first step act safety valve supplier

The Federal Safety Valve law permits a sentence in a drug conviction to go below the mandatory drug crime minimums for certain individuals that have a limited prior criminal history. This is a great benefit for those who want a second chance at life without sitting around incarcerated for many years. Prior to the First Step Act, if the defendant had more than one criminal history point, then they were ineligible for safety valve. The First Step Act changed this, now allowing for up to four prior criminal history points in certain circumstances.

The First Step Act now gives safety valve eligibility if: (1) the defendant does not have more than four prior criminal history points, excluding any points incurred from one point offenses; (2) a prior three point offense; and (3) a prior two point violent offense. This change drastically increased the amount of people who can minimize their mandatory sentence liability.

Understanding how safety valve works in light of the First Step Act is extremely important in how to incorporate these new laws into your case strategy. For example, given the increase in eligible defendants, it might be wise to do a plea if you have a favorable judge who will likely sentence to lesser time. Knowing these minute issues is very important and talking to a lawyer who is an experienced federal criminal defense attorney in southeast Michigan is what you should do. We are experienced federal criminal defense attorneys and would love to help you out. Contact us today.

Safety Valve is a provision codified in 18 U.S.C. 3553(f), that applies to non-violent, cooperative defendants with minimal criminal record without a leadership enhancement convicted under several federal criminal statutes. Congress created Safety Valve in order to ensure that low-level participants of drug organizations were not disproportionately punished for their conduct.

Generally applying to drug crimes with a mandatory minimum, Safety Valve has two major benefits for individuals charged with those crimes. Specifically, the two benefits of Safety Valve are:

The first benefit of Safety Valve is the ability to receive a sentence below a mandatory minimum on certain types of drug cases. Some drug charges have a mandatory minimum i.e. 5 years, 10 years. That means even if the person’s guidelines are lower than the mandatory minimum and the judge wants the sentence the individual below the mandatory minimum, the judge is legally unable to do so because that would be an illegal plea. If the Court determines that the individual meets the requirements of Safety Valve under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), the Judge is able to sentence the individual to a term that is less than the mandatory minimum.

The second benefit of safety valve is a two-point reduction in total offense conduct. Since 2009, federal sentencing guidelines are discretionary rather than binding. With that being said, federal sentencing guidelines still act as the Judge’s starting point in determining what the appropriate sentence on a case is. The higher the total offense score, the higher is the corresponding suggested sentencing range. A two-level difference can make a difference in months if not years of the sentence. Each point counts toward ensuring the lowest possible sentence.

The Defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager, or supervisor of others in the offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise, as defined in section 408 of the Controlled Substance Act, and

Not later than the time of the sentencing hearing, the defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

In order to establish eligibility for Safety Valve, the Defendant has the burden of proof to establish that s/he meets the five requirements by a preponderance of evidence. That is to say, the Defendant must prove by 51% that the Defendant meets all the requirements of eligibility. These five Safety Valve Requirements are explained in greater detail below.

The first requirement of Safety Valve is that the individual has a limited criminal record. The U.S. Sentencing Guidelines assign a certain number of points to prior convictions. The more serious the crime, and the longer the sentence, the more corresponding criminal history points it carries.

The second requirement of Safety Valve is that the individual did not use violence, credible threats of violence or possess a firearm or other dangerous weapon. Importantly, an individual can be disqualified from Safety Valve based on the conduct of co-conspirators, if the Defendant “aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused” the co-conspirator’s violence or possession of a firearm or another dangerous weapon. Thus, use of violence or possession of a weapon by a co-defendant does not disqualify someone from Safety Valve, unless the individual somehow helped or instructed the co-defendant to engage in that conduct.

To be disqualified from Safety Valve, possession of a firearm or another dangerous weapon can either be actual possession or constructive possession. Actual possession involves the individual having the gun in their hand or on their person. Constructive possession means that the individual has control over the place or area where the gun was located. Importantly, the possession of a firearm or a dangerous weapon needs to be related to the drug crime, as the statute requires possession of same “in connection with the offense.” However, “in connection with the offense” is a relatively loose standard, in that presence of the firearm or dangerous instrument in the same location as the drugs is enough to disqualify someone from Safety Valve.

The third requirement of Safety Valve is that the offense conduct did not result in death or serious bodily injury to any person. Serious bodily injury for the purposes of Safety Valve is defined as “injury involving extreme physical pain or the protracted impairment of a function of a bodily member, organ, or mental faculty; or requiring medical intervention such as surgery, hospitalization, or physical rehabilitation.”

The fourth requirement of Safety Valve is that the Defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager or supervisor of others in the office. An individual will be disqualified from safety valve if s/he exercised any supervisory power or control over another participant. Individuals who receive an enhancement for an aggravating role under §3B1.1 are not eligible for safety valve. Similarly, in order to be eligible for Safety Valve, an individual does not need to receive a minor participant role reduction.

Isolated instances of asking someone else for help do not result in the aggravating role enhancement. As the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit has held in United States v. McGregor, 11 F.3d 1133, 1139 (2d Cir. 1993), aggravated role enhancement did not apply to “one isolated instance of a drug dealer husband asking his wife to assist him in a drug transaction.” Similarly, in United States v. Figueroa, 682 F.3d 694, 697-98 (7th Cir. 2012); the Seventh Circuit declined to apply a leadership enhancement for a one-time request from one drug dealer to another to cover him on a sale.

The fifth and final Safety Valve requirement is that the individual meet with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for a Safety Valve proffer. A Safety Valve proffer is different from a regular proffer in that in a safety valve proffer, the individual is only required to truthfully proffer about his or her own conduct.

In contrast, in a non-safety valve proffer, the individual is required to truthfully provide information about his or her own criminal conduct, as well as the criminal conduct of others. In order to meet this requirement, the individual must provide a full and complete disclosure about their own criminal conduct, not just the allegations that are charged in the offense. There is no required time as to when someone goes in for a safety valve proffer, except that it must take place sometime “before sentencing.”

Not all charges with mandatory minimums qualify for Safety Valve relief. Rather, the criminal charge must be enumerated in 18 U.S.C. 3553(f). The following criminal charges are eligible for Safety Valve:

Under the First Step Act, the eligibility for Safety Valve relief was expanded to more individuals. Specifically, The First Step Act, P.L. 115-391, broadened the safety valve to provide relief for:

Prior to the enactment of the First Step Act, individuals could have a maximum of 1 criminal history point in order to be eligible for Safety Valve relief. Similarly, individuals who were prosecuted for possession of drugs aboard a vessel under the Maritime Drug Enforcement Act, were not eligible for Safety Valve relief. After the passing of the First Step Act, individuals prosecuted under Maritime Drug Enforcement Act, specifically 46 U.S.C. 70503 or 46 U.S.C. 70506 are eligible for Safety Valve relief.

Safety Valve is an important component of plea negotiations on federal drug cases and should always be explored by experienced federal counsel. If you have questions regarding your Safety Valve eligibility, please contact us today to schedule your consultation.

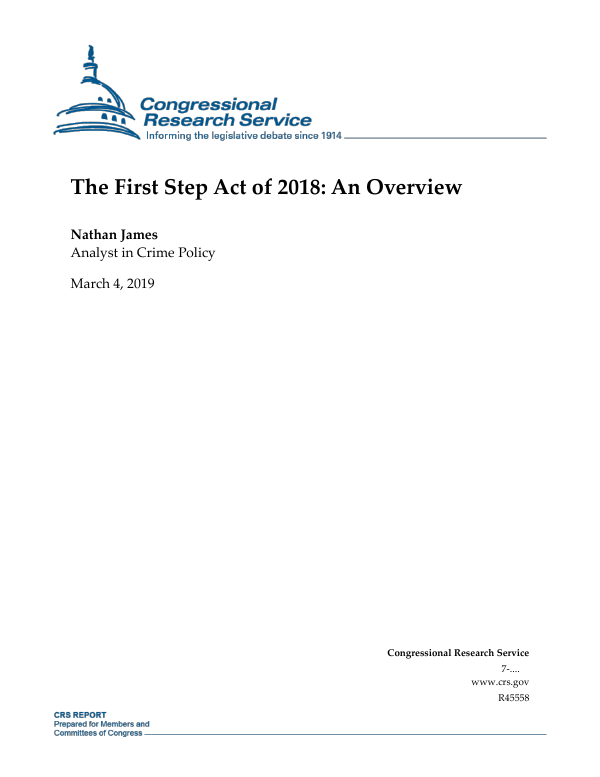

In December 2018, President Trump signed into law the First Step Act, which mostly involves prison reform, but also includes some sentencing reform provisions.

The key provision of the First Step Act that relates to sentencing reform concerns the “safety valve” provision of the federal drug trafficking laws. The safety valve allows a court to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum sentence for the crime, and to reduce the person’s offense level under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines by two points.

The First Step Act increases the availability of the safety valve by making it easier to meet the first requirement—little prior criminal history. Before the First Step Act, a person could have no more than one criminal history point. This generally means no more than one prior conviction in the last ten years for which the person received either probation or less than 60 days of prison time.

Section 402 of the First Step Act changes this. Now, a person is eligible for the safety valve if, in addition to meeting requirements 2-5 above, the defendant does not have:

This news has been published for the above source. Kiss PR Brand Story Press Release News Desk was not involved in the creation of this content. For any service, please contact https://story.kisspr.com.

In addition to making retroactive the Fair Sentencing Act’s correction of the disparity between sentences for crack and powder cocaine related offenses, a second hallmark of the FIRST STEP Act is the broadening of the safety valve provision, which dispenses with mandatory minium sentences under certain circumstances. While the Act does not provide for retroactivity of this provision, the United States Sentencing Commission estimates that this change will impact more than 2,000 defendants per year in the future. See Sentence and Prison Impact Estimate Summary (last viewed January 27, 2019).

The safety valve, codified at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) and also found in section 5C1.2 of the United States Sentencing Guidelines, permits judges to dispense with statutorily imposed mandatory minimum sentences with regard to violations of 21 U.S.C. §§ 841, 844, 846, 960 and 963, which involve the possession, manufacture, distribution, export and importation of controlled substances. Previously, in order to sentence a defendant without regard to the mandatory minimum sentences for these offenses, the court was required to find the following: 1) the defendant does not have more than one criminal history point; 2) the defendant did not use violence, threats, or possess a dangerous weapon or firearm in connection with the offense; 3) the offense did not result in death or serious bodily injury to any person; 4) the defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager or supervisor in the offense, and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise; and 5) the defendant truthfully provided information to the government concerning the offense. See 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)(1)-(5).

The FIRST STEP Act amends the aforementioned conditions by permitting judges to utilize the safety valve provision even where the defendant has up to four criminal history points, excluding all points for one-point offenses, which are generally minor crimes. However, defendants with prior three-point felony convictions and two-point violent felony convictions are still not permitted to utilize the safety valve. Additionally, the FIRST STEP Act adds 46 U.S.C. §§ 70503 and 70506, which involve the possession, distribution and manufacturing of controlled substances in international waters, to the list of offenses which are covered by the safety valve.

Hiring a top New York criminal defense attorney to defend you in any federal criminal prosecution or assist with any questions concerning the applicability of the FIRST STEP Act is crucial and will ensure that every viable defense or avenue for a sentencing reduction is explored and utilized on your behalf. Lawyers at the Law Offices of Jeffrey Lichtman have successfully handled countless federal cases, exploiting holes in the prosecution’s evidence to achieve the best possible result for our clients. Contact us today at (212) 581-1001 for a free consultation.

A three-judge panel for the US Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit initially agreed with the government’s interpretation of the First Step Act’s so-called safety valve provision. But in a highly fractured opinion issued Tuesday, the full court reversed, affirming Julian Garcon’s reduced sentence.

For reference, these refer to the statutory language of 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A) and 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B), which instruct the federal judge on how he or she shall sentence anyone convicted of the manufacture, distribution, or dispensing of a controlled substance (i.e., an illegal drug) or possession with intent to either of these things.

How do you know if you are charged with one of these federal drug crimes that come with a mandatory minimum sentence of either 5-to-40 years (a “b1B” case) or 10-to-life (a “b1A” case)? Read the language of your Indictment. It will specify the statute’s citation. If you do not have a copy of your Indictment, please feel free to contact my office and we can provide you a copy.

Can’t there be any way to get around that set-in-stone bottom line? Yes. There is also a statutory exception which allows the federal judge to dip below that mandatory minimum number of years in some situations. It is called the “Safety Valve” defense.

The law, 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), provides for an exception that allows the federal judge some leeway in drug crime convictions where he or she would otherwise be required to follow the mandatory minimum sentencing statute. This is the Safety Value statute. It states as follows:

(f)Limitation on Applicability of Statutory Minimums in Certain Cases.—Notwithstanding anyother provision of law, in the case of an offense under section 401, 404, or 406 of theControlled Substances Act(21 U.S.C. 841, 844, 846), section 1010 or 1013 of theControlled Substances Import and Export Act(21 U.S.C. 960, 963), or section 70503 or 70506 of title 46, the court shall impose a sentence pursuant to guidelines promulgated by the United States Sentencing Commission undersection 994 of title 28without regard to any statutory minimum sentence, if the court finds at sentencing, after the Government has been afforded the opportunity to make a recommendation, that—

(4)the defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager, or supervisor of others in the offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise, as defined in section 408 of theControlled Substances Act; and

(5)not later than the time of the sentencing hearing, the defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

The only way to allow for this exception to be applied in a federal sentencing hearing is for the defense to argue its application and to provide authenticated and admissible support for use of the Safety Valve.

How does the defense do this? It takes much more than referencing the exception to the general rule itself. The defense will have to demonstrate the convicted defendant meets the Safety Valve’s five (5) requirements.

For a successful safety valve defense, the defense has to show that the total Criminal History Points are four (4) or less. If you have a maximum of four Criminal History points, you have met the first criteria for the safety valve.

Note: prior to the passage of the First Step Act, things were much harsher. If the defense had even two Criminal History Points, then the accused was ineligible for the safety valve. The First Step Act increased the number of points, or score, from one to four as the maximum allowed for application of the safety valve. For more on the First Step Act, see The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 1 of 2 and The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 2 of 2.

Looking at the Safety Valve statute ( 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)), the second step in achieving application of the safety valve defense involves the circumstances of the underlying criminal activity and whether or not it involved violence of threats or violence, or if the defendant possessed a firearm at the time.

It has been my experience that it is pretty common for there to be a firearm of some sort involved in a federal drug crime prosecution. Here, the impact of Texas being a part of the Fifth Judicial District for the United States Court of Appeals (“Fifth Circuit”) is important.

In the USSG, two points are given (“enhanced”) for possessing a firearm in furtherance of a federal drug trafficking offense. See, USSG §2D1.10, entitled Endangering Human Life While Illegally Manufacturing a Controlled Substance; Attempt or Conspiracy.

Meanwhile, the Fifth Circuit has ruled that under the Safety Valve Statute, the standard for the government is much higher. According to their ruling, in order to be disqualified from application of the safety valve because of possession of a firearm, the defendant has to have been actually in possession of the firearm or in construction possession of it. See, US v. Wilson, 105 F.3d 219 (5th Cir. 1997).

This is the example of the importance of effective criminal defense representation, where research reveals that it is easier to achieve a safety valve defense with a reference to case law. The Fifth Circuit allows a situation where someone can get two (2) points under the USSG (“enhancement”) and still be eligible for the safety valve defense.

The commentary to § 5C1.2(2) provides that “[c]onsistent with [U.S.S.G.] § 1B1.3 (Relevant Conduct),” the use of the term “defendant” in § 5C1.2(2) “limits the accountability of the defendant to his own conduct and conduct that he aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused.” See U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2, comment. (n.4). This language mirrors § 1B1.3(a)(1)(A). Of import is the fact that this language omits the text of § 1B1.3(a)(1)(B) which provides that “relevant conduct” encompasses acts and omissions undertaken in a “jointly undertaken criminal activity,” e.g. a conspiracy.

Being bound by this commentary, we conclude that in determining a defendant’s eligibility for the safety valve, § 5C1.2(2) allows for consideration of only the defendant’s conduct, not the conduct of his co-conspirators. As it was Wilson’s co-conspirator, and not Wilson himself, who possessed the gun in the conspiracy,the district court erred in concluding that Wilson was ineligible to receive the benefit of § 5C1.2. Because application of § 5C1.2 is mandatory, see U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2 (providing that the court “shall” impose a sentencing without regard to the statutory minimum sentence if the defendant satisfies the provision’s criteria), we vacate Wilson’s sentence and remand for resentencing.

The defense must also be able to prove that the defendant’s role in the underlying criminal offense did not result in the death or bodily injury of someone else to achieve the safety valve defense under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f).

In drug cases, this can mean more than some type of violent scenario. The mere type of drug or controlled substance involved can impact the success of this defense. Sometimes, the drugs themselves are the type that can cause severe harm or death. Several controlled substances can be lethal. In a federal drug case, there is a special definition for death resulting from the distribution of a controlled substance.

If the defense can prove with authenticated and admissible evidence that the defendant did not distribute a drug or controlled substance that ended up with someone’s death, or severe bodily injury, then the safety valve defense will be available to them.

Role adjustments happen when someone is alleged to be involved in a conspiracy, and they act in some type of position of responsibility. They can be a leader, or organizer, or somebody who supervises other people in the operations, all as defined in the USSG.

If you are to achieve the safety valve defense, you cannot receive any “role adjustment” under the Sentencing Guidelines. This must be established to the court by your defense attorney at the sentencing.

The defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

I realize that for many people, this language brings with it the assumption that the defendant has to be a snitch in order to meet this requirement for the safety valve defense. This is not true.

With an experienced criminal defense lawyer, what it does mean is that the defendant has a meeting with the authorities with the goal of meeting the Safety Valve Statute requirements and no more.

The attorney can limit the scope of the meeting. He or she can make sure that law enforcement follows the rules for the meeting. The meeting is necessary for the defendant to achieve a safety valve defense, so there is no way to avoid a safety valve interview.

I arranged for my client to have his safety valve meeting as well as establishing the other criteria needed for application of the Safety Valve statute. I was present at the meeting. There was no cooperation regarding the other defendants, and he did nothing more than the minimum to qualify for the defense. He was no snitch.

As a result, the safety valve was applied by the federal judge and my client achieved a safety valve application where he was sentenced to 8 years for distribution of meth: well below the 10 years of the mandatory minimums and the USSG calculation in his case of around 14 years.

Sadly, the same day that my client was sentenced, so were several of the co-conspirator defendants. I was aware that they were also eligible for the safety valve defense. However, the federal agent at the sentencing hearings that day told me that their lawyers never contact the government for a safety valve meeting.

They were never debriefed, so they could not meet the requirements for application of the safety value statute. The judge had no choice –they each had to be sentenced to the mandatory minimum sentences under the law.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

“Mandatory minimum sentences are also unlikely to reduce crime by incapacitation, at least given the overbreadth of such laws and their failure to focus on those most likely to recidivate. Among other things, offenders typically age out of the criminal lifestyle, usually in their 30s, meaning that long mandatory sentences may require the continued incarceration of individuals who would not be engaged in crime. In such cases, the extra years of imprisonment will not incapacitate otherwise active criminals and thus will not result in reduced crime. … Moreover, certain offenses subject to mandatory minimums can draw upon a large supply of potential participants. With drug organizations, for instance, an arrested dealer or courier may be quickly replaced by another, eliminating any crime-reduction benefit. More generally, any incapacitation-based effect from mandatory minimums was likely achieved years ago, due to the diminishing marginal returns of locking more people up in an age of mass incarceration. Based on the foregoing arguments and others, most scholars have rejected crime-control arguments for mandatory sentencing laws. By virtually all measures, there is no reason to believe that mandatory minimums have any meaningful impact on crime rates.”

“The conclusion that increasing already long sentences has no material deterrent effect also has implications for mandatory minimum sentencing. Mandatory minimum sentence statutes have two distinct properties. One is that they typically increase already long sentences, which we have concluded is not an effective deterrent. Second, by mandating incarceration, they also increase the certainty of imprisonment given conviction. Because, as discussed earlier, the certainty of conviction even following commission of a felony is typically small, the effect of mandatory minimum sentencing on certainty of punishment is greatly diminished. Furthermore, as discussed at length by Nagin (2013a, 2013b), all of the evidence on the deterrent effect of certainty of punishment pertains to the deterrent effect of the certainty of apprehension, not to the certainty of postarrest outcomes (including certainty of imprisonment given conviction). Thus, there is no evidence one way or the other on the deterrent effect of the second distinguishing characteristic of mandatory minimum sentencing (Nagin, 2013a, 2013b).”

Tonry, Michael. “Fifty Years of American Sentencing Reform — Nine Lessons.” 7 Dec. 2018, Crime and Justice—A Review of Research. Forthcoming. Available at SSRN:https://ssrn.com/abstract=3297777

“Mandatory Sentences. Mandatory sentencing laws should be repealed, and no new ones enacted; they produce countless injustices, encourage cynical circumventions, and seldom achieve demonstrable reductions in crime.

“Mandatory sentencing laws are a fundamentally bad idea. From eighteenth century England, when pickpockets worked the crowds at hangings of pickpockets and juries refused to convict people of offenses subject to severe punishments, to twenty-first century America, the evidence has been clear. Mandatory minimum sentences have few if any discernible deterrent effects and, because of their rigidity, result in unjustly harsh punishments in many cases and willful circumvention by prosecutors, judges, and juries in others. In our time, when plea bargaining is ubiquitous, mandatories are routinely used to coerce guilty pleas, sometimes from innocent people (Johnson 2019).

‘Knowledge about mandatory minimum sentences has changed remarkably little in the past 30 years. Their ostensible primary rationale is deterrence. The overwhelming weight of the evidence, however, shows that they have few if any deterrent effects … Existing knowledge is too fragmentary [and] estimated effects are so small or contingent on particular circumstances as to have no practical relevance for policy making. (Travis, Western, and Redburn 2014, p. 83)’

“Contemporary research thus confirms longstanding cautions against enactment of mandatory sentencing laws. Their use to coerce guilty pleas is new and distinctive to our times. Even innocent defendants are sorely tempted to plead guilty and accept probation or a short prison term rather than risk a mandatory 10- or 20-year sentence. The late Harvard Law School professor William Stuntz observed that ‘outside the plea-bargaining process’ prosecutors’ threats to file charges subject to mandatories ‘would be deemed extortionate’ (2011, p. 260). Federal Court of Appeals judge Gerald Lynch similarly observed that prosecutors’ power to threaten mandatories has enabled them to displace judges from their traditional role: It is ‘the prosecutor who decides what sentence the defendant should be given in exchange for his plea’ (2003, p. 1404). American sentencing has become more severe in recent decades; prosecutors bear much of the responsibility (Johnson 2019).

“Every authoritative law reform organization that has examined American sentencing in the last 50 years has proposed elimination of mandatory minimum sentence laws. These included, in earlier times, the 1967 President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, the 1971 National Commission on Reform of Federal Laws, the 1973 National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, the 1979 Model Sentencing and Corrections Act proposed by the Uniform Law Commissioners, and the American Bar Association’s 1994 Sentencing Standards. The American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code—Sentencing offered the same recommendation in 2017 (Reitz and Klingele 2019).”

Considerable empirical research has shown that racial disparities in sentencing are pervasive: “one of every nine black men between the ages of twenty and thirty-four is behind bars.” In United States v. Booker, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered the mandatory guidelines merely advisory. This study, looking not just at judicial opinions but also at plea agreements, charging decisions, and other factors contributing to sentencing, shows that this racial disparity has actually not increased since more judicial discretion was permitted. Instead, the black-white gap in sentencing “appears to stem largely from prosecutors’ charging choices, especially to charge defendants with ‘mandatory minimum’ offenses.” Removing these minimums as advisory guidelines would help shift toward greater racial equalization in the sentencing arena.

“Despite substantial expenditures on longer prison terms for drug offenders, taxpayers have not realized a strong public safety return. The self-reported use of illegal drugs has increased over the long term as drug prices have fallen and purity has risen. Federal sentencing laws that were designed with serious traffickers in mind have resulted in lengthy imprisonment of offenders who played relatively minor roles. These laws also have failed to reduce recidivism. Nearly a third of the drug offenders who leave federal prison and are placed on community supervision commit new crimes or violate the conditions of their release—a rate that has not changed substantially in decades.”

8613371530291

8613371530291