sett for overshot manufacturer

After returning from a fabulous time at the New England Weavers Seminar in July, I found myself rewriting the beginning of this article. I was so lucky to spend two days in a round-robin style class taught by Marjie Thompson entitled 18th & 19th Century High Fashion for the Middle Class. To say that Marjie knows an extraordinary amount about historic textiles seems to be an understatement. Oh, to have an hour swimming about in her brain!

There were ten of us in the class, and we rotated, weaving a new sample at each loom. Marjie shared her knowledge of the patterns we sampled, and I came away with an even greater interest in this subject in addition to a binder filled with samples. There really is no greater way to learn than a hands-on workshop. I am already preparing to wind a warp for a dimity project. I’ll keep you posted on my progress.

One interesting piece of information I learned is that overshot is a fairly modern term. Originally this type of weaving would have been referred to as floats or floatwork. It seems that many people are returning to this original terminology, though the weaving world has thus far shown little interest in making the change back. Personally, I like it. Floatwork sounds a bit less frenetic than overshot – as though I’m peacefully hitting my mark rather than missing it in a wild fashion.

Until recently, my floatwork experience was limited to one project. This was created using Cascade 220 back in April 2008. The pattern is Leaves on p. 118 of The Handweaver’s Pattern Directory by Anne Dixon. I was criticized for having floats that were too long and would easily snag, but I loved my fabric. I turned it into a little tote that fit perfectly into my bike basket and never experienced a snag. Thankfully I took a photo back then, as the bag is currently in storage and missing the bike paths of Boulder.

When I first considered writing this article, I wasn’t confident enough with my weaving vocabulary to write something that a true beginner might actually understand. The information out there assumed, and still assumes, a certain level of weaving knowledge. I learn best by seeing something demonstrated, not by trying to translate written instructions. So how does one write an article for people like me? Let’s start with some basic terminology.

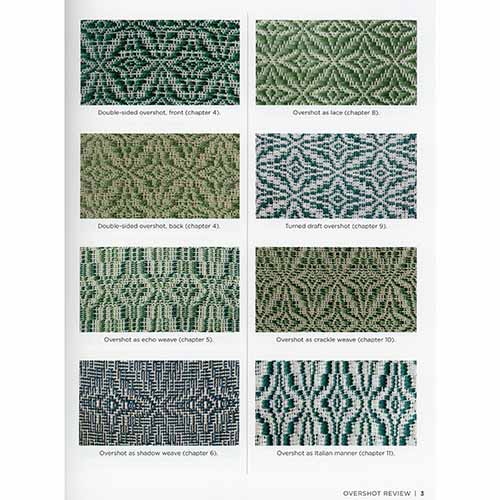

Floatwork, formerly known as overshot which was originally known as floatwork, is a block design traditionally woven on four shafts where a heavier pattern yarn floats above a plain weave ground cloth and creates a raised pattern. Your plain weave background cloth is woven using a finer yarn in your warp and in every other weft pick (these weft picks being the ‘use tabby’ part of your pattern.)

This finer yarn is hidden in places by the thicker yarn floats, blended in places with the thicker yarn (as plain weave) creating areas that are shaded (referred to as halftone), and woven across itself to create delicate areas of plain weave. Most of us think of antique coverlets when we hear ‘overshot.’

For some reason the term tabby has always annoyed me. It made me think of cats (I’ve got two – one of whom decided to take my seat when I got up to get a quick snack – and I love them both dearly) not weaving until I looked up the origin of the word on etymonline.com.

Initially, the concept of a block was the toughest one for me to grasp because I was looking at the pattern as a complete unit rather than a combination of units. The block is simply a unit or part of a particular pattern in the shape of a rectangle or a square. There are usually at least four threads in a block, two pattern and two tabby. So you treadle the same pattern pick two or more times in sequence (alternating with your anchoring tabby picks) to create a solid shape in your pattern. Think about coloring in graph paper. If you color in four squares in a row, it just looks like a thick line, right?

Here is the thing about floatwork that really helped it to make sense for me. It is basically a twill weave. As Mary Black puts it, “An examination of an overshot draft shows it to be made up of a repetitive sequence of the 1 and 2, 2 and 3, 3 and 4, and 4 and 1 twill blocks”.

Choosing yarns to weave floatwork can be challenging. Generally speaking you want your pattern yarn to be about twice the diameter, or grist, of your tabby/warp yarn. Your tabby yarn and your warp yarn are generally the same yarn. I say generally because I can see so many non-traditional ways to weave floatwork that involve breaking the rules. Imagine, for example, taking a small part of a given pattern and blowing it up to a massive scale to do a wall hanging or using three different yarns to create a completely different visual experience!

When treadling a block pattern with tabby picks, I find it helpful to tie my tabby treadles on one side and my pattern treadles on the other. This way you can dance back and forth from left to right as the treadling sequence is always going to be pattern-tabby-pattern-tabby. It feels more like walking or pedaling a bicycle to alternate in this manner.

I used a pattern from Mary Meigs Atwater’s Shuttle-Craft book listed in the Resources section. The draft is No. 18 Name Unknown and is on various pages depending on which printing of the book you have. (See the Resources section on the next page for an image of the draft.)

You can find it listed in the chapter or sub-chapter entitled ‘Notes on the Overshot Drafts.’ As someone who generally cheers on the underdog, I was drawn to this pattern without a name.

Atwater’s patterns are written for a sinking shed loom. For a rising shed loom, like the Baby Wolf I used, simply tie up the shafts left blank in the draft instead of the shafts she tells you to tie up. For all of her traditional floatwork patterns, including the pattern I used, this tie-up would be 3-4, 1-4, 1-2, 2-3. Your tabby tie up should be 1-3 and 2-4.

I washed this in my front-loading washing machine on the wool setting and air-dried it on the clothesline. There was a note in the book that No. 18 Name Unknown, and its friend No. 17, are “plain patterns and suitable for couch covers or the coverlet for a man’s room, rather than for more frivolous purposes”. Perfect. I’m not much for frivolous, and I had been looking for the perfect fabric to re-cover an old chair.

Here is a list of books and magazines that might be of interest if you’d like to learn more about floatwork/overshot. Many of these references include patterns in addition to thorough instructions.

Atwater, Mary Meigs. The Shuttle-Craft Book of American Handweaving. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1928. Just scored a first edition on ebay for $9! I now have three copies and am seriously in love with this book (taken with a grain of salt as she is rather traditional.)

If you can find this issue anywhere, I’d recommend picking it up. It’s full of great information on historic weaving, but also has a super article on understanding and writing drafts by Debbie Redding (aka Deborah Chandler).

If you have a particular interest in old coverlets, Eliza Calvert Hall’s A Book of Hand-Woven Coverlets and The Coverlet Book by Helene Bress are both interesting resources, the later being particularly thorough. I can only imagine the time and research that went into this pair of tomes. And if you are simply looking for patterns, The Handweaver’s Pattern Book by Marguerite Porter Davison and The Handweaver’s Pattern Directory by Anne Dixon are just for you.

As a young child visiting my great aunt in the nursing home, I would love to sneak to the lower floor and watch as residents wove blankets on large floor looms. I dreamt of weaving my own blanket. When I married and moved to Charlottesville, Virginia, over 30 years ago, I walked by a shop selling Schacht looms and offering classes. I went home with a table loom that day—a far cry from those big looms in the nursing home, but just as exciting. Money was tight, so I got an old spinning wheel and ordered raw fleeces to make my own yarn. When we moved to a small colony farm in Palmer, Alaska, in 1989, I knew right away I would get the perfect sheep to grow the best wool for my projects. Many more looms and sheep followed. Superfine merino sheep originally from Morehouse Farm in New York entered the picture in 1990 and our flock continued to grow and produce amazing wool. I was unable to keep up with the spinning and started sending our wool to Blackberry Ridge Woolen Mill, who do a great job spinning yarn. I use this yarn to make woolen goods for purchase, including blankets, shawls, scarves, and felted yardage.

When the original creamery of the farm became available, we thought it was a great opportunity to open a small weaving shop. Among the offerings are pre-warped merino wool projects, group scarf classes for those with little to no experience, private beginning warping classes, workshops, and studio time. Supplies are also available: yarn, finished products, looms, and all the other tools and equipment needed for weaving. We teach our group classes on Wolf Pup, Baby Wolf, and Mighty Wolf looms. It is convenient that we can move the looms as needed.

I have always dreamed of weaving a coverlet with my merino wool. I have a copy of Of Coverlets and have envisaged weaving every last one of them. I had eyed the Cranbrook for years and schemed a plan of how to acquire just one more loom. The shop had a great space that called its name. I wanted to weave on this beautiful loom, as well as have it available for others who share the same dream.

We purchased the 60″ 8-shaft Cranbrook with 12 treadles, the sliding threading bench, the sectional warping beam, tension box, and spool rack. The instructions were amazing, and it was easy to set up. The tension box was essential during the beaming process. We only had one Schacht spool rack which only controlled 20 of our 40 cotton bobbins. We improvised “racks” for the remaining 20 bobbins, which we do not recommend. The threading bench is another accessory that helped us to complete the warping of this large project (getting a friend to sit there is also recommended). With the ease of the tension box, it made sense to warp a 30-yard warp. In this way, the warped loom would be available for commissions and studio hours for those weavers who wish to weave their own coverlet.

One thing I did not realize when I bought the Cranbrook was that the treadles can lock into place to keep the shed open. This is especially helpful when weaving a wide project, as you don’t need to keep your foot on the treadle when you “catch” the shuttle at the other side. (If I had known this, I would have bought the 72″). I tied my tabby threads to treadles 3 and 4, skipped two treadles, and tied my pattern threads to treadles 7, 8, 9, and 10. It was easy to get in a great rhythm and “dance” through the pattern. Good music kept up my beat. The weighted hanging beater option made it relaxing and gave me a dense consistent beat with minimal effort.

Thread following Lee’s Surrender draft in A Handweaver’s Pattern Book, page 184. Repeat center block 30 times. Tie up according to draft. Note: the drafts in this book are written for a sinking shed loom. For a rising shed loom, tie up the blank boxes, not the boxes marked with X.

To remove the fabric from the loom, cut groups of 20 warp threads at least 12″ long and tie an overhand knot close to edge. I find it easier to do a few groups on one side, then the other, working my way towards the center. (See “Assembly” to continue the fringe pattern.) Remove the fabric from the front apron rod, untying the warp bundles to use for fringe.

For the second row of knots, divide each of these groups into two groups of 10. Skip the first group of 10. Combine the second and third groups of 10, tying them together in an overhand knot. Repeat across the weaving until you come to the last group of 10, which is left untied on this row.

For the final row of knots, divide each group of 20 into two groups of 10. Combine the first group of 10 (skipped on the previous row) and the second group of 10, tying them together in an overhand knot. Repeat with the third and fourth groups of 10, working across the weaving. There are no groups of 10 untied on this row.

If you are like us, your dining room table doesn"t get a lot of use for dining. That doesn"t mean it shouldn"t look great when it"s not being used! This elegant overshot runner can show off your table but also do equally fine duty as a dresser scarf or accent anywhere you need a little color and pattern. The 8/2 Cottolin is sett at 20 epi in the warp and is also the tabby weft. The 100% wool Highland is the pattern weft. For the majority of the weaving, you will alternate picks of these two yarns, which creates a firm background fabric of cottolin with a three-dimensional pattern of Highland that decorates the surface. We made a point of picking two colors that were similar to each other to emphasize the difference in texture. The kit makes one table runner with finished dimensions of 19" x 44" plus fringe. It can be hand washed and air dried, with a brief tumble in the dryer to fluff the fabric.

Over 50 instructional videos that guide you through making a warp, dressing your loom, weaving, finishing your cloth, and troubleshooting. View product images for course outline.

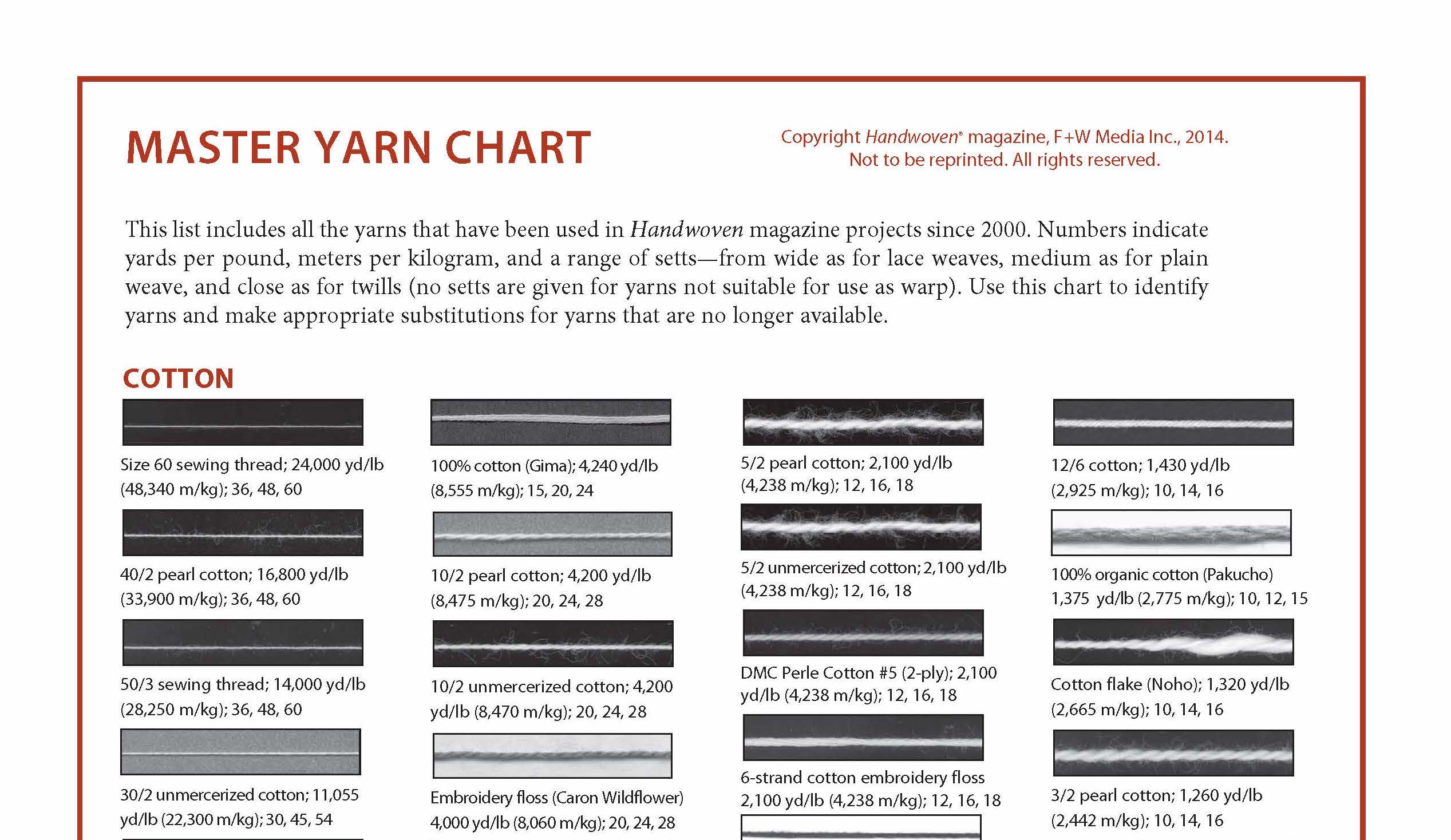

I was recently weaving an overshot pattern that used 10/2 cotton for the warp/ground weft and 5/2 cotton for the pattern weft. I also have a few cones of 3/2 cotton, but I didn’t know if they’d be too big compared with the 10/2. I have a large collection of 8/2 yarn as well, would the 5/2 yarn be better suited as a pattern weft for a project that uses 8/2 for the warp/ground instead? Are there any guidelines about what size yarns work best as the pattern weft for overshot versus the warp/ground weft?

Too many variables (the yarns, the specific overshot draft, and the desired hand of the fabric) are involved to give a single rule of thumb for pattern-weft size vs ground warp and weft size in overshot. Probably the most common yarns/setts for contemporary overshot fabrics are 10/2 cotton for warp and tabby weft at 24 epi and either 5/2 pearl cotton or 3/2 pearl cotton for the pattern weft. The fabrics woven with these yarns/setts are usually sturdy fabrics in a weight suitable for placemats and towels. 3/2 pearl cotton would also work (and not be too heavy) for the draft you’re using with 5/2 cotton, unless the pattern-weft floats are very short (this would be for a delicate design, usually looking very twill-like). In that case, the 3/2 pearl cotton weft would not pack in well enough and you’d see streaks of the tabby weft between pattern picks. By the same token, if your overshot design has long pattern-weft floats with large blocks of pattern, a 5/2 pearl cotton pattern weft is likely to be too thin to cover the blocks; in that case, you’d also see streaks of the tabby weft between pattern picks.

Wool pattern wefts have the capacity to full to cover the blocks with wet-finishing, so their size can vary depending on the nature of the wool. With 10/2 pearl cotton warp and tabby weft, I like using Harrisville Shetland (its heathered colors add to the effectiveness of an overshot design) or other 8/2 wools. These fabrics (cotton ground cloth, wool pattern weft) are also usually sturdy, with a hand similar to colonial coverlets. If a soft fabric is desired, as for a shawl or scarf, wool, wool/silk, or silk would be good choices for warp and tabby weft. For a soft overshot fabric in all wool, the sett should be as for plain weave, but open enough that the wool threads have room to swell with fulling. For a wool pattern weft to show well on a wool ground cloth, it should be two to three times as heavy as the ground warp and weft. I’d follow that principle for silk, too: Sett the warp as for plain weave and choose a weft two to three times as heavy as the the ground yarns.

8/2 cotton is usually sett at 20 ends per inch for plain weave. 3/2 pearl cotton would be a good size for the patten weft, but it is mercerized whereas the 8/2 cotton is not. The contrast between the sheen of the pearl cotton and the matte finish of the 8/2 cotton might work well, or might not. You’d have to sample to see. Another option is to use the 8/2 cotton doubled for a pattern weft.

People generally learn to weave with plain weave. To start the project we need to explain the sett. We wrap the yarn around a ruler, count the threads in one inch, and explain that we call the measurement the yarn size or grist or diameter (d) in wraps per inch (wpi) and that we will use half that number for our sett in ends per inch (epi) because our finished product will have half warp and half weft; then we hand the rulers to the students and let them try, admonishing not to overlap the threads and not to leave empty space in between them, as show below.

As the old saying does, “you gotta start somewhere”. We may mention that we will explain for future projects how the sett varies, but first impressions are powerful.

So, there was the time we used a 5/2 cotton sett at 16 epi – and 16 epi became “the sett” – for everything (“you told me to sett it at 16”); or the time that we used 3/2 cotton sett at 12 epi in a 12 dent reed and the conclusion was that the reed determines the sett, and not the other way around.

Those are rare instances, no doubt, but I do think that beginning weavers sometimes are looking for a magic number. “What’s the sett for 10/2 cotton?” asks the e-mail. Ah, if only sett were that simple! But with a bit of thought and understanding, it doesn’t have to be that hard, especially since we have some leeway.

For twills, a rule of thumb is that balanced twills should be sett at least 20% closer than plain weave. For that 5/2 yarn that we sett at 16 epi for plain weave, we would use 20 epi for a twill.

Unit weaves form lacey blocks and plain weave. You may read that lacey weaves should be sett more openly, the same or closer than plain weave. All of those are true and the sett varies on the proportions of these. If there is a lot of plain weave, we may want to use a more open sett to accentuate the lacey areas; if there are a lot of lacey blocks, then the sett should be a bit closer because the floats can make the fabric unstable. A huck lace that has all lace and no plain weave (except the selvages) using 10/2 Tencel® usually sett at 24 epi for plain weave, I may sett it at 26 epi.

Supplementary weaves have a ground of tabby, but the supplementary weft is generally larger than the ground weft, which is traditionally the same as the warp. In this case, I open up the tabby setta bit, to allow room for the supplementary weft. A 10/2 cotton, that may be sett at 24 epi for tabby, I sett at 18 epi for a tabby of a supplementary weave.

There is actually a formula for calculating the sett for different structures, but while I used to really like to use it, with time I found it unreliable for some unbalanced structures, and those that have different size floats with different picks, for example a birds’ eye twill.

Fortunately, we don’t have to do any calculations from the formula to find reasonable setts. While there are lots of sample setts on the web for the various commonly used yarns, there are differences in twist in yarns which effect the sett. The best place to find the sett for a specific yarn is to use the web site of the yarn vendor.

Manufacturers of yarns may provide either a range for setts or ranges for plain weave and twills. For example, for 10/2 cotton, the sett suggested may range from 18 to 36 epi. The 18 is for drapeable plain weave or a lacey structure with lots of plain weave, for example used in a scarf; the 36 is for unbalanced twills. About in the middle is a balanced twill, 24 epi.

Alternatively, the sett suggestions may say: plain weave: 18 - 24; twill 24 - 36; in this case, the 24 is suggested both for a sturdy plain weave, for example to be used in a placemat, or a balanced twill. The suggested setts for a given yarn usually take into consideration the fiber, so they are worth noting, even when wrapping the yarn to determine its grist.

If the weft is larger than the warp, the settmust be more open to make room for the weft; if the weft is smallerthan the warp, the settmust be closerto avoid the weft to pack in and make the cloth too stiff.

For example, for 10/2 cotton woven in plain weave for warp and weft, the average sett is 24 epi. For the runner below, woven with a larger ribbon, the warp was sett more openly at 18 epi.

The scarf below was woven with a multicolor 5/2 bamboo for warp and a purple 10/2 bamboo for weft in a twill. For a balanced twill, the sett of the 5/2 warp would have been 20 epi, but because the weft is smaller, a sett of 24 epi was used. This makes the fabric more stable but also allows the multicolor warp to be the focus of the scarf while still having good drape.

In an unbalanced fabric, the weft shows more on one side, the warp on the other as shown in the picture below of a 3/1 twill, front and back; 3/1 means that for every shot, 3 threads remain down while 1 thread is lifted.

How do we sett the warp for these fabrics? Closer than for a balanced twill. I already mentioned that when vendors give a range for twills, the upper value is for unbalanced fabrics. Let’s use the example of 5/2; we may sett it at 16 for plain weave, 18 for a balanced twill, and 22 epi for the 3/1 twill.

The general sett recommendations for 10/2 unmercerized cotton, 10/2 mercerized cotton and 10/2 Tencel®(which follows the cotton count) are the same. But there are differences. Look at the photo below:

There are 6 wraps for each of the three yarns, which are: 10/2 unmercerized cotton (blue), 10/2 Tencel®(rust) and 10/2 mercerized cotton (yellow), occupying the portion of an inch as labeled. Translated to epi, the setts would be 19, 20 and 23, respectively, with some differences, especially between the unmercerized and mercerized cotton; visually, I can see that the yellow yarn has a higher twist than the others. This is not surprising as I have found differences between mercerized cottons of the same count and Tencel®of the same count. In using the yarn, such differences may not matter, but I still think it is important to consult the yarn vendors for their sett recommendations.

I wouldn’t use 3/2 cotton to make a scarf, the fabric wouldn’t drape as well as I’d like, but 3/2 makes great mats; for a scarf, I would use 10/2 cotton, which I wouldn’t use for a table mat, I think the sturdier 3/2 works better.

In between is 5/2; it could be used for a scarf and for a matt – but not with the same sett. For a scarf I may use an open 18 epi, for a matt a tighter 20 epi.

The ranges given to us by manufacturers are rather close, but we have a lot more leeway. To weave a tapestry or a weft-faced rug, we sett the yarn 5 or 8 epi, depending on the size of the weft, so we can cover the warp totally, on both sides of the fabric, as shown in the photo below, front and back.

At the other end of the spectrum, we can weave a rug with rep weave, warp-faced plain weave; we sett rep close to 4 times the yarn wraps per inch, to make sure that the top and bottom of the fabric are both solid warp, as show in the photo below, front and back.

Which combinations you prefer may impact your fabric; if you like to beat hard, you make great rugs – what if you want to weave a scarf? You can adjust the sett.

Rather than fighting my tendencies, I adjust the sett. By using a slightly larger ends per inch than recommended, my warp will provide some resistance to the beating; and since a tight warp also promotes heavy beating, the closer sett helps with this tendency as well.

You see why I couldn’t answer that email “What’s the sett for 10/2 cotton?” with a single number, but here is a plan to get started. And, no, I won’t use the dirty 6-letter word (sample), although sometimes that’s the best way to get the answer.

Think about adjustments for the pattern, the weft size if different than the warp and what your finished product is going to be; adjust the starting epi accordingly; sometimes your adjustment may be a calculation (20% increase for twills), sometimes it’s “a little bit” higher or lower – 18 or 14 instead of 16, don’t use odd setts; if your calculations give you 21 epi, use 20 or 22, depending on what you are making.

Depending on the adjustment, there could be a potential tension problem because the threads no longer will travel a straight line from the back of the loom to the front, they will either fan out or squeeze in, depending on the direction of the new sett.

Once you are done, keep notes. This is the most important part for future use. Keep a spreadsheet if you are comfortable with them, or a table of some sort. List the following:

Your impressions: note whether you are totally happy with this sett, or whether you are relatively happy but next time you may sett this yarn more closely or further apart. And, yes, do this even if the project turned out not to be to your liking. That may be the best lesson.

When reading a published project, note the same information as above, even if you don’t plan on using it. Add it to your table or make a parallel table of use by other weavers. You can compare your setts with those of others and make conclusions about similarities and differences.

Soon you will have a table – your table – which will give you a feel for how you like to sett various yarns. Experience comes from paying attention to what we do right – and what we do not so right.

This project was really popular when I posted it on Instagram, so I thought I would share it here also. It is a simple overshot pattern - with a twist. Also a great way to show off some special yarn. The yarn I used for my pattern was a skein of hand spun camel/silk blend. I wove the fabric on my Jack loom but you could also use your four or eight shaft loom.

Overshot is a weave structure where the weft threads jump over several warp threads at once, a supplementary weft creating patterns over a plain weave base. Overshot gained popularity in the turn of the 19th century (although its origins are a few hundred years earlier than that!). Coverlets (bed covers) were woven in Overshot with a cotton (or linen) plain weave base and a wool supplementary weft for the pattern. The plain weave base gave structure and durability and the woollen pattern thread gave warmth and colour/design. Designs were basic geometric designs that were handed down in families and as it was woven on a four shaft loom the Overshot patterns were accessible to many. In theory if you removed all the pattern threads form your Overshot you would have a structurally sound piece of plain weave fabric.

I was first drawn to Overshot many years ago when I saw what looked to me like "fragments" of Overshot in Sharon Aldermans "Mastering Weave Structures".

I have not included details of number of warp ends, sett and yarn requirements for my project - you can do your calculations based on the sett required for plain weave in the yarn you wish to use.

I wanted to use my handspun - but I only had a 100gms skein, I wanted to maximise the amount of fabric I could get using the 100gms. I thought about all the drafts I could use that would show off the weft and settled on overshot because this showcases the pattern yarn very nicely. I decided to weave it “fragmented” so I could make my handspun yarn go further. I chose a honeysuckle draft.

When doing the treadle tie-up I used 3 and 8 for my plain weave and started weaving from the left, treadle 3 - so you always know which treadle you are up to - shuttle on the left - treadle 3, shuttle on the right treadle 8. I then tied up the pattern on treadles 4,5,6 and 7. You can work in that order by repeating the sequence or you can mix it up and go from 4 to 7 and back to 4 again etc. You will easily see what the pattern is doing.

Many years ago, I finally got to try weaving. I took the Beginning to Weave workshop through the Ottawa guild. At that time, 1989, the OVWSG did not have a studio space to house what guild equipment we had acquired. (The Guild had an old second-hand 100 inch loom and 6 or 7 table looms. There may have been a floor loom too but I was distracted by the 100 inches of loom, so do not remember). All the looms lived in one of our guild members’ very big basements. On weekends, she either taught weaving workshops or hosted weavers working on the 100 inch loom. It sounded like a busy basement! I remember 4 weekends of driving to a little town just east of Ottawa. I took the table loom home each week to do homework. I still remember the sound of the mettle heddles rattling as I drove down the highway, back and forth to the classes. Then I think there were two more weekends of Intermediate weaving and Dona sent me off and I was weaving!

During the workshop, I found pickup seemed strangely familiar as my brain watched my fingers happily lifting and twisting threads for the various lace and decorative weave patterns. The other thing that my brain went “ooh this is cool!” was Overshot. It is a weave structure that requires a ground and a pattern thread, (two shuttles). One is fine like the warp and the pattern thread is thicker and usually wool. I was still reacting to wool so I used cotton for both. My original goal was to draft and weave a Viking textile for myself but I put that aside for a moment, I will get back to that later.

The first thing I wove after my instruction was a present for my Mom. she had requested fabric to make a vest. I looked through A Handweaver’s Pattern Bookby Marguerite Porter Davison and found an overshot pattern that I thought we both would like. I wove it in two shades of blue (Mom’s favourite colour), at a looser thread count than usual. (Originally the overshot weave structure was used to make coverlets, so were tightly woven and a bit stiff, while I liked the pattern I wanted the fabric to be much more drapey.) Even worse, I did not want it to be as hard-edged in the pattern as it was originally intended so I tried a slub cotton as a test and loved it.

So, for any sane weaver, it was all wrong! Wrong set, wrong fibre, wrong colour choices! It was fabulous and perfect. I kept the sample as a basket cover and at either the end of 1989 or the beginning of 1990, I gave Mom the yardage for her vest. “Oh this is too nice to cut” Mom Said, so it lived on the back of her favourite reading chair as a headrest until her most recent move (2015?) it never did get to be a vest but it has been well enjoyed.

In the Exhibition The Inkle band, hanging beside the overshot, I wove much more recently. I used an Inkle loom and a supplemental warp thread. This means weaving with an extra separate thread that was not part of the main warp on the loom. I used a yarn with a fuzzy caterpillar-like slub.

I was going to tell you about my original goal in learning to weave, the mysterious Fragment #10 from a Viking excavation from around the year 1000, but I have likely confused you with weaving enough for one day. So I will save that for another chat. (don’t forget the Inkle loom I would like to tell you a bit more about that in another post too. I promise I will get back to felting in the not-too-distant future)

I am currently weaving a tablecloth with a 10/2 cotton warp, a 20/2 cotton tabby weft, and a 6/2 cotton pattern weft. I’d like to do a series of scarves with the remainder of the warp using a finer silk for the pattern weft but I am curious about the effect it will have on the pattern, Lee’s Surrender. I am assuming the pattern will be squished down and distorted rather than the neat exact squares and curves in the current piece, but it may make for an interesting effect in a scarf.

Usually, overshot is woven with a warp and tabby weft of the same size and a pattern weft that is two to three times heavier/thicker than the warp and tabby weft. In your tablecloth, you used a finer tabby weft than the warp yarn. Sometimes this is done in order to make it easier to beat in the tabby and pattern wefts so that the pattern weft covers the pattern area without showing streaks of tabby weft. This might especially help when weaving a wide piece like a tablecloth or coverlet (it takes more force to achieve the same number of picks per inch in a wider piece than in a narrower piece).

If you were to use the same warp yarn for a scarf and make the pattern weft finer, the pattern weft would be unlikely to cover the blocks showing pattern—you would see streaks of tabby weft between pattern picks (your 6/2 cotton pattern weft is already fairly fine for a 10/2 cotton warp). I"m assuming you would be using only a section of the warp for a scarf, since a scarf would be narrower than a tablecloth. What you could do is tie on a finer warp to the section of 10/2 warp you want to use for the scarf, and after the warp is beamed, re-sley to a closer sett. Overshot can make a lovely structure for a scarf, but usually in finer yarns than 10/2 cotton. The scarf shown here is woven with a 30/2 silk warp (at 28 epi), a 30/2 silk tabby weft, and a 20/2 silk pattern weft. A 20/2 cotton warp, 20/2 cotton tabby weft, and 10/2 cotton pattern weft would also make a beautiful scarf weight. If you do use your 10/2 cotton warp, I"d stick with the 6/2 cotton pattern weft.

The second part of your question has to do with whether or not using a finer pattern weft would distort the pattern. With overshot, you can always adjust the appearance of a pattern block (its height) by adding or subtracting pattern picks. Most overshot motifs are designed to be symmetrical (as tall as they are wide). Always allow some extra warp for sampling until you can determine the number of pattern picks (alternating with tabby) required to achieve symmetrical motifs ("weaving to square").

Overshot: The earliest coverlets were woven using an overshot weave. There is a ground cloth of plain weave linen or cotton with a supplementary pattern weft, usually of dyed wool, added to create a geometric pattern based on simple combinations of blocks. The weaver creates the pattern by raising and lowering the pattern weft with treadles to create vibrant, reversible geometric patterns. Overshot coverlets could be woven domestically by men or women on simple four-shaft looms, and the craft persists to this day.

Summer-and-Winter: This structure is a type of overshot with strict rules about supplementary pattern weft float distances. The weft yarns float over no more than two warp yarns. This creates a denser fabric with a tighter weave. Summer-and-Winter is so named because one side of the coverlet features more wool than the other, thus giving the coverlet a summer side and a winter side. This structure may be an American invention. Its origins are somewhat mysterious, but it seems to have evolved out of a British weaving tradition.

Double Cloth: Usually associated with professional weavers, double cloth is formed from two plain weave fabrics that swap places with one another, interlocking the textile and creating the pattern. Coverlet weavers initially used German, geometric, block-weaving patterns to create decorative coverlets and ingrain carpeting. These coverlets contain twice the yarn and are twice as heavy as other coverlets.

Beiderwand: Weavers in Northern Germany and Southern Denmark first used this structure in the seventeenth century to weave bed curtains and textiles for clothing. Beiderwand is an integrated structure, and the design alternates sections of warp-faced and weft-faced plain weave. Beiderwand coverlets can be either true Beiderwand or the more common tied-Beiderwand. This structure is identifiable by the ribbed appearance of the textile created by the addition of a supplementary binding warp.

Multi-harness/Star and Diamond: This group of coverlets is characterized not by the structure but by the intricacy of patterning. Usually executed in overshot, Beiderwand, or geometric double cloth, these coverlets were made almost all made in Eastern Pennsylvania by professional weavers on looms with between twelve and twenty-six shafts.

America’s earliest coverlets were woven in New England, usually in overshot patterns and by women working collectively to produce textiles for their own homes and for sale locally. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book, Age of Homespun examines this pre-Revolutionary economy in which women shared labor, raw materials, and textile equipment to supplement family incomes. As the nineteenth century approached and textile mills emerged first in New England, new groups of European immigrant weavers would arrive in New England before moving westward to cheaper available land and spread industrialization to America’s rural interior.

The coverlets from New York and New Jersey are among the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlets. NMAH possesses the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlet (dated 1817), made on Long Island by an unknown weaver. These coverlets are associated primarily with Scottish and Scots-Irish immigrant weavers who were recruited from Britain to provide a skilled workforce for America’s earliest woolen textile mills, and then established their own businesses. New York and New Jersey coverlets are primarily blue and white, double cloth and feature refined Neoclassical and Victorian motifs. Long Island and the Finger Lakes region of New York as well as Bergen County, New Jersey were major centers of coverlet production.

Coverlet weavers were among some of the earliest European settler in the Northwest Territories. After helping to clear the land and establish agriculture, these weavers focused their attentions on establishing mills and weaving operations with local supplies, for local markets. This economic pattern helped introduce the American interior to an industrial economy. It also allowed the weaver to free himself and his family from traditional, less-favorable urban factory life. New land in Ohio and Indiana enticed weavers from the New York and Mid-Atlantic traditions to settle in the Northwest Territories. As a result, coverlets from this region hybridized, blending the fondness for color found in Pennsylvania coverlets with the refinement of design and Scottish influence of the New York coverlets.

Southern coverlets almost always tended to be woven in overshot patterns. Traditional hand-weaving also survived longest in the South. Southern Appalachian women were still weaving overshot coverlets at the turn of the twentieth century. These women and their coverlets helped in inspire a wave of Settlement Schools and mail-order cottage industries throughout the Southern Appalachian region, inspiring and contributing to Colonial Revival design and the Handicraft Revival. Before the Civil War, enslaved labor was often used in the production of Southern coverlets, both to grow and process the raw materials, and to transform those materials into a finished product.

Because so many coverlets have been passed down as family heirlooms, retaining documentation on their maker or users, they provide a visual catalog of America’s path toward and response to industrialization. Coverlet weavers have sometimes been categorized as artisan weavers fighting to keep a traditional craft alive. New research, however, is showing that many of these weavers were on the forefront of industry in rural America. Many coverlet weavers began their American odyssey as immigrants, recruited from European textile factories—along with their families—to help establish industrial mills in America. Families saved their money, bought cheaper land in America’s rural interior and took their mechanical skills and ideas about industrial organization into the American heartland. Once there, these weavers found options. They could operate as weaver-farmers, own a small workshop, partner with a local carding mill, or open their own small, regional factories. They were quick to embrace new weaving technologies, including power looms, and frequently advertised in local newspapers. Coverlet weavers created small pockets of residentiary industry that relied on a steady flow of European-trained immigrants. These small factories remained successful until after the Civil War when the railroads made mass-produced, industrial goods more readily available nationwide.

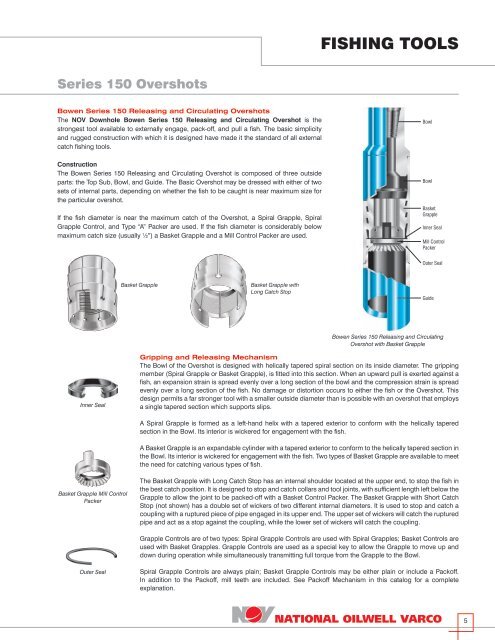

A wide variety of overshot fishing tools options are available to you, such as swivel, fishing plier and spool.You can also choose from ocean boat fishing, lake and river overshot fishing tools,

Amanda has been creating with fiber for almost twenty years. After taking numerous art classes in college including ceramics, intaglio printing, and wood carving, Amanda became a self-taught crocheter in 2003. She picked up the love of weaving and knitting over the last several years through classes at Alamitos Bay Yarn Company. Amanda has taught rigid heddle weaving with Carla since 2019.

I am attempting some upholstery fabric for the first time and decided on Brassard 8/2 cottolin for the warp and Harrisville Shetland for the weft. The structure is “Waldenweave” from Bertha Gray Hayes collection of miniature overshot…. I am developing a “thing” for overshot and really like all aspects of it.

8613371530291

8613371530291