su rongsheng in stock

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

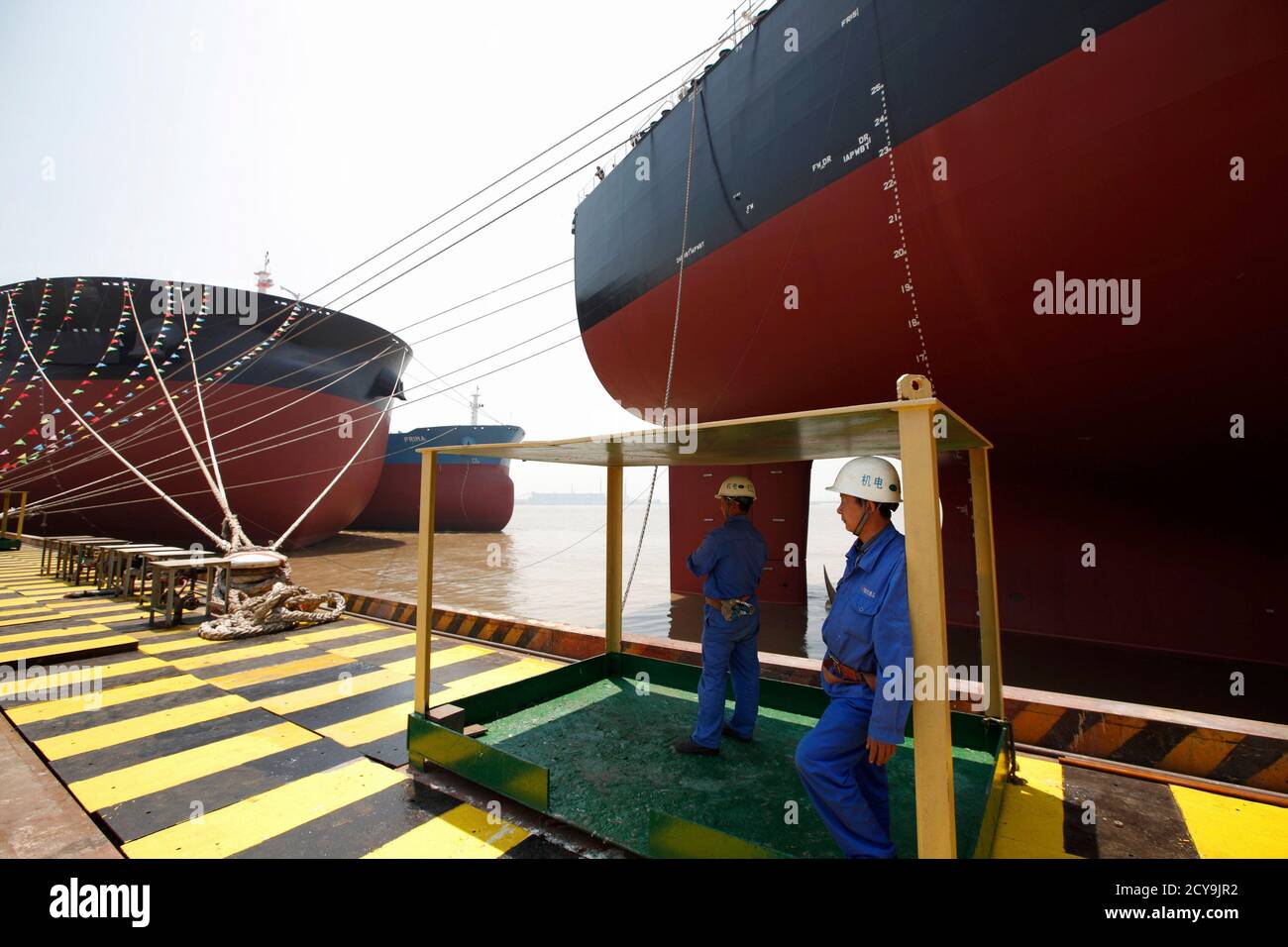

HONG KONG (Reuters) - Jiangsu Rongsheng Heavy Industries Co Ltd has appointed Morgan Stanleyand JP Morganto finalize plans for its long-awaited IPO in Hong Kong, aiming to raise up to $1.5 billion in the fourth quarter, sources told Reuters on Tuesday.

This is Rongsheng’s latest bid to go public after it failed to raise more than $2 billion from a planned IPO in Hong Kong in 2008, mainly as a result of the global financial crisis.

Rongsheng"s early main shareholders included an Asia investment arm of Goldman Sachs, U.S. hedge fund D.E. Shaw and New Horizon, a China fund founded by the son of Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao.

The three investors sold off their stakes in Rongsheng for a profit early this year, said the sources familiar with the situation. Representatives for the banks, funds and Rongsheng all declined to comment.

Rongsheng’s revived IPO plan comes at a challenging time. Smaller domestic rival, New Century Shipbuilding, slashed its Singapore IPO in half last week, planning to raise up to $560 million from the originally planned $1.24 billion due to weak market conditions.

Given uncertainty in the global shipbuilding business environment as well as growing concerns over a huge flow of fund-raising events in Hong Kong, investment bankers suggest the potential size for Rongsheng could be $1 billion to $1.5 billion, according to the sources.

Rongsheng is seeking to tap capital markets to fund fast growth and aims to catch up with bigger state-owned rivals such as Guangzhou Shipyard International Co Ltd.

Rongsheng won a $484 million deal to build four ships for Oman Shipping Co last year. The vessels would carry exports from an iron ore pellet plant in northern Oman which is expected to begin production in the second half of 2010.

HONG KONG, July 5 (Reuters) - China Rongsheng Heavy Industries Group, China’s largest private shipbuilder, appealed for financial help from the Chinese government and big shareholders on Friday after cutting its workforce and delaying payments to suppliers.

Analysts said the company could be the biggest casualty of a local shipbuilding industry suffering from overcapacity and shrinking orders amid a global shipping downturn. New ship orders for Chinese builders fell by about half last year.

Hours after China Rongsheng made its appeal in a filing to the Hong Kong stock exchange, where the company is listed, Beijing vowed to bring about the orderly closure of some factories in industries plagued by overcapacity.

The statement by the State Council, or cabinet, laid out broad plans to ensure banks support the kind of economic rebalancing Beijing wants as it looks to focus more on high-end manufacturing. It did not mention any specific industries or companies and there was no suggestion it was referring to Rongsheng.

China Rongsheng said it was expecting a net loss for the six months that ended June 30 from a year earlier, according to the filing. It gave no figures.

The company reported a net loss of 572.6 million yuan ($93.47 million) in 2012, its worst-ever, despite getting government subsidies of 1.27 billion yuan in that year, its latest annual report shows.

Rongsheng shares plunged 16 percent to a record low in heavy turnover on Friday, leaving its market capitalisation at just under $1 billion. The Hang Seng Index climbed 1.9 percent. China Rongsheng is down 28.2 percent on the year.

“Obviously it’s bad with the fact that you have a profit warning and there is a request to ease financial pressure through the government,” said Nathan Snyder, a transport analyst at CLSA.

In its filing, China Rongsheng said some workers had been made redundant, although it gave no numbers or timeframe for the losses. The company did not immediately respond to requests for more information.

Analysts said the company was suffering partly because of its reliance on building bulk carriers that ship iron ore from producer nations such as Brazil to China. The bulk market accounted for about 58 percent of its orderbook.

That segment was under pressure due to a slowdown in global steel production, relatively high iron ore port inventory levels and a wave of new ships hitting the market in 2011-12, Citigroup said.

China Rongsheng has said it won only two shipbuilding orders worth $55.6 million last year when its target was $1.8 billion worth of contracts. This year, it received orders to build two drilling rigs used in oil exploration, worth $360 million.

While the Chinese shipbuilding industry faced “unprecedented challenges”, China Rongsheng’s board was confident management could ease pressure on working capital in the near future and maintain normal operations, the company said in the filing.

It was coping with tightened cash flow by delaying payments to suppliers and workers, the filing added. The company denied claims suppliers had towed away machinery from its Nantong production base in eastern Jiangsu province, near Shanghai.

According to its December 2012 annual report, issued on March 26, China Rongsheng’s cash and cash equivalents fell to 2.1 billion yuan from 6.3 billion yuan a year ago.

“The group is ... actively seeking financial support from the government and the substantial shareholders of the company, and increasing its efforts in negotiations with its customers to maximise the collection of receivables,” China Rongsheng said in the filing.

A note from Macquarie Equities research said the statement highlighted the “severity” of China Rongsheng’s liquidity problems, adding this was not necessarily representative of the wider sector.

It said other listed Chinese shipyards were not as leveraged as China Rongsheng. The loan from Zhang was a surprise, it said, showing how badly the company needed cash.

“Rongsheng will need to address the problems immediately to reassure the market,” said Martin Rowe, managing director of Clarkson Asia Limited, a global shipping services provider.

The Chinese government has been trying to support the domestic shipping industry since the 2008 financial crisis, and local media reports said this week Beijing was considering policies to revive the shipbuilding business.

Data are provided "as is" for informational purposes only and are not intended for trading purposes. FactSet (a) does not make any express or implied warranties of any kind regarding the data, including, without limitation, any warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose or use; and (b) shall not be liable for any errors, incompleteness, interruption or delay, action taken in reliance on any data, or for any damages resulting therefrom. Data may be intentionally delayed pursuant to supplier requirements.

Mutual Funds & ETFs: All of the mutual fund and ETF information contained in this display, with the exception of the current price and price history, was supplied by Lipper, A Refinitiv Company, subject to the following: Copyright 2019© Refinitiv. All rights reserved. Any copying, republication or redistribution of Lipper content, including by caching, framing or similar means, is expressly prohibited without the prior written consent of Lipper. Lipper shall not be liable for any errors or delays in the content, or for any actions taken in reliance thereon.

Rongsheng Petro Chemical Co, Ltd. specialises in the production and marketing of petrochemical and chemical fibres. Products include PTA yarns, fully drawn polyester yarns (FDY), pre-oriented polyester yarns (POY), polyester textured drawn yarns (DTY), polyester filaments and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) slivers.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Privately owned unaffiliated refineries, known as “teapots,”[3] mainly clustered in Shandong province, have been at the center of Beijing’s longtime struggle to rein in surplus refining capacity and, more recently, to cut carbon emissions. A year ago, Beijing launched its latest attempt to shutter outdated and inefficient teapots — an effort that coincides with the emergence of a new generation of independent players that are building and operating fully integrated mega-petrochemical complexes.[4]

The changing roles played by China’s independent refineries are reflected in their relations with Middle East suppliers. In the battle to ensure their profitability and very survival, smaller Chinese teapots have adopted various measures, including sopping up steeply discounted oil from Iran. Meanwhile, Middle East suppliers, notably Saudi Aramco, are seeking to lock in Chinese crude demand while pursuing new opportunities for further investments in integrated downstream projects led by both private and state-owned companies.

China’s “teapot” refineries[5] play a significant role in refining oil and account for a fifth of Chinese crude imports.[6] Historically, teapots conducted most of their business with China’s major state-owned companies, buying crude oil from and selling much of their output to them after processing it into gasoline and diesel. Though operating in the shadows of China’s giant national oil companies (NOCs),[7] teapots served as valuable swing producers — their surplus capacity called on in times of tight markets.

Yet, the Chinese government has spent the better part of two decades trying to consolidate the country’s sprawling independent refining sector by starving private operators of access to imported crude oil and targeting the smallest, least efficient plants for closure.[8] In 2011, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) issued guidelines to eliminate small refineries to achieve economies of scale and improve efficiencies. Nevertheless, policies meant to discourage activity had the opposite effect, as most of the units that were earmarked for suspension expanded to stay open.[9]

2021 marked the start of the central government’s latest effort to consolidate and tighten supervision over the refining sector and to cap China’s overall refining capacity.[14] Besides imposing a hefty tax on imports of blending fuels, Beijing has instituted stricter tax and environmental enforcement[15] measures including: performing refinery audits and inspections;[16] conducting investigations of alleged irregular activities such as tax evasion and illegal resale of crude oil imports;[17] and imposing tighter quotas for oil product exports as China’s decarbonization efforts advance.[18]

The politics surrounding this new class of greenfield mega-refineries is important, as is their geographical distribution. Beijing’s reform strategy is focused on reducing the country’s petrochemical imports and growing its high value-added chemical business while capping crude processing capacity. The push by Beijing in this direction has been conducive to the development of privately-led mega refining and petrochemical projects, which local officials have welcomed and staunchly supported.[20]

Yet, of the three most recent major additions to China’s greenfield refinery landscape, none are in Shandong province, home to a little over half the country’s independent refining capacity. Hengli’s Changxing integrated petrochemical complex is situated in Liaoning, Zhejiang’s (ZPC) Zhoushan facility in Zhejiang, and Shenghong’s Lianyungang plant in Jiangsu.[21]

As China’s independent oil refining hub, Shandong is the bellwether for the rationalization of the country’s refinery sector. Over the years, Shandong’s teapots benefited from favorable policies such as access to cheap land and support from a local government that grew reliant on the industry for jobs and contributions to economic growth.[22] For this reason, Shandong officials had resisted strictly implementing Beijing’s directives to cull teapot refiners and turned a blind eye to practices that ensured their survival.

But with the start-up of advanced liquids-to-chemicals complexes in neighboring provinces, Shandong’s competitiveness has diminished.[23] And with pressure mounting to find new drivers for the provincial economy, Shandong officials have put in play a plan aimed at shuttering smaller capacity plants and thus clearing the way for a large-scale private sector-led refining and petrochemical complex on Yulong Island, whose construction is well underway.[24] They have also been developing compensation and worker relocation packages to cushion the impact of planned plant closures, while obtaining letters of guarantee from independent refiners pledging that they will neither resell their crude import quotas nor try to purchase such allocations.[25]

To be sure, the number of Shandong’s independent refiners is shrinking and their composition within the province and across the country is changing — with some smaller-scale units facing closure and others (e.g., Shandong Haike Group, Shandong Shouguang Luqing Petrochemical Corp, and Shandong Chambroad Group) pursuing efforts to diversify their sources of revenue by moving up the value chain. But make no mistake: China’s teapots still account for a third of China’s total refining capacity and a fifth of the country’s crude oil imports. They continue to employ creative defensive measures in the face of government and market pressures, have partnered with state-owned companies, and are deeply integrated with crucial industries downstream.[26] They are consummate survivors in a key sector that continues to evolve — and they remain too important to be driven out of the domestic market or allowed to fail.

In 2016, during the period of frenzied post-licensing crude oil importing by Chinese independents, Saudi Arabia began targeting teapots on the spot market, as did Kuwait. Iran also joined the fray, with the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) operating through an independent trader Trafigura to sell cargoes to Chinese independents.[27] Since then, the coming online of major new greenfield refineries such as Rongsheng ZPC and Hengli Changxing, and Shenghong, which are designed to operate using medium-sour crude, have led Middle East producers to pursue long-term supply contracts with private Chinese refiners. In 2021, the combined share of crude shipments from Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, and Kuwait to China’s independent refiners accounted for 32.5%, an increase of more than 8% over the previous year.[28] This is a trend that Beijing seems intent on supporting, as some bigger, more sophisticated private refiners whose business strategy aligns with President Xi’s vision have started to receive tax benefits or permissions to import larger volumes of crude directly from major producers such as Saudi Arabia.[29]

The shift in Saudi Aramco’s market strategy to focus on customer diversification has paid off in the form of valuable supply relationships with Chinese independents. And Aramco’s efforts to expand its presence in the Chinese refining market and lock in demand have dovetailed neatly with the development of China’s new greenfield refineries.[30] Over the past several years, Aramco has collaborated with both state-owned and independent refiners to develop integrated liquids-to-chemicals complexes in China. In 2018, following on the heels of an oil supply agreement, Aramco purchased a 9% stake in ZPC’s Zhoushan integrated refinery. In March of this year, Saudi Aramco and its joint venture partners, NORINCO Group and Panjin Sincen, made a final investment decision (FID) to develop a major liquids-to-chemicals facility in northeast China.[31] Also in March, Aramco and state-owned Sinopec agreed to conduct a feasibility study aimed at assessing capacity expansion of the Fujian Refining and Petrochemical Co. Ltd.’s integrated refining and chemical production complex.[32]

Commenting on the rationale for these undertakings, Mohammed Al Qahtani, Aramco’s Senior Vice-President of Downstream, stated: “China is a cornerstone of our downstream expansion strategy in Asia and an increasingly significant driver of global chemical demand.”[33] But what Al Qahtani did notsay is that the ties forged between Aramco and Chinese leading teapots (e.g., Shandong Chambroad Petrochemicals) and new liquids-to-chemicals complexes have been instrumental in Saudi Arabia regaining its position as China’s top crude oil supplier in the battle for market share with Russia.[34] Just a few short years ago, independents’ crude purchases had helped Russia gain market share at the expense of Saudi Arabia, accelerating the two exporters’ diverging fortunes in China. In fact, between 2010 and 2015, independent refiners’ imports of Eastern Siberia Pacific Ocean (ESPO) blend accounted for 92% of the growth in Russian crude deliveries to China.[35] But since then, China’s new generation of independents have played a significant role in Saudi Arabia clawing back market share and, with Beijing’s assent, have fortified their supply relationship with the Kingdom.

Smaller Chinese independents have been less fortunate, hit hard not just by tougher domestic regulation but by soaring crude oil prices.[36] US-led sanctions flowing from the war in Ukraine have compounded the pressure on teapots, which prior to the conflict had sourced about a fifth of their crude oil from Russia. Soaring oil tanker freight rates and the refusal of Chinese banks to issue letters of credit for Russian crude have choked off much of this supply, though some private refiners have compensated by using cash transfers to pay for Russian ESPO blend crude.[37]

Meanwhile, though, enticed by discounted prices Chinese independents in Shandong province have continued to scoop up sanctioned Iranian oil, especially as their domestic refining margins have thinned due to tight regulatory scrutiny. In fact, throughout the period in which Iran has been under nuclear-related sanctions, Chinese teapots have been a key outlet for Iranian oil, which they reportedly unload from reflagged vessels representing themselves as selling oil from Oman and Malaysia.[38] China Concord Petroleum Company (CCPC), a Chinese logistics firm, remained a pivotal player in the supply of sanctioned oil from Iran, even after it was blacklisted by Washington in 2019.[39] Although Chinese state refiners shun Iranian oil, at least publicly, because of US sanctions, private refiners have never stopped buying Iranian crude.[40] And in recent months, teapots have been at the forefront of the Chinese surge in crude oil imports from Iran.[41]

China’s small-scale, inefficient “first generation” teapot refiners have come under mounting market pressure, as well as closer government scrutiny and tightened regulation. Though some have already been shuttered and others face imminent closure, dozens of China’s teapots, concentrated mainly in Shandong province, continue to operate thanks to the creative defensive measures they have employed and the important role they play in local economies.

Vertical integration along the value chain has become a global trend in the petrochemical industry, specifically in refining and chemical operations. China’s drive to self-sufficiency in chemicals is a key factor powering this worldwide trend.[42] And it is the emergent “second generation” of independent refiners that it is helping make China the frontrunner in developing massive liquids-to-chemicals complexes. Following Beijing’s lead, Shandong officials appear determined to follow this trend rather than risk being left in its wake.

As Chinese private refiners’ number, size, and level of sophistication has changed, so too have their roles not just in the domestic petroleum market but in their relations with Middle East suppliers. Beijing’s import licensing and quota policies have enabled some teapot refiners to maintain profitability and others to thrive by sourcing crude oil from the Middle East. For their part, Gulf producers have found Chinese teapots to be valuable customers in the spot market in the battle for market share and, especially in the case of Aramco, in the effort to capture the growth of the Chinese domestic petrochemicals market as it expands.

Responding to requests for information about China has become an essential part of an Asia researcher"s life. Goldman Sachs (Asia) oil and gas and chemicals analyst and co-head of research Paul Bernard estimates that his China-related research has tripled in three years, to about 70 percent of his total workload. China now exerts such an influence on prices in his sectors that it "feeds into a view on stocks, whether they be in Asia, Europe or the U.S." His team"s recent buys on South Korea"s LG Chem and Taiwan"s Formosa Plastics Corp. were both based in large part on growing Chinese demand for their petrochemicals products.

Consider the experience of J.P. Morgan Securities" Hong Kong,based consumer goods analyst Charles Dutton. The researcher recently had to evaluate the expansion plans of Hong Kong,based clothes retailer Esprit Asia Holdings and South Korean discount chain Shinsegae Co. With most developed Asian markets near saturation, both are looking to China for long-term sustainable growth. Esprit wants to achieve sales of more than $100 million from China in the next few years, while Shinsegae plans to spend $30 million to open two stores in Shanghai as a prelude to creating a 40-outlet Chinese network in the next eight years.

"Exposure to China is regarded as a big positive because it"s one of the only countries in Asia recording strong economic growth. Investor demand is huge, but the number of companies with large exposure is very limited," says Dutton. Both stocks surged on news of their China plans, and Esprit"s has increased 63 percent since the turn of the year to hit HK$14.70 ($1.88) in mid-April. Shinsegae"s has risen more than 40 percent in that time following a huge gain last year.

But do their strategies make any sense? There are few precedents for looking at foreign ventures in China. The legal system offers little guidance to new businesses. And no one is entirely sure what the local demand for a given product or service is. It will be left to pioneering researchers like Dutton and his cohorts to figure out whether these initiatives will work.

Certainly, China presents all analysts with problems as well as opportunities. Local companies" incomplete, inaccurate or nonexistent disclosure about everything from intracompany loans to profits is the bane of every Asia researcher"s life. Some Chinese executives, a UBS Warburg study reports, "do not regard a profit warning one day before the official release as being too late."

The consequences of these failures can be devastating to both analysts and investors. Onetime stock market darling Guangdong Kelon Electrical Appliances Co., a Guangzhou-based white goods manufacturer, ran into trouble late last year when the Hong Kong stock exchange suspended it for three months for failing to disclose that it had advanced 1.26 billion renminbi ($152 million) to its parent, Guangdong Kelon (Rongsheng). The stock fell 31 percent as news of the inquiry began to leak out. It later rose when the debt turned out to be smaller than originally anticipated. "There are domestic companies that you can invest in, but they tend to be a little bit suspicious-looking," says consumer analyst Angela Moh (leader of the No. 1 team this year) of Morgan Stanley. "You just have to be very careful."

Not all of this research effort is profitable. Morgan Stanley"s Vaudry calls it a "loss-leader" as near-term investments are made, while another research chief more artfully suggests that profits lie "just beyond the horizon." Driving the recent China-mania is a "fear of missing the train," concedes Michael Oertli, head of Asia research at UBS Warburg. Throughout the 1990s, however, repeated flashes of foreign investor interest in the potential of this huge, impoverished country failed to translate into meaningful business opportunities.

Still, research directors and investors believe that China"s recent entry into the WTO marks a new chapter in the story. As a result, they"re shifting resources to the mainland. Morgan Stanley plans to put four or five analysts in Shanghai this year, and UBS"s Oertli has told his Hong Kong,based China analysts that they can move to the firm"s Shanghai office any time they want. CLSA Emerging Markets, BNP Paribas Peregrine and HSBC Securities are negotiating to form joint ventures with local firms.

Much of this activity is based on prospective riches that may not materialize. Investment bankers estimate that China-related IPOs and equity issues could raise $200 billion over the next decade. The Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share markets list more than 1,000 companies, with a combined capitalization of $500 billion, versus $494 billion for the Hong Kong exchange. Commission revenue from China"s A-share markets now rivals that from Asia"s other major brokerage markets: South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. "China is probably the largest investment banking story in the world," says CLSA research chief Edmund Bradley. "It"s not easy making money, but people have to position for the long haul."

That test may soon arrive , Asia stocks got off to a fast start in 2002. In South Korea the Kospi surged 32 percent through early April, while Taiwan gained 10 percent. Even devastated markets in Southeast Asia (see Emerging Markets, page 87) rallied in the first quarter. Indonesia was up 31 percent, Thailand 30 percent, Malaysia 18 percent, the Philippines 17 percent and Singapore 10 percent. Says UBS"s Oertli, "Asia is one of the few places on earth making more money this year than last, over the same time period."

The turnaround couldn"t have come at a better time. A grim final quarter (a 29 percent decline for Asia shares) ruined what would have been a solid year and resulted in a 6 percent loss for 2001. Coupled with a more than 30 percent slide in 2000, the poor markets cost many professionals, including analysts, their jobs. One research head estimates that investment banks sliced their Asia staffs by about 25 percent in 2001. Cutbacks in research departments probably averaged closer to 10 to 15 percent. Says Miel Bakker, co-head of research with Goldman Sachs (Asia). "Nobody made real money, and a lot of people lost money."

The cutbacks no doubt affected the rankings of this year"s Asia Research Team. Last year"s No. 1 firm, Merrill Lynch, reduced its overall Asia head count by 25 percent and sold its brokerage operation in the Philippines to a management group that renamed it Philippines Equity Partners (which wins a runner-up position in this year"s rankings). Following the job cuts, Merrill Lynch slips to fourth this year, with a net reduction of seven positions on the team. Taking the laurels is UBS Warburg, which has been expanding its research coverage worldwide and had already improved its position to No. 2 last year from No. 3 the previous year. In 2002 Credit Suisse First Boston and Morgan Stanley, each of which commands four additional positions on the team, rank second and third, respectively.

Consolidation of investment banking in Asia continues at a rapid pace. Indosuez W.I. Carr Securities withdrew from Asia ex-Japan in November with the loss of 350 jobs. Like Merrill Lynch, HSBC Securities shuttered its operation in the Philippines in November and also departed Indonesia. In August Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein abandoned Asia with the loss of 250 jobs; SG Securities cut its research strength by some 60 percent, to 40 analysts.

The prevailing air of caution isn"t preventing a vigorous round of job-hopping. Most notably, J.P. Morgan snagged Bhavin Shah, who led CSFB"s No. 1, ranked Technology/Semiconductors team until late February. Now heading J.P. Morgan"s Asia-Pacific technology research, Shah was "the door-opener for CSFB," says one research head. Although the principals won"t comment, Shah is thought to have received an annual compensation package of more than $2 million. His former boss, CSFB research chief Sung June Hwang, believes that CSFB"s 18-person tech team, now headed by Ashis Kumar (who leads the firm"s No. 2,ranked team for India research and its first-place Technology/IT Services unit), will rise to the occasion. The episode, sighs Hwang, shows "how aggressive this market is becoming."

Few would disagree, as just about everyone is jockeying for position in China and the rest of Asia. In April Citigroup/Salomon Smith Barney hired top-ranked equity strategist Ajay Kapur from Morgan Stanley. Joining Kapur is his two-person team of Narendra Singh and Elaine Chu. UBS Warburg pulled Sharon Su (leader of the No. 1 Taiwan team and the No. 1 Technology/Hardware team) from ABN Amro Asia.

Still, when it came to hiring, no one matched Deutsche Bank. Starting virtually from scratch, it hired more than 60 analysts in 2001, setting off complaints about its impact on salaries and the viability of the operation. Asia-Pacific ex-Japan equities chief Edouard Peter is unapologetic, saying only four of his hires received above-market packages, and he dismisses predictions that the firm will eventually have to cut back. "If people think we are all of a sudden going to fall apart, then they are not looking at what we"ve just done," Peter says. The firm, he notes, has grown successfully in Europe, the U.S. and Japan and now is aiming for similar results in Asia. That hasn"t stopped the carping: "It will all unravel when guarantees paid to new recruits expire in a year or two," scoffs a rival. Clearly, the competition to provide the best research in China , and all of Asia , has only just begun.

To find out whom the largest institutional investors turn to for advice on Asia ex-Japan, Institutional Investor sent a questionnaire covering more than 25 industry categories, investment specialties and countries to the directors of research and heads of investment at approximately 400 institutions and investment counseling firms that are major investors in the region. Included were select money managers in the Asia 100, our ranking of the largest institutional fund managers in Asia; we also tapped directories and industry data sources to ensure the completeness of the survey universe. Well over half of these institutions responded. The sector lineup remains largely unchanged from last year. Modifications include the addition of a Media category, the deletion of the Internet category and the separation of Technology into three sectors: Technology/Hardware, Technology/IT Services and Technology/Semiconductors. In addition, we have recast last year"s Oil & Gas category to include Chemicals, which had been a separate category.

Respondents were asked to reply themselves, to survey their money managers or to circulate the questionnaire through their own research departments to poll individual analysts. Those who did not respond were contacted to determine if they would be willing to participate over the telephone. After the questionnaires were returned, our reporters spent weeks interviewing investors to learn more about their choices. In addition, many of the winners were contacted to clarify points that their clients had raised. The names of those surveyed and the institutions they work for are kept confidential to ensure their continuing cooperation.

The ranking was compiled by Institutional Investor under the direction of Senior Editor Jane B. Kenney and Senior Associate Editor Tucker Ewing. Contributing Editor Kevin Hamlin wrote the overview. Reporter/Researcher Suzanne Lorge and Contributing Editors Andrew Bloomenthal, Jeanne Burke, Mary Dubas, Mark Frankel, Ben Mattlin, Scott McMurray and Mike Sisk wrote or edited the sector reports that follow.

8613371530291

8613371530291