overshot weaving drafts quotation

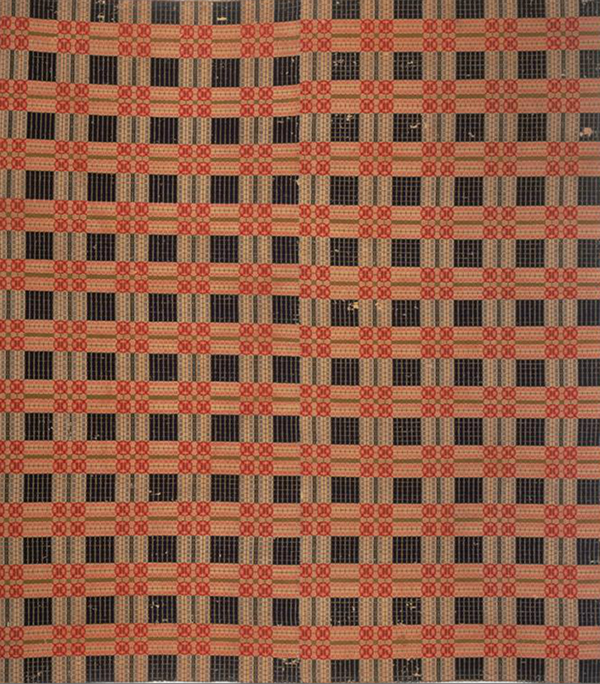

Woven by Rachel SnackWeave two overshot patterns with the same threading using this downloadable weave draft to guide you. This pattern features the original draft along with one pattern variation. Some yarns shown in the draft are available to purchase in our shop: 8/2 cotton, wool singles, 8/4 cotton (comparable to the 8/4 linen shown).

please note: this .pdf does not explain how to read a weaving draft, how to interpret the draft onto the loom, or the nuances of the overshot structure.

I wove some samples and decided to make this for my scroll. The warp was handspun singles from Bouton. I wanted to see if I could use this fragile cotton for a warp. I used a sizing for the first time in my weaving life. The pattern weft is silk and shows up nicely against the matt cotton.

This illustration and quote are in The Weaving Book by Helen Bress and is the only place I’ve seen this addressed. “Inadvertently, the tabby does another thing. It makes some pattern threads pair together and separates others. On the draw-down [draft], all pattern threads look equidistant from each other. Actually, within any block, the floats will often look more like this: [see illustration]. With some yarns and setts, this pairing is hardly noticeable. If you don’t like the way the floats are pairing, try changing the order of the tabby shots. …and be consistent when treadling mirror-imaged blocks.”

The origin of the technique itself may have started in Persia and spread to other parts of the world, according to the author, Hans E. Wulff, of The Traditional Crafts of Persia. However, it is all relatively obscured by history. In The Key to Weavingby Mary E. Black, she mentioned that one weaver, who was unable to find a legitimate definition of the technique thought that the name “overshot” was a derivative of the idea that “the last thread of one pattern block overshoots the first thread of the next pattern block.” I personally think it is because the pattern weft overshoots the ground warp and weft webbing.

Overshot gained popularity and a place in history during the turn of the 19th century in North America for coverlets. Coverlets are woven bedcovers, often placed as the topmost covering on the bed. A quote that I feel strengthens the craftsmanship and labor that goes into weaving an overshot coverlet is from The National Museum of the American Coverlet:

Though, popular in many states during the early to mid 19th centuries, the extensive development of overshot weaving as a form of design and expression was fostered in rural southern Appalachia. It remained a staple of hand-weavers in the region until the early 20th century. In New England, around 1875, the invention of the Jacquard loom, the success of chemical dyes and the evolution of creating milled yarns, changed the look of coverlets entirely. The designs woven in New England textile mills were predominantly pictorial and curvilinear. So, while the weavers of New England set down their shuttles in favor of complex imagery in their textiles, the weavers of Southern Appalachia continued to weave for at least another hundred years using single strand, hand spun, irregular wool yarn that was dyed with vegetable matter, by choice.

And, due to the nature of design, overshot can be woven on simpler four harness looms. This was a means for many weavers to explore this technique who may not have the financial means to a more complicated loom. With this type of patterning a blanket could be woven in narrower strips and then hand sewn together to cover larger beds. This allowed weavers to create complex patterns that spanned the entirety of the bed.

What makes overshot so incredibly interesting that it was fundamentally a development of American weavers looking to express themselves. Many of the traditional patterns have mysterious names such as “Maltese Cross”, “Liley of the West”, “Blooming Leaf of Mexico” and “Lee’s Surrender”. Although the names are curious, the patterns that were developed from the variations of four simple blocks are incredibly intricate and luxurious.

This is only the tip of the iceberg with regard to the history of this woven structure. If you are interested in learning more about the culture and meaning of overshot, check out these resources!

The National Museum of the American Coverlet- a museum located in Bedford, Pennsylvania that has an extensive collection of traditional and jacquard overshot coverlets. Great information online and they have a “Coverlet College” which is a weekend series of lectures to learn everything about the American coverlet. Check out their website - coverletmuseum.org

Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women – This was an exhibit that traveled from Lowell, Massachusetts, Morehead, Kentucky, Knoxville, Tennessee, Raleigh, North Carolina, and ended at the Royal Museum in Edinburgh, Scotland. The exhibit contained a large number of overshot coverlets and the personal histories of those who wove them. I learned of this exhibit through an article written by Kathryn Liebowitz for the 2001, June/July edition of the magazine “Art New England”. The book that accompanied the exhibit, written by Kathleen Curtis Wilson, contains some of the rich history of these weavers and the cloth they created. I have not personally read the book, but it is now on the top of my wish list, so when I do, you will be the first to know about it! The book is called Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women and I look forward to reading it.

One of my favorite parts of working on my Ancient Rose Scarf for the March/April 2019 issue of Handwoven was taking the time to research overshot and how it fits into the history of American weaving. As a former historian, I enjoyed diving into old classics by Lou Tate, Eliza Calvert Hall, and Mary Meigs Atwater, as well as one of my new favorite books, _Ozark Coverlets, by Marty Benson and Laura Lyon Redford Here’s what I wrote in the issue about my design:_

“The Earliest weaving appears to have been limited to the capacity of the simple four-harness loom. Several weaves are possible on this loom, but the one that admits of the widest variations is the so-called ‘four harness overshot weave,’—and this is the foremost of the colonial weaves.” So wrote Mary Meigs Atwater in The Shuttle-Craft Book of American Hand-Weaving when speaking of the American coverlet and the draft s most loved by those early weavers.

Overshot, in my mind, is the most North American of yarn structures. Yes, I know that overshot is woven beyond the borders of North America, but American and Canadian weavers of old took this structure and ran with it. The coverlets woven by weavers north and south provided those individuals with a creative outlet. Coverlets needed to be functional and, ideally, look nice. With (usually) just four shaft s at their disposal, weavers gravitated toward overshot with its stars, roses, and other eye-catching patterns. Using drafts brought to North America from Scotland and Scandinavia, these early weavers devised nearly endless variations and drafts, giving them delightful names and ultimately making them their own.

When I first began designing my overshot scarf, I used the yarn color for inspiration and searched for a draft reminiscent of poppies. I found just what I was looking for in the Ancient Rose pattern in A Handweaver’s Pattern Book. When I look at the pattern, I see poppies; when Marguerite Porter Davison and other weavers looked at it, they saw roses. I found out later that the circular patterns—what looked so much to me like flowers—are also known as chariot wheels.

I never really thought of using different colors for overshot before, but after feeling inspired by a group discussion, I decided to try it! I like it a lot and will probably do it again. The warp is pink, yellow, and blue. The tabby weft is the same rotation of pink, yellow, and blue, while…

As I began to plan the structure of the piece I knew that using an overshot technique for my weaving would probably give me the visual texture that I desired.

The overshot technique in weaving is accomplished by using two different thickness ofthread alternated in the weaving rows. The pattern row is made using the thicker of the two threads and usually skips over several threads to achieve the desired pattern that you are weaving. The thinner of the two threads is woven across the warp before and after each thicker pattern thread to “lock in” the pattern thread. The thinner threads are woven in tabby (weaving speak for plain weave).

I feel that using the overshot weaving technique helped me to capture the textual feeling I wanted for this runner. Here is how the project progressed and a list of the yarns that were used.

With the color pallet and types of yarn I chose and using the overshot technique, I felt like I was able to achieve the look that I wanted for this project. What do you think??

Half way through my weaving I decided I wanted to add a little something special to the piece that would bring the cultural influence in the tribal shield that inspired me to create this project to begin with. As I searched for that special something, I found a vendor on Etsy that imported fair trade beads from Africa. Handmade metal and hand-carved bone beads. I was pretty excited! Special handmade beads from another artist to compliment a handmade runner, just what the runner needed forthat finishing touch. When the beads arrived I laid them out on the runner that I was almost finished weaving and knew it was definitely the perfect accent!

Adding the beads to the finished runner was a long and tedious task but definitely worth the work, time and effort when I saw the finished project!! Once the beading was finished all that was left was to do the finishing wash and block drying and trimming off any overlapped threads in the weaving.

I actually had some beautiful brass and bone beads leftover from my weaving projects so I made those into some fun jewelry pieces . I’ll have some pictures of those in my next blog post.

The Big Book of Weaving – Handweaving in the Swedish Tradition: Techniques, Patterns, Designs and Materials by Laila Lundell has been my reading selection for the past few weeks. There are books that you speed through and they give you great ideas. This is a book that is perfectly suited for winter months when you can take time to digest a section before moving on to the next.

This book has often been used as a textbook for new weavers wanting to know how to get started with their first floor loom. The project sequence starts from the very beginning using plain weave and moves through pattern weaving. The author presents both 4 and 8 shaft projects for each type of weaving.

Projects that I found quite interesting – “Kitchen Towels with Small Blocks” that can be woven with 16/2 cotton. In this project Ms. Lundell also offers a complete project plan for weaving the bands needed for hanging towels. A great mystery solved!

“Choosing the right materials for a weaving takes a lot of knowledge. It’s a good idea to train your eyes and fingertips to become familiar with various materials and to learn about their special qualities”

As weavers it’s not uncommon to come across weaving drafts that are decades or even centuries old. In her article for the November/December 2017 issue of Handwoven, Madelyn van der Hoogt teaches you how to decipher old overshot drafts. Check out the issue to discover more vintage drafts and projects inspired by famous weavers. ~Christina

Overshot is a miracle of design potential on only four shafts. Somewhere, sometime long ago, a weaver looked at 2/2 twill and said: What if I add a tabby weft and repeat each two-thread pair for longer floats? Incredible patterns evolved, shared by colonial weavers with each other on small pieces of precious paper. Luckily, many of these drafts were saved and have become part of our weaving literature. In some of the older sources, the drafting format looks very confusing. Here is a guide to using them.

In the days when paper was hard to come by and writing was done by dipping a quill in ink, drafting formats for weaving were as abbreviated as possible. Overshot patterns are so elaborate that they can’t be communicated by words or short repeats the way simple twills can (point, rosepath, straight, broken, etc.). Complete drafts are necessary. Threading repeats are often long—some with as many as 400 threads. A number of shorthand methods thereby evolved that are similar to our use of profile drafts for other block weaves. But the way overshot works doesn’t allow a strict substitution of threading units for blocks on a profile threading draft.

Overshot drafting formats: Figure 1 is from Davison’s A Handweaver’s Source Book, Figure 2 is from Weaver Rose, and Figure 3 is from Wilson and Kennedy’s Of Coverlets.

Figures 1–3 show the most common early drafting methods. (Compare their length with the thread-by-thread version in Figure 5.) In shorthand drafts, each overshot block contains an even number of threads, four per block in these. (Block labels in red are added to Figures 1, 2, and 3 for clarity.) In Figure 1, from Marguerite Davison’s A Handweaver’s Source Book, the numbers tell how many times to thread each block; the rows tell which block to thread (A = 1-2, B = 3-2, C = 3-4, and D = 1-4). Note how the blocks always start on an odd shaft to preserve the even/odd sequence across the warp. The first column of numbers on the right (2/2) means to thread Block A (shafts 1-2) two times, then thread Block B (shafts 3-2) two times, etc.

In Figure 2, the method used by Weaver Rose, the lines represent the shafts. The numbers represent the order in which to thread the shafts. Reading from the right: Thread shaft 1, 2, 1, 2 for Block A. Then, moving to Block B, thread 3, 2, 3, 2, etc. In Figure 3, from Of Coverlets, the pair of shafts for each block is given with the number of times to thread it. Reading from the right: Thread 1-2, 2x; 3-2, 2x; 3-4, 2x, 1-4, 2x, etc. Figure 4 shows the actual thread-by thread draft for Figures 1–3. It also shows the way this threading would appear in Keep Me Warm One Night. In the drafts in this book, each block is threaded with an even number of threads and circled.

However, in overshot, blocks share shafts. That is, Block A (on shafts 1-2) shares shaft 2 with Block B and shaft 1 with Block D. Block B shares shaft 2 with Block A and shaft 3 with Block C, etc. When, for example, Block B is woven, a pattern-weft float covers the four threads that have been threaded for Block B and the thread on shaft 2 in Block A and the thread on shaft 3 in Block C. The circled blocks in Figure 5 show the warp threads that will actually produce pattern in each block using the drafts in Figures 1–4. Notice that Block B on the right will show a weft float over six threads, but on the left over only four. The same imbalance occurs with Block C; see also the drawdown in Figure 8. In the drafts derived from these shorthand drafts, float lengths over blocks in symmetrical positions always differ from each other by two warp threads.

Unbalanced drafts can be balanced by removing (or adding) pairs of shafts from the circled blocks; see Figures 6–10. In fact, to reduce or enlarge any draft, first circle the blocks so that they overlap to include their shared threads as in Figure 5. Then add or subtract pairs of threads. Notice that Block D has an odd number of threads, which is true of all “turning” blocks. Turning blocks are blocks where threading direction changes (any shift from the ABCD direction to the DCBA direction or vice versa).

The overshot drafts in Marguerite Davison’s A Handweaver’s Pattern Book and in Mary Meigs Atwater’s The Shuttle-Craft Book of American Hand-Weaving have all been balanced; see their drafting formats in Figures 11 and 12.

The exhibition Politics at Home: Textiles as American History, in the Ruth Davis Design Gallery, features several woven coverlets from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; these domestic textiles helped establish the graphic language of American politics through both geometric and figured weaving patterns. These historical patterns continue to inspire the art and craft of weaving today. This online program will feature a brief virtual view of historical woven coverlets from the Helen Louise Allen Textile Collection and a conversation with Marianne Fairbanks, Assoc. Professor of Design Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Justin Squizzero, founder of The Burroughs Garret, whose own practices today respond in varied ways, with varied tools, to the artifacts and print sources of historical American weaving.

8613371530291

8613371530291