rongsheng fishers made in china

Hong Kong: As is common for Chinese firms that have suffered embarrassing financial setbacks, a famous name in shipbuilding is mulling a change in brand and focus. China Rongsheng Heavy Industries, the largest private shipbuilder in China, is considering changing its name to China Huarong Energy Company.

Rongsheng has been one of the highest profile casualties from the shipbuilding downturn. Earlier reports had suggested that the Hong Kong-listed entity would be restructured with state-run yard conglomerate CSSC coming in to help it out. [30/10/14]

HONG KONG, Nov 26 (Reuters) - China Rongsheng Heavy Industries Group, the country’s largest private shipbuilder, said its chairman had stepped down just three months after the company posted its sharpest fall in half-year net profit.

Listed in November 2010, Rongsheng was hit by an insider dealing scandal involving a firm owned by Zhang ahead of the $15.1 billion bid for Canadian oil firm Nexen Inc by China offshore oil and gas producer CNOOC.

Rongsheng said earlier this month that investment firm Well Advantage, controlled by Zhang, had agreed to pay $14 million as part of a settlement deal with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

In August, Rongsheng posted an 82 percent drop in half-year profit on a dearth of new orders and warned economic uncertainties would continue to weigh on the global shipping market.

As part of the changes at China Rongsheng, the company said that Zhang De Huang was retiring and had resigned as an executive director and as vice chairman of the board.

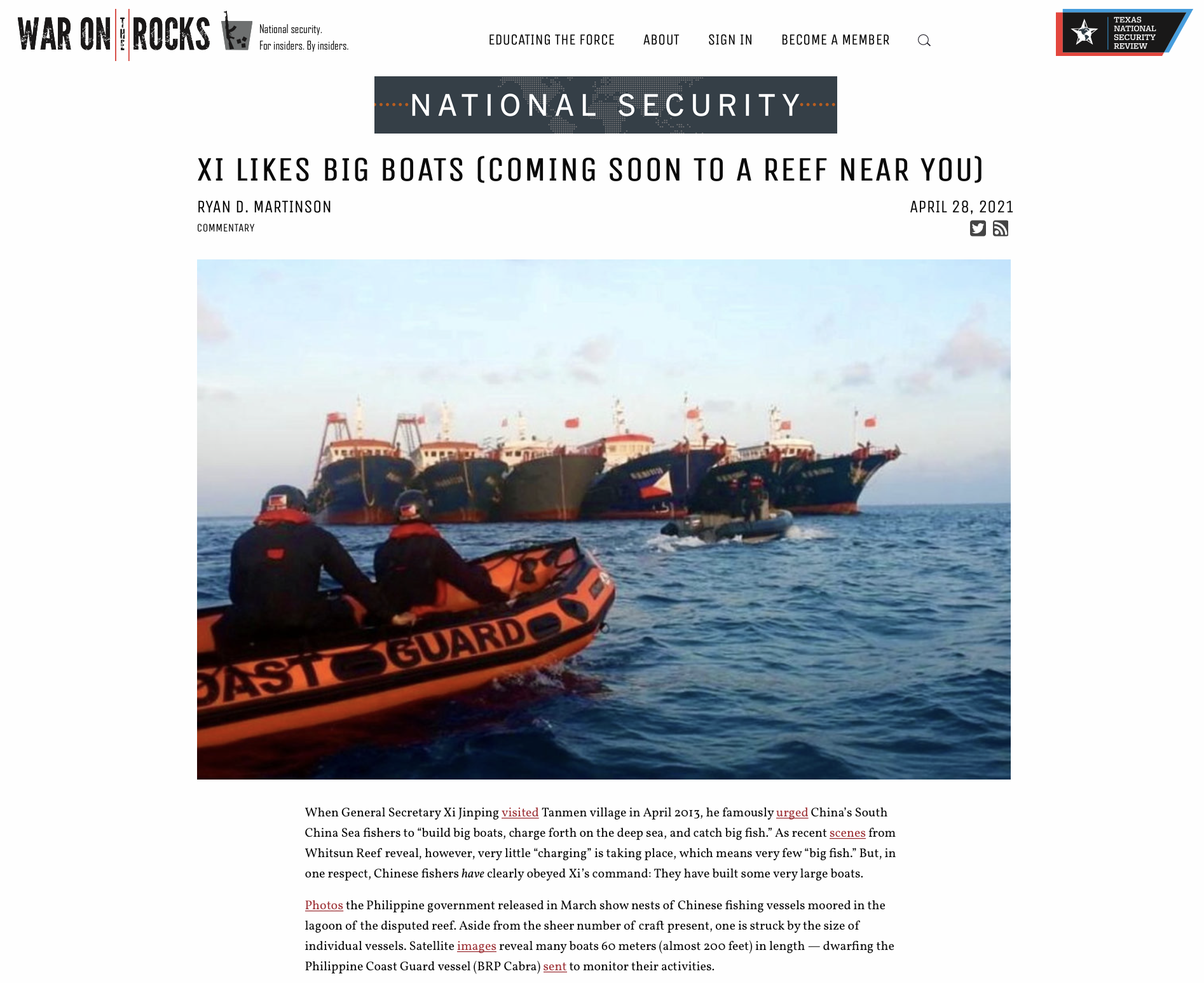

China provides generous financial incentives (including fuel and other subsidies) to Chinese fishers and invests heavily in maritime law enforcement forces to ensure their security.

In recent years, Chinese fishers have been involved in a number of incidents in disputed areas of the East and South China Seas. Their presence in contested space is due to a combination of factors, including the individual initiative of private fishing boat owners and state policies that seek to leverage Chinese fishers to achieve political aims. These factors differ depending on the area in question. This article examines the case of Chinese fishing in the southernmost sections of China’s claims in the South China Sea, in waters that fall within the exclusive economic zones of Indonesia and Malaysia. It argues that while most Chinese fishing in these waters is driven by private fishing boat owners pursuing economic gain, the Chinese government has played a decisive role in enabling and supporting their activities. This article also offers evidence that some PRC fishers operate there at the direction of the Chinese military, in their capacity as members of China’s “maritime militia.”

Chinese fishing in disputed waters in the East and South China Seas is a product of individual initiative and state policy. China’s coastal waters are overfished, so Chinese fishers have economic incentives to operate in areas with greater chance for profit. This includes disputed space. For its part, the central government sees value in their presence there. Aside from contributing to the marine economy, Chinese fishing in disputed space upholds China’s claims to sovereignty and jurisdiction in these areas. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) therefore crafts policies to support—and in some cases, direct—the activities of Chinese fishers operating in contested space [1].

Which of these factors—individual initiative or government policy—is the more important driver? It depends on the area in question. This article examines the circumstances of Chinese fishing activities in one particular area, the “southern Spratlys,” defined as Chinese-claimed waters in the South China Sea south of 6 degrees latitude [2].1 It argues that the Chinese government has played a decisive role in enabling and supporting Chinese fishing in these waters. Moreover, this article also offers evidence that some PRC fishers operate there at the direction of the Chinese military, serving as members of China’s maritime militia.

This article comprises six parts. Part one outlines the known facts of Chinese fishing activities in the southern Spratlys. Part two discusses the economic incentives luring Chinese fishers to the southern Spratlys, and the costs and risks associates with pursuing commercial gain in these waters. Part three examines the factors informing Beijing’s policies for Chinese fishing in the southern Spratlys. Parts four, five, and six analyze the three main prongs of its approach. The paper concludes with a summary of key findings. … … …

Chinese fishing activities in the southern Spratly are largely an outcome of profit-seeking Chinese fishers supported by robust government policies to ensure their security and profitability. However, there is evidence that at least some Guangxi trawlers active in these waters operate at the command of the Chinese military. These vessels and their crews are associated with a paramilitary organization called the “maritime militia” (海上民兵).

Militia-operated fishing boats conduct three main types of maritime rights protection operations [94]. First, they maintain presence in contested areas, to embody China’s claim and collect intelligence. Second, they help escort Chinese oil/gas survey vessels or drilling rigs operating in disputed waters, protecting them from foreign harassment or obstruction. Third, they perform law enforcement-type missions such as expelling foreign fishing vessels or survey ships from Chinese-claimed maritime space. In the southern Spratlys, Chinese militiamen could only be performing the first of these three missions, i.e., targeted pres- ence and intel collection, as China has not pursued oil/gas exploitation here or attempted to expel foreign fishers.

Authoritative sources suggest that Guangxi militiamen conduct rights protection operations in the Spratlys. For example, Qiaogang Town in Yinhai District has at least one maritime militia company. In 2015, it began setting up Chinese Communist Party (CCP) branches on maritime militia vessels heading to the Paracels and the Spratlys. CCP members would lead Chinese fishers to “better safeguard national sovereignty and handle issues that they encounter at sea” [106]. The 2018 Beihai City Almanac indicates that in 2017 the PLA’s Beihai Military Sub-district worked with the Beihai city government to “organize and support” Beihai fishing vessels operating in the Spratly’s southwest fishing grounds. Though the connection was not explicitly made, the sub-district would have almost certainly worked through the maritime militia forces that it oversees [107].41

In sum, there are some indications that Guangxi maritime militia forces operate in the southern Spratlys. However, if they do operate in these waters, their role is limited to presence operations. As the 2018 Beihai almanac suggests, they likely serve as an organizational link between the Chinese military and the rest of fishing fleet. However, there is no evidence to suggest that Chinese maritime militia forces constitute the bulk of the fishing fleet in these waters. Guangxi fishers want to fish here and they are incentivized to do so (Table 1).

[94] (a) Conor Kennedy, The struggle for Blue Territory: Chinese maritime militia grey-zone operations, RUSI J. 163 (5) (2018) 1–12.(b)Zhang Rongsheng, Chen Minghui, Some Thoughts on Organizing and Mobilizing Maritime Militia to Participate in Rights Protection Operations, National Defense, no. 8, 2014, p. 12.

[106] Lu Wei, Jiang Jun, Shen Yangfu, Serving Fishers and Peasants, Party Members Take the Lead, Beihai Daily, July 10, 2015. http://www.pzhhbfn.cn/xwdt/qxdt/yhq/201507/t20150710_1381778.html.

Chinese fishers have operated in the southern Spratlys since the early 1990s. The first expeditions were conducted by vessels from Guangxi’s Beihai city. Beihai fishers continue to dominate Chinese fishing in this area. In 2018, at least 175 Guangxi trawlers operated in these waters, the vast majority from Beihai.

Economic motives are clearly a key driver behind the activities of Guangxi fishers in the southern Spratlys. That is, they go there to catch fish that is unavailable in the same abundance in the Gulf of Tonkin. However, this article shows that government policies have played a decisive role ensuring that these activities are safe and profitable. By implementing robust policy measures, the PRC enables and encourages Guangxi fishers to operate in this highly disputed maritime space.

PRC fisheries policy in the southern Spratlys is largely focused on the political importance of Chinese fishing in these waters. It proceeds from two key beliefs. First, that Chinese fishers have the right to operate in the northern part of the Sunda Shelf because it falls within the nine-dash line. Second, Chinese fishers should operate in the southern Spratlys because their activities serve the political function of upholding China’s claims to maritime rights in these waters. Just by being present there, they demonstrate Chinese sovereignty.

These beliefs drive Beijing’s efforts to support Chinese fishing in these waters. Chinese policymakers heavily subsidize fishing operations in the Spratlys. These subsidies include defraying fixed costs, offsetting fuel costs, and providing other monetary awards to influence the cost-benefit analysis of individual fishing boat owners. Chinese analysts have shown that these incentives are probably the biggest inducements for fishing in the southern Spratlys. Moreover, Chinese policymakers invest huge sums of money to ensure the security of Chinese fishers operating there. They have built dozens of very large law enforcement cutters and charged them with maintaining adequate presence in these waters to deter coastal state EEZ enforcement. Beijing’s efforts have been largely successful: since 2016, Chinese fishing vessels have been able to operate with impunity in the southern Spratlys.

The No 4 dock at Jiangsu Rongsheng Heavy Industries Co Ltd"s Nantong shipbuilding base on May 26, 2012. With a dimension of 139.5*580m,the dock is equipped with a 1600-T gantry crane, the world"s largest. [Photo/chinadaily.com.cn]

China Rongsheng Heavy Industries Group Holdings Ltd, the nation"s largest private shipbuilder, may seek "cooperation with one or two ship builders" in 2013 or 2014, grasping the opportunity emerging from an industry recession, according to Xu Yifei, assistant president of Jiangsu Rongsheng.

In response to this round of recession, Rongsheng has been actively upgrading technology and design. It has also put more focus on the offshore engineering sector to further diversify its business.

Rongsheng is setting up its offshore engineering company in Singapore, aiming to take advantage of Singapore"s technology and existing market to deepen its penetration in the global offshore engineering market, according to Xu.

The company entered the marine engineering sector years ago. China"s first deepwater pipe-laying crane vessel, known as Hai Yang Shi You 201, was built by Rongsheng. The vessel can lay pipes at depths of 3000 meters and lift 4000 metric tons and will operate at the South China Sea"s Liwan 3-1 gas field.

Rongsheng"s president, Chen Qiang, said in an earlier interview that he hoped orders from marine engineering will make up about 40 percent of the company"s new orders this year.

8613371530291

8613371530291