safety valve 2-point reduction supplier

Safety Valve is a provision codified in 18 U.S.C. 3553(f), that applies to non-violent, cooperative defendants with minimal criminal record without a leadership enhancement convicted under several federal criminal statutes. Congress created Safety Valve in order to ensure that low-level participants of drug organizations were not disproportionately punished for their conduct.

Generally applying to drug crimes with a mandatory minimum, Safety Valve has two major benefits for individuals charged with those crimes. Specifically, the two benefits of Safety Valve are:

The first benefit of Safety Valve is the ability to receive a sentence below a mandatory minimum on certain types of drug cases. Some drug charges have a mandatory minimum i.e. 5 years, 10 years. That means even if the person’s guidelines are lower than the mandatory minimum and the judge wants the sentence the individual below the mandatory minimum, the judge is legally unable to do so because that would be an illegal plea. If the Court determines that the individual meets the requirements of Safety Valve under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), the Judge is able to sentence the individual to a term that is less than the mandatory minimum.

The second benefit of safety valve is a two-point reduction in total offense conduct. Since 2009, federal sentencing guidelines are discretionary rather than binding. With that being said, federal sentencing guidelines still act as the Judge’s starting point in determining what the appropriate sentence on a case is. The higher the total offense score, the higher is the corresponding suggested sentencing range. A two-level difference can make a difference in months if not years of the sentence. Each point counts toward ensuring the lowest possible sentence.

In order to establish eligibility for Safety Valve, the Defendant has the burden of proof to establish that s/he meets the five requirements by a preponderance of evidence. That is to say, the Defendant must prove by 51% that the Defendant meets all the requirements of eligibility. These five Safety Valve Requirements are explained in greater detail below.

The first requirement of Safety Valve is that the individual has a limited criminal record. The U.S. Sentencing Guidelines assign a certain number of points to prior convictions. The more serious the crime, and the longer the sentence, the more corresponding criminal history points it carries.

The second requirement of Safety Valve is that the individual did not use violence, credible threats of violence or possess a firearm or other dangerous weapon. Importantly, an individual can be disqualified from Safety Valve based on the conduct of co-conspirators, if the Defendant “aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused” the co-conspirator’s violence or possession of a firearm or another dangerous weapon. Thus, use of violence or possession of a weapon by a co-defendant does not disqualify someone from Safety Valve, unless the individual somehow helped or instructed the co-defendant to engage in that conduct.

To be disqualified from Safety Valve, possession of a firearm or another dangerous weapon can either be actual possession or constructive possession. Actual possession involves the individual having the gun in their hand or on their person. Constructive possession means that the individual has control over the place or area where the gun was located. Importantly, the possession of a firearm or a dangerous weapon needs to be related to the drug crime, as the statute requires possession of same “in connection with the offense.” However, “in connection with the offense” is a relatively loose standard, in that presence of the firearm or dangerous instrument in the same location as the drugs is enough to disqualify someone from Safety Valve.

The third requirement of Safety Valve is that the offense conduct did not result in death or serious bodily injury to any person. Serious bodily injury for the purposes of Safety Valve is defined as “injury involving extreme physical pain or the protracted impairment of a function of a bodily member, organ, or mental faculty; or requiring medical intervention such as surgery, hospitalization, or physical rehabilitation.”

The fourth requirement of Safety Valve is that the Defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager or supervisor of others in the office. An individual will be disqualified from safety valve if s/he exercised any supervisory power or control over another participant. Individuals who receive an enhancement for an aggravating role under §3B1.1 are not eligible for safety valve. Similarly, in order to be eligible for Safety Valve, an individual does not need to receive a minor participant role reduction.

The fifth and final Safety Valve requirement is that the individual meet with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for a Safety Valve proffer. A Safety Valve proffer is different from a regular proffer in that in a safety valve proffer, the individual is only required to truthfully proffer about his or her own conduct.

In contrast, in a non-safety valve proffer, the individual is required to truthfully provide information about his or her own criminal conduct, as well as the criminal conduct of others. In order to meet this requirement, the individual must provide a full and complete disclosure about their own criminal conduct, not just the allegations that are charged in the offense. There is no required time as to when someone goes in for a safety valve proffer, except that it must take place sometime “before sentencing.”

Not all charges with mandatory minimums qualify for Safety Valve relief. Rather, the criminal charge must be enumerated in 18 U.S.C. 3553(f). The following criminal charges are eligible for Safety Valve:

Under the First Step Act, the eligibility for Safety Valve relief was expanded to more individuals. Specifically, The First Step Act, P.L. 115-391, broadened the safety valve to provide relief for:

Prior to the enactment of the First Step Act, individuals could have a maximum of 1 criminal history point in order to be eligible for Safety Valve relief. Similarly, individuals who were prosecuted for possession of drugs aboard a vessel under the Maritime Drug Enforcement Act, were not eligible for Safety Valve relief. After the passing of the First Step Act, individuals prosecuted under Maritime Drug Enforcement Act, specifically 46 U.S.C. 70503 or 46 U.S.C. 70506 are eligible for Safety Valve relief.

Safety Valve is an important component of plea negotiations on federal drug cases and should always be explored by experienced federal counsel. If you have questions regarding your Safety Valve eligibility, please contact us today to schedule your consultation.

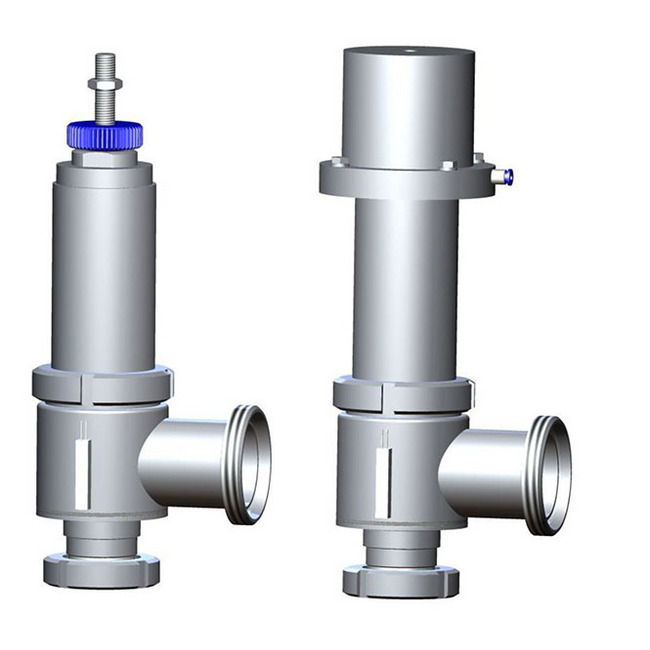

Curtiss-Wright"s selection of Pressure Relief Valves comes from its outstanding product brands Farris and Target Rock. We endeavor to support the whole life cycle of a facility and continuously provide custom products and technologies. Boasting a reputation for producing high quality, durable products, our collection of Pressure Relief Valves is guaranteed to provide effective and reliable pressure relief.

While some basic components and activations in relieving pressure may differ between the specific types of relief valves, each aims to be 100% effective in keeping your equipment running safely. Our current range includes numerous valve types, from flanged to spring-loaded, threaded to wireless, pilot operated, and much more.

A pressure relief valve is a type of safety valve designed to control the pressure in a vessel. It protects the system and keeps the people operating the device safely in an overpressure event or equipment failure.

A pressure relief valve is designed to withstand a maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP). Once an overpressure event occurs in the system, the pressure relief valve detects pressure beyond its design"s specified capability. The pressure relief valve would then discharge the pressurized fluid or gas to flow from an auxiliary passage out of the system.

Below is an example of one of our pilot operated pressure relief valves in action; the cutaway demonstrates when high pressure is released from the system.

Air pressure relief valves can be applied to a variety of environments and equipment. Pressure relief valves are a safety valve used to keep equipment and the operators safe too. They"re instrumental in applications where proper pressure levels are vital for correct and safe operation. Such as oil and gas, power generation like central heating systems, and multi-phase applications in refining and chemical processing.

At Curtiss-Wright, we provide a range of different pressure relief valves based on two primary operations – spring-loaded and pilot operated. Spring-loaded valves can either be conventional spring-loaded or balanced spring-loaded.

Spring-loaded valves are programmed to open and close via a spring mechanism. They open when the pressure reaches an unacceptable level to release the material inside the vessel. It closes automatically when the pressure is released, and it returns to an average operating level. Spring-loaded safety valves rely on the closing force applied by a spring onto the main seating area. They can also be controlled in numerous ways, such as a remote, control panel, and computer program.

Pilot-operated relief valves operate by combining the primary relieving device (main valve) with self-actuated auxiliary pressure relief valves, also known as the pilot control. This pilot control dictates the opening and closing of the main valve and responds to system pressure. System pressure is fed from the inlet into and through the pilot control and ultimately into the main valve"s dome. In normal operating conditions, system pressure will prevent the main valve from opening.

The valves allow media to flow from an auxiliary passage and out of the system once absolute pressure is reached, whether it is a maximum or minimum level.

When the pressure is below the maximum amount, the pressure differential is slightly positive on the piston"s dome size, which keeps the main valve in the closed position. When system pressure rises and reaches the set point, the pilot will cut off flow to the dome, causing depressurization in the piston"s dome side. The pressure differential has reversed, and the piston will rise, opening the main valve, relieving pressure.

When the process pressure decreases to a specific pressure, the pilot closes, the dome is repressurized, and the main valve closes. The main difference between spring-loaded PRVs and pilot-operated is that a pilot-operated safety valve uses pressure to keep the valve closed.

Pilot-operated relief valves are controlled by hand and are typically opened often through a wheel or similar component. The user opens the valve when the gauge signifies that the system pressure is at an unsafe level; once the valve has opened and the pressure has been released, the operator can shut it by hand again.

Increasing pressure helps to maintain the pilot"s seal. Once the setpoint has been reached, the valve opens. This reduces leakage and fugitive emissions.

At set pressure the valve snaps to full lift. This can be quite violent on large pipes with significant pressure. The pressure has to drop below the set pressure in order for the piston to reseat.

At Curtiss-Wright we also provide solutions for pressure relief valve monitoring. Historically, pressure relief valves have been difficult or impossible to monitor. Our SmartPRV features a 2600 Series pressure relief valve accessorized with a wireless position monitor that alerts plant operators during an overpressure event, including the time and duration.

There are many causes of overpressure, but the most common ones are typically blocked discharge in the system, gas blowby, and fire. Even proper inspection and maintenance will not eliminate the occurrence of leakages. An air pressure relief valve is the only way to ensure a safe environment for the device, its surroundings, and operators.

A PRV and PSV are interchangeable, but there is a difference between the two valves. A pressure release valve gradually opens when experiencing pressure, whereas a pressure safety valve opens suddenly when the pressure hits a certain level of over pressurization. Safety valves can be used manually and are typically used for a permanent shutdown. Air pressure relief valves are used for operational requirements, and they gently release the pressure before it hits the maximum high-pressure point and circulates it back into the system.

Pressure relief valves should be subject to an annual test, one per year. The operator is responsible for carrying out the test, which should be done using an air compressor. It’s imperative to ensure pressure relief valves maintain their effectiveness over time and are checked for signs of corrosion and loss of functionality. Air pressure relief valves should also be checked before their installation, after each fire event, and regularly as decided by the operators.

Direct-acting solenoid valves have a direct connection with the opening and closing armature, whereas pilot-operated valves use of the process fluid to assist in piloting the operation of the valve.

A control valve works by varying the rate of fluid passing through the valve itself. As the valve stem moves, it alters the size of the passage and increases, decreases or holds steady the flow. The opening and closing of the valve is altered whenever the controlled process parameter does not reach the set point.

Control valves are usually at floor level or easily accessible via platforms. They are also located on the same equipment or pipeline as the measurement and downstream or flow measurements.

An industrial relief valve is designed to control or limit surges of pressure in a system, most often in fluid or compressed air system valves. It does so as a form of protection for the system and defending against instrument or equipment failure. They are usually present in clean water industries.

A PRV is often referred to as a pressure relief valve, which is also known as a PSV or pressure safety valve. They are used interchangeably throughout the industry depending on company standards.

The pressure below the valve must increase above the set pressurebefore the safety valve reaches a noticeable lift. As a result of the restriction of flow between the disc and the adjusting ring, pressure builds up in the huddling chamber. The pressure now acts on an enlarged disc area. This increases the force Fp so that the additional spring force required to further compress the spring is overcome. The valve will open rapidly with a "pop", in most cases to its full lift.

Overpressure is the pressure increase above the set pressurenecessary for the safety valve to achieve full lift and capacity. The overpressure is usually expressed as a percentage of the set pressure. Codes and standards provide limits for the maximum overpressure. A typical value is 10%, ranging between 3% and 21% depending on the code and application.

In order to ensure that the maximum allowable accumulation pressure of any system or apparatus protected by a safety valve is never exceeded, careful consideration of the safety valve’s position in the system has to be made. As there is such a wide range of applications, there is no absolute rule as to where the valve should be positioned and therefore, every application needs to be treated separately.

A common steam application for a safety valve is to protect process equipment supplied from a pressure reducing station. Two possible arrangements are shown in Figure 9.3.3.

The safety valve can be fitted within the pressure reducing station itself, that is, before the downstream stop valve, as in Figure 9.3.3 (a), or further downstream, nearer the apparatus as in Figure 9.3.3 (b). Fitting the safety valve before the downstream stop valve has the following advantages:

• The safety valve can be tested in-line by shutting down the downstream stop valve without the chance of downstream apparatus being over pressurised, should the safety valve fail under test.

• When setting the PRV under no-load conditions, the operation of the safety valve can be observed, as this condition is most likely to cause ‘simmer’. If this should occur, the PRV pressure can be adjusted to below the safety valve reseat pressure.

Indeed, a separate safety valve may have to be fitted on the inlet to each downstream piece of apparatus, when the PRV supplies several such pieces of apparatus.

• If supplying one piece of apparatus, which has a MAWP pressure less than the PRV supply pressure, the apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve, preferably close-coupled to its steam inlet connection.

• If a PRV is supplying more than one apparatus and the MAWP of any item is less than the PRV supply pressure, either the PRV station must be fitted with a safety valve set at the lowest possible MAWP of the connected apparatus, or each item of affected apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve.

• The safety valve must be located so that the pressure cannot accumulate in the apparatus viaanother route, for example, from a separate steam line or a bypass line.

It could be argued that every installation deserves special consideration when it comes to safety, but the following applications and situations are a little unusual and worth considering:

• Fire - Any pressure vessel should be protected from overpressure in the event of fire. Although a safety valve mounted for operational protection may also offer protection under fire conditions,such cases require special consideration, which is beyond the scope of this text.

• Exothermic applications - These must be fitted with a safety valve close-coupled to the apparatus steam inlet or the body direct. No alternative applies.

• Safety valves used as warning devices - Sometimes, safety valves are fitted to systems as warning devices. They are not required to relieve fault loads but to warn of pressures increasing above normal working pressures for operational reasons only. In these instances, safety valves are set at the warning pressure and only need to be of minimum size. If there is any danger of systems fitted with such a safety valve exceeding their maximum allowable working pressure, they must be protected by additional safety valves in the usual way.

In order to illustrate the importance of the positioning of a safety valve, consider an automatic pump trap (see Block 14) used to remove condensate from a heating vessel. The automatic pump trap (APT), incorporates a mechanical type pump, which uses the motive force of steam to pump the condensate through the return system. The position of the safety valve will depend on the MAWP of the APT and its required motive inlet pressure.

This arrangement is suitable if the pump-trap motive pressure is less than 1.6 bar g (safety valve set pressure of 2 bar g less 0.3 bar blowdown and a 0.1 bar shut-off margin). Since the MAWP of both the APT and the vessel are greater than the safety valve set pressure, a single safety valve would provide suitable protection for the system.

Here, two separate PRV stations are used each with its own safety valve. If the APT internals failed and steam at 4 bar g passed through the APT and into the vessel, safety valve ‘A’ would relieve this pressure and protect the vessel. Safety valve ‘B’ would not lift as the pressure in the APT is still acceptable and below its set pressure.

It should be noted that safety valve ‘A’ is positioned on the downstream side of the temperature control valve; this is done for both safety and operational reasons:

Operation - There is less chance of safety valve ‘A’ simmering during operation in this position,as the pressure is typically lower after the control valve than before it.

Also, note that if the MAWP of the pump-trap were greater than the pressure upstream of PRV ‘A’, it would be permissible to omit safety valve ‘B’ from the system, but safety valve ‘A’ must be sized to take into account the total fault flow through PRV ‘B’ as well as through PRV ‘A’.

A pharmaceutical factory has twelve jacketed pans on the same production floor, all rated with the same MAWP. Where would the safety valve be positioned?

One solution would be to install a safety valve on the inlet to each pan (Figure 9.3.6). In this instance, each safety valve would have to be sized to pass the entire load, in case the PRV failed open whilst the other eleven pans were shut down.

If additional apparatus with a lower MAWP than the pans (for example, a shell and tube heat exchanger) were to be included in the system, it would be necessary to fit an additional safety valve. This safety valve would be set to an appropriate lower set pressure and sized to pass the fault flow through the temperature control valve (see Figure 9.3.8).

R series proportional relief valves provide simple, reliable, overpressure protection for a variety of liquid or gas general-industry applications with set pressures from 10 to 6000 psig (0.7 to 413 bar). They open gradually as the pressure increases and will close when the system pressure falls below the set pressure. The set pressure can be set at the factory or easily adjusted in the field. PRV series proportional safety relief valves are certified to PED 2014/68/EU Category IV, CE-marked in accordance with the Pressure Equipment Directive as a safety valve according to ISO-4126-1, and factory-set, tested, locked, and tagged with the set pressure.

Swagelok bleed valves can be used on instrumentation devices such as multivalve manifolds or gauge valves to vent signal line pressure to atmosphere before removal of an instrument or to assist in calibration of control devices. Male NPT and SAE end connections are available. Purge valves are manual bleed, vent, or drain valves with NPT, SAE, Swagelok tube fitting, or tube adapter end connections. A knurled cap is permanently assembled to the valve body for safety. Both bleed and purge valves are compact for convenient installation.

8th Circuit affirms denial of safety valve where defendant’s debrief was full of inconsistencies. (246) Prior to pleading guilty to drug trafficking, defendant gave an interview to an investigator. His statements had multiple inconsistencies, including his source for the drugs, so the government declined to move for safety valve relief from his ten-year mandatory minimum sentence, under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) and guideline § 5C1.2. The Eighth Circuit affirmed, ruling that the district court properly relied on the investigator’s testimony in denying a safety valve reduction. U.S. v. Trujillo-Linares, __ F.4th __ (8th Cir. Dec. 28, 2021) No. 21-1301.

1st Circuit denies safety valve credit for lack of truthfulness. (246) Defendant pleaded guilty to drug conspiracy with a five-year mandatory minimum. The district court found that she was not eligible for the safety valve in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)(5) because she did not truthfully provide all information about the offense to which she pleaded guilty. The First Circuit affirmed, rejecting defendant’s attempt to characterize her misstatements as “unimportant blunders.” She also failed to explain the information on her cell phone. U.S. v. Martinez, __ F.4th __ (1st Cir. Aug. 13, 2021) No. 19-1667.

11th Circuit finds defendant’s possession of firearm barred safety valve relief. (246) At sentencing for drug trafficking, the district court denied a two-level “safety valve” reduction under § 5C1.2 because defendant possessed a dangerous weapon during the drug trafficking offense. The Eleventh Circuit held that defendant failed to carry his burden to show that it was “clearly improbable” that the firearm was connected to the drug offense. U.S. v. Carrasquillo, __ F.3d __ (11th Cir. July 14, 2021) No. 19-14143.

8th Circuit affirms denial of “safety valve” for failure to truthfully divulge information about offense. (246) Defendant was convicted of drug trafficking. At sentencing, the district court denied her a two-level decrease in her offense level under § 2D1.1(b)(18), for failure to meet the requirements of the “safety valve” in § 5C1.2. The Eighth Circuit affirmed the district court’s finding that defendant had not “truthfully provided” all information about her offense. She said she was unaware what she was trafficking, but the trial evidence refuted that claim. U.S. v. Hernandez, __ F.3d __ (8th Cir. June 9, 2021) No. 20-1343.

1st Circuit says maritime drug trafficking is not subject to safety valve. (246) Defendant pled guilty to drug trafficking on the high seas, in violation of the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act, 46 U.S.C. §§ 70503 & 70506. That offense carries a mandatory minimum. The First Circuit held that the MDLEA is not subject to the “safety valve” in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) and guidelines § 5C1.2, because the MDLEA is not a listed offense. U.S. v. De La Cruz, __ F.3d __ (1st Cir. May 26, 2021) No. 18-1710.

9th Circuit finds “and” in safety valve means “and,” contrary to 11th Circuit. (246) A defendant is eligible for the safety valve in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), if he does not have “(A) more than 4 criminal history points . . . (B) a prior 3-point offense . . . and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense . . .” The government argued that the word “and” was disjunctive and therefore defendant’s prior 3-point vandalism conviction made him ineligible for the safety valve. Ninth Circuit held that the “and” in § 3553(f) is conjunctive, rejecting the government’s position and holding that defendant was eligible for the safety valve because he did not meet all three disqualifying criteria. In U.S. v. Garcon, __ F.3d __ (11th Cir. May 18, 2021) No. 19-14650, the Eleventh Circuit reached the opposite conclusion. U.S. v. Lopez, __ F.3d (9th Cir. May 21, 2021) No. 19-50305.

11th Circuit finds “and” in safety valve means “or,” contrary to 9th Circuit. (246) The safety valve in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) says a defendant is eligible if he does not have “(A) more than 4 criminal history points . . . (B) a prior 3-point offense . . . and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense. . . .” The district court interpreted “and” as conjunctive, and found defendant eligible for the safety valve because he did not have a prior violent offense. The government appealed, and the Eleventh Circuit held that the “and” in § 3553(f) is disjunctive and that defendant was not eligible for the safety valve. In U.S. v. Lopez, __ F.3d (9th Cir. May 21, 2021) No. 19-50305, the Ninth Circuit reached the opposite conclusion. U.S. v. Garcon, __ F.3d __ (11th Cir. May 18, 2021) No. 19-14650.

8th Circuit finds gun transaction barred eligibility for safety valve. (246) Defendant pleaded guilty to drug trafficking with a five-year mandatory minimum sentence. He told law enforcement officers about a firearms transaction he had witnessed, and later testified for the defense at the retrial of a defendant for possession of those firearms. At sentencing, the district court found defendant was lying and therefore not eligible for the safety valve. Defendant argued that the firearms transaction was unrelated and should not have been considered. The Eighth Circuit agreed with the district court that the firearms transaction and the drug trafficking were part of a common scheme or plan, and thus he was not eligible for the safety valve. U.S. v. McVay, __ F.3d __ (8th Cir. May 6, 2021) No. 20-1169.

8th Circuit denies safety valve where defendant was not truthful. (246) Defendant arranged a 20-pound methamphetamine deal and pleaded guilty to conspiracy to distribute at least 50 grams of methamphetamine. After her arrest, defendant gave a proffer in which she said the methamphetamine deal was her first involvement in drug trafficking. At sentencing, the government argued that defendant was not eligible for the safety valve because she had lied during her proffer. The undercover agent testified that defendant had acted as if she were running the deal and used coded language in calls to other conspirators. The district court denied safety valve credit under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) and § 5C1.2(a), and the Eighth Circuit affirmed, finding it was reasonable for the district court to conclude that defendant was not being honest in her proffer. U.S. v. Rios, __ F.3d __ (8th Cir. Apr. 28, 2021) No. 20-1146.

11th Circuit says safety valve does not apply to Title 46 offenses, so no Fifth Amendment issue. (120)(246) Defendants were convicted at trial of transporting cocaine on the high seas in violation of 46 U.S.C. § 70506. Defendants argued that by forcing them to tell about their offense, the “safety valve” statute violated their Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. The Eleventh Circuit held that because Title 46 offenses are not eligible for the safety valve, it was unnecessary to address that concern. U.S. v. Cabezas-Montana, __ F.3d __ (11th Cir. Jan. 30, 2020) No. 17-14294.

11th Circuit upholds denying “safety valve” where defendant failed to disclose all drug deliveries. (246) At sentencing for possessing more than 500 grams of methamphetamine with intent to distribute, defendant sought a “safety valve” reduction under §§ 2D1.1(b)(17) and 5C1.2(a), arguing that he had answered all the government’s questions, provided information about the persons with whom he had conspired, and disclosed the identity of another person involved in the drug trafficking even though the government did not ask. The government opposed the reduction with evidence that defendant did not provide complete information about one of his coconspirators and failed to admit that he delivered drugs to the informant even though there was evidence of more deliveries. The district court denied the reduction, and the Eleventh Circuit affirmed. The court found that the government had adequately supported its claim that defendant had not disclosed all of the drug deliveries he made to the informant. U.S. v. Mancilla-Ibarra, __ F.3d __ (11th Cir. Jan. 15, 2020) No. 17-13663.

6th Circuit finds defendant eligible for safety valve despite codefendant’s firearm possession. (246) Defendant was subject to a mandatory minimum drug sentence. The district court found he did not qualify for a reduction under the “safety valve” in § 5C1.2 and 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), because he possessed a firearm in connection with his offense and because he did not truthfully provide all information about the offense. The Sixth Circuit reversed, holding that the fact that defendant could foresee a codefendant’s possession of a firearm did not preclude application of the “safety valve,” and that defendant’s failure to provide an explanation of a large amount of money found with the drugs in his room did not disqualify him from obtaining a sentence below the mandatory minimum. U.S. v. Barron, __ F.3d __ (6th Cir. Oct. 15, 2019) No. 18-5222.

7th Circuit says judge, not jury, finds facts relating to safety-valve eligibility. (120)(246) Defendant pleaded guilty to drug trafficking. The district court denied a safety-valve reduction from the mandatory five-year minimum sentence because defendant’s DNA was found on a firearm recovered from his residence and therefore defendant was not eligible for the safety valve. On appeal, defendant argued that the Jury Clause of the Sixth Amendment barred the district court from finding that he could not obtain the safety valve because he possessed the firearm in connection with the drug-trafficking offense. The Seventh Circuit held that the Sixth Amendment does not bar judicial fact-finding of safety-valve eligibility. U.S. v. Fincher, __ F.3d __ (7th Cir. July 9, 2019) No. 18-2520.

1st Circuit allows court to withhold safety valve from eligible defendant. (246) Defendant pleaded guilty to drug-trafficking. Although he faced a minimum mandatory sentence of 120 months, he was eligible for the safety valve in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f). As a result, his sentencing range was 108 to 135 months. Nevertheless, The district court declined to apply the safety valve and instead sentenced him to 135 months. The First Circuit held that it is not unreasonable to sentence a defendant eligible for the safety valve to a sentence above the mandatory minimum. U.S. v. Reyes-Gomez, __ F.3d __ (1st Cir. June 11, 2019) No. 17-1757.

7th Circuit denies safety valve where defendant was not truthful. (246) Law enforcement agents arrested defendant in his car with $40,000. A confidential source said that defendant was going to use the money to buy a kilogram of cocaine. Defendant pleaded guilty to drug trafficking and was subject to a mandatory minimum ten-year sentence. Defendant sought the safety valve in 18 U.S.C § 3553(f). One requirement for the safety valve is that a defendant “truthfully provide” all information about his offense. In a post-arrest interview, defendant said that the $40,000 was to buy a nice car. He denied any intent to purchase cocaine. After an evidentiary hearing, the district court found that defendant had not been truthful and denied a safety valve reduction. The Seventh Circuit held that defendant had not carried his burden of establishing eligibility for the safety valve. U.S. v. Collins, __ F.3d __ (7th Cir. May 14, 2019) No. 18-2149.

11th Circuit says “safety valve’s” exclusion of international drug traffickers does not violate equal protection. (120)(246) Under the “safety valve” in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) and § 5C1.2, a defendant convicted of a Title 21 offense can receive a sentence under the mandatory minimum. However, defendant was convicted of drug trafficking in international waters under the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act in Title 46, which is not listed in the “safety valve.” Defendant claimed that there was no rational basis to exclude Title 46 defendants from obtaining the safety valve and therefore that exclusion violated the Equal Protection Clause. The Eleventh Circuit found that Congress had legitimate reasons for excluding international drug traffickers from the safety valve and did not violate the Clause. U.S. v. Valois, __ F.3d __ (11th Cir. Feb. 12, 2019) No. 17-13535.

10th Circuit denies safety valve where firearms may have facilitated the offense. (246) When defendant was arrested for drug trafficking in a truck in a rural area, he possessed two loaded firearms which he admitted belonged to him. He was convicted of drug trafficking. At sentencing, the district court found that defendant was not eligible for the safety valve under § 5C1.2 because of the proximity of the firearms and their potential to facilitate the offense. On appeal, the Tenth Circuit affirmed, rejecting defendant’s argument that he did not possess the firearms in connection with the offense. The panel agreed that defendant’s possession of the firearms had the potential to facilitate the offense. U.S. v. Hargrove, __ F.3d __ (10th Cir. Jan. 2, 2019) No. 17-2102.

5th Circuit finds challenge to criminal history is not reviewable as plain error. (246)(870) Defendant was convicted of drug trafficking. For the first time on appeal, he argued that the district court’s improper calculation of his criminal history made him ineligible for a “safety valve” reduction below the mandatory minimum, under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f). The Fifth Circuit found no plain error, because defendant would not have been eligible for the “safety valve” regardless, because he had a criminal history point for a conviction defendant did not challenge. U.S. v. Cordell, __ F.3d __ (5th Cir. Oct. 19, 2018) No. 17-30937.

5th Circuit holds safety valve does not apply to violations of 46 U.S.C. § 70503. (246) Defendant pleaded guilty to conspiracy to possess cocaine with intent to distribute, while aboard a vessel subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, in violation of 46 U.S.C. §§ 70503(a)(1), 70506(a) & (b) and 21 U.S.C. § 960. The district court denied defendant safety valve relief, finding that the safety valve provision applies only to the five offenses specified in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), and 46 U.S.C. § 70503 was not one of those offenses. The Fifth Circuit agreed. As a general matter this court has strictly limited the safety valve’s application to the statutes listed in § 3553(f). Although 21 U.S.C. § 960, which provides the penalties for § 70503, was enumerated in § 3553(f), § 70503 was not an “offense under” § 960; § 960 merely provided the penalties for § 70503. The court relied on U.S. v. Pertuz-Pertuz, 679 F.3d 1327 (11th Cir. 2012); U.S. v. Gamboa-Cardenas, 508 F.3d 491 (9th Cir. 2007) to hold that the safety valve does not apply to violations of § 70503. U.S. v. Anchundia-Espinoza, __ F.3d __ (5th Cir. July 27, 2018) No. 17-40584.

5th Circuit holds that defendant waived safety valve claim. (246)(855) Defendant pled guilty to drug charges. At sentencing, the court noted that without a role enhancement, defendant might be eligible for a safety valve reduction. The government explained that it could not make a safety valve request “right now” because defendant’s debrief had been cut short. The district court asked defendant if he would like more time to possibly qualify for the reduction. After conferring with counsel, defendant declined, and sought, instead, to proceed with sentencing. Defendant acknowledged that this meant that he would not qualify for either a safety-valve reduction or a §5K1.1 downward departure. The district court imposed a within-guideline sentence of 78 months. Nonetheless, defendant argued on appeal that the district court erred by not applying the safety valve reduction under §2D1.1(b)(17). The Fifth Circuit held that defendant waived his claim that court erred by not granting safety valve relief. U.S. v. Rodriguez-De la Fuente, 842 F.3d 371 (5th Cir. 2016).

8th Circuit says facts used to deny safety valve relief need not be proved to jury. (120)(246) The district court found defendant was not eligible for safety valve relief under 18 U.S.C. §3553(f) because he possessed firearms in connection with his drug offense, and therefore the court imposed a mandatory minimum 120-month sentence under 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A). The Supreme Court in Alleyne v. U.S., __ U.S. __, 133 S. Ct. 2151 (2013), held that any fact that establishes or increases a mandatory minimum sentence must be submitted to the jury and found beyond a reasonable doubt. The Eighth Circuit rejected defendant’s argument that Alleyne requires the government to prove that he possessed a firearm beyond a reasonable doubt. Facts that make a defendant ineligible for the safety valve do not create or increase a mandatory minimum—the safety valve simply allows for relieffrom a mandatory minimum in certain circumstances. U.S. v. Leanos, __ F.3d __ (8th Cir. July 11, 2016) No. 15-3248.

8th Circuit agrees that defendant possessed firearm and thus was not eligible for safety valve. (246) Defendant pled guilty to drug and firearm charges, and received a mandatory minimum 120-month sentence under 21 U.S.C. §841(B)(1)(A). The Eighth Circuit upheld the district court’s finding that defendant possessed a firearm in connection with the offense, and thus was not eligible for safety valve relief. Officers discovered the firearms in the house with the drugs, and defendant admitted buying one firearm from a drug dealer for personal protection. Defendant stipulated in his plea agreement that he possessed the two firearms and ammunition in the home. Also, he admitted that he purchased one of the firearms from a drug dealer for his own protection. Finally, defendant distributed drugs out of that house. U.S. v. Leanos, __ F.3d __ (8th Cir. July 11, 2016) No. 15-3248.

7th Circuit denies safety valve relief based on defendant’s statements during interview. (246) Defendant was convicted of drug charges and was sentenced to a mandatory minimum 120 months. During a safety valve interview, he claimed that he had never dealt drugs before, but needed money for his catering business, so he helped a confidential informant (the CI) find a supplier. After the interview, the government explained that it did not believe that a newcomer to the drug trade, without a reputation for trustworthiness, could broker a six-kilogram cocaine transaction. The district court refused to grant safety valve relief because it was unpersuaded that defendant spoke truthfully in his interview. The district court pointed to inconsistent and implausible statements, including that defendant did not know that he was aiding in a drug deal when he drove to the CI’s ranch; defendant’s use of a pseudonym when he first contacted the CI; and defendant’s assertion that he had never been a drug dealer before. The Seventh Circuit upheld the denial of safety valve relief, sharing the district court’s disbelief in defendant’s story. U.S. v. Rebolledo-Delgadillo, __ F.3d __ (7th Cir. Apr. 28, 2016) No. 15-2121.

8th Circuit says defendant did not show that she was entitled to safety valve relief. (246) Defendant argued for the first time on appeal that the district court erred in failing to provide her with safety valve relief. The Eighth Circuit found no plain error, ruling that defendant did not meet her burden of establishing that she qualified for safety valve relief. She could not establish that she ever truthfully provided the government with all information she had about the charged offense. Besides a brief interaction with a trooper during a traffic stop when the drugs were found, defendant never provided additional information to the government. Accordingly, district court did not plainly err in failing to grant defendant safety valve relief. U.S. v. Morales, __ F.3d __ (8th Cir. Feb. 10, 2016) No. 15-1630.

3rd Circuit finds ineffective assistance for improper advice about safety valve. (245)(246)(880) Defendant pled guilty to distributing or manufacturing drugs near a school, in violation of 21 U.S.C. § 860(a). He later claimed that he pled guilty because counsel advised him that he was eligible for a reduced sentence pursuant to the “safety valve.” In a pro se habeas petition, defendant argued that his counsel’s erroneous advice about the safety valve constituted ineffective assistance. The Third Circuit agreed. The record clearly indicated that defendant’s counsel provided him with incorrect advice regarding the availability of the safety valve sentencing reduction in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f). In fact, counsel filed a motion for a reduction, but at sentencing, counsel withdrew this motion, because U.S. v. McQuilkin, 78 F.3d 105 (3d Cir.1996) held that § 3553(f) did not apply to convictions under 21 U.S.C. § 860. Counsel’s lack of familiarity with an 18-year-old precedent and his erroneous advice, demonstrated performance below prevailing professional norms. The plea colloquy did not remedy counsel’s mistake, since the judge made several statements that reinforced counsel’s incorrect advice. Defendant also showed that but for counsel’s error, he would not have pled guilty and insisted on going to trial. U.S. v. Bui, __ F.3d __ (3d Cir. Aug. 4, 2015) No. 11-3795.

7th Circuit denies safety valve relief based on co-conspirators’ gun possession. (246) Defendant received a §2D1.1(b)(1) enhancement based on her co-conspirators’ possession of a firearms. Possession of a firearm generally disqualifies a defendant from safety-valve protection. See §5C1.2(a)(2). Defendant argued for the first time on appeal that her receipt of the firearm enhancement did not disqualify her from receiving safety-valve relief because she neither possessed a gun herself nor induced another to do so. Other circuits have concluded that the scope of the safety-valve’s “no firearms” condition is narrower than the firearms enhancement, and does not impute responsibility for the acts of co-conspirators. Nonetheless, the Seventh Circuit held that the district court’s refusal to grant defendant safety valve relief was not plain error. Defendant raised a question of first impression in the circuit, and courts rarely find plain error on a matter of first impression. Given the lack of guiding circuit precedent, the district court could not be faulted for failing to raise and apply the safety valve sua sponte. U.S. v. Ramirez, __ F.3d __ (7th Cir. Apr. 15, 2015) No. 13-1013.

10th Circuit requires court to consider safety valve information provided for first time on remand. (246) Defendant was convicted of drug charges. He successfully appealed, and the case was remanded for resentencing. At resentencing, the district court denied his request for safety valve protection, holding that 18 U.S.C. §3553(f) did not apply because defendant failed to make the disclosures to support a reduced sentence before his initial sentencing hearing. The Tenth Circuit held that when a defendant provides information to the government for the first time on remand, but before the resentencing hearing, the plain text of §3553(f) requires the district court to consider that information. The district court interpreted the statute’s requirement that the defendant provide information “not later than the time of the sentencing hearing,” to exclude disclosures made before a resentencing hearing. However, this phrase clearly and unambiguously referred to “the sentencing hearing” at issue, whether it was an initial, second, or subsequent sentencing hearing. Nothing in the text of §3553(f)(5) suggested that the phrase, “not later than the time of the sentencing hearing,” should be read to include an extra word—”not later than the time of the initial sentencing hearing.” U.S. v. Figueroa-Labrada, __ F.3d __ (10th Cir. Mar. 24, 2015) No. 13-6278.

7th Circuit denies safety valve relief where defendant did not tell all and threatened informant. (246) Defendant argued that his cooperation with law enforcement after his arrest qualified him for “safety valve” relief from the statutory minimum. See 18 U.S.C. §3553(f); U.S.S.G. §5C1.2. A DEA agent testified that the information defendant provided after his arrest was helpful, and defendant maintained that he had no additional information about the offense. However, the district court found that defendant’s cooperation was not a full and truthful proffer. The Seventh Circuit upheld the denial of safety valve credit, finding the district court gave a nuanced explanation of why it found that defendant not tell all information he knew. Moreover, defendant did not assist the investigation during the two years that passed between his initial post-arrest statements and his sentencing, which undermined his assertion of full, good faith cooperation. There was also evidence that defendant threatened death to the informant and his family, which disqualified him from safety-valve relief. U.S. v. Ortiz, __ F.3d __ (7th Cir. Jan. 12, 2015) No. 13-3748.

1st Circuit says safety valve requirements are mandatory despite Booker. (246) Defendant argued that the district court erred in concluding that it had no authority to sentence him below the mandatory minimum sentence because he did not satisfy all of the safety valve factors in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f). He argued that because the safety-valve requirements reference the Guidelines and Booker made the Guidelines advisory, then the safety valve requirements were also advisory. The First Circuit noted that this argument has been rejected by all the courts of appeals that have considered it. U.S. v. Zayas, 568 F.3d 43 (1st Cir. 2009).

1st Circuit says prior drug trafficking was relevant conduct or “safety valve” was improper. (246) Defendant pled guilty to conspiring to transport cocaine in two separate criminal cases. One case involved 20 kilos of sham cocaine that defendant received from a cooperating agent. The other case arose from 30 kilos of cocaine that defendant and his crew placed on an airplane bound for New York. He pled guilty and was sentenced first for his role in the sham cocaine smuggling scheme. At the second proceeding, the court declined to consider the sham cocaine as relevant conduct in calculating the total quantity of drugs, and found that he was eligible for the “safety valve” in §5C1.2 as a first offender. The First Circuit reversed, noting that unless the prior sham cocaine offense were included as relevant conduct in the second offense, his prior conviction would count as more than one criminal history point; making him ineligible for the “safety valve.” U.S. v. Jaca-Nazario, 521 F.3d 50 (1st Cir. 2008).

1st Circuit holds that court did not have discretion to reduce criminal history points in order to make defendant eligible for safety value relief. (246) Defendant received a 10-year mandatory minimum sentence following his guilty plea to drug charges, in violation of 21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1). Defendant contended that his sentence should be vacated because the district court erroneously believed it lacked discretion to qualify defendant for safety valve protection, 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), by lowering defendant’s criminal history category to I. The First Circuit held that the criminal history calculation for purposes of safety valve eligibility is non-discretionary. The court properly found that it was unable to reduce his criminal history score to make him eligible for safety valve protection. Booker did not change this analysis. As other circuits have held, Booker did not excise and render advisory the requirement of § 3553(f) that a defendant have zero or one criminal history points in order to qualify for safety valve relief. U.S. v. Hunt, 503 F.3d 34 (1st Cir. 2007).

1st Circuit denies safety valve based on testimony of experienced agent that drug smugglers must have been aware of drugs. (246) Defendants were crew members of a boat smuggling drugs into the U.S. The district court refused to grant them safety valve protection. The First Circuit reversed as to the first defendant, since the court failed to make even conclusory statements as to why he did not merit safety-valve relief. At the other two defendants’ joint hearing, however, the court credited the testimony of a special government agent that these defendants had not disclosed everything they knew about the drug smuggling conspiracy. It was “illogical” and “incredible” to believe that an international drug smuggler would place $7.5 million of drugs on a vessel traveling in international waters without having some type of voluntary control over the vessel’s crew. This testimony, based on the agent’s years of experience in the field of drug interdiction, provided a sound grounding for the court’s denial of the safety valve. U.S. v. Bravo, 489 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2007).

1st Circuit upholds finding that defendants had not truthfully provided information about offense. (246) The Coast Guard arrested defendants in a fishing vessel containing 5,000 pounds of marijuana. At trial, defendants testified that they had been recruited to participate in a fishing expedition and that when they learned that the boat actually contained marijuana, they were forced at gun point to serve as its crew. A jury rejected this defense and convicted defendants of possession with intent to distribute marijuana and of conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute marijuana. At sentencing, the district court credited the testimony of a federal law enforcement agent that defendants’ story was illogical and incredible. Based on the agent’s testimony, the court found that defendants had not truthfully provided the government with all information concerning the offense and denied them a safety valve reduction. The First Circuit held that the district court did not clearly err in finding that defendants had not met the safety valve requirement that they truthfully provide all information concerning their offense. U.S. v. Bravo, 480 F.3d 88 (1st Cir. 2007).

1st Circuit holds that finding that defendant was eligible for safety valve reduction did not preclude firearm enhancement. (246) The district court applied a two-level sentencing enhancement for firearm possession under § 2D1.1(b)(1), since defendant acknowledged that police had found a loaded handgun in his apartment, and that defendant stated that he bought the gun for personal protection. The court also applied a two-level reduction under the “safety valve” provision of U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2, despite its requirement that the defendant show that he was not in possession of a firearm. The First Circuit found nothing contradictory about applying both the firearm enhancement and the safety valve reduction, since different standards apply for each. The application of the safety valve requires the defendant to establish by a preponderance of the evidence that he did not possess the firearm in connection with the offense. For the firearm enhancement, the government has the initial burden of establishing that a firearm possessed by the defendant was present during the commission of the offense. After that, the burden shifts to defendant to persuade the court that a connection between the weapon and the crime is clearly improbable. Defendant’s failure to meet the higher burden of proof required for the firearm enhancement did not preclude the defendant from meeting the lower burden of proof in the safety valve provision. U.S. v. Anderson, 452 F.3d 87 (1st Cir. 2006).

1st Circuit holds that Booker does not give court authority to disregard criminal history to make defendant eligible for safety valve. (246) Defendant’s plea agreement provided that if defendant met “all” of the requirements of the “safety valve” of U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2, he would receive a two-level reduction under § 2D1.1(b) (6). The First Circuit agreed that defendant was not entitled to safety value relief because he did not meet all of the requirements – he had three criminal history points. The panel rejected defendant’s argument that the court had the discretion to disregard the criminal history computation called for under the guidelines. Even if this argument were not foreclosed by defendant’s stipulation in the plea agreement that his sentence would be determined according to the guidelines, his argument failed as a matter of law because there can be no Bookererror where a defendant is sentenced to a statutory minimum based on admitted facts. Booker does not give a court discretion to disregard an otherwise applicable statutory minimum. U.S. v. Narvaez-Rosario, 440 F.3d 50 (1st Cir. 2006).

1st Circuit says finding that defendant did not establish safety valve entitlement was not subject to Booker challenge. (246) The district court found that defendant was not entitled to safety valve protection under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) (2) and § 2D1.1(b)(7). Defendant argued that the court violated the Sixth Amendment by crediting evidence that the police found 11 firearms in defendant’s apartment during their execution of a search warrant. The First Circuit held that this safety valve finding need not be decided by a jury or admitted by the defendant under Booker. The burden of proof rests with the defendant to establish an entitlement to safety valve protection. The district court’s finding that defendant failed to establish that he did not possess a firearm in connection with the offense of conviction was not subject to a Bookerchallenge. U.S. v. Morrisette, 429 F.3d 318 (1st Cir. 2005).

1st Circuit holds that Booker did not entitle defendant to resentencing so that he could comply with safety valve. (246) Defendant sought resentencing on the ground that the Sixth Amendment required the facts determining compliance with the safety valve to be found by a jury rather than by a judge. Because he did not understand that requirement when he decided not to participate in the safety valve regimen, defendant argued that he would have made a different decision if he had known that his entitlement to a sentence reduction would have to be found by a jury by a reasonable doubt. The First Circuit rejected this claim. A change in the law does not warrant vacating a sentence so that the defendant may reconsider his initial decision not to pursue a safety valve reduction, just as a change in the law does not warrant vacating a guilty plea so that the defendant may choose to face trial instead. Defendant was not entitled to resentencing under Booker, because he did not preserve his Booker claim and failed to demonstrate a reasonable probability of a lower sentence under an advisory guideline regime. U.S. v. De Los Santos, 420 F.3d 10 (1st Cir. 2005).

1st Circuit finds insufficient evidence of constructive possession of hidden firearm. (246) The district court found that defendants were ineligible for safety valve protection under § 5C1.2 because they each possessed a .22 caliber handgun during the course of the conspiracy. Defendants argued that proof of actual possession was required to bar application of the safety valve, and even if constructive possession was sufficient, there was inadequate evidence to establish such possession. The First Circuit held that a defendant who has constructively possessed a firearm in connection with a drug trafficking offense is ineligible for the safety valve provisions in § 5C1.2. However, there was insufficient evidence here that two of the defendants constructively possessed the gun. As to the first defendant, he did not stay in the room where the weapon was found. The fact that he was aware that his co-conspirators were interested in 9 mm pistols was not sufficient evidence that defendant knew that his co-conspirators had actually acquired a .22 caliber pistol. Although the second defendant stayed in the room where the gun was found, there was inadequate evidence to infer that he had actual knowledge of the gun. The fact that he participated in drug transactions in his room while the handgun was hidden in the closet was not enough to show knowledge of the hidden gun. U.S. v. McLean, 409 F.3d 492 (1st Cir. 2005).

1st Circuit holds that safety valve amendment could not be applied retroactively. (246) Defendant moved to modify his sentence, arguing that Amendment 640 to the Sentencing Guidelines, effective November 1, 2002, applied retroactively to his case and authorized the court to reduce his sentence by using the safety valve adjustment. The First Circuit held that Amendment 640 was a substantive amendment and therefore, was not to be applied retroactively. The amendment is substantive – its principal effect is to create a new offense level cap for safety valve purposes. The amendment also is not listed in USSG § 1B1.10(c) as one to be given retroactive effect. U.S. v. Cabrera-Polo, 376 F.3d 29 (1st Cir. 2004).

1st Circuit holds safety valve is not barred by weapon enhancement based on co-conspirator liability. (246) Defendant’s offense level was increased under § 2D1.1(b)(1) because “a dangerous weapon … was possessed” during the course of the offense. Under U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2, a defendant is eligible for safety valve reduction if he meets certain criteria, including the requirement that he “did not use violence or credible threats of violence of possess a firearm or other dangerous weapon” in connection with the offense. Five circuits have held that application of § 5C1.2 is not precluded by a weapons possession enhancement based on co-conspirator liability. See, e.g. U.S. v. Penn-Sarabia, 297 F.3d 983 (10th Cir. 2002). The First Circuit agreed that in order for the safety valve to be precluded, a defendant must possess or induce another to possess a firearm in accordance with § 5C1.2(a) (2). Since the basis for the court’s denial of safety valve protection was unclear, the case was remanded for resentencing. U.S. v. Figueroa-Encarnacion, 343 F.3d 23 (1st Cir. 2003).

1st Circuit upholds finding that defendants did not meet information requirement of safety valve. (246) Defendants contended that they met the full disclosure requirement of the safety valve provision, asserting that they had truthfully and completely answered all the questions that the government had asked, and therefore, that the burden had shifted to the government to show that they were ineligible for the safety valve. They further contended that if the government believed that either of them was withholding information, it had a duty to come forward with the basis for that belief so that the affected defendant would have a fair chance to explain away the alleged omission. The First Circuit upheld the court’s finding that defendants did not satisfy the disclosure requirements of the safety valve provision. First, a defendant bears the burden of showing that he made appropriate and timely disclosures to the government. Although defendants insisted they filled any gaps in their original disclosures by their testimony during sentencing, such disclosures must be made by the time the sentencing hearing starts. 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)(5). Moreover, the provision requires a defendant to be forthcoming. He cannot simply respond to questions while at the same time keeping secret pertinent information that falls beyond the scope of direct interrogation.. Finally, the panel rejected the suggestion that the government acted in bad faith because it would not tell defendants, early on, why it believed that they were not telling the whole truth. “If the government reasonably suspects that the defendant is being devious, it is not obliged to tip its hand as to what other information it may have so that the defendant may shape his disclosures to cover his tracks, minimize his involvement, or protect his confederates.” U.S. v. Matos, 328 F.3d 34 (1st Cir. 2003).

1st Circuit says court was not required to examine applicability of safety-valve before accepting plea. (246) Defendant argued that, pursuant to Rule 11(f), the district court should have inquired into the applicability of the safety-valve provision before accepting his guilty plea. The First Circuit disagreed, and found that the district court’s dialogue satisfied Rule 11(f). Whether or not defendant used or threatened to use a firearm (the conduct which made him ineligible for the safety valve), was not a necessary part of the substantive offense. Although defendant contended that he did not understand at the time of his plea that he could be sentenced beyond the 87-108 month term mentioned in the plea agreement, the agreement stated at the outset that the statutory penalty for Count I was not less than ten years and not more than life, and the court expressly asked defendant whether he understood this penalty. Further, after addressing the sentencing range set forth in the plea agreement, the court inquired if defendant understood that “it’s up to the Judge to decide if that is correct, and it can go up or down, including the ten-year minimum and life sentence.” Again, defendant said he understood. The court did not provide inaccurate sentencing information. Any confusion of defendant about the potential length of his sentence was not the result of having been incorrectly advised by the court during the Rule 11 plea colloquy. U.S. v. Ramirez-Be

8613371530291

8613371530291