overshot patterns for weaving quotation

This post may help explain how my needle pillow cloth was woven. These pieces were made on the same warp. I had made a dozen or so pillow fronts and backs (in plain weave or tabby). Then I got creative and played with ideas of what else could be woven on the same warp. This is a scroll I made. I used the fabric I wove on the needle pillow warp for the background. It measures 7 ¾” x 26” including fringe.

I wove some samples and decided to make this for my scroll. The warp was handspun singles from Bouton. I wanted to see if I could use this fragile cotton for a warp. I used a sizing for the first time in my weaving life. The pattern weft is silk and shows up nicely against the matt cotton.

Here is a piece with two samples. The I used silk chenille that I’ve been hording dyed with black walnuts. In one part I used the chenille as the pattern weft. It looks similar to the needle pillows except I used only 1 block. The tabby was black sewing thread, I believe. For the flat sample, I used the reverse: the chenille for the tabby weft and the sewing thread for the pattern weft. Again I only used one of the blocks.

For this sample I used all sewing thread (easier with only one shuttle.) Again I used only one block and the pattern and tabby wefts were sewing thread. I do love to try things.

This illustration and quote are in The Weaving Book by Helen Bress and is the only place I’ve seen this addressed. “Inadvertently, the tabby does another thing. It makes some pattern threads pair together and separates others. On the draw-down [draft], all pattern threads look equidistant from each other. Actually, within any block, the floats will often look more like this: [see illustration]. With some yarns and setts, this pairing is hardly noticeable. If you don’t like the way the floats are pairing, try changing the order of the tabby shots. …and be consistent when treadling mirror-imaged blocks.”

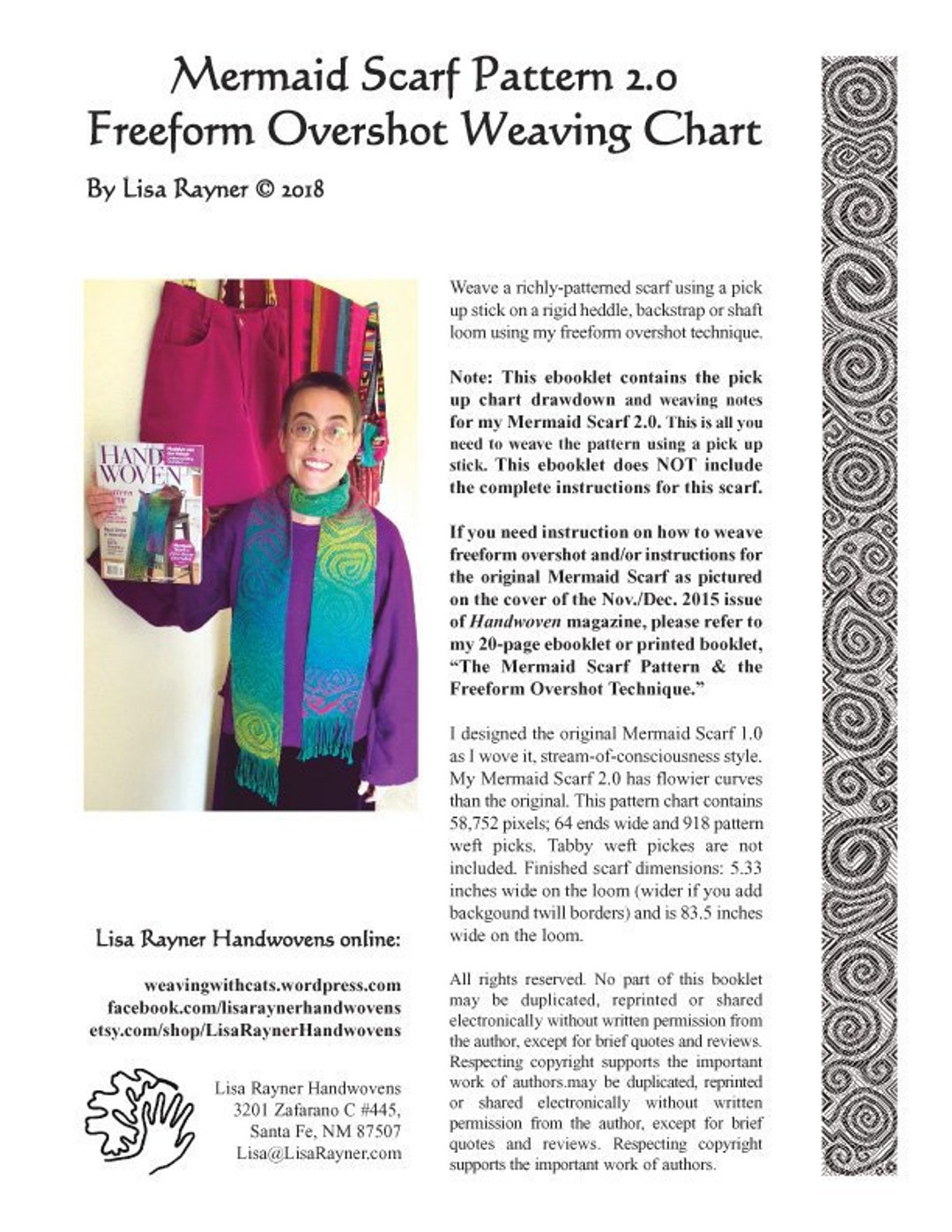

Woven by Rachel SnackWeave two overshot patterns with the same threading using this downloadable weave draft to guide you. This pattern features the original draft along with one pattern variation. Some yarns shown in the draft are available to purchase in our shop: 8/2 cotton, wool singles, 8/4 cotton (comparable to the 8/4 linen shown).

please note: this .pdf does not explain how to read a weaving draft, how to interpret the draft onto the loom, or the nuances of the overshot structure.

The origin of the technique itself may have started in Persia and spread to other parts of the world, according to the author, Hans E. Wulff, of The Traditional Crafts of Persia. However, it is all relatively obscured by history. In The Key to Weavingby Mary E. Black, she mentioned that one weaver, who was unable to find a legitimate definition of the technique thought that the name “overshot” was a derivative of the idea that “the last thread of one pattern block overshoots the first thread of the next pattern block.” I personally think it is because the pattern weft overshoots the ground warp and weft webbing.

Overshot gained popularity and a place in history during the turn of the 19th century in North America for coverlets. Coverlets are woven bedcovers, often placed as the topmost covering on the bed. A quote that I feel strengthens the craftsmanship and labor that goes into weaving an overshot coverlet is from The National Museum of the American Coverlet:

Though, popular in many states during the early to mid 19th centuries, the extensive development of overshot weaving as a form of design and expression was fostered in rural southern Appalachia. It remained a staple of hand-weavers in the region until the early 20th century. In New England, around 1875, the invention of the Jacquard loom, the success of chemical dyes and the evolution of creating milled yarns, changed the look of coverlets entirely. The designs woven in New England textile mills were predominantly pictorial and curvilinear. So, while the weavers of New England set down their shuttles in favor of complex imagery in their textiles, the weavers of Southern Appalachia continued to weave for at least another hundred years using single strand, hand spun, irregular wool yarn that was dyed with vegetable matter, by choice.

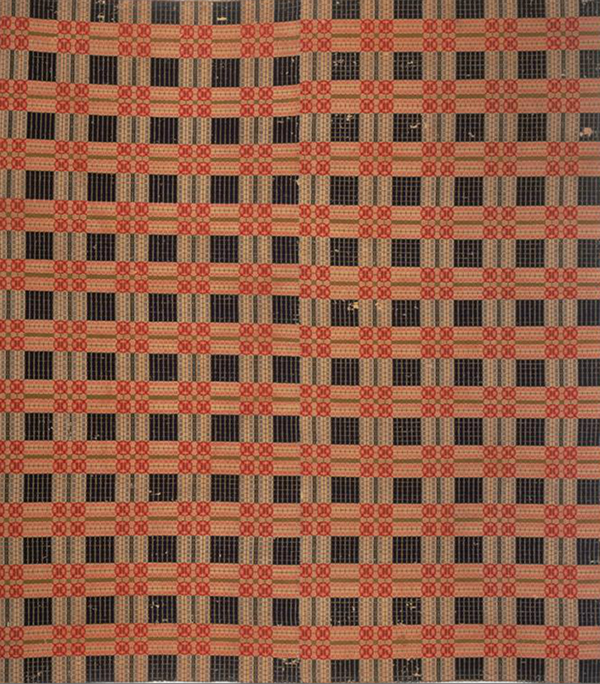

Designs were focused on repeating geometric patterns that were created by using a supplementary weft that was typically a dyed woolen yarn over a cotton plain weave background. The designs expressed were often handed down through family members and shared within communities like a good recipe. And each weaver was able to develop their own voice by adjusting the color ways and the treadling arrangements. Predominately, the homestead weavers that gave life and variations to these feats of excellent craftsmanship were women. However, not every home could afford a loom, so the yarn that was spun would have been sent out to be woven by the professional weavers, who were mostly men.

And, due to the nature of design, overshot can be woven on simpler four harness looms. This was a means for many weavers to explore this technique who may not have the financial means to a more complicated loom. With this type of patterning a blanket could be woven in narrower strips and then hand sewn together to cover larger beds. This allowed weavers to create complex patterns that spanned the entirety of the bed.

What makes overshot so incredibly interesting that it was fundamentally a development of American weavers looking to express themselves. Many of the traditional patterns have mysterious names such as “Maltese Cross”, “Liley of the West”, “Blooming Leaf of Mexico” and “Lee’s Surrender”. Although the names are curious, the patterns that were developed from the variations of four simple blocks are incredibly intricate and luxurious.

This is only the tip of the iceberg with regard to the history of this woven structure. If you are interested in learning more about the culture and meaning of overshot, check out these resources!

The National Museum of the American Coverlet- a museum located in Bedford, Pennsylvania that has an extensive collection of traditional and jacquard overshot coverlets. Great information online and they have a “Coverlet College” which is a weekend series of lectures to learn everything about the American coverlet. Check out their website - coverletmuseum.org

Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women – This was an exhibit that traveled from Lowell, Massachusetts, Morehead, Kentucky, Knoxville, Tennessee, Raleigh, North Carolina, and ended at the Royal Museum in Edinburgh, Scotland. The exhibit contained a large number of overshot coverlets and the personal histories of those who wove them. I learned of this exhibit through an article written by Kathryn Liebowitz for the 2001, June/July edition of the magazine “Art New England”. The book that accompanied the exhibit, written by Kathleen Curtis Wilson, contains some of the rich history of these weavers and the cloth they created. I have not personally read the book, but it is now on the top of my wish list, so when I do, you will be the first to know about it! The book is called Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women and I look forward to reading it.

Centerpiece sized handwoven tabletop runner crafted by Kate Kilgus, Harrisville, New Hampshire. Overshot weaving in royal blue and white cottons. This handcrafted textile can be used on the dining table, buffet, bureau, or coffee table. A two shuttle weave, overshot allows for the creation of curves

One of my favorite parts of working on my Ancient Rose Scarf for the March/April 2019 issue of Handwoven was taking the time to research overshot and how it fits into the history of American weaving. As a former historian, I enjoyed diving into old classics by Lou Tate, Eliza Calvert Hall, and Mary Meigs Atwater, as well as one of my new favorite books, _Ozark Coverlets, by Marty Benson and Laura Lyon Redford Here’s what I wrote in the issue about my design:_

“The Earliest weaving appears to have been limited to the capacity of the simple four-harness loom. Several weaves are possible on this loom, but the one that admits of the widest variations is the so-called ‘four harness overshot weave,’—and this is the foremost of the colonial weaves.” So wrote Mary Meigs Atwater in The Shuttle-Craft Book of American Hand-Weaving when speaking of the American coverlet and the draft s most loved by those early weavers.

Overshot, in my mind, is the most North American of yarn structures. Yes, I know that overshot is woven beyond the borders of North America, but American and Canadian weavers of old took this structure and ran with it. The coverlets woven by weavers north and south provided those individuals with a creative outlet. Coverlets needed to be functional and, ideally, look nice. With (usually) just four shaft s at their disposal, weavers gravitated toward overshot with its stars, roses, and other eye-catching patterns. Using drafts brought to North America from Scotland and Scandinavia, these early weavers devised nearly endless variations and drafts, giving them delightful names and ultimately making them their own.

When I first began designing my overshot scarf, I used the yarn color for inspiration and searched for a draft reminiscent of poppies. I found just what I was looking for in the Ancient Rose pattern in A Handweaver’s Pattern Book. When I look at the pattern, I see poppies; when Marguerite Porter Davison and other weavers looked at it, they saw roses. I found out later that the circular patterns—what looked so much to me like flowers—are also known as chariot wheels.

If you"ve always wanted to learn to weave, but didn"t know where to begin, this is the video for you. This course is designed to acquaint you with the basics and help you choose a direction in which to begin. It starts with an overview of what handweaving is, what can be woven, plus a look at several types of looms and how they work. You will become acquainted with a number of small tools used by weavers, as well as the vocabulary of weaving terms needed to understand the process. You"ll learn about warp and weft yarns, and how their size, weight, elasticity and fibre content relates to specific projects and fabrics. The detailed exercise in figuring out how much warp and weft is needed for a project will become a valuable resource as you continue with future weaving projects. You will also learn how to prepare (measure) the warp using a warping board. This course is recommended as a prerequisite to other video weaving courses for those who are new to weaving. An exciting new hobby awaits you!

This book features the original sample collection and handwritten drafts of the talented, early 20th century weaver, Bertha Gray Hayes of Providence, Rhode Island. She designed and wove miniature overshot patterns for four-harness looms that are creative and unique. The book contains color reproductions of 72 original sample cards and 20 recently discovered patterns, many shown with a picture of the woven sample, and each with computer-generated drawdowns and drafting patterns. Her designs are unique in their asymmetry and personal in her use of name drafting to create the designs. Bertha Hayes attended the first nine National Conferences of American Handweavers (1938-1946). She learned to weave by herself through the Shuttle-Craft home course and was a charter member of the Shuttle-Craft Guild, and authored articles on weaving.

As I began to plan the structure of the piece I knew that using an overshot technique for my weaving would probably give me the visual texture that I desired.

The overshot technique in weaving is accomplished by using two different thickness ofthread alternated in the weaving rows. The pattern row is made using the thicker of the two threads and usually skips over several threads to achieve the desired pattern that you are weaving. The thinner of the two threads is woven across the warp before and after each thicker pattern thread to “lock in” the pattern thread. The thinner threads are woven in tabby (weaving speak for plain weave).

I feel that using the overshot weaving technique helped me to capture the textual feeling I wanted for this runner. Here is how the project progressed and a list of the yarns that were used.

For the warp threads (threads going from the front to the back of the loom) and the tabby threads I used a dark brown cottolin yarn. Cottolin yarn is made from 60% cotton and 40% linen. The pattern thread used was an 8/4 cotton yarn. The 8/4 refers to the size of the yarn. The cotton yarn was about twice as thick as the cottolin yarn, thus the raised overall textural look and feel in the runner.

With the color pallet and types of yarn I chose and using the overshot technique, I felt like I was able to achieve the look that I wanted for this project. What do you think??

Half way through my weaving I decided I wanted to add a little something special to the piece that would bring the cultural influence in the tribal shield that inspired me to create this project to begin with. As I searched for that special something, I found a vendor on Etsy that imported fair trade beads from Africa. Handmade metal and hand-carved bone beads. I was pretty excited! Special handmade beads from another artist to compliment a handmade runner, just what the runner needed forthat finishing touch. When the beads arrived I laid them out on the runner that I was almost finished weaving and knew it was definitely the perfect accent!

Adding the beads to the finished runner was a long and tedious task but definitely worth the work, time and effort when I saw the finished project!! Once the beading was finished all that was left was to do the finishing wash and block drying and trimming off any overlapped threads in the weaving.

I actually had some beautiful brass and bone beads leftover from my weaving projects so I made those into some fun jewelry pieces . I’ll have some pictures of those in my next blog post.

The exhibition Politics at Home: Textiles as American History, in the Ruth Davis Design Gallery, features several woven coverlets from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; these domestic textiles helped establish the graphic language of American politics through both geometric and figured weaving patterns. These historical patterns continue to inspire the art and craft of weaving today. This online program will feature a brief virtual view of historical woven coverlets from the Helen Louise Allen Textile Collection and a conversation with Marianne Fairbanks, Assoc. Professor of Design Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Justin Squizzero, founder of The Burroughs Garret, whose own practices today respond in varied ways, with varied tools, to the artifacts and print sources of historical American weaving.

I thought, why not… two weeks on a big adventure all by myself, driving across the country in my brand new Chevrolet Chevette rocking on to the Doobie Brothers… what could be better than that. And after all, I had woven a set of placemats, an entire Overshot coverlet without alternating tabby picks between pattern picks and a blanket that stood up in the corner all by itself. I was sure I could handle a Multi-Harness loom or anything else that came my way.

I should have realized that summer that I had an angel on my shoulder guiding my every movement because Mary Andrews accepted me into her workshop and my life was forever changed.

Mary was formidable. Her knowledge and her presence demanded respect and I held her in awe. I was very nervous… she was a tad stern and I was… well ‘me’!

I was the youngest person in the room, an aspiring hippie and remember… had woven exactly one set of placemats, one overshot coverlet without any tabby and a blanket that could have been used as a sheet of plywood… I might add that each of those projects were the most remarkable weaving I had ever seen up to that point. Within moments I was scared to death.

Mary’s class was formatted so that she lectured in the morning and we wove in the afternoon. I learned so much in the next two weeks… Mary taught me how to do read patterns, how to do draw-downs, how to hemstitch, how to do name drafts in overshot and that overshot had alternating tabbies between pattern picks :A), she taught me how to sit at the loom properly, how to hold a shuttle, how to control my selvedges. She taught me what the numbers mean in 2/8, what cellulose and protein fibres were. She gave us graphs with so much information crammed into them, sett charts, yardage charts, reed charts. She taught me the Fibonacci numerical series and the Golden Mean. In two weeks she crammed everything she could into my little brain and I learned that I could weave anything if I could read a draft.

She taught me the four P’s: with Patience and Practice you Persevere for Perfection. I have quotes she shared with us all through my book, “I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand”.

Mary Andrews was a gem, she was the weaving worlds national treasure, she was a flower of Alberta. Her greatest gift was her ability to share her knowledge which she did with grace and kindness.

Bom in Montreal Quebec in 1916, Miss Andrews affinity with the “Comfortable Arts” was apparent at an early age. At the age of 23 while working as a senior counsellor at Taylor Statten Camp in Ontario, she was exposed to the craft of handweaving. On her return to Oshawa in 1939 she immediately bought the first of her 11 looms and began a life long study. Through correspondence with Harriet Tidball of the United States, Mary studied textile theory and cloth construction.

From 1943-1948, Mary set up the Ontario Government Home Weaving Service, an agency designed to revive handweaving and encourage a cottage industry. Along with two other weaving teachers she taught and developed the project throughout Ontario. During the last year of this programme Mary continued her own studies at the Penland School of Handcrafts in North Carolina, USA.

In 1948 Mary was appointed Assistant Programme Director for the YWCA in Oshawa. She spent the next six years teaching handweaving, leatherwork and metalwork to hundreds of students. It was during these years that Mary first travelled west to study at The Banff School of Fine Arts with two of Canada’ finest weavers, Ethel Henderson and Mary Sandin. It was during these visits that her desire to reside in Alberta was kindled.

Mary joined the Canadian Red Cross in 1954 and served as a Rehabilitative Therapist in Korea and Japan after the Korean War. After working for 18 months on a Welfare Team she travelled through 13 countries working her way back to Canada in 1958.

On her return to Canada she was appointed Director of Handcrafts at the Grenfell Labrador Medical Mission. She travelled throughout Northern Newfoundland and Labrador teaching handweaving, embroidery and traditional rug hooking to its residents with the intent of developing cottage industries that could subsidize the fishermen’s incomes. She remained in Labrador until September of 1962 when she purchased her home in Banff and realized her dream of living in Alberta.

From 1962-1975, Mary taught at The Banff School of Fine Arts where she developed the programme from a six week summer course to a two year Diploma granting programme. Through her early guidance and insistence that Visiting artists be brought from around the world, the Fibre Department became a widely renowned centre of study for the Textile Arts.

Mary retired from The Banff Centre in 1975 and spent another five years teaching and lecturing all over Western Canada. In 1984 she developed a four year summer weaving programme for Olds College where her students prepared for the Canadian Guild of Weavers, Master’s exams.

One of Mary’s greatest personal achievements was earning her Master Weavers certification from the Guild of Canadian Weavers in 1972 and she later published her Master’s Thesis “The Fundamentals of Weaving” with book three finished in 1994. Throughout this massive three volume endeavour she was assisted by Ruth Hahn who provided all of her IT support.

She also spent a great deal of time serving the community of Banff by working in the Banff Library several mornings a week and donating her weaving for auction to raise funds for community projects. In her late seventies she was still taking courses in English Literature and Philosophy from Athabasca University.

I wove a few yards of fabric in shadow weave using woolen yarns I found in my stash, and from this fabric I made myself a new pullover. I haven’t made a new one in a long time because the old ones seem to last forever! Shadow weave seemed like a good choice because its mostly plain weave structure would work well with these yarns to produce a lightweight, felted fabric after wet finishing, and also because there are so many patterns you can design in shadow weave by alternating light and dark or contrasting colors of yarns. Shadow weave falls under the category of color-and-weave and is considered to be a color-and-weave effect.

In this post I’ll be sharing photos, drafts, and notes about a couple of shadow weave samples and the pullover. I wove a sample in cotton yarn, liked the pattern a lot and decided to use it to weave the fabric for the pullover as well. Here’s a photo of the sample:

I developed the weaving draft for this shadow weave pattern that to me looks like a plaited twill, from Fig. 586 in G. H. Oelsner’s A Handbook of Weaves (downloadable at handweaving.net), described by Oelsner as a twill “arranged to produce basket or braided effects.” However, I did not weave this draft as a twill but used it as a 7-block profile draft:

I wrote an article in the June 2008 issue of the Complex Weavers Journal, “Shadow Weave & Log Cabin,” that describes the method I used for designing shadow with independent blocks. That’s the method I used to develop this 14-shaft thread-by-thread shadow weave draft from the 7-block profile draft:

The red and white contrasting colors work well in the woven sample to show off the plaited/braided pattern. The colors of the woolen yarns I had available were not as contrasting, but since I wanted an understated look for my pullover I hoped it would look nice anyway and here it is:

Notes on weaving the fabric for the shadow weave woolen pullover: I used a 2-ply heathery purple/blue woolen yarn (272 yds./4 oz. skein, “Regal” from Briggs & Little Woolen Mills) and a beautiful, single-ply brown/black woolen yarn, I’m not sure where I bought it years ago, the label says on it “Black Welsh, 1/5-1/2 YSW.” These two yarns alternate in the warp and the weft at a sett of 8 e.p.i. and about the same p.p.i. The width of the web on the loom was 28 inches and the total woven length about 3-1/4 yards. I wet finished it in the washing machine in warm/hot water with Ivory for wool, agitated only two minutes, rinsed, and carefully spin dried it. I put it in the dryer on low heat for about 12 minutes and then let it air dry until it was completely dry. The end result was a slightly felted, lightweight fabric, 22 inches wide and 3 yards long. The construction of the pullover was fairly easy because of its simple design. I cut out the pieces, serged the raw edges, sewed the pieces together and knitted the hem, collar, and cuffs. By the way, Laura Fry is an expert on wet finishing and I treasure her book, Magic in the Water, with real woven swatches attached, great tips, and excellent information. For more about weaving with woolen yarns see one of my older posts, 2/2 Twill: Handwoven Woolen Wearables.

There are other methods of designing shadow weave than the method of using independent blocks of log cabin that I used to design the pattern for the red and white sample and the pullover. The Atwater method uses alternate threads for the basic pattern and the threads that form the “shadow” are threaded on the opposite shaft. The Powell method uses a twill-step sequence and two adjacent blocks weave together in the pattern. Carol Strickler explains it in detail in A Weaver’s Book of 8-Shaft Patterns in Chapter 6 on shadow weave. She writes about Mary M. Atwater who introduced shadow weave in the 1940’s and Harriet Tidball and Marian Powell who later developed other methods for designing the same fabric.

I like to design shadow weave the Atwater way with the help of my weaving software (Fiberworks PCW). I simply design a threading and/or treadling profile and use the extended parallel repeat to generate a complete draft with the Atwater tie-up. Below are a photo of an 8-shaft shadow weave sample and two versions of its draft that I designed and wove, similar to pattern #8-16-1 in Marian Powell’s book, 1000(+) patterns in 4, 6, and 8 Harness Shadow Weaves. I designed the Atwater method draft first by using the extended parallel repeat and then used the shaft shuffler to rearrange the shafts to come up with the Powell method draft with the Powell tie-up. These two methods produce the same results:

Season’s Greetings and a happy and healthy New Year to my readers who visit from all corners of the world! Thank you for visiting and wandering around in my weaving universe!

8613371530291

8613371530291