saudi aramco rongsheng in stock

Saudi Aramco today signed three Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) aimed at expanding its downstream presence in the Zhejiang province, one of the most developed regions in China. The company aims to acquire a 9% stake in Zhejiang Petrochemical’s 800,000 barrels per day integrated refinery and petrochemical complex, located in the city of Zhoushan.

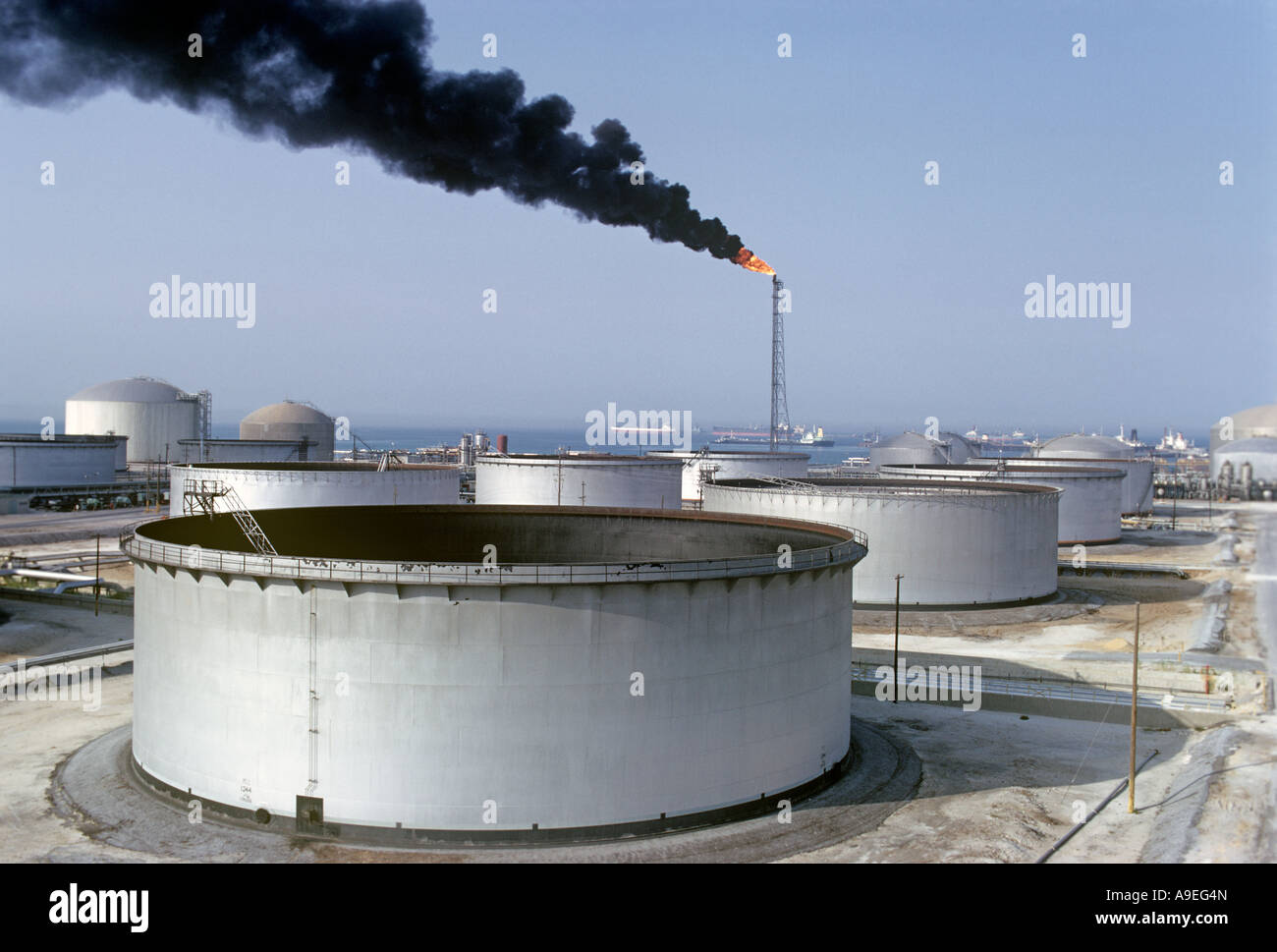

The first agreement was signed with the Zhoushan government to acquire its 9% stake in the project. The second agreement was signed with Rongsheng Petrochemical, Juhua Group, and Tongkun Group, who are the other shareholders of Zhejiang Petrochemical. Saudi Aramco’s involvement in the project will come with a long-term crude supply agreement and the ability to utilize Zhejiang Petrochemical’s large crude oil storage facility to serve its customers in the Asian region.

Saudi Aramco CEO, Amin Nasser said: “The agreements demonstrate our commitment to the Chinese market and help enhance the strategic integration of our downstream network in Asia. They will further strengthen our relationship with China and the Zhejiang province, setting the stage for more cooperation in the future.”

State oil giant Saudi Aramco plans to ink an agreement later on Thursday to take a stake in a refinery-petrochemical project in eastern China, a senior official said on Thursday.

"We will have a signing ceremony later today with the Zhejiang government to invest in the Zhejiang refinery-petrochemical project," Aramco"s Senior Vice President of Downstream, Abdulaziz al-Judaimi told an industry event.

Zhejiang Petrochemical, 51 percent owned by textile giant Rongsheng Holding Group, plans to start its 400,000-barrels-per-day refinery-petrochemical project in eastern China in late 2018.

SINGAPORE/DUBAI/BEIJING, Feb 21 (Reuters) - Saudi Aramco plans to sign preliminary deals to invest in two oil refining and petrochemical complexes in China during Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s state visit to Beijing this week, according to sources familiar with the plans.

Saudi Aramco, the world’s top oil exporter, will sign a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to build a refinery and petrochemical project in the northeastern Chinese province of Liaoning in a joint venture with China’s defence conglomerate Norinco, said three sources with knowledge of the matter.

Aramco is also expected to formalise an earlier plan to take a minority stake in Zhejiang Petrochemical, controlled by private Chinese chemical group Zhejiang Rongsheng Holding Group , said two sources with knowledge of this particular deal. Zhejiang Petrochemical is building a refinery and petrochemical complex in eastern Chinese province of Zhejiang.

The investments could help Saudi Arabia regain its place as the top oil exporter to China, which it has relinquished to Russia for the past three years. Saudi Aramco is poised to bolster its market share by signing supply agreements with non-state Chinese refiners.

It is not clear what new details will be in the MOU with Norinco expected during the visit, as the two companies first announced an alliance in May 2017 during Saudi ruler King Salman’s visit to Beijing.

A senior Aramco executive said last June he expected the front-end engineering for the Norinco project to be finished by mid-2019, following which the company will take a final investment decision.

The agreement follows an earlier MOU that Aramco signed in October to invest in Zhejiang’s project, which is planned as a refinery to process 400,000 bpd of crude and associated petrochemical facilities in the city of Zhoushan, south of Shanghai.

The Saudi delegation, including top executives from Aramco, arrived in Beijing on Thursday for a two-day visit, part of the crown prince’s Asia tour, during which the kingdom has pledged $20 billion of investment in Pakistan and sought additional investment in India’s refining industry.

ZHOUSHAN, China (Reuters) - State oil giant Saudi Aramco (IPO-ARMO.SE) plans to ink an agreement later on Thursday to take a stake in a refinery-petrochemical project in eastern China, a senior official said on Thursday.

"We will have a signing ceremony later today with the Zhejiang government to invest in the Zhejiang refinery-petrochemical project," Aramco"s Senior Vice President of Downstream, Abdulaziz al-Judaimi told an industry event.

Zhejiang Petrochemical, 51 percent owned by textile giant Rongsheng Holding Group, plans to start its 400,000-barrels-per-day refinery-petrochemical project in eastern China in late 2018.

ZHOUSHAN, China/SINGAPORE (Reuters) - State oil giant Saudi Aramco signed an agreement on Thursday to invest in a refinery-petrochemical project in eastern China, part of its strategy to expand in downstream operations globally.

Zhejiang Petrochemical, 51 percent owned by textile giant Zhejiang Rongsheng Holding Group, is building a 400,000-barrels-per-day refinery and associated petrochemical facilities that was expected to start operations by the end of this year.

This is the third such project in China that Saudi Aramco has set its sight on as it seeks to lock in long-term outlets for its crude oil and produce fuel and petrochemicals to meet rising demand in Asia and cushion the risk of a slowdown in oil consumption.

The oil giant had not yet finalised the size of its stake in the project and still needed to complete due diligence, Aramco"s Senior Vice President of Downstream, Abdulaziz al-Judaimi, told Reuters on the sidelines of the event.

Aramco also owns part of the Fujian refinery-petrochemical plant with Sinopec and Exxon Mobil Corp, and has plans to build a 300,000-bpd refinery with China"s Norinco. It is also in talks with PetroChina to invest in a refinery in Yunnan.

Saudi Aramco signed three Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) on Friday to purchase a 9 percent stake in Chinese Zhejiang Petrochemical"s integrated refinery and petrochemical complex in the city of Zhoushan, and to invest in a retail fuel network in the eastern region of China, the Saudi state-run energy giant announced.

Saudi Aramco"s involvement in the project will come with a long-term crude supply agreement and the ability to utilize Zhejiang Petrochemical"s large crude oil storage facility to serve its customers in the Asian region, according to the statement.

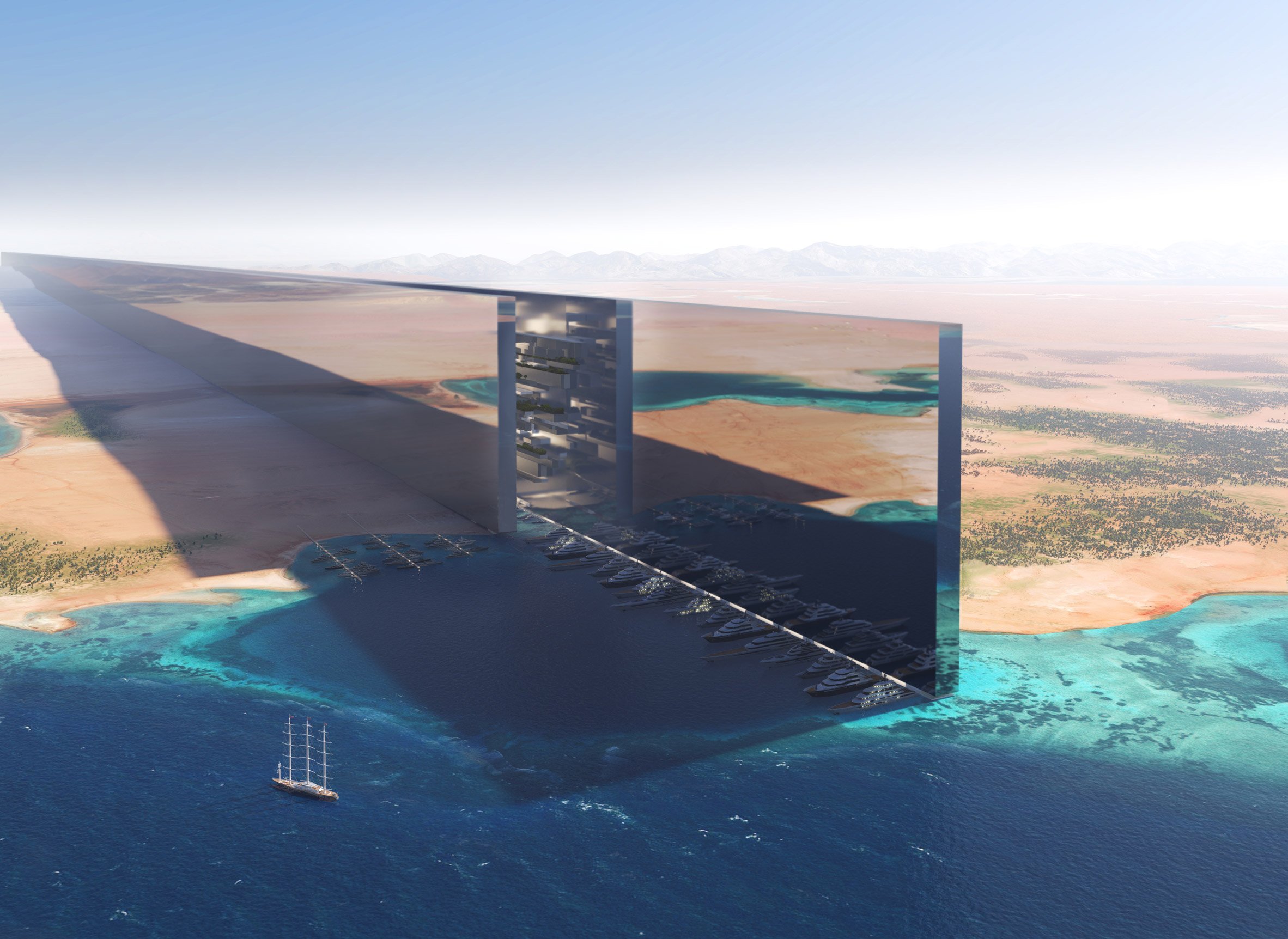

Saudi Aramco and Zhejiang Energy plan to build a large-scale retail network over the course of the next five years in the province, the statement added. The retail business will be integrated with the Zhejiang Petrochemical complex as an outlet for the facility"s refined products.

Saudi Aramco CEO Amin Nasser said the agreements demonstrate the company"s commitment to the Chinese market and would help enhance the strategic integration of its downstream network in Asia.

Saudi Arabian Oil Company (Saudi Aramco), one of the world"s top oil exporters, will continue to boost its downstream presence in China, after it formalized plans to build a 300,000-barrel-per-day refining and petrochemical complex along with Norinco Group and Panjin Sincen in Panjin, Northeast China"s Liaoning province, in February.

"This is a clear demonstration of Saudi Aramco"s strategy to move beyond a buyer-seller relationship to one where we can make significant investments to contribute to China"s economic growth and development," said Amin H. Nasser, president and CEO of Saudi Aramco.

It has also announced a plan to acquire a 9 percent stake in Zhejiang Petrochemical, an 800,000-bpd integrated refinery and petrochemical complex, controlled by private Chinese chemical group Zhejiang Rongsheng Holding Group.

The projects in Liaoning and Zhejiang have the potential to increase Saudi Aramco"s participated refining capacity to over 1 million bpd in China alone.

Figures from Bloomberg Intelligence reveal that Russia surpassed Saudi Arabia to become the largest crude oil exporter to China in 2016. Last year, China imported 71.49 million metric tons of oil from Russia while imports from Saudi Arabia were 56.73 million tons.

China is a strategic partner for Saudi Aramco and one of the most important customers globally, and the company is looking at both the export of oil and integration down the value chain in the Chinese market, he said.

"Integration with refining is what Saudi Aramco and our partners are looking at, and these opportunities will help to expand our presence in China, achieving a better balance between our upstream and downstream business segments, considering how much we export to China," said Nasser.

Nasser said the potential acquisition of petrochemical maker Saudi Basic Industries Corp, or SABIC, would also help the company strengthen its downstream sector in China.

Saudi Aramco aims to buy a controlling stake in SABIC, possibly the entire 70 percent owned by the Public Investment Fund - the kingdom"s top sovereign wealth fund.

"Part of the company"s strategy is to allocate 2 to 3 million bpd of crude to petrochemicals and expand our chemicals business globally," Nasser said. "China"s demand growth offers exciting opportunities for Saudi Aramco and its partners."

Plans for a joint Saudi Arabia-China refining and petrochemical complex to be built in northeast China that were shelved in 2020 are now being discussed again, according tosources close to the deal. The original deal for Saudi Aramco and China’s North Industries Group (Norinco) and Panjin Sincen Group to build the US$10 billion 300,000 barrels per day (bpd) integrated refining and petrochemical facility in Panjin city was signed in February 2019. However, in the aftermath of the enduring low prices and economic damage that hit Saudi Arabia as a result of the Second Oil Price War it instigated in the first half of 2020 against the U.S. shale oil threat, Aramco pulled out of the deal in August of that year.

The fact that this landmark refinery joint venture is back under serious consideration underlines the extremely significant shift in Saudi Arabia’s geopolitical alliances in the past few years – principally away from the U.S. and its allies and towards China and its allies. Up until the 2014-2016 Oil Price War, intended by Saudi Arabia to destroy the then-nascent U.S. shale oil sector, the foundation of U.S.-Saudi relations had been the deal struck on 14 February 1945 between the then-U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Saudi King Abdulaziz. In essence, but analyzed in-depth inmy new book on the global oil markets,this was that the U.S. would receive all of the oil supplies it needed for as long as Saudi had oil in place, in return for which the U.S. would guarantee the security both of the ruling House of Saud and, by extension, of Saudi Arabia.

After the end of the 2014-2016 Oil Price War, Saudi Arabia had not only lost the upper hand in global oil markets that it had established alongside other OPEC member states with the 1973 Oil Embargo but it had also prompted a catastrophic breach of trust with its former allies in Washington. Consequently, the U.S. changed the effective terms of 1945 to: the U.S. will safeguard the security both of Saudi Arabia and of the ruling House of Saud for as long as Saudi not only guarantees that the U.S. will receive all of the oil supplies it needs for as long as Saudi has oil in place but also that Saudi Arabia does not attempt to interfere with the growth andprosperity of the U.S. shale oil sector. Shortly after that (in May 2017), the U.S. assured the Saudis that it would protect them against any Iranian attacks, provided that Riyadh also bought US$110 billion of defense equipment from the U.S. immediately and another US$350 billion worth over the next 10 years. However, the Saudis then found out that none of these weapons were able to prevent Iran from launchingsuccessful attacksagainst its key oil facilities in September 2019, or several subsequent attacks.

Concomitant with this weakening of relations between Saudi Arabia and the U.S. came a drift towards Russia first and then China. Given the reputational damage done to the perceived power of Saudi Arabia and its OPEC brothers by their inability to destroy or disable the growing threat from U.S. shale oil to their former dominance in the global oil markets, their attempts to pull oil prices back up to levels at which they could begin to repair thedamage done to their economiesby the 2014-2016 Oil Price War towards the end of 2016 also failed. At that point, fully cognisant of the enormous economic and geopolitical possibilities that were available to it by becoming a core participant in the crude oil supply/demand/pricing matrix, Russia agreed to support the OPEC production cut deal in what was to be called from then-on ‘OPEC+’, albeit in its own uniquely self-serving and ruthless fashion, again analyzed in-depth inmy new book on the global oil markets.

Given Russia’s significant leverage in the Middle East by dint of its pivotal position in making the OPEC deal credible in terms of being able to affect global oil prices, China also began to more aggressively leverage its own power with the group and in the region by dint of its being the world’s biggest net importer of crude oil and its increasing use of checkbook diplomacy. Nowhere were the two elements more in evidence than in China’s offer to buy the entire 5 percent stake of Aramco in a private placement. This was designed to enable Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to save face, given hisunsuccessful attempts from 2016 to 2020to persuade serious Western investors to have any significant part in the company’s initial public offering. Shortly after the offer was made,China was referred toby Saudi’s then-vice minister of economy and planning, Mohammed al-Tuwaijri, as: “By far one of the top markets” to diversify the funding basis of Saudi Arabia. He added that: “We will also access other technical markets in terms of unique funding opportunities, private placements, panda bonds and others.” In a similar vein, andjust last year, Saudi Aramco’s chief executive officer, Amin Nasser, said: “Ensuring the continuing security of China’s energy needs remains our [Saudi Aramco’s] highest priority — not just for the next five years but for the next 50 and beyond.”

Between the end of the 2014-2016 Oil Price War and now, there have been multiple high-level visits back and forth between Saudi Arabia and China, beginning most notably with the trip of high-ranking politicians and financiers fromChina in August 2017 to Saudi Arabia, which featured a meeting between King Salman and Chinese Vice Premier, Zhang Gaoli, in Jeddah. During the visit, Saudi Arabia first mentioned seriously that it was willing to consider funding itself partly in Chinese yuan, raising the possibility of closer financial ties between the two countries. At these meetings, according to comments at the time from then-Saudi Energy Minister, Khalid al-Falih, it was also decided that Saudi Arabia and China would establish a US$20 billion investment fund on a 50:50 basis that would invest in sectors such as infrastructure, energy, mining, and materials, among other areas. The Jeddah meetings in August 2017 followed a landmark visit to China by Saudi Arabia’s King Salman in March of that year during which around US$65 billion of business deals were signed in sectors including oil refining, petrochemicals, light manufacturing, and electronics.

Later, the first discussions about the joint Saudi-China refining and petrochemical complex in China’s northeast began, with a bonus for Saudi Arabia being that Aramco was intended to supply up to 70 percent of the crude feedstock for the complex that was to have commenced operation in 2024. This, in turn, was part of a multiple-deal series that also included three preliminary agreements to invest in Zhejiang province in eastern China. The first agreement was signed to acquire a 9 percent stake in the greenfield Zhejiang Petrochemical project, the second was a crude oil supply deal signed with Rongsheng Petrochemical, Juhua Group, and Tongkun Group, and the third was with Zhejiang Energy to build a large-scale retail fuel network over five years in Zhejiang province.

This latest Aramco-Norinco-Panjin Sincen deal, though, carries with it even broader ramifications of a much more overtly testing nature for U.S. President Joe Biden in terms of where he draws the line on supposed allies blurring trade considerations and security considerations. All Chinese companies function as part of the State apparatus – without any exception – and Norinco has the added troubling element for the U.S. that it is one of China’s major defense contractors, specializing in the full range of research, development, and production of military equipment, technology, systems, and weapons. This runs alongside ongoing concerns from Washington about Saudi Arabia’s on again-off again agreement with Russia tobuy its S-400 missile defense system, and much more recent news in December 2021 that Saudi Arabia is now actively manufacturing itsown ballistic missiles with the help of China.

The signing last week of a multi-pronged memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the Saudi Arabian Oil Company – formerly the Arabian American Oil Company - (Aramco) and the China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (Sinopec) is a critical step in China’s ongoing strategy to secure Saudi Arabia as a client state. As the president of Sinopec, Yu Baocai, himself put it: “The signing of the MoU introduces a new chapter of our partnership in the Kingdom…The two companies will join hands in renewing the vitality and scoring new progress of the Belt and Road Initiative [BRI] and [Saudi Arabia’s] Vision 2030.” The scale and scope of the MoU is enormous, covering deep and broad co-operation in refining and petrochemical integration, engineering, procurement and construction, oilfield services, upstream and downstream technologies, carbon capture and hydrogen processes. Crucially for China’s long-term plans in Saudi Arabia, it also covers opportunities for the construction of a huge manufacturing hub in King Salman Energy Park that will involve the ongoing, on-the-ground presence on Saudi Arabian soil of significant numbers of Chinese personnel: not just those directly related to the oil, gas, petrochemicals, and other hydrocarbons activities, but also a small army of security personnel to ensure the safety of China’s investments.

These developments are all in line with acomment made last March, at the annual China Development Forum hosted in Beijing, by Aramco chief executive officer, Amin Nasser: “Ensuring the continuing security of China’s energy needs remains our highest priority - not just for the next five years but for the next 50 and beyond.” At that point in early 2021, Aramco had a 25 percent stake in the 280,000 barrels per day (bpd) Fujian refinery in south China through a joint venture with Sinopec (and the U.S.’s ExxonMobil) and had also earlier agreed (in 2018) to buy a 9 percent stake in China’s 800,000 bpd ZPC refinery from Rongsheng. Several other joint projects between China and Saudi Arabia that had been agreed in principle were delayed due to a combination of the ongoing effects of Covid-19, Aramco’scrushing dividend repayment schedule, and concern from both countries – especially China – on how Washington might react to this clear threat to the U.S.’s own long-running interests in, and geopolitical relationship with, Saudi Arabia.

The basis of this enduring relationship between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, as analysed in depth inmy new book on the global oil markets, had been struck back in 1945 at a meeting on 14 February 1945 between the then-U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Saudi King at the time, Abdulaziz. The first face-to-face contact between the two, this landmark meeting was held on board the U.S. Navy cruiser Quincy in the Great Bitter Lake segment of the Suez Canal, and the deal that they agreed – which had been the basis for all of the U.S.’s Middle East policy up until very recently - was this: the U.S. would receive all of the oil supplies it needed for as long as Saudi had oil in place, in return for which the US would guarantee the security both of the ruling House of Saud and, by extension, of Saudi Arabia.

The landmark deal survived the 1973 Oil Crisis - in which the Saudi-led OPEC placed an embargo on oil exports to various countries that had continued to supply arms to Israel during the Yom Kippur War against it and a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria – although the U.S. had little choice but to do that, given the dearth of its own alternative oil supply options at that time. It also looked as though the deal might survive the Saudi-led Oil Price War from 2014 to 2016, aimed by Riyadh at destroying or at least severely disabling the then-nascent U.S. shale oil industry, although Washington would never trust the Saudis to the degree it had before the War again. The real death of the 1945 Bitter Lake deal came when Russia emerged at the end of 2016 to support the then-beleaguered Saudi Arabia and OPEC in future oil production deals, given the lack of credibility in the global oil markets that both had at the end of the 2014-2016 Oil Price War. Fully cognisant of the enormous economic and geopolitical possibilities that were available to it by becoming a core participant in the crude oil supply/demand/pricing matrix, as also detailed inmy new book on the global oil markets, Russia agreed to support the late-2016 OPEC production cut deal (in what was to be called from then-on ‘OPEC+’), although it did so in its own uniquely self-serving and ruthless fashion. At the end of 2016 at the latest, Washington knew its days of being able to count on Saudi Arabia in any meaningful way were over.

China usedRussia’s new leverage over Saudi Arabiaand OPECto deploy its own strategy to accrete and exploit power over the Middle East’s huge oil and gas reserves, with the key turning point for Beijing being its own rescue act for Saudi Arabia in the middle of 2017. As also analysed in depth inmy new book on the global oil markets, it was at that point that the then-newly appointed Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman (MbS), was facing a huge problem at a very vulnerable stage in his rise to power. His problem was twofold: first, he had portrayed himself to the senior Saudis whose support he desperately needed to stay in his new position as a man of canny international business and political instincts, and to this end he had promised them that he could float Saudi Aramco on international stock markets for a price that would value the whole company at US$2 trillion; second, international investors regarded the company as, in market parlance, a ‘dog with fleas’.

It was precisely when MbS was at his weakest that China stepped in and offered to buy the entire 5 percent stake in Aramco for a price that would guarantee the valuation for the whole company of the required US$2 trillion. Crucially as well, this would all be done through a private placement of the entire 5 percent share block in Aramco, which meant that none of the details surrounding the deal would ever get out publicly. As it transpired, several senior Saudis at the time - opponents to MbS’s ascension to power but still powerful voices in the Kingdom at that point – opposed the deal on the basis that it would make Saudi Arabia beholden to China. Although the deal did not go ahead, the subsequent trajectory of China-Saudi relations would suggest that MbS has never forgotten Beijing’s willingness to bail him out of any trouble in which he might find himself.

Saudi Arabia’s promise to ensure the continuing security of China’s energy needs remains its highest priority for the next 50 and beyond has found concrete expression since that assurance was made, most recently again with Aramco’s senior vice president downstream, Mohammed Y. Al Qahtani, announcing the creation of a“one stop shop”provided by his company in China’s Shandong. “The ongoing energy crisis, for example, is a direct result of fragile international transition plans which have arbitrarily ignored energy security and affordability for all,” he said. “The world needs clear-eyed thinking on such issues. That’s why we highly admire China’s 14th Five Year Plan for prioritising energy security and stability, acknowledging its crucial role in economic development,” he added. It has also found a broader expression in the news just before Christmas 2021 that U.S. intelligence agencies had found that Saudi Arabia is now manufacturing its ownballistic missiles with the help of China. Given China’s long-running and extensive ‘assistance’ to Iran’s nuclear ambitions, as analysed in full inmy latest book on the global oil markets,ongoing U.S. fears about what Beijing’s endgame might be in building out the nuclear capabilities of key states – and historical enemies - in the Middle East, look well-founded.

SINGAPORE - Saudi crude oil supplies for China"s privately-run Zhejiang Petrochemical Corp will return to normal in October after a slight disruption last month following the attacks on Saudi Aramco"s facilities, two company officials said.

"There was an adjustment in September but operations are back to normal in October," Meng Fanqiu who heads Rongsheng International Trading Co in Singapore told Reuters. The trading unit procures crude for the refinery.

Drones and missiles hit Saudi Arabia"s oil facilities on Sept. 14 and reduced output at the world"s top exporter by half. The head of Saudi Aramco"s trading arm said on Monday the company had restored full oil production and capacity to the levels they were before the attacks.

Zhejiang Petrochemical, 51% owned by Rongsheng Holdings, operates a 400,000 barrels per day refinery, built on an island off the archipelago city of Zhoushan in east China. The refinery is integrated with a petrochemical complex led by a 1.2 million-tonne per year ethylene facility.

Saudi Aramco has signed agreements to acquire a 9% stake in the Zhejiang petrochemical project in the Chinese province of Zhejiang for an undisclosed price.

The Arabian company has signed a second agreement with Rongsheng Petrochemical, Juhua Group, and Tongkun Group, the other shareholders of Zhejiang Petrochemical, the holding company of the Chinese petrochemical project.

Saudi Aramco said that its involvement in the project will come with a long-term crude supply agreement and the ability to use Zhejiang Petrochemical’s large crude oil storage facility to cater to its customers in Asia.

Saudi Aramco CEO Amin Nasser said: “The agreements demonstrate our commitment to the Chinese market and help enhance the strategic integration of our downstream network in Asia. They will further strengthen our relationship with China and the Zhejiang province, setting the stage for more cooperation in the future.”

Last week, Saudi Aramco entered into a joint venture agreement with NORINCO Group and Panjin Sincen to develop a fully integrated refining and petrochemical complex in Panjin in another Chinese province Liaoning.

The joint venture, called Huajin Aramco Petrochemical is expected to invest over $10bn to build what will be a 300 thousand barrel per day refinery, equipped with a 1.5 million metric tons per annum (mmtpa) ethylene cracker and a 1.3 mmtpa PX unit.

The purchase, which is part of Aramco’s strategy to expand its downstream operations, will be completed later this year, they said in a joint statement.

Aramco will start meeting international bond investors this week for its debut in the international capital markets, opening its books to investor scrutiny for the first time.

Saudi Aramco signed an agreement in April with a consortium of state-owned Indian refiners to participate in a $44 billion refinery project on the country’s west coast.

Top oil exporter Saudi Arabia is expected to cut February prices for heavier crude grades sold to Asia due to weaker fuel oil margins, respondents to a Reuters survey said on Thursday.

Saudi Aramco said it has awarded the first major contract in the planned construction of a $5.2 billion shipyard complex designed to reduce Saudi Arabia"s dependence on oil exports.

Apparently confirming the view of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) that the U.S. is now regarded as just another one of its partners in a new global order that would see Beijing and its allies share the leadership position with Washington, Saudi Arabia last week reiterated its commitment to China as its “most reliable partner and supplier of crude oil,” along with broader assurances of its ongoing support in several other areas. That MbS seemingly now sees the U.S. as a partner just for its security considerations, with no meaningful quid pro quo on Saudi Arabia’s part, whilst regarding China as its key partner economically and Russia as its key partner in energy matters, should not surprise the U.S.

Back in March last year it was made clear enough at the annual China Development Forum hosted in Beijing, when Aramco chief executive officer, Amin Nasser said: “Ensuring the continuing security of China’s energy needs remains our highest priority - not just for the next five years but for the next 50 and beyond.” And yet, the U.S. is surprised by the apparent finalisation of the transition of Saudi Arabia away from Washington and towards China, which effectively marks the end of the 1945 core agreement between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia that defined their relationship up until extremely recently. This transition has been seen most recently in the refusal of MbS to take a telephone call from President Joe Biden in which he was to ask for his help in bringing down economy-crimping high energy prices and then in the huge cut in collective OPEC oil production that has only added to energy-driven inflationary fears for global economies.

Given the peremptory way in which the core 1945 agreement was ended by MbS, Washington is angry too, as was evidenced in the highly pointed comments from several senior U.S. officials at the time of the OPEC cut, including from Biden himself, who said that: “There’s going to be some consequences for what they’ve done, with Russia [supporting oil prices by leading OPEC’s 2 million barrel per day (bpd) collective output cut]…I’m not going to get into what I’d consider and what I have in mind. But there will be – there will be consequences.” Just before Biden’s comments, John Kirby, the national security council spokesperson, echoed official doubts on the future of the U.S.-Saudi security relationship, as he said that Biden believed that the U.S. ought to “review the bilateral relationship with Saudi Arabia and take a look to see if that relationship is where it needs to be and that it is serving our national security interests,…in light of the recent decision by OPEC, and Saudi Arabia’s leadership [of it].”

Apparently careless of these ramifications, Saudi Arabia last week stated that, in addition to continuing in its role as China’s partner of choice in the oil market, the two countries would continue “close communication and strengthen co-operation to address emerging risks and challenges,” according to a joint communique from Saudi Energy Minister, Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman and Beijing"s National Energy Administrator, Zhang Jianhua. In the context of crude oil, according to Chinese Customs data, Saudi Arabia delivered 1.76 million bpd in shipments to China over the January to August period, marking an increase in its market share to 17.7 percent from 16.9 percent a year earlier.

Additionally, last week saw the two countries pledge to continue discussions on developing joint integrated refining and petrochemical complexes and to cooperate on the use of nuclear energy. Although flagged by Saudi Arabia and China as being ‘the peaceful use of nuclear energy’, the news just before Christmas 2021 that U.S. intelligence agencies had found that Saudi Arabia is now manufacturing its own ballistic missiles with the help of China – and given China’s long-running and extensive ‘assistance’ to Iran’s nuclear ambitions, as analysed in full in my latest book on the global oil markets - ongoing U.S. fears about what Beijing’s endgame might be in building out the nuclear capabilities of key states in the Middle East will not have been alleviated.

This latest round of talks and agreements comes very shortly after the signing of a multi-pronged memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the Saudi Arabian Oil Company – formerly the Saudi Arabian American Oil Company – ‘Aramco’, and the China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (Sinopec), which can be regarded as a critical step in China’s ongoing strategy to secure Saudi Arabia as a client state. As the president of Sinopec, Yu Baocai, himself put it: “The signing of the MoU introduces a new chapter of our partnership in the Kingdom…The two companies will join hands in renewing the vitality and scoring new progress of the Belt and Road Initiative [BRI] and [Saudi Arabia’s] Vision 2030.”

Crucially for China’s long-term plans in Saudi Arabia, it also covers opportunities for the construction of a huge manufacturing hub in King Salman Energy Park that will involve the ongoing, on-the-ground presence on Saudi Arabian soil of significant numbers of Chinese personnel: not just those directly related to the oil, gas, petrochemicals, and other hydrocarbons activities, but also a small army of security personnel to ensure the safety of China’s investments. At that point in early 2021, Aramco had a 25 percent stake in the 280,000 bpd Fujian refinery in south China through a joint venture with Sinopec (and the U.S.’s ExxonMobil) and had also earlier agreed (in 2018) to buy a 9 percent stake in China’s 800,000 bpd ZPC refinery from Rongsheng. Several other joint projects between China and Saudi Arabia that had been agreed in principle were delayed due to a combination of the ongoing effects of Covid-19, Aramco’s crushing dividend repayment schedule, and concern from both countries – especially China – on how Washington might react to this clear threat to the U.S.’s own long-running interests in, and geopolitical relationship with, Saudi Arabia.

Just prior to this, June saw Saudi Aramco’s senior vice president downstream, Mohammed Y. Al Qahtani, announce the creation of a ‘one-stop shop’ provided by his company in China’s Shandong. “The ongoing energy crisis, for example, is a direct result of fragile international transition plans which have arbitrarily ignored energy security and affordability for all,” he said. “The world needs clear-eyed thinking on such issues. That’s why we highly admire China’s 14th Five Year Plan for prioritising energy security and stability, acknowledging its crucial role in economic development,” he added. The megaproject in Shandong, which is home to around 26 percent of China’s refining capacity and is a key destination for Saudi Aramco’s crude oil exports, will broadly involve the flagship Saudi oil and gas giant creating “stronger ties with the world’s largest oil exporter [that] would enhance China’s energy security, especially as we work on increasing our production capacity to 13 million barrels per day,” according to Al Qahtani. Aside from the fact that Saudi Arabia still cannot produce anywhere near 13 million barrels per day of crude oil, closer cooperation between Aramco and China will mean Saudi Arabia investing heavily in the build-out of a large, integrated downstream business across the country in tandem with its Chinese partners

Given the transition of Saudi Arabia away from the U.S. and towards China – and the senior Saudis do look at the issue in these terms, whatever they say publicly – there is also every reason to expect Riyadh to continue to back China’s efforts to undermine the power of the U.S. dollar in the global energy markets as well. Not only is Saudi Arabia now a prime mover in advancing the China-GCC Free Trade Agreement (FTA) – a key aim of which is to forge a “deeper strategic cooperation in a region where U.S. dominance is showing signs of retreat” – but also the Kingdom is now a prime advocate for switching away from the hegemony of U.S. dollars in the pricing of global oil and gas.

Just after China made a crucial face-saving offer to MbS to privately buy the entire 5 percent stake in Saudi Aramco that he originally wanted to float but could not entice Western investors to buy, the then-Saudi Vice Minister of Economy and Planning, Mohammed al-Tuwaijri, told a Saudi-China conference in Jeddah that: “We will be very willing to consider funding in renminbi and other Chinese products.” He added: “China is by far one of the top markets’ to diversify the funding…[and] we will also access other technical markets in terms of unique funding opportunities, private placements, panda bonds and others.” Moreover, recent reports state that long-running talks between Saudi Arabia and China for Saudi to price and receive payments for some of its oil sales in Chinese renminbi rather than in U.S. dollars have intensified in the past few months.

The changing roles played by China’s independent refineries are reflected in their relations with Middle East suppliers. In the battle to ensure their profitability and very survival, smaller Chinese teapots have adopted various measures, including sopping up steeply discounted oil from Iran. Meanwhile, Middle East suppliers, notably Saudi Aramco, are seeking to lock in Chinese crude demand while pursuing new opportunities for further investments in integrated downstream projects led by both private and state-owned companies.

In 2016, during the period of frenzied post-licensing crude oil importing by Chinese independents, Saudi Arabia began targeting teapots on the spot market, as did Kuwait. Iran also joined the fray, with the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) operating through an independent trader Trafigura to sell cargoes to Chinese independents.[27] Since then, the coming online of major new greenfield refineries such as Rongsheng ZPC and Hengli Changxing, and Shenghong, which are designed to operate using medium-sour crude, have led Middle East producers to pursue long-term supply contracts with private Chinese refiners. In 2021, the combined share of crude shipments from Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, and Kuwait to China’s independent refiners accounted for 32.5%, an increase of more than 8% over the previous year.[28] This is a trend that Beijing seems intent on supporting, as some bigger, more sophisticated private refiners whose business strategy aligns with President Xi’s vision have started to receive tax benefits or permissions to import larger volumes of crude directly from major producers such as Saudi Arabia.[29]

The shift in Saudi Aramco’s market strategy to focus on customer diversification has paid off in the form of valuable supply relationships with Chinese independents. And Aramco’s efforts to expand its presence in the Chinese refining market and lock in demand have dovetailed neatly with the development of China’s new greenfield refineries.[30] Over the past several years, Aramco has collaborated with both state-owned and independent refiners to develop integrated liquids-to-chemicals complexes in China. In 2018, following on the heels of an oil supply agreement, Aramco purchased a 9% stake in ZPC’s Zhoushan integrated refinery. In March of this year, Saudi Aramco and its joint venture partners, NORINCO Group and Panjin Sincen, made a final investment decision (FID) to develop a major liquids-to-chemicals facility in northeast China.[31] Also in March, Aramco and state-owned Sinopec agreed to conduct a feasibility study aimed at assessing capacity expansion of the Fujian Refining and Petrochemical Co. Ltd.’s integrated refining and chemical production complex.[32]

Commenting on the rationale for these undertakings, Mohammed Al Qahtani, Aramco’s Senior Vice-President of Downstream, stated: “China is a cornerstone of our downstream expansion strategy in Asia and an increasingly significant driver of global chemical demand.”[33] But what Al Qahtani did notsay is that the ties forged between Aramco and Chinese leading teapots (e.g., Shandong Chambroad Petrochemicals) and new liquids-to-chemicals complexes have been instrumental in Saudi Arabia regaining its position as China’s top crude oil supplier in the battle for market share with Russia.[34] Just a few short years ago, independents’ crude purchases had helped Russia gain market share at the expense of Saudi Arabia, accelerating the two exporters’ diverging fortunes in China. In fact, between 2010 and 2015, independent refiners’ imports of Eastern Siberia Pacific Ocean (ESPO) blend accounted for 92% of the growth in Russian crude deliveries to China.[35] But since then, China’s new generation of independents have played a significant role in Saudi Arabia clawing back market share and, with Beijing’s assent, have fortified their supply relationship with the Kingdom.

As Chinese private refiners’ number, size, and level of sophistication has changed, so too have their roles not just in the domestic petroleum market but in their relations with Middle East suppliers. Beijing’s import licensing and quota policies have enabled some teapot refiners to maintain profitability and others to thrive by sourcing crude oil from the Middle East. For their part, Gulf producers have found Chinese teapots to be valuable customers in the spot market in the battle for market share and, especially in the case of Aramco, in the effort to capture the growth of the Chinese domestic petrochemicals market as it expands.

BEIJING (Reuters) - Rongsheng Petrochemical , the listed arm of a major shareholder in one of China"s biggest private oil refineries, expects demand for energy and chemical products to return to normal in the country in the second half of this year.

Rongsheng expects to start trial operations of the second phase of the refining project, adding another 400,000 bpd of refining capacity and 1.4 million tonnes of ethylene production capacity in the fourth quarter of 2020.

"We expect the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on energy and chemicals to have basically faded in spite of the possibility of new waves of outbreak," said Quan Weiying, board secretary of Rongsheng, in response to Reuters questions in an online briefing.

But Li Shuirong, president of Rongsheng, told the briefing that it was still in the process of applying for an export quota and would adjust production based on market demand. (Reporting by Muyu Xu and Chen Aizhu; Editing by Jacqueline Wong)

8613371530291

8613371530291