rongsheng petrochemical annual report 2018 made in china

Stocks: Real-time U.S. stock quotes reflect trades reported through Nasdaq only; comprehensive quotes and volume reflect trading in all markets and are delayed at least 15 minutes. International stock quotes are delayed as per exchange requirements. Fundamental company data and analyst estimates provided by FactSet. Copyright © FactSet Research Systems Inc. All rights reserved. Source: FactSet

* China’s Zhejiang Petrochemicals, which is owned by Rongsheng Group, has been awarded a quota to import 5 million tonnes of crude oil this year, a statement from the Zhoushan Bureau of Commerce in Zhejiang province said on Thursday.

* In April, Chinese private chemical producer Hengli Group won import quotas of 400,000 barrels per day (bpd), the largest ever for a private refiner, as it challenges the country’s smaller independent plants in an oversupplied Chinese fuel market. (Reporting by Josephine Mason, Meng Meng and Aizhu Chen Editing by Susan Fenton)

• In 2018-2022, several refining & chemical integration (RCI) projects will be built and commissioned in 7 main petrochemical bases. Changxing Island is one of them;

China is a large country in oil refining, with total capacity of 771.5Mt/a, and 26 oil refining bases of 10Mt/a level. During 13th FYP, China is orderly advancing the construction of Seven Main Petrochemical Bases, namely, Changxing Island (Xizhong Island) in Dalian, Caofeidian in Hebei, Lianyungang in Jiangsu, Caojing in Shanghai, Ningbo Zhenhai (Zhoushan) in Zhejiang, Gulei in Fujian, and Huizhou in Guangdong, which will promote the development of China’s oil refining industry in direction of large-scale unit, refining & chemical integration (RCI), and industry clustering.

China is entering into the peak period of RCI projects construction, and private enterprises become the main force of RCI projects, in order to expand their industrial chain to upstream. Hengli 20Mt/a RCI project and ZPC RCI project plan to be put into operation in 2018; Shenghong 16Mt/a RCI project and Xuyang Petrochemical 15Mt/a RCI project has been approved by Provincial Development and Reform Commission; RCI projects invested by Jinjiang Petrochemical, Xinhua Lianhe Petrochemical, Qianhai Petrochemical, and so on, have signed…

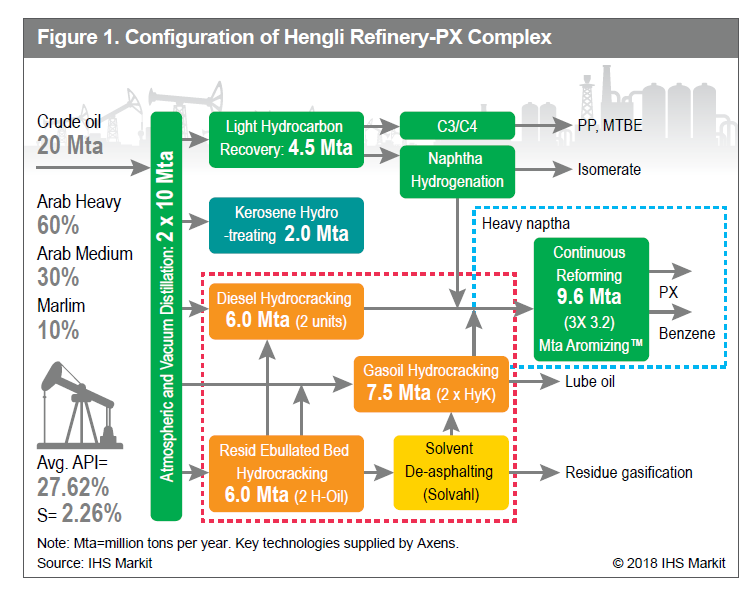

Located in Changxing Island Petrochemical Industrial Base in Dalian, the project of total investment of CNY 56.2bn, is designed with crude oil processing capacity of 20Mt/a and aromatic complex unit nominal scale of 4.5Mt/a (based on PX), to process Saudi heavy oil, Saudi medium oil, Marine crude, and use full hydrogenation process route of atmospheric-vacuum distillation + hydrocracking + aromatics, with hydrogenation capacity of 23Mt/a. Product scheme of the project includes 4.34Mt/a PX, 970kt/a pure benzene, 4.61Mt/a gasoline, 1.61Mt/a diesel, 3.71Mt/a aviation kerosene, 1.63Mt/a chemical light oil, etc.

The project is located in Zhoushan Green Petrochemical Base, with capital investment of CNY 173.08bn, to build total capacity of 40Mt/a oil refining, 8Mt/a PX, 2.8Mt/a ethylene in two phases.

Phase I of the project, with investment of CNY 90.16bn, plans to build 20Mt/a oil refining + 5.2 Mt/a aromatics + 1.4Mt/a ethylene. The oil refining part uses core process flow of “residuum hydrodesulfurization / RFCC + hydrocracking + coking”, while aromatics part uses world-class reforming + PX units, with 1.4Mt/a ethylene unit. Phase I of the project is under construction now, and plans to be put into operation by the end of 2018.

The project is located in Lianyungang Petrochemical Industrial Base, with total investment of CNY 77.65bn, to build 16Mt/a oil refining, 2.8Mt/a PX, 1.1Mt/a ethylene. The project plans to process Saudi light oil, Saudi heavy oil, and use the general process flow scheme of crude oil processing + heavy oil hydrocracking + PX + ethylene cracking + IGCC.

Located in Caofeidian Petrochemical Industrial Base, the project of total investment of CNY 25.94bn, plans to build production units including 15Mt/a atmospheric-vacuum distillation, 2Mt/a aromatics complex, etc. The project will use Kuwait crude oil and Saudi light oil as raw material, and use mature technologies of “atmospheric-vacuum distillation + residuum upgrading + wax oil hydrocracking + aromatics + isomerization” and process route with high value-added products. In Sep 2017, the project was approved by Hebei Provincial Development & Reform Commission.

The project is located in Gulei Petrochemical Industrial Bases, plans to invest about CNY 60bn, and use world-class 10Mt/a crude oil processing technology, with 2.6Mt/a PX and 1.5Mt/a ethylene, but without oil products such as gasoline, diesel and kerosene.

Located in Caofeidian Petrochemical Industrial Base, the project with investment of about CNY 60bn, plans to build the total capacity of 20Mt/a oil refining, 5.57Mt/a aromatics, and 800kt/a PP.

The project with predicted investment of CNY 40bn, plans to be built in Caofeidian Petrochemical Industrial Base, with total capacity of 15Mt/a oil refining, 3Mt/a PX. Contract signing of the project was undertaken in 2015.

In the future, several world-class RCI projects dominated by private enterprises will be built and put in operation, which will improve the scale and competitiveness of China’s refining & chemical industry, promote industrial transformation & upgrading and change from large to strong, as well as expand the industry development space. Besides, RCI projects construction will also improve the situation of large import and high external dependence for basic chemical commodities such as PX, ethylene, etc., as well as high-end petrochemical products, increase the power of discourse in the industry.

The3rd China Refining & Chemical Integration Conference 2018 organized by ASIACHEM will be held on Jun 27-28 in Dalian. Several large scale RCI projects owners will be present, to exchange project progress & planning consideration.

Financial Associated Press, January 12 - Rongsheng Petrochemical announced that the 40 million T / a refining and chemical integration project (phase II) of Zhejiang Petrochemical, a holding subsidiary, was fully put into operation. Up to now, the oil refining, aromatics, ethylene and downstream chemical products units in phase II of the project have been fully put into commissioning, and the whole process has been opened. The company will further improve the commissioning of relevant process parameters and improve the production and operation level.

Thus, the healthiest sales increases seen in the Global Top 50 came from petrochemical companies. Sabic, Formosa Plastics, PetroChina, LyondellBasell Industries, and ExxonMobil Chemical all clocked in with sales increases of 40% or more. Also riding the crest of the commodity price wave are fertilizer makers such as Yara, Nutrien, and Mosaic, which posted astounding increases in sales.

A few companies in the 2021 ranking fell off in 2022 because they didn’t have enough sales to make the cut. These are the US petrochemical maker Westlake, the US agricultural chemical producer Corteva Agriscience, and the Japanese chemical makers Tosoh and DIC.

Two Chinese newcomers make the ranking: TongKun Group at 48 and Hengyi Petrochemical at 50. Both are polyester producers that make their own raw materials. Hengyi also has a large, integrated nylon 6 business. Both companies join similar Chinese firms, like Hengli Petrochemical and Rongsheng Petrochemical. All these companies have been building massive complexes for aromatics and derivatives, in many cases swamping entire segments of the chemical industry—such as purified terephthalic acid—with new capacity that is well beyond the scale of players outside China.

For the third consecutive year, BASF heads the Global Top 50. Because it has a home base in Germany, the company was strongly impacted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. BASF pledged in April to wind down operations in Russia and Belarus, which represent about 1% of its sales. The company says it will continue supplying agrochemicals to these countries to avoid disrupting the world’s delicate food supply chain. BASF has also been affected by the severe increase in European natural gas prices that the war has exacerbated. In March, BASF chairman Martin Brudermüller told a Houston audience at the IHS Markit World Petrochemical Conference that “European industry really has to rethink” its strategy, given its dependence on natural gas from Russia. The war has also affected the company’s Wintershall Dea energy joint venture, which has extensive operations in Russia. During the first quarter, BASF took a $1.2 billion write-off related to the cancellation of Nord Stream 2, a natural gas pipeline between Germany and Russia that Wintershall helped finance. BASF is also anticipating the coming energy transition. The company is carving out its emission catalyst business, which it acquired with its 2006 purchase of Engelhard. The move is a response to the dim outlook for internal combustion engine vehicles and could be a prelude to a sale. BASF has simultaneously been trying to grow as a producer of materials for electric vehicle batteries and aims to spend $5 billion on production capacity outside Europe.

Once again, the blue-chip Chinese firm Sinopec is the second-largest chemical company in the world. Sinopec is working on an enormous lineup of capital expansions in China. Last year in Zhenhai, it started up an ethylene cracker project and began work on a propane dehydrogenation plant that it hopes to finish in 2024. The firm is building a cracker and derivatives project in Tianjin that it expects to complete next year and is bringing another one to completion in Hainan this year. Sinopec is also constructing a massive purified terephthalic acid complex in Yizheng. Like many energy and chemical firms, Sinopec has gotten into the act of carbon abatement. In Zibo earlier this year, it started up a carbon-capture-and-storage project that will handle 1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually.

In 2020, Dow revealed its aspiration to reach carbon emission neutrality by 2050, and at an investor event in October, it detailed its plans to get there. The company aims to spend $1 billion per year, about a third of its capital budget, to decarbonize its petrochemical sites around the world one by one. Topping that list is Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta, where in an industry first, the company will build a carbon-neutral ethylene cracker. An autothermal reformer will process the cracker’s off-gases to generate hydrogen that will be burned in the cracker’s furnaces instead of natural gas. Dow will capture the resulting carbon dioxide and inject it into Alberta’s CO2 pipeline for sequestration. Dow’s sustainability push extends beyond greenhouse gases and into plastic waste. At the October event, for example, the company said it would collaborate with Fuenix Ecogy to build a waste plastics pyrolysis plant in the Netherlands.

The Saudi giant Sabic has a large presence in Europe owing to its acquisition of petrochemical businesses from DSM and Huntsman more than a decade ago. And while the company gained a North American engineering polymer business in 2007 with the purchase of GE Plastics, a US toehold in petrochemicals has been more elusive. Sabic finally accomplished this long-term objective in January when its $10 billion joint venture with ExxonMobil Chemical, Gulf Coast Growth Ventures, started up near Corpus Christi, Texas. The venture produces ethylene and the derivatives polyethylene and ethylene glycol. The project is noteworthy because of how quickly it was erected: in just over 2 years. Some recent US petrochemical projects have experienced delays longer than that.

Formosa Plastics’ proposed $9.4 billion petrochemical complex in St. James Parish, Louisiana, suffered a major setback last year when the US Army Corps of Engineers ordered a full environmental review. That process could take longer than 2 years, according to local activists. The massive project, which would include an ethylene cracker, polyethylene plants, and other facilities, was originally unveiled in 2015. While the complex would be an important diversification move for the Taiwan-based company, S&P Global Ratings noted in a report in October that Formosa’s management could be reaching the end of its patience for delays and local opposition. “We see diminishing probability that the planned mega project in Louisiana will go ahead, given the changing political atmosphere in the U.S.,” the credit rating agency wrote.

Since its inception in the 1990s, Ineos has expanded by acquiring established divisions of large chemical companies. Most recently, in early 2021, it bought BP’s aromatics business, a major producer of purified terephthalic acid, for $5 billion. Since then, Ineos has been focusing on sustainability. In September, it announced a $1.3 billion plan to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 60% at its Grangemouth, Scotland, petrochemical complex by 2030. It will do so by capturing the greenhouse gas and sending it to the proposed Acorn CO2 system, which aims to inject it under the North Sea. In October, Ineos said it plans to spend $2.3 billion on green hydrogen projects. It will construct a 20 MW electrolyzer, powered by alternative energy, in Rafnes, Norway. And in Cologne, Germany, Ineos wants to build a 100 MW electrolyzer that will make hydrogen for green ammonia. Separately, Ineos is installing a unit in Cologne to extract acetonitrile made during acrylonitrile production. Acetonitrile is a solvent used in butadiene extraction and in high-performance liquid chromatography. Its use is acutely growing as a solvent in the production of oligonucleotides for RNA vaccines.

PetroChina heaped on the growth in 2021, expanding by 42% from 2020 as China’s economy recovered from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. New projects in China will only further the company’s expansion. This year, it is due to complete the $10 billion Guangdong Petrochemical project. The massive effort includes a refinery, an aromatics unit, and an ethylene cracker. PetroChina has also finished work on an ethylene project in Tarim that will use domestically produced ethane as its feedstock. In Jieyang, an enormous $1 billion acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene plant with 600,000 metric tons per year of capacity is in the works.

Over the past year, ExxonMobil has been advancing sustainability initiatives. In March, it unveiled plans to build a blue hydrogen facility at its refining and petrochemical complex in Baytown, Texas. The project would capture 10 million metric tons (t) per year of carbon dioxide generated in the hydrogen production process, reducing the site’s carbon footprint by 30%. The project would connect to a massive carbon-capture-and-storage hub in the region that ExxonMobil is spearheading. Also in Baytown, the company is building a facility that will use new chemical technology to recycle waste plastics. It hopes to process 500,000 t of plastics annually around the world by 2026 and is also considering projects in Canada, the Netherlands, and Singapore.

Within a year of taking over the helm of Japan’s largest chemical maker, CEO Jean-Marc Gilson, a veteran of Dow Corning and Roquette, launched a major restructuring initiative. Mitsubishi Chemical Group plans to carve out its petrochemical and coal-based chemical businesses as a separate company and then exit them by the end of its 2023 fiscal year. The units, which make olefins, polyolefins, and other bulk petrochemicals, generate about 20% of the company’s sales. Mitsubishi Chemical Group wants to focus on more specialized areas, such as electronic materials and the life sciences.

The expansion program at this Chinese firm is a good illustration of just how massively and systematically the Chinese petrochemical industry has been growing in recent years. For example, Hengli Petrochemical plans to bring on line 5 million metric tons (t) per year of capacity for the polyester raw material purified terephthalic acid (PTA) later this year in Huizhou, China. The company is building a 450,000 t plant to make poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT), which will consume some of the PTA as a raw material. Hengli is building a 300,000 t adipic acid unit, also to help feed PBAT production. And it is working on a big polyester fiber expansion and recently opened a large ethylene cracker.

Like its industrial gas rivals Air Liquide and Air Products, Linde is focused on carbon reduction. In May, the German firm and BP announced that they would collaborate on a large carbon-capture-and-storage project on the Texas Gulf Coast. The firms aim to make blue hydrogen, produced by reforming natural gas and storing the by-product carbon dioxide. Linde will distribute this hydrogen to customers via its regional pipeline network. The firms aim to store some 15 million metric tons of CO2 annually in underground formations. In Austria, Linde is building a plant to make green hydrogen—derived from water electrolysis powered by renewable energy—for sale to the semiconductor maker Infineon Technologies. To help shore up helium supply, Linde is adding an extraction unit at a natural gas liquefaction plant in Texas. The project will increase the world’s supply of helium by more than 3%.

Late last year, the French industrial gas giant Air Liquide got into a business that is as high tech as a chemical business can get. It signed an agreement with the Canadian nuclear power operator Laurentis Energy Partners to buy helium-3, a light isotope of helium formed via the β decay of the heavy hydrogen isotope tritium. Air Liquide will market 5,000–10,000 L of the 3He annually. The isotope is needed for quantum computing, which must operate at temperatures as close to absolute zero as possible. Conventional liquid 4He cooling can get down to 1–4 K, and getting below that requires mixing in some 3He. Separately, Air Liquide is building what it calls the world’s largest biomethane plant, at a Chicago-area landfill. The industrial gas maker estimates that the collected methane could generate 380 GW h of energy annually. It is also building a methane recovery plant in Wisconsin.

The Indian conglomerate has abandoned plans to put its refining and chemical operations—which it calls Oil to Chemicals—into a stand-alone business. It also walked away from negotiations with Saudi Aramco to sell a 20% stake in the business for $15 billion. Instead, Reliance Industries is undertaking what may turn out to be an even bigger change in direction. Last year, it announced an ambitious goal to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2035. Reliance is setting aside 2,000 hectares of land at its massive Jamnagar refinery and petrochemical complex for factories that would make photovoltaic modules, batteries, electrolyzers, and fuel cells. Along these lines, Reliance bought Faradion, a British sodium-ion battery start-up, for $135 million. It will spend another $35 million to bring the new battery chemistry to market. It also purchased the Norwegian solar cell maker REC Group for $771 million.

The Chinese polyurethane and petrochemical maker has been rocketing up the Global Top 50 because of its prodigious growth in recent years. And 2021 was another enormous year for Wanhua Chemical—its revenues nearly doubled from 2020. Ambitious capital expansion projects have helped fuel the growth. In Yantai, China, it opened an ethylene cracker and derivatives plants and revamped methylene diphenyl diisocyanate production. In April, the company announced it would spend $3.6 billion to build a chemical complex in Penglai, China. The project, to be completed in 2024, will feature a propane dehydrogenation unit as well as downstream plants for polypropylene, propylene oxide, and other chemicals. The company also started producing cathode materials and the biodegradable polymer poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate).

It is possible that Braskem could change hands in the near future. Novonor, the Brazilian conglomerate formerly known as Odebrecht, is facing hefty fines because of a Brazilian corruption scandal. The US Department of Justice alone is demanding $2.6 billion from the company. As a consequence, Novonor has been looking to sell its 38% interest in Braskem, which includes control of more than 50% of Braskem’s common stock. Sale talks are nothing new for Braskem. The company discussed a sale to LyondellBasell Industries in 2018 and 2019, but nothing came of the negotiations. In 2020, Novonor and Braskem’s other major shareholder, the Brazilian state oil company Petrobras, planned to float Braskem shares on public markets. That plan was shelved earlier this year because of financial market volatility. And in April, the private equity firm Apollo Capital was rumored to be bidding for Novonor’s stake.

A Rongsheng Petrochemical subsidiary, Zhejiang Petroleum & Chemical, started up the second phase of its massive refining and petrochemical complex in Zhejiang, China, in 2021. With capacity now doubled, the facility can process 40 million metric tons (t) of oil per year. The facility has a large petrochemical output: up to 6.6 million t of aromatics and 1.4 million t of ethylene per year. The expansion allowed the company to start making specialized polymers, such as acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene and polycarbonate.

The Thai polyester maker Indorama Ventures made another big acquisition to diversify its business earlier this year when it bought the ethoxylated surfactant maker Oxiteno from the Brazilian conglomerate Ultrapar Participações for $1.3 billion. Oxiteno has about $1 billion in annual sales. In 2020, Indorama bought Huntsman’s US-based surfactant unit, its first big move into surfactants. Indorama, already a big mechanical recycler of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), is plunging into the chemical recycling of plastics. It plans to build a plant in Longlaville, France, that will depolymerize PET using an enzymatic process from the start-up Carbios. The facility will be close to an Indorama PET plant.

Solvay, one of Europe’s oldest chemical companies, plans to split in two. The larger of the two resulting firms would house its specialty polymers, aerospace composites, consumer ingredients, and aroma chemical businesses and have $6.6 billion in annual sales. The other would have $4.5 billion in sales and make commodity chemicals such as soda ash and peroxides. The move builds on a company plan announced in 2021 to carve out and possibly sell its soda ash business. The bigger split-up scheme got pushback from financial analysts, who questioned the advantages of combining businesses as varied as aerospace materials and consumer product ingredients. Solvay executives responded that specialty chemical businesses bear similarities, such as their appetite for capital allocation.

Over the past year, Arkema has placed a lot of emphasis on one of its core businesses, adhesives, as well as on an emerging business, battery materials. The French specialty chemical maker bought Ashland’s adhesives business in February for $1.65 billion. The business has $360 million in annual sales of water-based polyurethane wood glues and acrylic, pressure-sensitive adhesives for packaging labels and other applications. In 2015, Arkema bought the adhesives maker Bostik from Total for $2.2 billion. With Nippon Shokubai, Arkema is studying the feasibility of producing lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide electrolyte salts, used in next-generation batteries, in France. Arkema’s goal is to have sales to the battery market of at least $1 billion per year by 2030. To that end, it is also expanding capacity for poly(vinylidene fluoride) in Pierre-Bénite, France. The polymer is used as a binder and separator material in lithium-ion batteries.

Asahi Kasei has been making a push into biobased chemicals. It plans to make the building-block chemical acrylonitrile from biomass-derived propylene at its Tongsuh Petrochemical subsidiary in South Korea. It will use a mass-balance approach, in which biomass fed into a conventional petrochemical plant is credited to a share of products that are made. And at a conference in Washington, DC, in March, company officials said Asahi would commercialize nylon 6,6 made with biobased hexamethylenediamine from Genomatica. Meanwhile, the Japanese company is exiting one of its old-line operations. In August, the company said it was leaving the clear styrene block copolymer business by 2023 because of deteriorating profitability.

Johnson Matthey (JM) is trying to find its footing. The British firm makes precious-metal catalysts for catalytic converters and is thus heavily reliant on internal combustion automotive engines, which face a bleak long-term outlook. The company has also been exiting noncore businesses. In June, it closed a deal to sell its pharmaceutical chemical business to the private equity firm Altaris Capital Partners for $430 million. The firm is retaining a 30% stake in the business, which generates more than $300 million in sales annually. Additionally, JM is selling its European battery material operations to Australia’s EV Metals Group and a battery material plant in Canada to Nano One Materials. But a possibility remains that JM itself will change hands. In April, US industrial firm Standard Industries revealed purchased a 5% stake in the company. Machinations like this often foretell a takeover. Standard bought another catalyst firm, W. R. Grace, in 2021.

In a transaction that will allow it to focus strictly on petrochemicals and polymers, Borealis received an $870 million offer in June for its nitrogen fertilizer business from the Czech agricultural conglomerate Agrofert. The business had sales of about $1.5 billion in 2021. The deal works out nicely for Borealis, which had an earlier overture of $520 million from EuroChem Group. Borealis walked away from that deal because of the war in Ukraine and EuroChem’s Russian connections. Borealis might have missed an opportunity to be affiliated with a high-end polymer business. OMV, the Austrian refiner that owns 75% of Borealis, put in a bid to purchase DSM’s engineering polymer business. But OMV lost out to a partnership between Advent International and Lanxess.

PTT Global Chemical rejoins the Global Top 50 after a 1-year absence. The Thai petrochemical maker made a major diversification play late last year when it purchased the German coatings resins maker Allnex for $4.8 billion from the private equity firm Advent International. Allnex has annual sales of about $2.4 billion. PTT’s backing, Allnex management hopes, will help it expand into Asia. In the US, PTT has had a large petrochemical complex on the drawing board since 2015. But its air permits from the state of Ohio expired in February. The company said at the time that it was seeking new permits that aligned with its goals of achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. It subsequently unveiled a plastics recycling project for the state.

The main issue at Sasol for several years was a petrochemical complex in Lake Charles, Louisiana, that went $4 billion over budget and led to a major management shake-up. Another recent setback for the firm came in November, when South African regulators blocked the sale of its business in sodium cyanide to Draslovka, already a strong player in that field. Now there are signs of green shoots at the South African firm. Sasol and South Korea’s Lotte Chemical are studying the construction of a plant to make battery electrolyte solvents in Lake Charles or at Sasol’s complex in Marl, Germany. Sasol would provide the raw materials.

Lanxess is planning a likely exit from the polymer business. The German company and the private equity firm Advent International formed a joint venture to buy DSM’s engineering polymer business—a producer of high-end nylon resins—for $4.1 billion. Lanxess is contributing its own business, which makes polybutylene terephthalate and nylon 6, to the partnership. It will own an up to 40% stake in the joint venture for 3 years, after which it will have an option to sell. At the same time, Lanxess is growing in specialty chemicals. Earlier this month, it completed the purchase of International Flavors & Fragrances’ microbial control business for about $1.3 billion. The business, which once belonged to Dow, makes glutaraldehyde biocides and isothiazolinone-based antimicrobials and has $450 million in annual sales.

This is the first year in the Global Top 50 for Hengyi Petrochemical, a Chinese firm that primarily makes polyester and nylon 6. Hengyi affiliates recently started a massive refining and petrochemical complex in Brunei. The 2.1 million metric tons per year of p-xylene and benzene made in this new complex is being sent to China for conversion into the polyester raw material purified terephthalic acid and the nylon precursor caprolactam. The company is planning a second phase of the Brunei project, which will include an ethylene cracker and derivatives units.

Privately owned unaffiliated refineries, known as “teapots,”[3] mainly clustered in Shandong province, have been at the center of Beijing’s longtime struggle to rein in surplus refining capacity and, more recently, to cut carbon emissions. A year ago, Beijing launched its latest attempt to shutter outdated and inefficient teapots — an effort that coincides with the emergence of a new generation of independent players that are building and operating fully integrated mega-petrochemical complexes.[4]

Meanwhile, as teapots expanded their operations, they took on massive debt, flouted environmental rules, and exploited taxation loopholes.[12] Of the refineries that managed to meet targets to cut capacity, some did so by double counting or reporting reductions in units that had been idled.[13] And when, reversing course, Beijing revoked the export quotas allotted to teapots and mandated that products be sold via state-owned companies, it trapped their output in China, contributing to the domestic fuel glut.

The politics surrounding this new class of greenfield mega-refineries is important, as is their geographical distribution. Beijing’s reform strategy is focused on reducing the country’s petrochemical imports and growing its high value-added chemical business while capping crude processing capacity. The push by Beijing in this direction has been conducive to the development of privately-led mega refining and petrochemical projects, which local officials have welcomed and staunchly supported.[20]

Yet, of the three most recent major additions to China’s greenfield refinery landscape, none are in Shandong province, home to a little over half the country’s independent refining capacity. Hengli’s Changxing integrated petrochemical complex is situated in Liaoning, Zhejiang’s (ZPC) Zhoushan facility in Zhejiang, and Shenghong’s Lianyungang plant in Jiangsu.[21]

But with the start-up of advanced liquids-to-chemicals complexes in neighboring provinces, Shandong’s competitiveness has diminished.[23] And with pressure mounting to find new drivers for the provincial economy, Shandong officials have put in play a plan aimed at shuttering smaller capacity plants and thus clearing the way for a large-scale private sector-led refining and petrochemical complex on Yulong Island, whose construction is well underway.[24] They have also been developing compensation and worker relocation packages to cushion the impact of planned plant closures, while obtaining letters of guarantee from independent refiners pledging that they will neither resell their crude import quotas nor try to purchase such allocations.[25]

To be sure, the number of Shandong’s independent refiners is shrinking and their composition within the province and across the country is changing — with some smaller-scale units facing closure and others (e.g., Shandong Haike Group, Shandong Shouguang Luqing Petrochemical Corp, and Shandong Chambroad Group) pursuing efforts to diversify their sources of revenue by moving up the value chain. But make no mistake: China’s teapots still account for a third of China’s total refining capacity and a fifth of the country’s crude oil imports. They continue to employ creative defensive measures in the face of government and market pressures, have partnered with state-owned companies, and are deeply integrated with crucial industries downstream.[26] They are consummate survivors in a key sector that continues to evolve — and they remain too important to be driven out of the domestic market or allowed to fail.

In 2016, during the period of frenzied post-licensing crude oil importing by Chinese independents, Saudi Arabia began targeting teapots on the spot market, as did Kuwait. Iran also joined the fray, with the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) operating through an independent trader Trafigura to sell cargoes to Chinese independents.[27] Since then, the coming online of major new greenfield refineries such as Rongsheng ZPC and Hengli Changxing, and Shenghong, which are designed to operate using medium-sour crude, have led Middle East producers to pursue long-term supply contracts with private Chinese refiners. In 2021, the combined share of crude shipments from Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, and Kuwait to China’s independent refiners accounted for 32.5%, an increase of more than 8% over the previous year.[28] This is a trend that Beijing seems intent on supporting, as some bigger, more sophisticated private refiners whose business strategy aligns with President Xi’s vision have started to receive tax benefits or permissions to import larger volumes of crude directly from major producers such as Saudi Arabia.[29]

The shift in Saudi Aramco’s market strategy to focus on customer diversification has paid off in the form of valuable supply relationships with Chinese independents. And Aramco’s efforts to expand its presence in the Chinese refining market and lock in demand have dovetailed neatly with the development of China’s new greenfield refineries.[30] Over the past several years, Aramco has collaborated with both state-owned and independent refiners to develop integrated liquids-to-chemicals complexes in China. In 2018, following on the heels of an oil supply agreement, Aramco purchased a 9% stake in ZPC’s Zhoushan integrated refinery. In March of this year, Saudi Aramco and its joint venture partners, NORINCO Group and Panjin Sincen, made a final investment decision (FID) to develop a major liquids-to-chemicals facility in northeast China.[31] Also in March, Aramco and state-owned Sinopec agreed to conduct a feasibility study aimed at assessing capacity expansion of the Fujian Refining and Petrochemical Co. Ltd.’s integrated refining and chemical production complex.[32]

Commenting on the rationale for these undertakings, Mohammed Al Qahtani, Aramco’s Senior Vice-President of Downstream, stated: “China is a cornerstone of our downstream expansion strategy in Asia and an increasingly significant driver of global chemical demand.”[33] But what Al Qahtani did notsay is that the ties forged between Aramco and Chinese leading teapots (e.g., Shandong Chambroad Petrochemicals) and new liquids-to-chemicals complexes have been instrumental in Saudi Arabia regaining its position as China’s top crude oil supplier in the battle for market share with Russia.[34] Just a few short years ago, independents’ crude purchases had helped Russia gain market share at the expense of Saudi Arabia, accelerating the two exporters’ diverging fortunes in China. In fact, between 2010 and 2015, independent refiners’ imports of Eastern Siberia Pacific Ocean (ESPO) blend accounted for 92% of the growth in Russian crude deliveries to China.[35] But since then, China’s new generation of independents have played a significant role in Saudi Arabia clawing back market share and, with Beijing’s assent, have fortified their supply relationship with the Kingdom.

Meanwhile, though, enticed by discounted prices Chinese independents in Shandong province have continued to scoop up sanctioned Iranian oil, especially as their domestic refining margins have thinned due to tight regulatory scrutiny. In fact, throughout the period in which Iran has been under nuclear-related sanctions, Chinese teapots have been a key outlet for Iranian oil, which they reportedly unload from reflagged vessels representing themselves as selling oil from Oman and Malaysia.[38] China Concord Petroleum Company (CCPC), a Chinese logistics firm, remained a pivotal player in the supply of sanctioned oil from Iran, even after it was blacklisted by Washington in 2019.[39] Although Chinese state refiners shun Iranian oil, at least publicly, because of US sanctions, private refiners have never stopped buying Iranian crude.[40] And in recent months, teapots have been at the forefront of the Chinese surge in crude oil imports from Iran.[41]

Vertical integration along the value chain has become a global trend in the petrochemical industry, specifically in refining and chemical operations. China’s drive to self-sufficiency in chemicals is a key factor powering this worldwide trend.[42] And it is the emergent “second generation” of independent refiners that it is helping make China the frontrunner in developing massive liquids-to-chemicals complexes. Following Beijing’s lead, Shandong officials appear determined to follow this trend rather than risk being left in its wake.

As Chinese private refiners’ number, size, and level of sophistication has changed, so too have their roles not just in the domestic petroleum market but in their relations with Middle East suppliers. Beijing’s import licensing and quota policies have enabled some teapot refiners to maintain profitability and others to thrive by sourcing crude oil from the Middle East. For their part, Gulf producers have found Chinese teapots to be valuable customers in the spot market in the battle for market share and, especially in the case of Aramco, in the effort to capture the growth of the Chinese domestic petrochemicals market as it expands.

8613371530291

8613371530291