permian power tong quotation

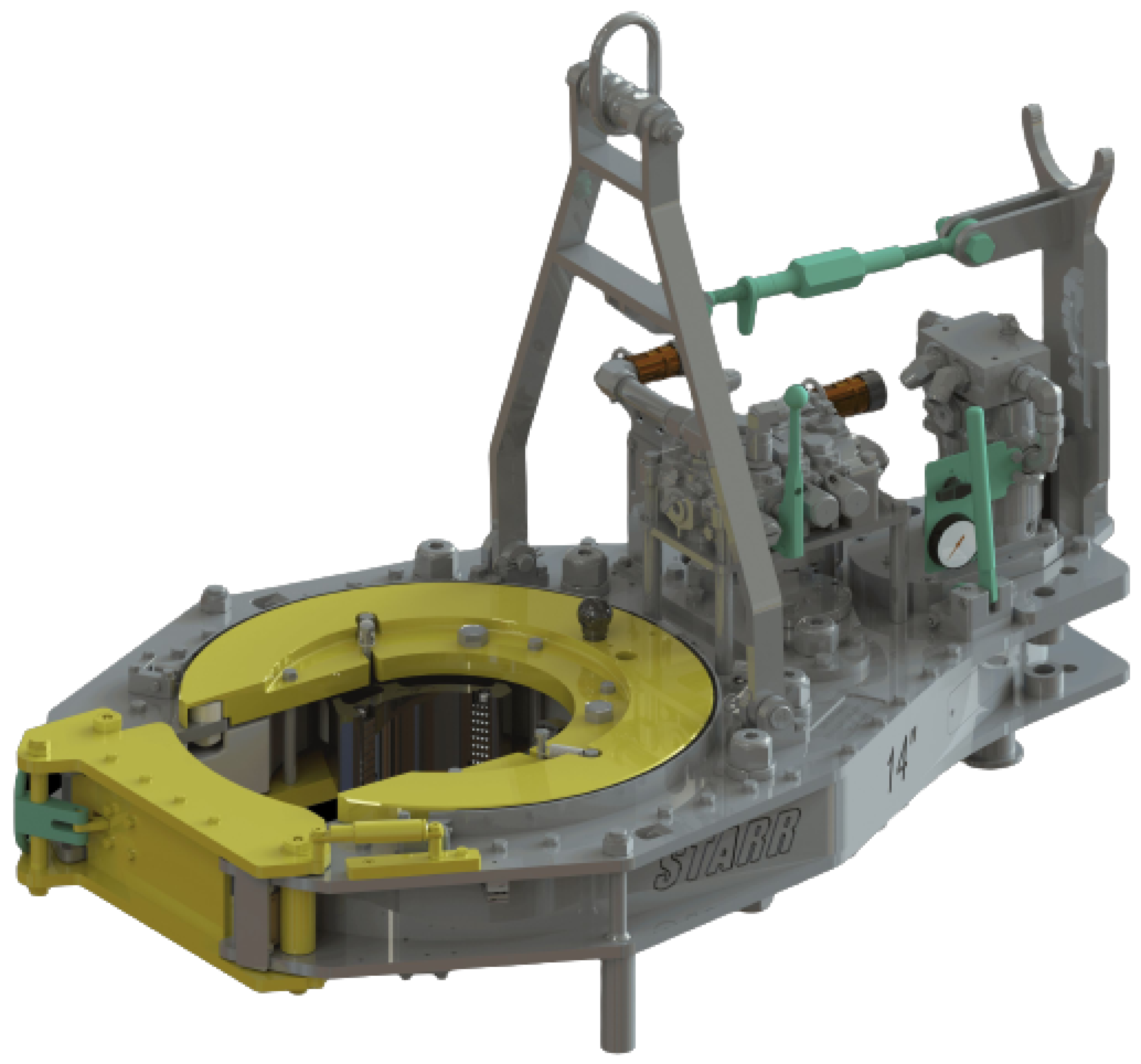

The 14-100 hydraulic power tong provides 100,000 ft-lb (135,600 N∙m) of torque capacity for running and pulling 7- to 14-in. casing. The tong has a unique gated rotary, a free-floating backup, and a hydraulic door interlock.

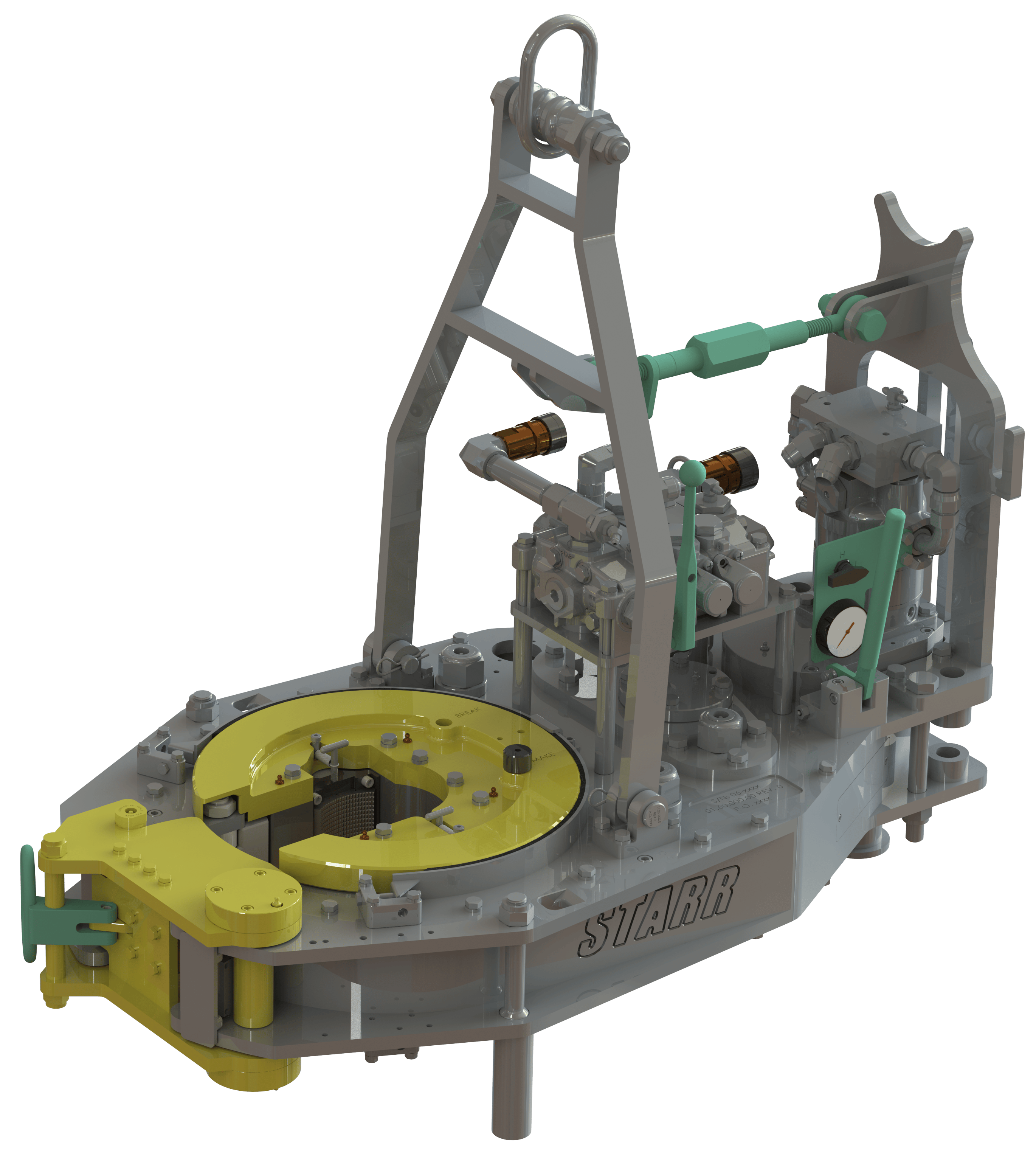

Our 14-50 high-torque casing tong provides 50,000 ft-lb (67,790 N∙m) of torque capacity for running and pulling 6 5/8- to 14-in. casing. The tong has a unique gated rotary, a free floating backup, and a hydraulic door interlock.

The 16-25 hydraulic casing tong provides 25,000 ft-lb (33,900 N∙m) of torque capacity for running and pulling 6 5/8- to 16-in. casing. The tong features a unique gated rotary and as many as seven contact points that create a positive grip without damaging the casing.

Rigged up without rig modifications, our 21-300 riser tong is the only tong capable of producing 300,000 ft-lb (406,746 N∙m) of continuous rotational torque in both makeup and breakout mode. The power it achieves in a compact size compares with a conventional 24-in. casing tong.

The 24-50 high-torque casing tong provides 50,000 ft-lb (67,790 N∙m) of torque capacity for running and pulling 10 3/4- to 24-in. casing. The tong features a unique gated rotary, a free-floating backup, and a hydraulic door interlock.

The 30-100 high-torque casing tong provides 100,000 ft-lb (135,600 N∙m) of torque capacity for running and pulling 16- to 30-in. casing. The tong features a unique gated rotary, a free-floating backup, and a hydraulic door interlock.

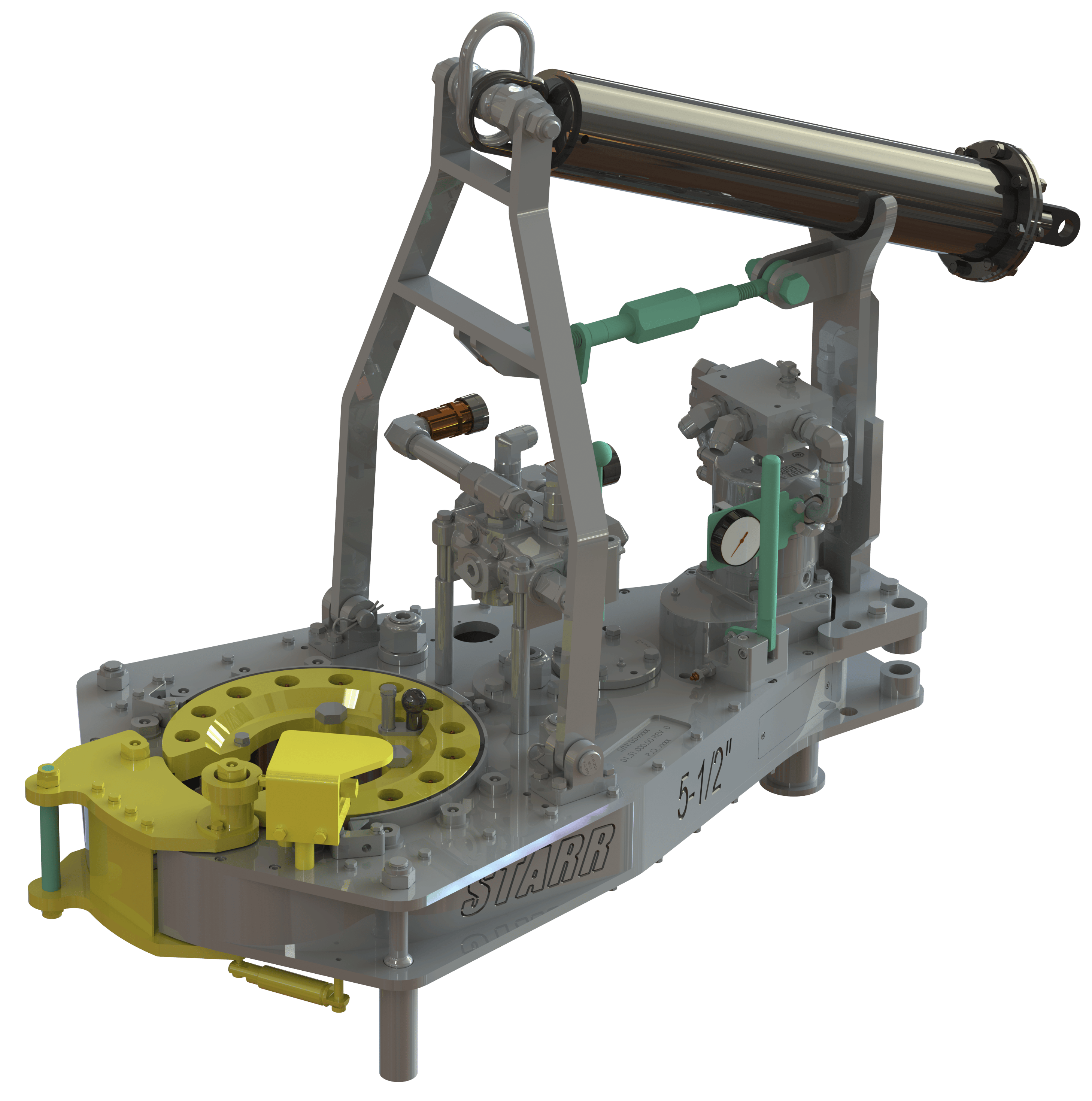

The 5.5-15 hydraulic tubing tong provides 15,000 ft-lb (20,340 N∙m) of torque capability for makeup and breakout of 1.66- to 5.5-in. tubing and premium or standard connections on corrosion‑resistant alloy tubulars. The tong features an ergonomic, lightweight design with a free-floating hydraulic backup.

The 7.6-30 hydraulic tubing tong provides 30,000 ft-lb (40,670 N∙m) of torque capability for makeup and breakout of 2 3/8- to 7 5/8-in. tubing and premium or standard connections on corrosion‑resistant alloy tubulars. The tong features an ergonomic, lightweight design with a free-floating hydraulic backup.

Our SpeedTork 8.0-70 tong provides torques up to 70,000 ft-lb (94,900 N∙m) and 360° rotation in makeup and breakout operations. It can torque drillpipe connections, drillstring components, drilling tools, packers, couplings, and valves.

A two-speed Hydra-Shift® motor coupled with a two-speed gear train provides (4) torque levels and (4) RPM speeds. Easily shift the hydraulic motor in low speed to high speed without stopping the tong or tublar rotation, saving rig time.

A patented door locking system (US Patent 6,279,426) for Eckel tongs that allows for latchless locking of the tong door. The tong door swings easily open and closed and locks when torque

is applied to the tong. When safety is important this locking mechanism combined with our safety door interlock provides unparalleled safety while speeding up the turn around time between connections. The Radial Door Lock is patented protected in the following countries: Canada, Germany, Norway, United Kingdom, and the United States.

The field proven Tri-Grip® Backup features a three head design that encompasses the tubular that applies an evenly distributed gripping force. The Tri-Grip®Backup provides exceptional gripping capabilities with either Eckel True Grit® dies or Pyramid Fine Tooth dies. The hydraulic backup is suspended at an adjustable level below the power tong by means of three hanger legs and allowing the backup to remain stationary while the power tong moves vertically to compensate for thread travel of the connection.

During the Three Kingdoms, the territory of present-day Yunnan, western Guizhou and southern Sichuan was collectively called Nanzhong. The dissolution of Chinese central authority led to increased autonomy for Yunnan and more power for the local tribal structures. In AD 225, the famed statesman Zhuge Liang led three columns into Yunnan to pacify the tribes. His seven captures of Meng Huo, a local magnate, is mythologized in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

By the 750s, Nanzhao had conquered Yunnan and became a potential rival to Tang China. The following period saw several conflicts between Tang China and Nanzhao. In 750, Nanzhao attacked and captured Yaozhou, the largest Tang settlement in Yunnan. In 751, Xianyu Zhongtong (鮮于仲通), the regional commander of Jiannan (present-day Sichuan), led a Tang campaign against Nanzhao. The king of Nanzhao, Geluofeng, regarded the previous incident as a personal affair and wrote to Xianyu to seek peace. However, Xianyu Zhongtong detained the Nanzhao envoys and turned down the appeal. Confronted with Tang armies, Nanzhao immediately turned its allegiance to the Tibetan Empire.

Nanzhao"s expansion lasted for several decades. In 829, Nanzhao suddenly plundered Sichuan and entered Chengdu. When it retreated, hundreds of Sichuan people, including skilled artisans, were taken to Yunnan. In 832, the Nanzhao army captured the capital of the Pyu kingdom in modern upper Burma. Nanzhao also attacked the Khmer peoples of Zhenla. Generally speaking, Nanzhao was then the most powerful kingdom in mainland Southeast Asia, and played an extremely active role in multistate interactions.

In 902, Zheng Maisi, the Qingpingguan (清平官,"Prime Minister") of Nanzhao, murdered the infant king of Nanzhao, and established a new kingdom called Dachanghe. Nanzhao, a once-powerful empire, disappeared. In 928, Yang Ganzhen (楊干貞) usurped the Dachanghe king and established Zhao Shanzheng, a qingpingguan as emperor of Datianxing (大天興). In 929, Yang Qianzhen abolished Zhao Shanzheng and established himself as Emperor of Dayining (大義寧).

Yunnan is at the far eastern edge of the Himalayan uplift, and was pushed up in the Pleistocene, primarily in the Middle Pleistocene, although the uplift continues into the present. The eastern part of the province is a limestone plateau with karst topography and unnavigable rivers flowing through deep mountain gorges. The main surface formations of the plateau are the Lower Permian Maokou Formation, characterized by thick limestone deposits, the Lower Permian Qixia Formation, characterised by dolomitic limestones and dolomites, the Upper Permian basalts of the Ermeishan Formation (formerly Omeishan plateau basalts), and the red sandstones, mudstones, siltstones, and conglomerates of the Mesozoic–Paleogene, including the Lufeng Formation and the Lunan Group (Lumeiyi, Xiaotun, and Caijiacong formations). In this area is the noted Stone Forest or Shilin, eroded vertical pinnacles of limestone (Maokou Formation). In the eastern part the rivers generally run eastwards. The western half is characterized by mountain ranges and rivers running north and south.

Yunnan has sufficient rainfall and many rivers and lakes. The annual water flow originating in the province is 200 cubic kilometres, three times that of the Yellow River. The rivers flowing into the province from outside add 160 cubic kilometres, which means there are more than ten thousand cubic metres of water for each person in the province. This is four times the average in the country. The rich water resources offer abundant hydro-energy. China is constructing a series of dams on the Mekong to develop it as a waterway and source of power; the first was completed at Manwan in 1993.

Yunnan is one of China"s relatively undeveloped provinces with more poverty-stricken counties than the other provinces. In 1994, about 7 million people lived below the poverty line of less than an annual average income of 300 yuan per capita. They were distributed in the province"s 73 counties mainly and financially supported by the central government. With an input of 3.15 billion yuan in 2002, the absolutely poor rural population in the province has been reduced from 4.05 million in 2000 to 2.86 million. The poverty alleviation plan includes five large projects aimed at improving infrastructure facilities. They involve planned attempts at soil improvement, water conservation, electric power, roads, and "green belt" building. Upon the completion of the projects, the province hopes this will alleviate the shortages of grain, water, electric power and roads.

Yunnan lags behind the east coast of China in relation to socio-economic development. However, because of its geographic location the province has comparative advantages in regional and border trade with Southeast Asian countries. The Lancang River (upper reaches of Mekong River) is the waterway to southeast Asia. In recent years land transportation has been improved to strengthen economic and trade co-operation among countries in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Yunnan"s abundance in resources determines that the province"s pillar industries are: agriculture, tobacco, mining, hydro-electric power, and tourism. In general, the province still depends on the natural resources. The secondary sector is currently the largest industrial tier in Yunnan, contributing more than 45 percent of GDP. The tertiary sector contributes 40 percent and agriculture 15 percent. Investment is the key driver of Yunnan"s economic growth, especially in construction.

Within the province, the Kunming–Yuxi, opened in 1993, and the Guangtong–Dali, opened in 1998, expanded the rail network to southern and western Yunnan, respectively. The Dali–Lijiang Railway, opened in 2010, brought rail service to northwestern Yunnan. That line is planned to be extended further north to Xamgyi"nyilha County.

Generally, rivers are obstacles to transport in Yunnan. Only very small parts of Yunnan"s river systems are navigable. However, China is constructing a series of dams on the Mekong to develop it as a waterway and source of power; the first was completed at Manwan in 1993.

Yunnan"s cultural life is one of remarkable diversity. Archaeological findings have unearthed sacred burial structures holding elegant bronzes in Jinning, south of Kunming. In northeastern Yunnan, frescoes of the Jin dynasty (266–420) have been discovered in the city of Zhatong. Many Chinese cultural relics have been discovered in later periods. The lineage of tribal way of life of the indigenous peoples persisted uninfluenced by modernity until the mid-20th century. Tribal traditions, such as Yi slaveholding and Wa headhunting, have since been abolished. After the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), in which several minority cultural and religious practices were suppressed, Yunnan has come to celebrate its cultural diversity and subsequently many local customs and festivals have flourished.

Dardess, John W. (2003). "Chapter 3: Did the Mongols Matter? Territory, Power, and the Intelligentsia in China from the Northern Song to the Early Ming" (PDF). In Smith, Paul Jakov; von Glahn, Richard (eds.). The Song –Yuan-Ming Transition in Chinese History. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. p. 111. ISBN 9780674010963. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-16. Retrieved 2016-07-11.

8613371530291

8613371530291