rongsheng refinery 2019 made in china

SINGAPORE, Oct 14 (Reuters) - Rongsheng Petrochemical, the trading arm of Chinese private refiner Zhejiang Petrochemical, has bought at least 5 million barrels of crude for delivery in December and January next year in preparation for starting a new crude unit by year-end, five trade sources said on Wednesday.

Rongsheng bought at least 3.5 million barrels of Upper Zakum crude from the United Arab Emirates and 1.5 million barrels of al-Shaheen crude from Qatar via a tender that closed on Tuesday, the sources said.

Rongsheng’s purchase helped absorbed some of the unsold supplies from last month as the company did not purchase any spot crude in past two months, the sources said.

Zhejiang Petrochemical plans to start trial runs at one of two new crude distillation units (CDUs) in the second phase of its refinery-petrochemical complex in east China’s Zhoushan by the end of this year, a company official told Reuters. Each CDU has a capacity of 200,000 barrels per day (bpd).

Zhejiang Petrochemical started up the first phase of its complex which includes a 400,000-bpd refinery and a 1.2 million tonne-per-year ethylene plant at the end of 2019. (Reporting by Florence Tan and Chen Aizhu, editing by Louise Heavens and Christian Schmollinger)

2 Min ReadFILE PHOTO: Workers are seen at the damaged Saudi Aramco oil facility in Abqaiq, Saudi Arabia, September 20, 2019. REUTERS/Stephen Kalin/File Photo

“There was an adjustment in September but operations are back to normal in October,” Meng Fanqiu who heads Rongsheng International Trading Co in Singapore told Reuters. The trading unit procures crude for the refinery.

Zhejiang Petrochemical, 51% owned by Rongsheng Holdings, operates a 400,000 barrels per day refinery, built on an island off the archipelago city of Zhoushan in east China. The refinery is integrated with a petrochemical complex led by a 1.2 million-tonne per year ethylene facility.

Textile giants Rongsheng and Hengli have shaken up China"s cozy, state-dominated oil market this year with the addition of close to 1mn b/d of new crude distillation capacity and vast, integrated downstream complexes. Petrochemical products, rather than conventional road fuels, are the driving force for this new breed of private sector refiner. And more are on their way.

Tom: And today we are discussing the advent of petrochemical refineries in China, refineries that have been built to produce mainly petrochemical feedstocks. Just a bit of background here, these two big new private sector firms, Rongsheng and Hengli, have each opened massive, shiny new 400,000 b/d refineries in China this year. Hengli at Changxing in Northeast Dalian and Rongsheng at Zhoushan in Zhejiang Province on the East coast. For those unfamiliar with Chinese geography, Dalian is up by China"s land border with North Korea and Zhoushan is an island across the Hangzhou Bay from Shanghai. And the opening of these two massive new refineries by chemical companies is shaking up China"s downstream market. But China is a net exporter of the core refinery products, gasoline, diesel, and jet. So, building refineries doesn"t sound like a purely commercial decision. Is it political? What"s behind it? How will it affect the makeup of China"s petrochemical product imports?

Chuck: And clearly, the driver here for Rongsheng and Hengli, who as Tom mentioned, are chemical companies, they are the world"s largest producers of purified terephthalic acid, known as PTA, which is the main precursor to make polyester, polyester for clothing and PET bottles. And each of them were importing massive amounts of paraxylene, paraxylene being the main raw material to make PTA. And paraxylene comes from the refining of oil. And really the alternate value for paraxylene or its precursors would be to blend into gasoline to increase octane. So, when looking to take a step upstream in terms of reverse or vertical integration, they"ve quickly found themselves not just becoming paraxylene producers, but in fact becoming refiners of crude to begin with, which of course, is quite complex and it involves all kinds of co-products and byproducts. And as many know, the refining of oil, the primary driver there, as Tom has mentioned, is to produce motor fuels. So, we"re reversing this where the petrochemicals become the strategic product and we look to optimize or maybe even limit the amount of motor fuels produced.

Chuck: And margins, of course, as well because no one wants to shut down their unit just to accommodate the new Chinese production. And what remains to be seen is global operating rates for these PX units will be reduced to maybe unsustainable levels. And as margins come down, they"ll be down for everyone, but the most efficient suppliers or producers will be the ones that survive. And in the case of Hengli and Rongsheng, low feedstock costs, if you"re driving down the cost of paraxylene, you take the benefit on the polyester side because now you have very competitive or very low-priced feedstock.

Tom: That"s a really interesting point actually. Looking at it from a refining economics point of view, if you were trying to diversify your revenue stream, for example, you probably wouldn"t want to increase your gasoline production. And gasoline margins in Europe are barely breaking even, they"re about $4 a barrel. In China, gasoline crack spreads are actually negative. So, fine, they"re self-sufficient in the paraxylene they need for weaving, but are they just... the refiners themselves, Hengli and Changxing, are they now just soaking up losses from the sales of their transport fuels? I think they may be initially, but they"re not just giving their gasoline away, obviously, these refineries were conceived as viable commercial concerns. Hengli anticipates profits, I think, of around 12 billion Yuan per year from its Changxing refinery giving a payback period on that investment of around five years. And each company, interestingly enough, has a distinct marketing strategy for their transport fuel.

Rongsheng is trying to build itself into a retail brand around Shanghai and the Zhejiang area. And Hengli is trying to muscle into the wholesale market on a national level, so it"s gonna be selling products across China. And in that respect, as we were discussing earlier, in fact, Rongsheng appears to have an advantage because where it"s located on the East Coast of China, that region is net short still of transport fuels, but Hengli in the Northeast, that"s a very competitive refining environment. It"s a latecomer to an already pretty saturated market: PetroChina, a state-owned oil giant, is a huge refiner up in Northeast China with its own oil fields, so a ready-made source of low-cost crude. And it"s also very close to the independent sector refining hub in Shandong Province, which is the largest concentration of refineries in China. So, I think there are definite challenges for them on the road fuel front, even if it sounds like they"re going to be pretty competitively placed further downstream in the paraxylene market.

Tom: Well, that"s one of the peculiarities of the Chinese market. As private sector companies, neither Rongsheng nor Hengli are allowed currently to export transport fuels. That"s a legacy concern of the Chinese government to ensure energy self-sufficiency downstream to make sure there"s adequate supply on the domestic market of those fuels. So, that is a real impediment for them. And when they ramp up production of gasoline, diesel, and jet, they are driving down domestic prices and they are essentially forcing product into the seaborne market produced by other refineries. So, in that respect, the emergence of Hengli in Northeast China on PetroChina"s doorstep has created a huge new sense of competition for PetroChina in particular. And I think certainly when you look at their recent financial data, it"s quite clear that they are struggling to adapt to the new environment in which it"s essentially export or die, because these new, massive refineries are crushing margins inside China.

Chuck: And going back specifically to the Hengli and Rongsheng projects, it"s interesting to note, again, going to an order of magnitude or perspective, Hengli is producing or has capacity to produce 4.5 million tons of paraxylene. And in phase one, Rongsheng will have capacity to produce 4 million tons. And I know those are just large numbers, but again, bear in mind that last year, global demand was 43.5 million. So, effectively, these two plants, they could account for 20% of global demand. Just these two projects themselves to give you an idea of just how massive they are and how impactful they can be. Impactful or disruptive, it remains to be seen.

Tom: A sign it doesn"t do things by halves. Although that said, one of the interesting things they have done is essentially halved their transport fuel yields. So, where in a conventional refinery, your combined output of gasoline, diesel, and jet, those core products, might be in the region of 80%, when you look at these new refineries, they"ve really cut that back down to 40% or 50%. And there are new petrochemical refineries springing up, and it"ll be very interesting to see how disruptive those are to the petrochemical market. But in the conventional refining market, they are, I think under pressure to do even more to reduce their exposure to already weakened gasoline and diesel markets. I mean, Shenghong — this new textile company who"s starting up another massive new conventional refinery designed to produce petrochemical products in 2021, I think — they"ve managed to reduce that combined yield to around 30%. They"ve reduced that from an original blueprint.

Chuck: It"s remarkable, but just a note of caution, there have been other petrochemical and refinery projects built recently in Saudi Arabia and in Malaysia, in particular, with established engineering and established chemical and refining companies. And they"ve had trouble meeting the targeted dates for startup and it"s one thing to be mechanically complete, it"s another thing to be operationally complete. But both Hengli and Rongsheng have amazed me at how fast they were able to complete these projects. And by all reports so far, they are producing very, very effectively, but it does remain to be seen why these particular projects are able to run whereas the Aramco projects in Malaysia and in Rabigh in Saudi Arabia have had much greater problems.

Tom: It sounds like in terms of their paraxylene production, they are going to be among the most competitive in the world. They have these strategies to cope with oversupplied markets and refined fuels, but there is certainly an element of political support which has enabled them to get ahead of the pack, I guess. And suddenly in China, Prime Minister Li Keqiang visited the Hengli plant shortly after it came on stream in July, and Zhejiang, the local government there is a staunch backer of Rongsheng"s project. And Zhoushan is the site of a national government initiative creating oil trading and logistics hub. Beijing wants Zhoushan to overtake Singapore as a bunkering location and it"s one of the INE crude futures exchanges, registered storage location. So, both of these locations in China do enjoy a lot of political support, and there are benefits to that which I think do allow them to whittle down the lead times for these mega projects.

Zhejiang Petrochemical operates the Dayushan Island refinery, which is located in Zhejiang, China. It is an integrated refinery owned by Zhejiang Rongsheng Holding Group, Tongkun Group, Jihua Group, and others. The refinery, which started operations in 2019, has an NCI of 12.06.

Information on the refinery is sourced from GlobalData’s refinery database that provides detailed information on all active and upcoming, crude oil refineries and heavy oil upgraders globally. Not all companies mentioned in the article may be currently existing due to their merger or acquisition or business closure.

China"s private refiner Zhejiang Petroleum & Chemical is set to start trial runs at its second 200,000 b/d crude distillation unit at the 400,000 b/d phase 2 refinery by the end of March, a source with close knowledge about the matter told S&P Global Platts March 9.

ZPC cracked 23 million mt of crude in 2020, according the the source. Platts data showed that the utilization rate of its phase 1 refinery hit as high as 130% in a few months last year.

Started construction in the second half of 2019, units of the Yuan 82.9 billion ($12.74 billion) phase 2 refinery almost mirror those in phase 1, which has two CDUs of 200,000 b/d each. But phase 1 has one 1.4 million mt/year ethylene unit while phase 2 plans to double the capacity with two ethylene units.

With the entire phase 2 project online, ZPC expects to lift its combined petrochemicals product yield to 71% from 65% for the phase 1 refinery, according to the source.

Zhejiang Petroleum, a joint venture between ZPC"s parent company Rongsheng Petrochemical and Zhejiang Energy Group, planned to build 700 gas stations in Zhejiang province by end-2022 as domestic retail outlets of ZPC.

Established in 2015, ZPC is a JV between textile companies Rongsheng Petrochemical, which owns 51%, Tongkun Group, at 20%, as well as chemicals company Juhua Group, also 20%. The rest 9% stake was reported to have transferred to Saudi Aramco from the Zhejiang provincial government. But there has been no update since the agreement was signed in October 2018.

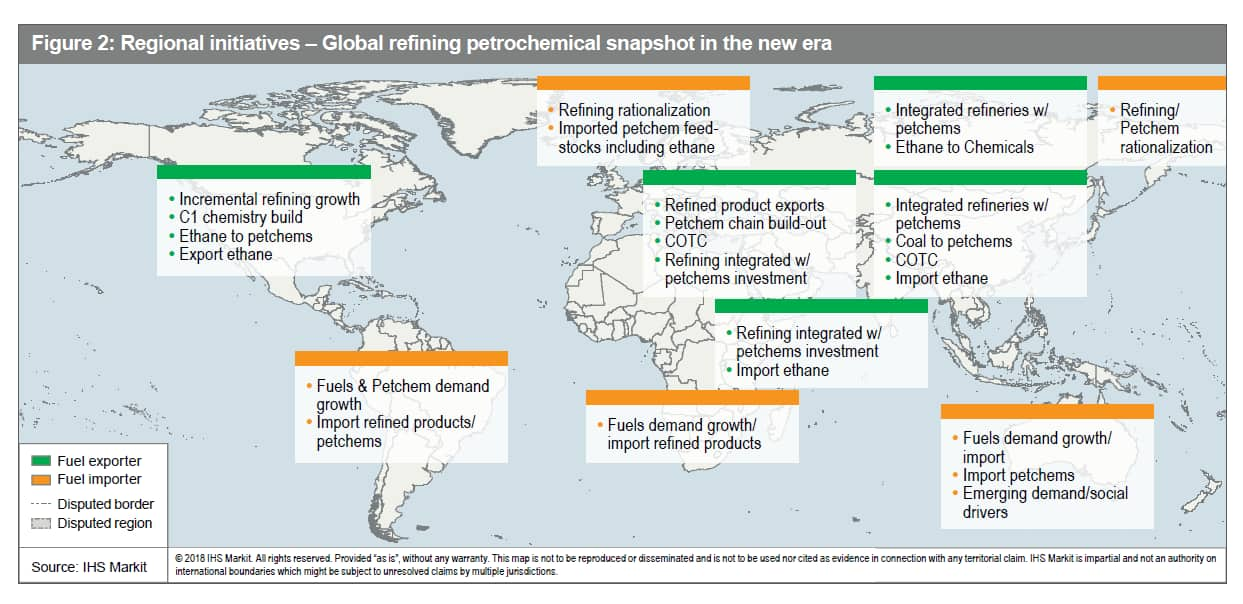

Refinery based crude oil-to-chemicals (COTC) technology involves configuring a refinery to produce maximum chemicals instead of traditional transportation fuels. COTC complexes elevate petrochemical production to an unprecedented refinery scale. Due to the huge scale as well as the amount of target chemicals each COTC complex produces, COTC technology is expected to be disruptive, in terms of abrupt supply increase and price fluctuation, to the global petrochemical industry when each project starts. COTC is happening now with three refinery-PX projects, Hengli (Dalian, China), Zhejiang Phase 1(Zhejiang China), and Hengyi (Brunei) starting in 2019.

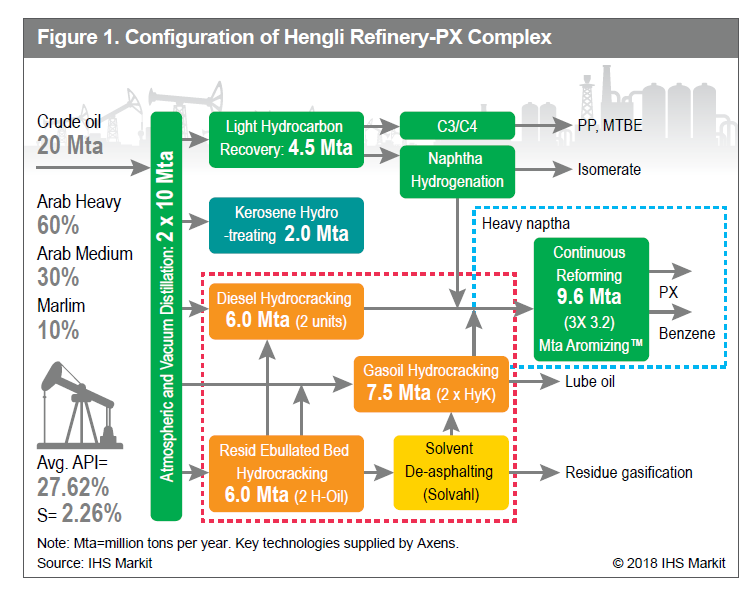

Hengli announced on May 17, 2019 that its COTC refinery-PX complex had achieved full line trial production. The complex is expected to produce 4.34 million tons of PX (paraxylene) per year, in addition to 3.9 million tons of other chemicals. The total chemical conversion per barrel of oil is estimated to be 42%. Hengli’s configuraton is mainly based on hydrocracking of diesel, gas oil, and vacuum residue with technologies licensed from Axens. PEP Report 303, published in December 2018, analyzed Hengli Petrochemical’s refinery-PX complex, provided PEP’s independent analysis of the process configuration and production economics.

Zhejiang Petroleum and Chemical (ZPC) Co.’s COTC refinery-PX project has two phases. Phase 1 is close to completion with several units in the intial trial operation. During the recent visit by S&P Global on May 23, 2019 to Rongsheng, the majority share holder of ZPC, said that full operation is expected in the third quarter of 2019. When completed, Phase 1 is expected to produce 4.0 million tons of PX, 1.5 million tons of benzene, 1.4 million tons of ethylene, and other downstream petrochemicals. The total chemical conversion per barrel of oil is about 45%.

ZPC’s configuration is mainly based on diesel hydrocracking with technology licensed from Chevron and gasoil hydrocracking with technology licensed from UOP. For vacuum residue upgradation, ZPC uses Delayed Coking (open art) and Residue Desulfurization followed by Residue Fluid Catalytic Cracking (RFCC) licensed from UOP. The Phase 2 project construction has also started, and when completed it will have a similar scale to Phase 1. However, the Phase 2 refinery configuration will be further enhanced by UOP to produce more mixed feeds to support two word-scale steam crackers as compared to one cracker for Phase 1. The total chemical conversion has been announced to increase to 50%, up from 45% in Phase 1. The number of downstream petrochemical units is also expected to differ from Phase 1.

The objective of this report (PEP 303A) is to analyze ZPC’s Phase 1 refinery-PX complex. Although Zhejiang Phase 1 project, as announced, includes a steam cracker and fifteen downstream petrochemical units, PEP 303A analysis will draw a boundary before steam cracker to focus on PX production economics to be compared to that of Hengli’s complex.

Section 1 introduces various crude oil-to-chemicals (COTC) approaches including directly feeding a light crude to steam cracker and configuring a refinery to produce maximum chemicals. In this section, we have discussed the merits and impacts of each approach, and why COTC is different from the conventional state-of-art refinery-petrochemical integration. We have elaborated the potential impact and implications of COTC on global petrochemical production.

Section 2 summarizes the overall PX production economics of Zhejiang Phase 1 refinery-PX complex. The economics are evaluated under a wide range of oil price scenarios and compared with Hengli’s project.

2021 marked the start of the central government’s latest effort to consolidate and tighten supervision over the refining sector and to cap China’s overall refining capacity.[14] Besides imposing a hefty tax on imports of blending fuels, Beijing has instituted stricter tax and environmental enforcement[15] measures including: performing refinery audits and inspections;[16] conducting investigations of alleged irregular activities such as tax evasion and illegal resale of crude oil imports;[17] and imposing tighter quotas for oil product exports as China’s decarbonization efforts advance.[18]

Yet, of the three most recent major additions to China’s greenfield refinery landscape, none are in Shandong province, home to a little over half the country’s independent refining capacity. Hengli’s Changxing integrated petrochemical complex is situated in Liaoning, Zhejiang’s (ZPC) Zhoushan facility in Zhejiang, and Shenghong’s Lianyungang plant in Jiangsu.[21]

As China’s independent oil refining hub, Shandong is the bellwether for the rationalization of the country’s refinery sector. Over the years, Shandong’s teapots benefited from favorable policies such as access to cheap land and support from a local government that grew reliant on the industry for jobs and contributions to economic growth.[22] For this reason, Shandong officials had resisted strictly implementing Beijing’s directives to cull teapot refiners and turned a blind eye to practices that ensured their survival.

In 2016, during the period of frenzied post-licensing crude oil importing by Chinese independents, Saudi Arabia began targeting teapots on the spot market, as did Kuwait. Iran also joined the fray, with the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) operating through an independent trader Trafigura to sell cargoes to Chinese independents.[27] Since then, the coming online of major new greenfield refineries such as Rongsheng ZPC and Hengli Changxing, and Shenghong, which are designed to operate using medium-sour crude, have led Middle East producers to pursue long-term supply contracts with private Chinese refiners. In 2021, the combined share of crude shipments from Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, and Kuwait to China’s independent refiners accounted for 32.5%, an increase of more than 8% over the previous year.[28] This is a trend that Beijing seems intent on supporting, as some bigger, more sophisticated private refiners whose business strategy aligns with President Xi’s vision have started to receive tax benefits or permissions to import larger volumes of crude directly from major producers such as Saudi Arabia.[29]

The shift in Saudi Aramco’s market strategy to focus on customer diversification has paid off in the form of valuable supply relationships with Chinese independents. And Aramco’s efforts to expand its presence in the Chinese refining market and lock in demand have dovetailed neatly with the development of China’s new greenfield refineries.[30] Over the past several years, Aramco has collaborated with both state-owned and independent refiners to develop integrated liquids-to-chemicals complexes in China. In 2018, following on the heels of an oil supply agreement, Aramco purchased a 9% stake in ZPC’s Zhoushan integrated refinery. In March of this year, Saudi Aramco and its joint venture partners, NORINCO Group and Panjin Sincen, made a final investment decision (FID) to develop a major liquids-to-chemicals facility in northeast China.[31] Also in March, Aramco and state-owned Sinopec agreed to conduct a feasibility study aimed at assessing capacity expansion of the Fujian Refining and Petrochemical Co. Ltd.’s integrated refining and chemical production complex.[32]

Meanwhile, though, enticed by discounted prices Chinese independents in Shandong province have continued to scoop up sanctioned Iranian oil, especially as their domestic refining margins have thinned due to tight regulatory scrutiny. In fact, throughout the period in which Iran has been under nuclear-related sanctions, Chinese teapots have been a key outlet for Iranian oil, which they reportedly unload from reflagged vessels representing themselves as selling oil from Oman and Malaysia.[38] China Concord Petroleum Company (CCPC), a Chinese logistics firm, remained a pivotal player in the supply of sanctioned oil from Iran, even after it was blacklisted by Washington in 2019.[39] Although Chinese state refiners shun Iranian oil, at least publicly, because of US sanctions, private refiners have never stopped buying Iranian crude.[40] And in recent months, teapots have been at the forefront of the Chinese surge in crude oil imports from Iran.[41]

Saudi Aramco today signed three Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) aimed at expanding its downstream presence in the Zhejiang province, one of the most developed regions in China. The company aims to acquire a 9% stake in Zhejiang Petrochemical’s 800,000 barrels per day integrated refinery and petrochemical complex, located in the city of Zhoushan.

The first agreement was signed with the Zhoushan government to acquire its 9% stake in the project. The second agreement was signed with Rongsheng Petrochemical, Juhua Group, and Tongkun Group, who are the other shareholders of Zhejiang Petrochemical. Saudi Aramco’s involvement in the project will come with a long-term crude supply agreement and the ability to utilize Zhejiang Petrochemical’s large crude oil storage facility to serve its customers in the Asian region.

Phase I of the project will include a newly built 400,000 barrels per day refinery with a 1.4 mmtpa ethylene cracker unit, and a 5.2 mmtpa Aromatics unit. Phase II will see a 400,000 barrels per day refinery expansion, which will include deeper chemical integration than Phase I.

Zhejiang Petroleum & Chemical Co Ltd, one of two new major refineries built in China in 2019, said it has started up the remaining units in the first phase of its refinery and petrochemical complex.

The company, 51% owned by private chemical group Zhejiang Rongsheng Holdings, said it has started test production at ethylene, aromatics and other downstream facilities, without giving further details.

Zhejiang Petrochemical started a first 200,000 barrels per day (bpd) crude processing unit in late May, following on from the start of a 400,000-bpd refinery owned by another private chemical major Hengli Petrochemical.

Plans for a joint Saudi Arabia-China refining and petrochemical complex to be built in northeast China that were shelved in 2020 are now being discussed again, according tosources close to the deal. The original deal for Saudi Aramco and China’s North Industries Group (Norinco) and Panjin Sincen Group to build the US$10 billion 300,000 barrels per day (bpd) integrated refining and petrochemical facility in Panjin city was signed in February 2019. However, in the aftermath of the enduring low prices and economic damage that hit Saudi Arabia as a result of the Second Oil Price War it instigated in the first half of 2020 against the U.S. shale oil threat, Aramco pulled out of the deal in August of that year.

The fact that this landmark refinery joint venture is back under serious consideration underlines the extremely significant shift in Saudi Arabia’s geopolitical alliances in the past few years – principally away from the U.S. and its allies and towards China and its allies. Up until the 2014-2016 Oil Price War, intended by Saudi Arabia to destroy the then-nascent U.S. shale oil sector, the foundation of U.S.-Saudi relations had been the deal struck on 14 February 1945 between the then-U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Saudi King Abdulaziz. In essence, but analyzed in-depth inmy new book on the global oil markets,this was that the U.S. would receive all of the oil supplies it needed for as long as Saudi had oil in place, in return for which the U.S. would guarantee the security both of the ruling House of Saud and, by extension, of Saudi Arabia.

After the end of the 2014-2016 Oil Price War, Saudi Arabia had not only lost the upper hand in global oil markets that it had established alongside other OPEC member states with the 1973 Oil Embargo but it had also prompted a catastrophic breach of trust with its former allies in Washington. Consequently, the U.S. changed the effective terms of 1945 to: the U.S. will safeguard the security both of Saudi Arabia and of the ruling House of Saud for as long as Saudi not only guarantees that the U.S. will receive all of the oil supplies it needs for as long as Saudi has oil in place but also that Saudi Arabia does not attempt to interfere with the growth andprosperity of the U.S. shale oil sector. Shortly after that (in May 2017), the U.S. assured the Saudis that it would protect them against any Iranian attacks, provided that Riyadh also bought US$110 billion of defense equipment from the U.S. immediately and another US$350 billion worth over the next 10 years. However, the Saudis then found out that none of these weapons were able to prevent Iran from launchingsuccessful attacksagainst its key oil facilities in September 2019, or several subsequent attacks.

Later, the first discussions about the joint Saudi-China refining and petrochemical complex in China’s northeast began, with a bonus for Saudi Arabia being that Aramco was intended to supply up to 70 percent of the crude feedstock for the complex that was to have commenced operation in 2024. This, in turn, was part of a multiple-deal series that also included three preliminary agreements to invest in Zhejiang province in eastern China. The first agreement was signed to acquire a 9 percent stake in the greenfield Zhejiang Petrochemical project, the second was a crude oil supply deal signed with Rongsheng Petrochemical, Juhua Group, and Tongkun Group, and the third was with Zhejiang Energy to build a large-scale retail fuel network over five years in Zhejiang province.

Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) has signed a broad framework agreement with China’s Rongsheng Petrochemical to explore domestic and international growth opportunities in support of ADNOC’s 2030 growth strategy.

The companies will examine opportunities in the sale of refined products from ADNOC to Rongsheng, downstream investment opportunities in both China and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the supply of liquified natural gas (LNG) to Rongsheng.

Under the terms of the deal, the companies will also study chances to increasing the volume and variety of refined product sales to Rongsheng as well as ADNOC’s participation as the China firm’s strategic partner in refinery and petrochemical projects. This could include an investment in Rongsheng’s downstream complex.

In return, Rongsheng will also look at investing in ADNOC’s downstream industrial ecosystem in Ruwais, UAE, including a proposed gasoline-to-aromatics plant as well as reviewing the potential for ADNOC to supply LNG to Rongsheng for use within its own complexes in China.

Rongsheng’s chairman Li Shuirong added that the cooperation will ensure that its project, which will have a refining capacity of up to 1 million bbl/day of crude oil, has adequate supplies of feedstock.

The Chinese group holds a 51% stake in Zhejiang Petroleum & Chemical Company (ZPC), which is currently building a major refining and petrochemical complex in Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, to comprise two oil refineries and two 1.4 million t/y ethylene plants. The first phase is due for completion in 2020. Saudi Aramco agreed in February 2019 to take over the Zhoushan government’s 9% share in the project.

Were the extra barrels needed to satisfy unusually strong refinery demand? A desire to stockpile supply for later consumption? Or perhaps add more cushion to strategic reserves?

It has also announced a plan to acquire a 9 percent stake in Zhejiang Petrochemical, an 800,000-bpd integrated refinery and petrochemical complex, controlled by private Chinese chemical group Zhejiang Rongsheng Holding Group.

According to Wang Lu, Asia-Pacific oil and gas analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, the start up of new refining and petrochemical plants in China will support oil import growth in the 2019 to 2021 period.

According to Nasser, while the company is a major market player in the upstream sector, with an average of 1.2 million bpd exported to China in 2018 and an expected 1.5 million bpd during the first quarter of 2019, the energy behemoth is looking at further strengthening its downstream presence in China.

China is the world’s most populous country (1.4 billion people in 2019) with a fast-growing economy that has led it to be the largest energy consumer and producer in the world.1 Rapidly increasing energy demand has made China influential in world energy markets. Despite structural changes to China’s economy during the past few years, China’s energy demand is expected to increase, and government policies support cleaner fuel use and energy efficiency measures.

China’s official data reported that its economy grew by 6.1% in 2019, which was the lowest annual growth rate since 1990. After registering an average growth rate of 10% per year between 2000 and 2011, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth has slowed or remained flat each year since then.2 The 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and resulting economic effects has adversely affected industrial and economic activity and energy use within China and are likely to push GDP growth much lower than 6% in 2020, according to numerous analysts.3

Coal supplied most (about 58%) of China’s total energy consumption in 2019, down from 59% in 2018. The second-largest fuel source was petroleum and other liquids, accounting for 20% of the country’s total energy consumption in 2019. Although China has diversified its energy supplies and cleaner burning fuels have replaced some coal and oil use in recent years, hydroelectric sources (8%), natural gas (8%), nuclear power (2%), and other renewables (nearly 5%) accounted for relatively small but growing shares of China’s energy consumption.4 The Chinese government intends to cap coal use to less than 58% of total primary energy consumption by 2020 in an effort to curtail heavy air pollution that has affected certain areas of the country in recent years. According to China’s estimates, coal accounted for a little less than 58% in 2019, which places the government within its goal.5 Natural gas, nuclear power, and renewable energy consumption have increased during the past few years to offset the drop in coal use.6 (Figure 1)

Although China was the fifth-largest petroleum and other liquids producer in the world in 2019, most of the country’s production comes from legacy fields that require expensive enhanced oil recovery techniques to sustain production. After declining considerably for three years, China’s petroleum and other liquids production reversed course and increased to 4.9 million barrels per day (b/d) in 2019 (Figure 2). Nearly 80% of the total liquids production was from crude oil, and the remainder was from conversions of coal and methanol to liquids, biofuels, and refinery processing gains.

Oil production from coal-to-liquids (CTL) plants was an estimated 108,000 b/d and from methanol-to-liquids was around 500,000 b/d in 2019.7 China is attempting to monetize its vast coal reserves by converting some of it to cleaner-burning fuels and using them for bolstering energy security in the petroleum sector. At the end of 2016, Shenhua Group brought online the world’s largest CTL plant, Ningxia, with a capacity to produce more than 80,000 b/d of oil.8 China’s CTL plant capacity could triple in size between 2017 and 2023, barring project delays.9 Most of China’s methanol is sourced from coal, and the government is encouraging more conversion of methanol to fuel and petrochemicals.

In response to China’s growing use of imported crude oil, the government called for the national oil companies (NOCs) to raise domestic oil production levels in 2018. The oil price recovery starting in 2016 also made developing China’s technically challenging fields profitable. These factors prompted the three major NOCs to increase joint upstream investment by 30% in 2018 and 23% in 2019.10

China’s oil consumption growth accounted for an estimated two-thirds of incremental global oil consumption in 2019. China consumed an estimated 14.5 million b/d of petroleum and other liquids in 2019, up 500,000 b/d, or nearly 4%, from 201814 (Figure 2).

The warmer-than-normal 2019–20 winter in the northern hemisphere and ongoing efforts to prevent the spread of COVID-19 is expected to drastically lower China’s growth in petroleum products, primarily jet fuel, gasoline, and diesel, with the most acute demand destruction occurring during the first quarter of 2020.

Diesel and gasoline accounted for the largest shares (27% and 24%, respectively, in 2018) of consumed oil products during the past several years. However, the pace of oil demand growth in the transportation sector has declined in the past few years because of China’s economic slowdown, stricter environmental measures resulting in higher fuel efficiency standards and restrictions on urban vehicle use, and a higher penetration of alternative fuel vehicles (electric vehicles, compressed natural gas vehicles, and trucks and trains running on liquefied natural gas). Alternative fuel vehicles have grown exponentially in China and have displaced a growing amount of gasoline and diesel each year.15 However, the sale of vehicles that run on alternative fuels fell slightly in 2019 from 2018 following China’s subsidy cut for these vehicles in July 2019.16 China, which has some of the most stringent global fuel standards, implemented national fuel standards equivalent to Euro VI to lower sulfur standards in gasoline and diesel starting in 2020 17

China has steadily expanded its oil refining capacity during the past decade to meet its strong demand growth and to process a wider range of crude oil types. China’s installed crude oil refining capacity reached about 17 million b/d by the end of 2019 and ranks second behind the United States’ capacity globally.19

The new capacity that began coming online in 2019 is from the first large integrated refinery complexes that are linked to petrochemical facilities. These refineries are primarily intended to produce naphtha for the petrochemical plants. The 400,000 b/d Hengli refinery began operations in mid-2019, and Zhejiang’s Rongsheng facility, with 400,000 b/d of capacity, brought online all of the first phase units by the end of 2019.20 Sinopec and Kuwait Petroleum are constructing a 200,000 b/d integrated refinery in Zhanjiang, coming online by 2021. A second phase of Zhejiang’s Rongsheng plant and the 320,000 b/d Shenghong Petrochemical refinery are slated to be online by the mid-2020s, and several other large refineries are in various stages of planning.21

Even though China releases limited information on its crude oil inventories and stockbuilding progress, industry analysts assess that Beijing has been swiftly filling its strategic petroleum reserves (SPR) since 2016. Industry trade press estimates that China has more than 300 million barrels of crude oil stored in at least 12 SPR facilities. In addition, China has a sizeable amount of commercial storage capacity that houses some of the country’s strategic reserves, which industry analysts estimated up to 600 million barrels in 2019.22

In September 2019, China announced that the country had 80 days of crude oil inventories to cover its imports, which is close to China’s goal for its SPR program of 90 days of import cover.23 Despite closing the gap on its target inventories, China has plans to begin building the third phase of its SPR program in the next few years.24 Industry analysts suggest that China continued to build its oil storage reserves through the first half of 2020 to take advantage of the low international oil prices. Crude oil imports remained higher than the levels from the previous year while oil demand declined significantly.25

As China’s oil demand continues to outstrip domestic production and the country continues building its strategic petroleum reserves, oil imports have greatly increased during the past decade, reaching record highs in 2019. To ensure adequate oil supply and mitigate geopolitical uncertainties, China has diversified its sources of crude oil imports in recent years. China, which became the world’s largest crude oil buyer in 2017, imported 10.1 million b/d of crude oil on average in 2019, rising almost 10% from 9.2 million b/d in 2018.26

Saudi Arabia, which historically has exported a significant portion of China’s crude oil, was the largest source of imports in 2019, with a 16% share.27 Saudi Aramco signed more long-term crude oil supply agreements with Chinese companies in early 2019 as the company focused on supplying China’s new refineries and petrochemical plants.28

After being China’s top source of crude oil imports for three years, Russia returned to being China’s second-largest source of crude oil imports in 2019 (Figure 3). Crude oil exports from Russia to China began to increase following new upstream production from Eastern Siberian fields, construction of pipeline and transmission infrastructure between the countries, and China’s lifting of a crude oil import ban on its independent oil refineries in the country’s northeastern region in 2015.

Sanctions on Iran’s crude oil and condensate exports by the United States have significantly reduced China’s intake of oil from Iran, particularly in the latter half of 2018 and in 2019. Oil from Iran fell to 3% of China’s imports in 2019 compared with 8% in 2016, according to China’s official import data.29 China reported that oil imports from Iran fell to about 100,000 b/d at the end of 2019, although it may have additional volumes imported as bonded storage that have not yet cleared customs. Saudi Arabia offset most of this loss.30

Crude oil imports from the United States declined significantly from the 2018 level of 231,000 b/d.32 China imposed a 5% tariff on U.S. crude oil imports in September 2019, which reduced oil imports from the United States by 48% in 2019. After signing the first phase of a trade deal with the United States in January 2020, China reduced the tariff on U.S. crude oil imports to 2.5% starting in February 2020. China’s government also began to offer tariff exemptions on crude oil from the United States so that China can meet its agreement to purchase $52 billion of additional U.S. energy products through 2021.33

China’s natural gas production has been steadily rising during the past several years as the country tries to fill the growing need for natural gas. China’s NOCs produced an estimated 6.3 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas in 2019, 8% higher than in 2018 (Figure 4).34 Although still in its early phase of development, China’s shale gas production rose substantially by 14% from 2017 levels to about 365 billion cubic feet (Bcf) in 2018.35

China’s offshore natural gas production increased 10.5% from 2018 to 335 Bcf in 2019, mostly from growth in the South China Sea.37 CNOOC, China’s major offshore producer, plans to commission the country’s second deepwater natural gas field, Lingshui 17-2, and the newly explored large Bozhong 19-4 natural gas and condensate field in the Bohai Bay in northeastern China by 2022.38

China’s government anticipates boosting the share of natural gas as part of total energy consumption from almost 8% in 2019 to 10% by 2020 and 14% by 2030 to alleviate the elevated levels of pollution resulting from the country’s heavy coal use.39 Although natural gas is still a small contributor to China’s overall energy portfolio, it is swiftly becoming an important fuel source, and China is now one of the fastest-growing natural gas markets in the world.

China’s natural gas consumption rose by 9% in 2019 to 10.8 Tcf from 9.9 Tcf in 2018.40 During the past decade, China’s natural gas demand increased rapidly by about 13% per year, making it the world’s third-largest natural gas consumer behind the United States and Russia (Figure 4).41 Although most natural gas consumption comes from industrial users, including mining and oil and natural gas extraction (accounting for more than 40% in 2018), the shares of natural gas consumption in the electric power and transportation sectors have risen during the past decade.42

China relaxed its coal-to-gas switching program at the end of 2018 to alleviate natural gas shortages that occurred in the winter of 2017–18, particularly in northern cities. This policy shift and slower economic growth caused the pace of China’s natural gas demand growth in 2019 to decelerate from significantly higher growth in 2017 and 2018.44

To fill the widening gap between China’s domestic natural gas production and demand, the industry has relied on an increasing amount of pipeline imports and liquefied natural gas (LNG) trade. In 2019, China, the largest natural gas importer in the world, imported 4.6 Tcf, 7% higher than 2018 levels. LNG imports account for 62% of the total, and pipeline imports, mostly from Turkmenistan, account for 38% (Figure 5).46

China surpassed South Korea and became the second-largest LNG importer after Japan in 2017. LNG imports climbed to 2.9 Tcf in 2019, rising 13% from 2018 levels. LNG imports have sharply accelerated each year since 2015 as a result of lower global LNG prices and China’s coal-to-gas switching policies.47 As a result of the economic and energy consumption slowdown in the first few months of 2020 in response to COVID-19 containment efforts, some Chinese NOCs have declared force majeure on some contract cargoes or have delayed receipts because natural gas demand has contracted. The macroeconomic effects from the pandemic response will likely dampen China’s LNG growth in 2020.48

China has diversified its LNG suppliers during the past few years, and Australia is now the largest supplier, at 46% in 2019. Purchases from new natural gas liquefaction projects in Australia began in 2016. LNG imports from the United States grew rapidly in 2017 and 2018, reaching an average of 5% of China’s total LNG imports. However, U.S. imports slowed significantly after September 2018 when China imposed a 10% tariff on U.S. LNG shipments as part of the trade dispute between the two countries. China raised LNG tariffs on the United States to 25% in June 2019, and LNG imports from the United States dropped to zero by April 2019.49 After signing the first phase of a trade deal with the United States in January 2020, China’s government offered tariff exemptions on LNG from the United States, which could bolster U.S. LNG cargoes to China for the first time in more than a year.50

As of late 2019, China had 21 LNG regasification terminals with a combined capacity of 3.5 Tcf. China is quickly building various terminals along its entire coastline, and another 1.9 Tcf is under construction and slated to come online by 2023.51

China’s rapidly growing natural gas demand during the past few years has opened up opportunities for independent or non-NOC Chinese energy companies to operate in the LNG space. Several local state-owned municipalities, natural gas distributors, and power developers own stakes in existing LNG terminals. In 2019, the government renewed an initiative in 2014 to allow access rights to third-party companies for supplying natural gas to LNG terminals, providing more supply opportunities for firms involved along the entire LNG supply chain, from the upstream natural gas procurement to the downstream distribution. CNOOC has signed several LNG third-party access deals with various independent companies since late 2018, and it released third-party access bids on the Shanghai Petroleum and Gas Exchange in early 2019.52

Natural gas pipeline imports fell slightly in 2019 to 1.7 Tcf, most of which are from Turkmenistan.53 In addition to the natural gas pipeline imports from Central Asia and Burma, China began importing natural gas from Russia through the Power of Siberia pipeline in December 2019. China and Russia signed a natural gas deal in 2014 in which China will import an average of 1.3 Tcf per year of natural gas from Gazprom’s East Siberian fields during a 30-year period. Russia expects to ramp up supplies during the next few years and send 530 million cubic feet by 2022. Russia’s portion of the pipeline project to the Chinese border came online at the end of 2019. China plans to expand its side of the pipeline, which will deliver natural gas to Beijing and other demand centers, in late 2020.54 This new supply of natural gas from Russia will compete with the LNG imports into northern China and diversify China’s natural gas supply.

China’s domestic pipeline infrastructure is undergoing significant development, and the government’s goals are to increase the country’s natural gas pipeline coverage and to improve market competition along the value chain of natural gas sales. The government created a national oil and natural gas pipeline company, PipeChina, in December 2019. In the next few years, China is set to separate the NOCs’ upstream, midstream, and downstream pipeline sectors and allow open access to companies on the national pipeline. In addition, in 2019, China began to allow foreign companies to invest in city natural gas distribution pipelines to facilitate greater investment levels and faster infrastructure development.57

After several years of declines, China’s coal consumption grew by 1% each year in 2018 and 2019, based on physical volume (more than 4.3 billion short tons in 2019), according to estimates of China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (Figure 6).58 Electricity and industrial demand growth, especially from steel production, were strong.59 In addition, some provincial governments eased air quality measures starting in the winter of 2018–19 as a result of natural gas supply shortages and high natural gas prices during peak energy demand periods in 2017.60

Coal production, which declined for three consecutive years through 2016, has risen each year since then and reached an estimated 4.1 billion short tons in 2019 (Figure 6).62 China’s government adopted a supply-side approach to control the volatility of domestic coal prices through a targeted price range, which allowed domestic producers to be profitable and compete with coal imports.

Because coal demand from the power sector and coal prices began rising at the end of 2016, China relaxed several policies that restricted domestic coal production. China raised production capacity and began to replace uncompetitive and outdated mine capacity. Output growth was from the largest coal-producing mines in the north central and northwestern areas of the country. China continues to replace outdated coal capacity with new, more efficient mine capacity and to close smaller mines in the eastern and southern regions.63 Furthermore, China’s recent expansion of long-range railway capacity, such as the Haoji Railway commissioned in October 2019, to connect the coal-producing centers in the interior to eastern demand centers is instrumental to bolstering domestic production and responding to coal demand.64

China’s coal imports, the largest in the world, rose from 2015 levels of 225 million short tons (MMst) to about 330 MMst in 2019.65 After China cut domestic coal production capacity in 2016, markets along the southeastern coasts tightened and domestic prices rose substantially, leading to a recovery in coal imports. However, after 2016, imports increased at a slower pace. China has controlled coal import levels during the past few years to aid domestic producers by leveraging import quotas or setting restrictions at various ports. Therefore, imports are determined by both market fundamentals and policy initiatives.66

Indonesia remains China’s largest source of imported coal with a 46% share. Indonesia offers a low quality coal that blends well with China’s domestic coal.67 Australia ranks as the second-largest coal exporter to China with a 26% share and is a major supplier of metallurgical coal primarily used for steel production. Neighboring countries Mongolia and Russia have significantly increased their shares of coal exports to China during the last few years, accounting for 12% and 11% of imports, respectively, in 2019.68

China generated about 6,712 terawatthours (TWh) of net electricity in 2018, an increase of more than 7% from 2017.69 Higher generation growth was strengthened by a return to growth in the industrial sector and strong growth in the service and residential sectors. Higher use of technology in manufacturing and other sectors is a significant driver of electricity demand. In addition, infrastructure expansion bolstered electricity demand in the steel and cement sectors. More transitions from coal to electricity for residential and commercial heating purposes is contributing to a smaller portion of the power demand growth.70 Estimates by the Chinese government report that power generation rose by about 5% in 2019. The economic slowdown during late 2018 and 2019 reduced electricity demand.71 Further erosion of electricity demand growth is set to occur in 2020 as a result of the effects of COVID-19 containment measures on China’s economy and industrial output.72

In response to stakeholder feedback, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) has revised the format of the Country Analysis Briefs. As of September 2019, updated briefs are available in two complementary formats: the Country Analysis Executive Summary provides an overview of recent developments in a country’s energy sector, and the Background Reference provides historical context. The Background Reference for China is forthcoming. Archived versions will remain available in the original format.

China Daily, “China to cap coal consumption at 4.1 billion tons by 2020,” January 18, 2017; Reuters, “Coal’s share of China energy mix falls to 57.7% in 2019 – stats bureau,” February 27, 2020; China’s National Bureau of Statistics, “Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2019 National Economic and Social Development,” February 28, 2020; BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020.

International Energy Agency, Oil Market Report, April 15, 2020, page 24 and Oil Market Report, April 11, 2019, page 24; Reuters; International Energy Agency, Oil 2020: Analysis and Forecast to 2025, page 66; Reuters, “Drill, China, drill: State majors step on the gas after Xi calls for energy security,” February 1, 2019.

FACTS Global Energy, Asia Pacific Petroleum Databook 1: Supply and Demand, Spring 2019, pages 27-29; International Energy Agency, Oil 2020, pages 29-30 and 34; International Energy Agency, Oil 2019, pages 35-38.

International Energy Agency, Oil 2020, page 29; The International Council on Clean Transportation, “China’s Stage VI emissions standard for heavy-duty vehicles (final rule),” July 20, 2018; Xinhua News, “China Focus: China starts implementing tougher vehicle emission standards,” July 2, 2019; Dieselnet, China: Cars and Light Trucks; International Energy Agency, Oil Market Report, November 15, 2019, page 12.

FACTS Global Energy, Asia-Pacific Databook 2: Refining Configuration and Construction, Fall 2019, pages 21-25; International Energy Agency, Oil 2020, pages 95, 113.

The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, “US-China: The Great Decoupling,” July 2019, page 8; Newsbase AsianOil, “China’s Imports Continue to Rise,” April 16, 2020, page 9; S&P Global Platts, “Analysis: China puts Iranian crude into strategic petroleum reserves in June,” July 30, 2019; FACTS Global Energy, China Oil Monthly, January 21, 2020, page 3; FACTS Global Energy, Energy Insights, “China’s Crude Storage: Is Enough Ever Really Enough?,” January 22, 2019; China’s National Bureau of Statistics, “Significant progress has been made in the construction of national oil reserves,” December 29, 2017; Reuters, “UPDATE 2-China accelerates stockpiling of state oil reserves over 2016/17,” December 29, 2017; Reuters, “China’s crude oil buying spree looks set to continue – IEA,” October 12, 2017.

Reuters, “Saudi Arabia to boost oil exports to China with strategy shift,” February 26, 2019; Middle East Economic Survey, “China Takes Record Saudi Crude As Iran Volumes Fall to 9-Year Low,” August 2, 2019, pages 8-9.

FACTS Global Energy, China Oil Monthly Data Tables, February 2020, page 2; Middle East Economic Survey, “China Takes Record Saudi Crude As Iran Volumes Fall to 9-Year Low,” August 2, 2019, pages 8-9.

FACTS Global Energy, East of Suez Gas Databook 2019, China Natural Gas Outlook, September 2019, page 21; FACTS Global Energy, China Gas Monthly, March 2019, page 4.

International Energy Agency, Gas Market Report 2019, page 20; The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, “The Outlook for Natural Gas and LNG in China in the War Against Air Pollution,” December 2018, page 33; FACTS Global Energy, East of Suez Gas Databook: China Natural Gas Outlook, September 2019, page 17.

FACTS Global Energy, China Gas Monthly, March 18, 2020, pages 3-4; S&P Global Platts, “China’s Jan-Feb natural gas import growth slows to 2.8% in 2020 from 18.5% in 2019,” March 7, 2020.

FACTS Global Energy, China Gas Monthly, June 18, 2019, pages 3-4; S&P Global Platts, “CNOOC kick-starts China’s first long-term LNG terminal access,” March 13, 2019.

FACTS Global Energy, East of Suez Gas Databook 2019, China Natural Gas Outlook, September 2019, page 23; International Energy Agency, Gas Market Report 2019, page 120; Reuters, “China imports 840 mln cubic meters of Siberian natgas since pipeline launch,” February 26, 2020.

International Energy Agency, Gas Market Report 2019, page 120; FACTS Global Energy, “Gas/LNG Alert, “Slowdown in China LNG Demand Growth over 2019-2021 Amid Tepid GDP Growth and New Pipeline Gas Start-up,” March 1, 2019; Eurasianet, “Tajikistan Resumes Building Turkmenistan-China Pipeline Tajikistan Resumes Building Turkmenistan-China Pipeline,” January 31, 2018; Radio Free Europe, “Tajik Claim Of Pipeline Progress Is Welcome News In Turkmenistan,” January 31, 2020.

International Energy Agency, Gas Market Report 2019, page 119; FACTS Global Energy, “Gas/LNG Alert, “Slowdown in China LNG Demand Growth over 2019-2021 Amid Tepid GDP Growth and New Pipeline Gas Start-up,” March 1, 2019.

FACTS Global Energy, East of Suez Gas Databook 2019, China Natural Gas Outlook, September 2019, page 14; FACTS Global Energy, China Gas Monthly, December 2019, page 3; Reuters, “China sets up state oil, gas pipe firm to boost competition: Xinhua,” December 8, 2019; China Daily, “Foreign investment welcomed in gas and heating network,” July 9, 2019.

U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates using growth rates from National Bureau of Statistics of China, “Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2018 National Economic and Social Development,” February 28, 2019.

Reuters, “China boosts coal mining capacity despite climate pledges,” March 26, 2019; International Energy Agency, Coal 2019, pages 32-33; International Energy Agency, Coal 2018ss, pages 32-33.

International Energy Agency, Coal 2019, pages 31, 110, 123-124; Xinhua News, “Haoji Railway for coal transportation opens to traffic,” September 29, 2019.

China Daily, “Power market tipped for record 2018,” January 11, 2019; International Energy Agency, Coal 2018, page 19 and Coal 2019, page 16; Reuters, “China’s 2018 coal usage rises 1 percent, but share of energy mix falls,” February 27, 2019; Reuters, “Chinese power consumption climbed over 6 percent in 2017: NEA” January 21, 2018.

National Bureau of Statistics of China, “Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2019 National Economic and Social Development” February 28, 2020; National Bureau of Statistics, National Data (accessed April 2020); Xinhua News, “China’s power use up 4.5 pct in 2019,” January 25, 2020.

International Energy Agency, Gas Market Report 2019, page 20; China Daily, “China to cap coal consumption at 4.1 billion tons by 2020,” January 18, 2017.

U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates; National Bureau of Statistics of China, “Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2018 National Economic and Social Development,” February 28, 2019.

8613371530291

8613371530291