fig 6 Undershot bite. While the molars and some of the premolars occlude properly, the incisors and canines don"t even meet and are essentially useless. This is a farmed silver fox. Malocclusions this severe are extremely unusual in wild foxes. (photo courtesy Lisa McDonald) Malocclusions most frequently result from undershot and overshot bites, anterior crossbite and wry mouth. An undershot bite occurs when the lower jaw extends beyond the upper. This may happen because the lower jaw has grown too long or the upper jaw is too short. Selecting for shorter muzzles can lead to underbites. An overshot bite is the opposite, with the upper jaw longer than the lower. In either case, the teeth will not mesh properly. With slight over or undershot bites, the incisors may be the only teeth affected, but sometimes the difference in jaw length is extreme (Fig. 6) leaving most or all of the teeth improperly aligned against those in the opposite jaw. A bite that is this far off will result in teeth that cannot be used at all, teeth that interfere with each other, improper wear and, in some cases, damage to the soft tissues of the opposite jaw by the canines.

In wry mouth, one side of the lower jaw has grown longer than the other, skewing the end of the jaw to one side. The incisors and canines will not align properly and may interfere. It is sometimes confused with anterior crossbite, in which some, but not all, of the lower incisors will extend beyond the upper incisors but all other teeth mesh properly.

Minor malocclusions, including “dropped” incisors and crooked teeth, also occur in some dogs. Dropped incisors are center lower incisors that are shorter than normal. Sometimes they will tip slightly outward and, when viewed in profile, may give the appearance of a bite that is slightly undershot. Dropped incisors tend to run in families and are therefore hereditary. Crooked teeth may be due to crowding in a too-small or too-narrow jaw or the result of damage to the mouth, though the former is more likely.. Fig 7 Even (level) bite. This is a wolf. Some consider an even, or level, bite to be a type of malocclusion. Breed standards vary on whether they do or do not fault it. In the Australian Shepherd, the ASCA standard faults it while the AKC standard does not. There is clearly no consensus among dog people. Those who fault the even bite claim that it causes increased wear of the incisors, but there is little evidence to support this. A number of years ago the author, upon coming across a wolf with an even bite (Fig. 7), undertook a survey of wolf dentition. Teeth and jaws were inspected on 39 wolves, 9 of which were captive and the balance skulls of wild wolves trapped over a wide span of time and geography. Of the 39, 16 had even bites. This included five of the captive group, all of whom were related. Even discounting those, fully a third of the wild wolves had even bites. No structural fault is tolerated to this degree in a natural species, particularly in a feature so critical to the survival of that species.

Result = NO pups with underbites but some may be carries of "w" and/or "y" Using the same example above lets" say the sire is also carrying "w" like the dam. Results = you COULD have a puppy with a slight underbite IF mom passed her "w" AND the dad passed his "w" also. The pups with the slight underbite would be "ww"

In order to fully understand bite faults, you must also understand what is correct and why. This goes beyond having the right number of the right teeth in the right places. A dog’s dental equipment is a direct inheritance from his wild carnivorous ancestor, the wolf. Dog dentition is also very similar to the wolf’s smaller cousin, the coyote. Figure 1 is a coyote skull, exhibiting a normal canine complement of teeth. Each jaw has six incisors at the front, followed by two canines, then eight premolars (four to a side). When we come to the molars, the top and bottom jaws differ. The lower jaw has six and the upper only four. A normal dog will have a total of 42 teeth.

The canines are most critical to catching and holding prey. Readers familiar with police K9s or Schutzhund will know that the preferred grip is a “full mouth bite:” The dog grasps the suspect’s arm or leg well into its mouth, between its molars and premolars and behind the canines. This is not the way a wolf does it.A wolf grips with the front of his mouth. The four canine teeth puncture the prey. Their overlapping structure (see Fig. 2)combined with jaw strength prevents the prey animal from pulling free. When catching bad guys, the idea isn’t to poke them full of holes and have them for dinner, but to hang on until the guy with the gun and the handcuffs arrives.

Once the prey is down, the premolars are used for biting off chunks of meat that are swallowed hole. The 4th upper premolar and the first lower molar on each side, the carnasals, are especially developed for this task. (Fig. 3) These are the most massive teeth in the canine jaw. They are very sharp and their location mid-way down the length of the jaw puts them at the point where jaw pressure is greatest.

All these specialized teeth are not independent entities. Their position in the jaw is determined by their function and they require a properly formed skull and lower jaw to function efficiently. The muzzle must be long enough and broad enough to accommodate the teeth in their proper locations. The animal must have sufficient bite strength to hold onto whatever it has grabbed, be it prey or perpetrator. Jaw strength comes not only from the muscles, but the shape of the skull.

Figure 4shows the skulls of a coyote and an Australian Shepherd. Aussies have normally-shaped heads, so the shape of its skull is very similar to that of the coyote. The jaw muscles attach to the lower jaw and along the sagittal crest, the ridge of bone along the top and back of the skull. In between it passes over the zygomatic arch, or cheekbone. Wrapping around the cheekbone gives the bite much more strength than would a straight attachment from topskull to jaw. This attachment also serves to cushion the brain case from the flailing hooves of critters that don’t want to become dinner or get put in a pen.

You will note that the crest on the coyote is more pronounced than on the Aussie and its teeth are proportionally larger. This is a typical difference between domestic dogs and their wild kin. Wild canids need top efficiency from their dental equipment to survive. We have been providing food for our dogs for so long that the need for teeth as large and jaws as strong as their wolf ancestors has long passed.

Jaw strength is reduced in the dog by a less acute angle around the zygomatic arch. Note the more pronounced angle in the coyote (Fig. 5a) as compared to the Aussie (Fig. 5b).This is another typical difference between wolf or coyote and dog skulls. The larger sagital crest allows for a larger, and therefore stronger, muscle. The only breed with an angulation around the zygomatic arch that approaches that of the wolf is the American Pit Bull Terrier/American Staffordshire Terrier. Pit/AmStaffs also have a relatively short jaw, giving their heads a more cat-like structure: Broad + Short + Strong Muscles = Lots of Bite Strength.

Breeds with long, narrow heads have even straighter angulation around the cheekbone, and therefore an even weaker jaw. The narrow jaw may also cause crowding of the incisors. Toy breeds with round heads often have little or no sagittal crest and very weak jaws. Short-muzzled breeds may not have room for all their teeth resulting in malocclusion, meaning they don’t come together properly. The jaws of short-muzzled breeds may also be of unequal lengths.

The more we have altered skull and jaw shape from the norm, the less efficient the mouth has become. In some cases, this isn’t particularly important. There is no reason for a Collie or a Chihuahua to bite with the strength of a wolf. However, jaws that are so short it is impossible for all the teeth to assume normal positions and undershot bites that prevent proper occlusion of the canines and incisors are neither efficient nor functional, despite volumes of breed lore justifying those abnormalities in breeds where they are considered desirable.

Now that we know what is “right,” for most breeds, anyway, and why it is right, let’s look at what can be wrong, why it is wrong and what, from a breeding standpoint, can be done about it. Most breeds with normal skull structure were originally developed to perform a function (herding, hunting, guarding, etc.) Since that structure is the most efficient it was maintained, with minor variations, in most functional breeds. Typical dental faults in these breeds are missing teeth and malocclusions. It is evident that these faults are inherited, but not a great deal is known about the specifics of that inheritance. In some breeds, some defects appear to have a simple mode of inheritance, but this is not the case across all breeds. That, plus the complex nature of dental, jaw and skull structure, indicates that in most cases the faults are likely to be polygenic, involving a group of genes.

Malocclusions most frequently result from undershot and overshot bites, anterior crossbite and wry mouth. An undershot bite occurs when the lower jaw extends beyond the upper. This may happen because the lower jaw has grown too long or the upper jaw is too short. Selecting for shorter muzzles can lead to underbites. An overshot bite is the opposite, with the upper jaw longer than the lower. In either case, the teeth will not mesh properly. With slight over or undershot bites, the incisors may be the only teeth affected, but sometimes the difference in jaw length is extreme (Fig. 6)

leaving most or all of the teeth improperly aligned against those in the opposite jaw. A bite that is this far off will result in teeth that cannot be used at all, teeth that interfere with each other, improper wear and, in some cases, damage to the soft tissues of the opposite jaw by the canines.

In wry mouth, one side of the lower jaw has grown longer than the other, skewing the end of the jaw to one side. The incisors and canines will not align properly and may interfere. It is sometimes confused with anterior crossbite, in which some, but not all, of the lower incisors will extend beyond the upper incisors but all other teeth mesh properly.

Minor malocclusions, including “dropped” incisors and crooked teeth, also occur in some dogs. Dropped incisors are center lower incisors that are shorter than normal. Sometimes they will tip slightly outward and, when viewed in profile, may give the appearance of a bite that is slightly undershot. Dropped incisors tend to run in families and are therefore hereditary. Crooked teeth may be due to crowding in a too-small or too-narrow jaw or the result of damage to the mouth, though the former is more likely.

Some consider an even, or level, bite to be a type of malocclusion. Breed standards vary on whether they do or do not fault it. In the Australian Shepherd, the ASCA standard faults it while the AKC standard does not. There is clearly no consensus among dog people. Those who fault the even bite claim that it causes increased wear of the incisors, but there is little evidence to support this. A number of years ago the author, upon coming across a wolf with an even bite (Fig. 7), undertook a survey of wolf dentition. Teeth and jaws were inspected on 39 wolves, 9 of which were captive and the balance skulls of wild wolves trapped over a wide span of time and geography. Of the 39, 16 had even bites. This included five of the captive group, all of whom were related. Even discounting those, fully a third of the wild wolves had even bites. No structural fault is tolerated to this degree in a natural species, particularly in a feature so critical to the survival of that species.

Teeth — scissors bite, in which the outer side of the lower incisors touches the inner side of the upper incisors. Undershot or overshot bite is a disqualification. Misalignment of teeth (irregular placement of incisors) or a level bite (incisors, meet each other edge to edge) is undesirable, but not to be confused with undershot or overshot. Full dentition, obvious gaps are serious faults.

Color — rich, lustrous golden of various shades. Feathering may be lighter than rest of coat. With the exception of graying or whitening of face or body due to age, any white marking, other than a few white hairs on the chest, should be penalized according to its extent. Allowable light shadings are not to be confused with white markings. Predominant body color which is either extremely pale or extremely dark is undesirable. Some latitude should be given to the light puppy whose coloring shows promise of deepening with maturity. Any noticeable area of black or other off-color hair is a serious fault.

Occlusion is defined as the relationship between the teeth of the maxilla (upper jaw) and mandibles (lower jaw). When this relationship is abnormal a malocclusion results and is also called an abnormal bite or an overbite in dogs and cats.

8613371530291

8613371530291