overshot rug manufacturer

Overshot is a weave structure traditionally used for patterning coverlets. It is wonderful for table runners and placemats and other applications where a decorative fabric can be used. Pillows and throws can be woven using overshot and with the proper yarns and careful planning overshot works well as a tough little scatter rug. If you have never woven overshot before this is a great first time introduction to this weave structure. Students will weave rugs on pre-warped looms. Each student will be able to weave two small rugs. The looms will be threaded to two different overshot patterns. One group will be threaded to Star of Bethlehem and the others to a single Snowballs pattern. You can choose to weave on one loom for both rugs, or trade with another students to weave a rug in a different pattern. Either way you will love your rugs. All materials included with tuition.

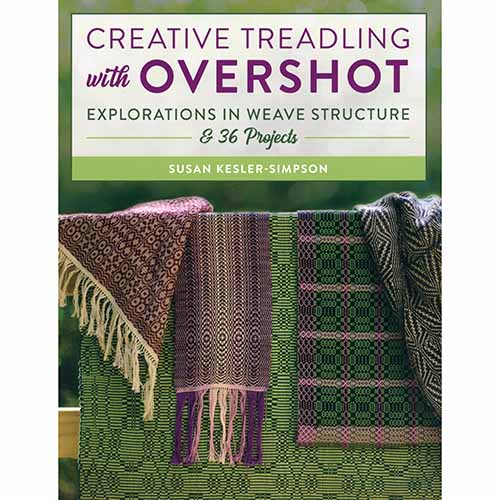

By Susan Kesler-Simpson. Overshot can seem overwhelming if you haven"t done it before but don"t be daunted! Susan Kesler-Simpson"s book makes overshot very approachable. The first part of the book covers what makes overshot what it is structurally. Then Susan goes over ways to adapt overshot: creating your own design from an existing pattern, adding borders, and combining different threading and treadling sequences. She offers tips for making the process of threading and treadling easier. And then the projects! Thirty-seven different projects are given, with large charts for threading and treadling, photos of the finished pieces, and close-up photos showing the structure. The projects allow you to apply what you have just learned and explore the range of possiblities with overshot.

By Susan Kesler-Simpson. You may be familiar with overshot in its traditional form--four harness threading and two wefts alternated while harnesses are lifted in pairs. But it doesn"t have to be that way! Susan Kesler-Simpson has explored the possibilities of a traditional overshot treadling but paired with unconventional treadling sequences drawn from summer & winter, crackle, shadow weave, Bronson lace, and more. In this book, she presents each variation with diagrams and text to describe its interlacement. Two projects for each variation apply the technique. The text is accompanied by many color photos showing the full project as well as close-ups of the fabric.

Overshot: The earliest coverlets were woven using an overshot weave. There is a ground cloth of plain weave linen or cotton with a supplementary pattern weft, usually of dyed wool, added to create a geometric pattern based on simple combinations of blocks. The weaver creates the pattern by raising and lowering the pattern weft with treadles to create vibrant, reversible geometric patterns. Overshot coverlets could be woven domestically by men or women on simple four-shaft looms, and the craft persists to this day.

Summer-and-Winter: This structure is a type of overshot with strict rules about supplementary pattern weft float distances. The weft yarns float over no more than two warp yarns. This creates a denser fabric with a tighter weave. Summer-and-Winter is so named because one side of the coverlet features more wool than the other, thus giving the coverlet a summer side and a winter side. This structure may be an American invention. Its origins are somewhat mysterious, but it seems to have evolved out of a British weaving tradition.

Multi-harness/Star and Diamond: This group of coverlets is characterized not by the structure but by the intricacy of patterning. Usually executed in overshot, Beiderwand, or geometric double cloth, these coverlets were made almost all made in Eastern Pennsylvania by professional weavers on looms with between twelve and twenty-six shafts.

America’s earliest coverlets were woven in New England, usually in overshot patterns and by women working collectively to produce textiles for their own homes and for sale locally. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book, Age of Homespun examines this pre-Revolutionary economy in which women shared labor, raw materials, and textile equipment to supplement family incomes. As the nineteenth century approached and textile mills emerged first in New England, new groups of European immigrant weavers would arrive in New England before moving westward to cheaper available land and spread industrialization to America’s rural interior.

Southern coverlets almost always tended to be woven in overshot patterns. Traditional hand-weaving also survived longest in the South. Southern Appalachian women were still weaving overshot coverlets at the turn of the twentieth century. These women and their coverlets helped in inspire a wave of Settlement Schools and mail-order cottage industries throughout the Southern Appalachian region, inspiring and contributing to Colonial Revival design and the Handicraft Revival. Before the Civil War, enslaved labor was often used in the production of Southern coverlets, both to grow and process the raw materials, and to transform those materials into a finished product.

The first coverlet below is complete and woven in a species of the overshot structure. I have not seen another one like it but Melinda Zongor, who heads the coverlet museum in Pennsylvania, says that it is a familiar one.

The next piece was one of two coverlets a member of the audience brought in. Both are done in the overshot structure. Both are indicated to be family coverlets woven in southwest Virginia. Undated. Both were oven in two pieces and then sewn together. The center seam is visible.

The piece below is a scarf, not a coverlet, but also woven in an overshot weave. Notice how similar the pattern and coloring in this scarf is to that in the coverlet above.

The fragment below is one of two (from the same coverlet) I had in the room that are done in the summer-winter weave. The summerwinter weave has only a single set of warps but, this one, has a heavier handle than do most of the overshot (and the C8 beiderwand) examples we’ve seen above.

One of the problems with such signatures is that they can be added afterward with more favorable information on them. Of course, this is a problem with pile rugs, as well.

“This quilt was inspired by a wool embroidered and appliqued rug in the collection of the American Folk Art Museum in New York. It is thought to have been made around 1860 in either New York or Maine, by an unknown artist. The quilt is hand appliqued and hand embroidered using mostly solid colored cotton fabrics, with a few tone on tone prints. The colors in the quilt are similar, but not identical to those in the rug. This is not an effort to duplicate the rug, but the relationship will be clear to anyone seeing both pieces. Since the applique is so dense there is not much room for creative quilting, so it is in the process of being hand quilted in a basic grid pattern.”

Now we moved to our final group of the day. Hooked rugs. You may have to worry about aesthetic decompression as you move from Barbara’s magnificent applique quilt, above, to my humble hooked rug below. But let’s be brave about that.

You saw this piece in the lecture and can see why it is called “a poor man’s rug.” It is a little over 4′ X 6′ and heavy. It has been, and despite condition problems, still could be used on the floor. As we said in the lecture, you can see that the maker was envious of an oriental rug and determined to have something like one. The thickish black lines mark off putative borders and a central medallion on the basic “marbling” of the rug. Despite it being humble, it projects good graphic punch.

One experienced collector said to me that he felt that the maker of this rug should have retained the same striped colors, and their order of use, in the interlacing bands. He experienced this inconsistency as an aesthetic fault. I acknowledge the fact of what he says, but find that this inconsistency works differently for me, and, in fact, enriches the aesthetic impact I experience looking at this fragment.

Notice that it’s actually a symmetric knot, tied on one horizontal part of a hole in the backing material rather than (as is the case with most hand woven pile rugs) around two warps. (Amy checked and, sure enough, the stitches in her hooked rug are of the knot variety that confirms that it is a latch hooked rug.)

Notice also that with a latch hooked rug the stitches (knots) are entirely independent of one another. There is no continuation stitch to stitch on the back side that often occurs with conventionally hooked rugs (see image below).

A second point about the backing in H42b is generally true of hooked rugs and the backings used for them. The the holes visible in H42b are sizable. Here it is again for ease of comparison.

The general point to be made is that a hooked rug can have fewer stitches than the number of holes in the backing material (and Michael Heilman says that is usual), but not more. The number of holes per linear inch in the backing material determines the maximum fineness a hooked rug can have.

Michael said that Rug 46 “…is basically a hand dyed wool fabric rug I made with a shuttle hook, using 1/4” strips.. There are also sections of dyed wool yarn scattered throughout. I guess you would term the design “hit-or-miss” in the same sense of a quilt made with miscellaneous pieces. It is about 28″ x 42″. Rug 46 is a finely made wool rug constructed of 1/8 wide fabric strips on a cotton backing.”

Michael: “H47, the flower pattern is fairly conventional, but well done. My guess is that this rug dates from the 1920s or 30s and that it was stored away for most of its life., showing no signs of wear or fading.

Normally, a rug maker leaves about 2 or more inches of unworked backing fabric around the edge and then folds that over when finished and sews that portion to the back.

Thanks, too, to Michael Heilman, who hooks and collects hooked rugs, and teaches the hooking of them. Michael provided support during our preparations of the hooked rugs part of this program, brought hooked rugs he had made or collected, and helped with our describing the hooked rugs brought in.

While linoleum manufacturers cornered the market in kitchens and baths with plain-Jane patterns, by 1929 competitors were invading living and dining rooms with colorful “rugs” that had never seen a loom and were not necessarily even linoleum. (Images: James C. Massey archives)

Conniving one material to imitate another is a great tradition in old houses, from manipulating paint into faux wood graining, or plaster into ersatz marble, to simulating the structural joinery found in many Craftsman-style Arts & Crafts houses. Yet for sheer practicality, not to mention amusement value, can there be any finer form of fakery than the linoleum rug? Imagine, all the visual loveliness of a woven carpet without the vacuuming, shampooing, and worrying about spills—just damp-mop and you’re done!

Although most of the linoleum sold up to the 1960s was probably installed wall-to-wall in kitchens, bathrooms, and public buildings, there was enough demand for rugs that every company’s catalog devoted a healthy batch of pages to them. Should you wonder if make-believe rugs are tacky today, have no fear. That’s what makes them so fabulous! Here’s what linoleum rugs and their look-alikes are all about and what to do if you find one in your old house.

What separates a linoleum rug from regular linoleum? Not much, beyond the fact that the typical rug is a movable rectangle with a border. Many manufacturers made the same patterns as both wall-to-wall products and rugs, but the latter would also incorporate some sort of design around the edges. In addition, they tended to sell the rugs in standard rug sizes—4’x6′, 5’x7′, 6’x9′, 8’x9′, up to 12’x 15′. Rugs also came as mats (generally 2’x3′) for placing in front of the sink. Beyond this, linoleum rugs don’t always have to look like textiles, and they don’t even have to be linoleum.

With a deft promotional spin, Congoleum made a virtue of rug patterns that were only paint-deep, promising “freedom from tiresome housework” because they could be “cleaned in a wink with a few strokes of a damp mop.”

The evolution of the linoleum rug begins with the invention of linoleum by the Englishman Frederick Walton in 1863. Initially, linoleum came in solid colors, although soon after Walton debuted his wonder flooring, he developed marbleized, granite, and jaspé linoleum. By 1892, Walton had introduced two ways to make patterned linoleum: stencil inlaid and straight-line inlaid. Linoleum could also be decorated by hand-block printing with wood blocks —the same methods used to decorate floorcloths, the ancestors of linoleum—and this is the method primarily used to make linoleum rugs.

In 1910 American linoleum producers suddenly faced a competing product that wasn’t linoleum at all. Called Congoleum, a contraction of Congo (the country that was a major source of asphalt) and linoleum, the flooring was an asphalt-saturated felt known generically as felt-base. When printed on the surface in oil paint with a linoleum-like design, felt-base looked just like linoleum, and it was cheaper than the real thing by a third. Initially, felt-base rugs were printed by hand using wood blocks in much the same fashion as printed linoleum, an expensive process. Only felt-base rug borders (generally printed to resemble wood flooring) were printed by machine. Within a couple years, though, the Congoleum Company decided to invest in a rotary press, and its first machine-printed rug came off the production line around 1913.

In 1927 Armstrong advertised its Genuine Cork Linoleum Rugs as a colorful flooring alternative for kitchens, be it this fanciful Japanese pattern or the standard grained look of jasper.

When felt-base was first introduced, linoleum manufacturers fought back, urging consumers to learn how to tell genuine linoleum: look for the woven burlap back. To add to the confusion, felt-base makers coated the back of their rugs with the same red iron oxide that linoleum manufacturers used on the back of linoleum. Nonetheless, the Armstrong Company, a leading linoleum producer, experimented with felt-base starting in 1916, producing Fiberlin rugs and flooring. In 1917 they introduced linoleum rugs, which sold so well they dropped the Fiberlin line in 1920. But a few years later they bought out the Waltona Company, another felt-base manufacturer, and began offering felt-base again in 1925. The Waltona line was renamed Quaker Rugs, and Armstrong stopped selling the real linoleum rugs after that.

Congoleum sold their rug product under the Gold Seal label. Other companies also got into the resilient rug business, both linoleum and felt-base, including Sloane, Blabon, Pabco, and Dominion (Canada). Some continued to offer both products even after the larger companies (Armstrong and Congoleum-Nairn) had stopped making linoleum rugs and only sold the felt-base merchandise. In general, by the late 1920s, most resilient flooring rugs were felt-base instead of linoleum. Felt-base rugs (and flooring) continued to be produced well into the 1950s.

Since these products were marketed as rugs, it’s no surprise they were often printed to resemble various kinds of woven or knotted carpets. Some even had printed fringe for full effect. The most amusing of these were based on traditional oriental rugs, though there were also fake braided rugs, rag rugs, and needlepoint rugs. Straw or other fiber matting was another fashionable motif—and easier to keep clean than the real thing!

Little more than borders and a floral pattern, such as this Chrysanthemum design, were necessary to turn functional flooring into a rug fit for a living room.

At least as popular as florals were all sorts of geometric patterns, from tile-like compositions to designs that were termed jigsaw, random tile, and overshot interliners. Geometrics could either be printed as an all-over pattern, or on a background that vaguely resembled marble, clouds, or a pointillist painting. Many rugs also imitated the typical marble linoleum flooring with inlaid borders of solid color or contrasting marbleized colors. Patterns resembling wood were most often sold for use as rug borders, although rugs with patterns mimicking parquet were advertised for use in formal rooms (a bit of wishful thinking on the manufacturers’ part, perhaps). Though wood patterns always look fake to our eyes, don’t let it bother you; as with country wood-graining, embrace the fakeness.

Almost all manufacturers continued making rugs into the 1950s, running modern and atomic patterns in their catalogs right along with pages of ersatz originals.

During the 1930s and ’40s, there were even a couple of full-on Art Deco/Moderne/Streamline rug patterns, though not as many as one might have liked to see. Similarly, in the 1950s there were a few designs that really screamed mid-century Modern. Nonetheless, the 1950s wasn’t really as modern as we think it was, and there were many more hokey florals and fake braided rugs than there were Space Age/boomerang/kidney-shaped patterns. More’s the pity.

What are almost exclusively the province of linoleum or felt-base rugs, however, are patterns meant for kitchens or nurseries. Kitchen rugs featured vegetables and fruits, dishes, coffee and tea pots, chickens, fish, cows, and the like. Nursery rugs used motifs such as nursery rhyme characters, game boards, cute baby animals, cowboys, spaceships, maps, or the circus.

In their heyday, felt-base and linoleum rugs were most often used in bedrooms, covered porches, and attic living spaces. Sometimes they popped up in dining rooms, and you may uncover one while taking up wall-to-wall carpeting. If you’re very lucky, you may discover a never-used rug, still rolled up, stashed in the attic, basement, or garage. Or you may find rug sections lining the bottom of a closet or a drawer. These are pieces of history and shouldn’t just be tossed into the trash.

An old linoleum or felt-base rug is worth appreciating because it is unlikely this product will ever be made again. The few companies now producing real linoleum don’t offer patterns, let alone rugs, and no one makes felt-base flooring anymore. The closest you can get is a floorcloth, a pre-linoleum technology, these are usually custom-made and not cheap. So if you have a linoleum rug, treasure it, even if your friends don’t understand.

When I was a kid my Oma had a rag rug in front of her kitchen sink and I remember the pleasure of looking down and wondering how all those colors and textures had been put together. Now that I weave, I understand how that long-ago rug was made—and can create the magic for myself on the loom. Not just a scrappy leftover, rag rugs can be practical everyday textiles or incredible works of art—and are a great way to use up yarns like Mallo and Beam in your stash.

Rag rugs are comprised of two different parts: a yarn warp, and a rag weft. At their most basic, a rag rug is woven in plain weave, making them easy to try on your rigid heddle loom. But you don’t have to stick to plain weave—many of the prettiest rag rugs I’ve seen use twills or other structures to create pattern or texture.

Because the size difference between the warp and weft is not even (the rags being the thicker of the two), rag rugs are generally woven with a more open sett. This means you see more weft than you do warp. This isn’t always the case, however—the Viken Trivets are an excellent example of repp weaving, where the warp is sett very densely to completely cover the weft. The Viken Trivets use yarn, instead of rags, as the weft, but could quite easily be made using thin rag strips too.

The key to weaving rag rugs is a strong and sturdy warp thread. The warp needs to be able to travel around the thick rag weft and withstand the rigors of increased tension, weaving and beating. In all of the old rag rugs I’ve seen, the warp is always the part that fails first, so choosing something strong will help your finished rug stand the test of time.

Rag rugs are usually beat very firmly so that the fabric strips are tightly packed in, and a firm beat often translates into extra strain selvedges, especially those that are thin or loosely spun. For this reason, most weaving books recommend using a temple when you weave a rag rug (though you can, of course, weave without one too!).

While a plain white cotton warp is the classic choice, a rag rug warp is an opportunity to have fun with color! Use your warp to empty bobbins, mix textures, and add stripes.

Rag rug wefts are strips of already woven cloth. As the name suggests, they were likely once made using rags—cloth that had already been woven, worn, and used past its best. Cut or torn into strips, this cloth was then repurposed to live on a little longer as thick rugs, bedcovers, clothing, and other home goods.

This element of recycling is what really excites me about weaving rag rugs. My favorite place to get fabric to repurpose into rugs is at thrift stores, where an incredible amount and selection of prints and patterns can be found in the bed sheet aisle. While I prefer using woven fabric to create rag rugs, you can also use knits too.

The width of the fabric strips are up to you and will have an effect on the scale of your rug. I use strips between 3/4-1” wide, but one of my favorite rugs has fabric strips closer to 1/2”. When it comes to joining two lengths of rag weft together, there are a few ways to do it—I prefer to cut my ends on a diagonal and overlap them manually in my shed, but other weavers prefer sewing them together.

Can you use Gist yarns to make rag rugs? The answer is yes! For this article I tried out three yarns: Beam, Duet, and Mallo. I made three small samples on two different warps.

For my first sample, I used Beam and Duet in my warp. Having made a few woven rag rugs, I knew Beam’s smooth and strong nature would be excellent for a rag rug, but I wondered about Duet, because it has a looser twist. This twist makes it wonderful for scarves, kitchen towels, and other projects, but I didn’t think it would stand up to the firm beat needed on my table loom. I used a 1 end Beam in Lemon, 1 end Duet in Dune pattern and sett my sample at 10 epi.

As I predicted, the left side selvedge, which was Duet, broke just as I finished weaving the sample. The Beam side didn’t show any significant wear and tear. Perhaps if I was making a wider piece and using a temple I could get away with using Duet as my rag rug warp, but for beginner rag rug makers, I would suggest you stick with Beam!

For my second and third samples, I used Mallo in Brick and sett it at 12 epi. Mallo was a lovely rag rug warp—strong and easy to weave, the thick and thin texture gave the samples a lovely visual effect. To show you just how much the weft colors affect the finished project, I made two samples: one with a dark blue and red rag, the second with a light blue and white striped rag.

Rag rugs make for excellent strong and unique woven rugs for your home. I have one next to my bed, but I also use one as a bath mat and one in the kitchen too. Because they"re easy to wash, a woven rag rug is great to have around the house.But there"s a lot of other uses for this type of weaving too.

What I love so much about weaving rag rugs is that there’s an element of unpredictability—how the warp, weft, weave structure, and scale work together makes the weaving very exciting and fun. For inspiration and further reading, there are two books I have enjoyed and would recommend: Weaving Contemporary Rag Rugs by Heather Allen (which is sadly out of print, but available through book resellers)and Tina Ignell’s Favorite Rag Rugs.

One major way to classify watermills is by wheel orientation (vertical or horizontal), one powered by a vertical waterwheel through a gear mechanism, and the other equipped with a horizontal waterwheel without such a mechanism. The former type can be further divided, depending on where the water hits the wheel paddles, into undershot, overshot, breastshot and pitchback (backshot or reverse shot) waterwheel mills. Another way to classify water mills is by an essential trait about their location: tide mills use the movement of the tide; ship mills are water mills onboard (and constituting) a ship.

There are two basic types of watermills, one powered by a vertical-waterwheel via a gear mechanism, and the other equipped with a horizontal-waterwheel without such a mechanism. The former type can be further divided, depending on where the water hits the wheel paddles, into undershot, overshot, breastshot and reverse shot waterwheel mills.

The Greeks invented the two main components of watermills, the waterwheel and toothed gearing, and used, along with the Romans, undershot, overshot and breastshot waterwheel mills.

Most watermills in Britain and the United States of America had a vertical waterwheel, one of four kinds: undershot, breast-shot, overshot and pitchback wheels. This vertical produced rotary motion around a horizontal axis, which could be used (with cams) to lift hammers in a forge, fulling stocks in a fulling mill and so on.

An inherent problem in the overshot mill is that it reverses the rotation of the wheel. If a miller wishes to convert a breastshot mill to an overshot wheel all the machinery in the mill has to be rebuilt to take account of the change in rotation. An alternative solution was the pitchback or backshot wheel. A launder was placed at the end of the flume on the headrace, this turned the direction of the water without much loss of energy, and the direction of rotation was maintained. Daniels Mill near Bewdley, Worcestershire is an example of a flour mill that originally used a breastshot wheel, but was converted to use a pitchback wheel. Today it operates as a breastshot mill.

Larger water wheels (usually overshot steel wheels) transmit the power from a toothed annular ring that is mounted near the outer edge of the wheel. This drives the machinery using a spur gear mounted on a shaft rather than taking power from the central axle. However, the basic mode of operation remains the same; gravity drives machinery through the motion of flowing water.

A different type of watermill is the tide mill. This mill might be of any kind, undershot, overshot or horizontal but it does not employ a river for its power source. Instead a mole or causeway is built across the mouth of a small bay. At low tide, gates in the mole are opened allowing the bay to fill with the incoming tide. At high tide the gates are closed, trapping the water inside. At a certain point a sluice gate in the mole can be opened allowing the draining water to drive a mill wheel or wheels. This is particularly effective in places where the tidal differential is very great, such as the Bay of Fundy in Canada where the tides can rise fifty feet, or the now derelict village of Tide Mills, East Sussex.Eling, Hampshire and at Woodbridge, Suffolk.

Growing up influenced by her grandparents home filled with art, Scandinavian Röllakan wallhangings, British wallpapers and craft and textiles from her grandmothers childhood in Ethiopia layed the foundation for a style both Scandinavian and global. After studies and work in Berlin, Copenhagen and London with a Master in woven textiles from Royal College of Art, Maja moved to Sweden to work with Gunilla Lagerhem Ullberg at Kasthall. Maja has since 2013 designed rugs and collections for Kasthall and world wide market in both tufted and woven qualities. She has worked in projects with designers and architect to create tailor-made solutions for the textile floors for spaces like restaurants, hotels, offices, fashion houses and their retail spaces.The source of inspiration is often textile tradition , archives and art while painting, creating and sampling on the loom is often the primary starting point for a new design.

Since 2020 Maja is working from her own studio to explore weaving and making further. She has designed two rugs for Vandra with a starting point in the color of their yarns and ability to freely hand weave.

The creative process was sketching in watercolour with blocks of lines and objects inspired by light through a window creating shadows in a room, tactile memories and a mix of stillness and movement. The result was Alba av Vera, two modern woven rugs in rödlakan technique.

8613371530291

8613371530291