is safety valve snitching manufacturer

In federal cases, Congress not only defines what is a crime that can cost the accused both freedom and property, but it also passes statutes that control how federal judges are allowed to sentence those who have been convicted of federal drug crimes. For instance, federal judges must follow the United States Sentencing Guidelines when sentencing someone upon conviction of a federal crime. For more on sentencing guidelines and how they work, read our discussion in Federal Sentencing Guidelines: Conspiracy To Distribute Controlled Substance Cases.

Sometimes, Congress sets a bottom line on the number of years someone must spend behind bars upon conviction for a specific federal crime. The federal judge in these situations has no discretion: he or she must follow the Congressional mandate.

Of course, there are a tremendous number of federal laws that define federal drug crimes. For purposes of illustration, consider those federal drug crimes that come with either (1) a sentence of 10 years to life imprisonment or (2) those that come with a sentence of 5 to 40 years behind bars, both defined as the mandatory sentences to be given upon conviction for these defined federal drug crimes.

For reference, these refer to the statutory language of 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A) and 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B), which instruct the federal judge on how he or she shall sentence anyone convicted of the manufacture, distribution, or dispensing of a controlled substance (i.e., an illegal drug) or possession with intent to either of these things.

Key here: the judge is given the mandatory minimum number of years that the accused must spend behind bars by Congress via the federal statutory language. A federal judge cannot go below ten (10) years for a federal drug crime based upon 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A). He or she cannot go below five (5) years for a federal drug crime conviction based upon 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B).

Can’t there be any way to get around that set-in-stone bottom line? Yes. There is also a statutory exception which allows the federal judge to dip below that mandatory minimum number of years in some situations. It is called the “Safety Valve” defense.

The law, 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), provides for an exception that allows the federal judge some leeway in drug crime convictions where he or she would otherwise be required to follow the mandatory minimum sentencing statute. This is the Safety Value statute. It states as follows:

(f)Limitation on Applicability of Statutory Minimums in Certain Cases.—Notwithstanding anyother provision of law, in the case of an offense under section 401, 404, or 406 of theControlled Substances Act(21 U.S.C. 841, 844, 846), section 1010 or 1013 of theControlled Substances Import and Export Act(21 U.S.C. 960, 963), or section 70503 or 70506 of title 46, the court shall impose a sentence pursuant to guidelines promulgated by the United States Sentencing Commission undersection 994 of title 28without regard to any statutory minimum sentence, if the court finds at sentencing, after the Government has been afforded the opportunity to make a recommendation, that—

(A)more than 4 criminal history points, excluding any criminal history points resulting from a 1-point offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines;

(4)the defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager, or supervisor of others in the offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise, as defined in section 408 of theControlled Substances Act; and

(5)not later than the time of the sentencing hearing, the defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

Information disclosed by a defendant under this subsection may not be used to enhance the sentence of the defendant unless the information relates to aviolent offense.

The only way to allow for this exception to be applied in a federal sentencing hearing is for the defense to argue its application and to provide authenticated and admissible support for use of the Safety Valve.

How does the defense do this? It takes much more than referencing the exception to the general rule itself. The defense will have to demonstrate the convicted defendant meets the Safety Valve’s five (5) requirements.

Federal sentencing has its own reference manual that is used throughout the United States, called the United States Sentencing Guidelines (“USSG”). We have gone into detail about the USSG and its applications in earlier discussions; to learn more, read:

In short, the idea is that the USSG work to keep things fair for people being sentenced in federal courts no matter which state they are located. Someone convicted in Texas, for instance, should be able to receive the same or similar treatment in a federal sentencing hearing as someone in Alaska, Maine, or Hawaii.

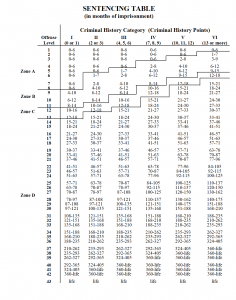

Part of how the Sentencing Guidelines work is by assessing “points.” Offenses are given points. The points tally into a score that is calculated according to the USSG.

Essentially, the accused can be charged with a three-point offense; a two-point offense; or a one-point offense. The number of points will depend on things like if it is a violent crime; violent crimes get more points than non-violent ones. The higher the overall number of points, and the ultimate total score, then the longer the sentence to be given under the USSG.

For a successful safety valve defense, the defense has to show that the total Criminal History Points are four (4) or less. If you have a maximum of four Criminal History points, you have met the first criteria for the safety valve.

Note: prior to the passage of the First Step Act, things were much harsher. If the defense had even two Criminal History Points, then the accused was ineligible for the safety valve. The First Step Act increased the number of points, or score, from one to four as the maximum allowed for application of the safety valve. For more on the First Step Act, see The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 1 of 2 and The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 2 of 2.

Looking at the Safety Valve statute ( 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)), the second step in achieving application of the safety valve defense involves the circumstances of the underlying criminal activity and whether or not it involved violence of threats or violence, or if the defendant possessed a firearm at the time.

It has been my experience that it is pretty common for there to be a firearm of some sort involved in a federal drug crime prosecution. Here, the impact of Texas being a part of the Fifth Judicial District for the United States Court of Appeals (“Fifth Circuit”) is important.

This is because this overseeing federal appeals court has looked at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) and its definition of possession of a firearm, and come to a different conclusion that the definition given in the USSG.

Meanwhile, the Fifth Circuit has ruled that under the Safety Valve Statute, the standard for the government is much higher. According to their ruling, in order to be disqualified from application of the safety valve because of possession of a firearm, the defendant has to have been actually in possession of the firearm or in construction possession of it. See, US v. Wilson, 105 F.3d 219 (5th Cir. 1997).

Consider how this works in a federal drug crime conspiracy case. Under the USSG, a defendant can receive two (2) points (“enhancement”) for possession of a firearm even if they never had their hands on the gun. As long as a co-conspirator (co-defendant) did have possession of it, and that possession was foreseeable by the defendant, then the Sentencing Guidelines allow for a harsher sentence (more points).

The position of the Fifth Circuit looks upon this situation and determines that it is one thing for the defendant to have possession of the firearm, and another for there to be stretching things to cover constructive possession when he or she never really had the gun.

This is the example of the importance of effective criminal defense representation, where research reveals that it is easier to achieve a safety valve defense with a reference to case law. The Fifth Circuit allows a situation where someone can get two (2) points under the USSG (“enhancement”) and still be eligible for the safety valve defense.

The commentary to § 5C1.2(2) provides that “[c]onsistent with [U.S.S.G.] § 1B1.3 (Relevant Conduct),” the use of the term “defendant” in § 5C1.2(2) “limits the accountability of the defendant to his own conduct and conduct that he aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused.” See U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2, comment. (n.4). This language mirrors § 1B1.3(a)(1)(A). Of import is the fact that this language omits the text of § 1B1.3(a)(1)(B) which provides that “relevant conduct” encompasses acts and omissions undertaken in a “jointly undertaken criminal activity,” e.g. a conspiracy.

Being bound by this commentary, we conclude that in determining a defendant’s eligibility for the safety valve, § 5C1.2(2) allows for consideration of only the defendant’s conduct, not the conduct of his co-conspirators. As it was Wilson’s co-conspirator, and not Wilson himself, who possessed the gun in the conspiracy,the district court erred in concluding that Wilson was ineligible to receive the benefit of § 5C1.2. Because application of § 5C1.2 is mandatory, see U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2 (providing that the court “shall” impose a sentencing without regard to the statutory minimum sentence if the defendant satisfies the provision’s criteria), we vacate Wilson’s sentence and remand for resentencing.

The defense must also be able to prove that the defendant’s role in the underlying criminal offense did not result in the death or bodily injury of someone else to achieve the safety valve defense under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f).

In drug cases, this can mean more than some type of violent scenario. The mere type of drug or controlled substance involved can impact the success of this defense. Sometimes, the drugs themselves are the type that can cause severe harm or death. Several controlled substances can be lethal. In a federal drug case, there is a special definition for death resulting from the distribution of a controlled substance.

If the defense can prove with authenticated and admissible evidence that the defendant did not distribute a drug or controlled substance that ended up with someone’s death, or severe bodily injury, then the safety valve defense will be available to them.

Role adjustments happen when someone is alleged to be involved in a conspiracy, and they act in some type of position of responsibility. They can be a leader, or organizer, or somebody who supervises other people in the operations, all as defined in the USSG.

If you are to achieve the safety valve defense, you cannot receive any “role adjustment” under the Sentencing Guidelines. This must be established to the court by your defense attorney at the sentencing.

The defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

I realize that for many people, this language brings with it the assumption that the defendant has to be a snitch in order to meet this requirement for the safety valve defense. This is not true.

This law does not require a defendant to cooperate against other people in a conspiracy, be it friends or family members or anyone else. It does not force a defendant to turn over new or additional evidence to the police or prosecutors so the government can use it against other defendants. It does not mean the defendant has to cooperate with the government to help them go after unindicted co-conspirators, either.

With an experienced criminal defense lawyer, what it does mean is that the defendant has a meeting with the authorities with the goal of meeting the Safety Valve Statute requirements and no more.

The attorney can limit the scope of the meeting. He or she can make sure that law enforcement follows the rules for the meeting. The meeting is necessary for the defendant to achieve a safety valve defense, so there is no way to avoid a safety valve interview.

To get the sentence that is below the mandatory minimum sentence, the meeting is a must. However, it is not a free-for-all for the government where the defendant is ratting on other people.

One example involves a case where I represented a client before the federal district court in Corpus Christi, the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas. He was among several co-defendants charged in a conspiracy to distribute methamphetamine.

I arranged for my client to have his safety valve meeting as well as establishing the other criteria needed for application of the Safety Valve statute. I was present at the meeting. There was no cooperation regarding the other defendants, and he did nothing more than the minimum to qualify for the defense. He was no snitch.

As a result, the safety valve was applied by the federal judge and my client achieved a safety valve application where he was sentenced to 8 years for distribution of meth: well below the 10 years of the mandatory minimums and the USSG calculation in his case of around 14 years.

Sadly, the same day that my client was sentenced, so were several of the co-conspirator defendants. I was aware that they were also eligible for the safety valve defense. However, the federal agent at the sentencing hearings that day told me that their lawyers never contact the government for a safety valve meeting.

They were never debriefed, so they could not meet the requirements for application of the safety value statute. The judge had no choice –they each had to be sentenced to the mandatory minimum sentences under the law.

As every criminal defense lawyer knows, there are some very draconian minimum mandatory sentences in Federal criminal court. There are federal minimum mandatory sentences for certain drug offenses, firearm offenses, and for defendants who have certain convictions. There are two ways to break the minimum mandatory sentence, which then allows a judge to sentence you below the minimum mandatory. The first is called “substantial assistance.” Basically, if you snitch and the government wants your information, uses your information, and they determine that it was worthy of a sentence below the minimum mandatory, they can file a substantial assistant motion and if granted by the judge, the minimum mandatory would no longer apply. You can only get less than the minimum mandatory sentence if the prosecutor files the motion. If they decide not to file the motion, the judge must sentence you to the minimum mandatory sentence up to the maximum sentence. But what if you don’t want to snitch? What if you don’t have any information that the government is interested in? There is one more option that will allow the judge to sentence you below the minimum mandatory sentence: Safety Valve.

The “Safety Valve” provision is a provision of law codified in 18 United States Code §3553(f). It specifically allows a judge to sentence you below the minimum mandatory required by law. However, you must be eligible. There is also a two level reduction in the sentencing guidelines under United States Sentencing Guidelines §2D1.1(b)(17).

A common requirement that disqualifies people is the prior criminal record requirement. Basically, anything other than a minor one time conviction will disqualify you. However, old convictions may not count and some minor convictions also do not count. There is a whole section in federal sentencing guidelines manual that addresses which prior convictions count and how many points are assessed.

In order to get safety valve, you, through your criminal defense attorney, must contact the prosecuting attorney before your sentencing hearing, and tell them that you want to provide them with a statement. You must be willing to tell them everything you know about the offense, who else was involved, and you must be forthcoming and truthful. It will be up to the judge to determine whether you meet this requirement. You should not wait until the last minute either, as the prosecutor has no duty to take your statement within a short period of time before the sentencing hearing and the judge has no duty to continue your sentencing hearing to give you time to provide the government with a statement.

One difference between Safety Valve and Substantial Assistance is that there is no requirement for you to cooperate against anyone else. So, once your provide the information to the prosecutor, you should become eligible to seek safety valve at your sentencing, without having to cooperate against anyone else.

If you are not convicted under one of these statutes, there is no Safety Valve option. For example, Safety Valve is not an option for someone convicted under the Aggravated Identity Theft statute that carries a 2 year minimum mandatory sentence consecutive to any underlying sentence. Similarly, if you were convicted of similar conduct to those eligible for safety valve, but were convicted under a statute not listed above, you still would not be safety valve eligible. For example, if you were convicted fo possession with intent to distribute cocaine while aboard a vessel subject to United States jurisdiction in violation of 46 U.S.C. app. §1903(a), you would not be eligible for safety valve, even though someone convicted of the same conduct on land would be eligible.

After graduation, Mr. Lasnetski accepted a position as a prosecutor at the State Attorney’s Office in Jacksonville. During the next 6 1/2 years as a prosecutor, Mr. Lasnetski tried more than 50 criminal trials, including more than 40 felony trials. He was promoted in 2007 to Division Chief of the Repeat Offender Unit. Mr. Lasnetski was also a full time member of the Homicide Prosecution Team. In 2008, Mr. Lasnetski formed the Law Office of Lasnetski Gihon Law and began defending citizens in criminal court. He represents clients in both State and Federal criminal courts.

Thus is the case with the federal Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 (“SRA”), passed with strong bipartisan support during the Reagan presidency after many years of debate and study. The first indicator that the SRA was not about “reform” was that it was born out of the omnibus Comprehensive Crime Control Act which was designed to overhaul the federal criminal justice system. Notwithstanding that SRA was the afterbirth of a sweeping congressional effort to “get tough” on crime, proponents of SRA hailed its primary purposes which were: “(1) to establish comprehensive and coordinated statutory authority for sentencing [currently found in 18 U.S.C. § 3553]; (2) to address the seemingly intractable problem of unwarranted sentencing disparity and enhance crime control by creating an independent, expert sentencing commission to devise and update periodically a system of mandatory sentencing guidelines; and (3) principally through the sentencing commission to create a means of assembling and distributing sentencing data, coordinating sentence research and education, and generally advancing the state of knowledge about criminal behavior.”

One of the SRA’s chief sponsors, the late Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, believed the U.S. Sentencing Commission (“Commission”) and the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines (“Guidelines”) the Commission would promulgate would accomplish three primary policy goals: 1) produce just punishment, deterrence, incapacitation and rehabilitation; 2) provide certainty and fairness by eliminating the sentencing disparity, which had plagued the federal court system, through individualized sentencing that considered both aggravating and mitigating factors; and 3) enhance the knowledge of human behavior as it pertained to the criminal justice system.

Last year, the Commission issued a report based upon independent analysis and research,Demographic Differences in Federal Sentencing Practices: An Update of the Booker Report’s Multivariate Regression Analysis, which made the following findings:

Black male offenders received longer sentences than white male offenders. The differences in the sentence length have steadily increased since Booker [a 2005 U.S. Supreme Court decision which held the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines are “advisory” and not mandatory as they had been uniformly interpreted since SRA’s enactment].

Female offenders of all races received shorter sentences than male offenders. The difference in sentence length fluctuated at different rates in the time periods studied for white females, black females, Hispanic females, and “other” female offenders (such as those of Native American, Alaskan Native, and Asian or Pacific Islander origin).

Thus, thirty-six years after SRA’s enactment, federal sentencing practices are just as arbitrary, discriminatory, and counterproductive to the goals of justice as they were before SRA’s enactment. This has been especially true in federal sentencing practices in drug cases, most notably those involving crack/powder cocaine. Besides the individual biases of some federal judges in these cases, the primary problem is the mandatory minimum sentence requirements in most drug cases.

Mandatory minimum sentencing was created by Congress in 1986, two years after the enactment of SRA. The Drug Policy Alliance (“DPA”) points out that mandatory drug sentences are based on three factors: type of drug, weight of the drug mixture (or alleged weight in conspiracy cases), and the number of prior convictions. The purpose of mandatory minimums was to target “drug kingpins” but, as DPA notes, the U.S. Sentencing Commission has found that only 5.5 percent of the crack cocaine cases and 11 percent of all federal drug cases involve “high-level drug dealers.”

In 1994, in another futile effort to eliminate the ever-increasing disparity between the “least culpable” and “more culpable” drug offenders, Congress enacted more “sentencing reform” legislation. This time it was the Mandatory Minimum Sentencing Reform Act, codified in § 3553(f), which created a “safety valve” in the Guidelines. The District of Columbia Court of Appeals in In Sealed Case (Sentencing Guidelines “Safety Valve”) in 1997 said the “safety valve” provisions ofU.S.S.G. § 5C1.2 requires U.S. district court judges to disregard mandatory minimums in certain drug cases and instead sentence a defendant pursuant to the Guidelines when he/she satisfies five indices of reduced culpability: “1) the defendant has no more than one criminal history point; 2) the defendant ‘did not use violence or credible threats of violence or possess a firearm or other dangerous weapon (or induce another participant to do so) in connection with the offense’; 3) the offense did not result in death or serious bodily injury; 4) the defendant was not a leader or organizer of the offense; and 5) the defendant has fully cooperated with the government.”

The defendant must satisfy all five indices to warrant a “safety valve” departure from a mandatory minimum sentence. In 2008 the Families Against Mandatory Minimums (“FAMM”) found that since 1995 more than 63,272 federal drug offenders received the benefit of a “safety valve” sentence, which saved the federal government $25,000 per year, shaved off each offender. FAMM touts the benefits of federal “safety valve” provisions as follows:

Give courts flexibility to prevent unjust sentences: safety valves allow courts – in very narrow circumstances – to sentence a defendant below the mandatory minimum if the mandatory minimum is too lengthy or doesn’t fit the offender or the crime.

Protect public safety: safety valves don’t mean that people get off without any prison time, just that they don’t get any more prison time than they deserve. Safety valves thus help 1) prevent prison overcrowding, 2) avoid the need to release violent offenders early to make room for nonviolent offenders entering the system, and 3) save scarce space and resources for those who are a real threat to the community.

Save taxpayers money: when courts sentence offenders below the mandatory minimum, they spend less time in prison than they would otherwise be required to, which results in less corrections costs for taxpayers.

FAMM, however, advocates that the “safety valve” provisions not only be expanded for all drug offenders but extended to all federal offenses mandating a mandatory minimum. The advocacy group points out that the current “safety valve” provisions are so strict that many nonviolent, low-level drug offenders cannot satisfy its five indices. The group notes that in 2008 while 52 percent of all drug offenders had little or no criminal history and 80 percent of them did not have or use a weapon and only 5.7 percent were considered leaders, managers or supervisors of others, only 25 percent of the drug offenders benefitted from the safety valve provisions.

The Commission disputes these FAMM conclusions. In a March 2009 report titled “Impact of Prior Minor Offenses on Eligibility for Safety Valve,” the Commission reported:

“As part of its ongoing review and amendment of the guidelines, the commission, in August 2006, began to examine various aspects of the criminal history rules located in Chapter Four of the guidelines, including the treatment of misdemeanor and petty offenses (minor offenses). The Commission hosted two roundtable discussions on November 1, 2006 and November 3, 2006, in Washington, D.C., to solicit input from judges, defense attorneys, probation officers, Department of Justice representatives, and members of academia as one component of this review. The Commission also gathered information through its training programs, the public comment process, and comments received during a public hearing held in March 2007.

“During the process, some commentators hypothesized that the inclusion of minor offenses in the criminal history calculation has an unwarranted adverse impact on offenders’ criminal history scores and, ultimately, their guideline ranges and sentences. In April 2007, the Commission promulgated an amendment to respond to these concerns and modify the provisions determining whether and when certain minor offenses are counted in the criminal history score.

“The dialogue leadings to the promulgation of the amendment focused, in part, on the frequency with which prior minor offenses caused a defendant convicted of drug trafficking to become ineligible to receive the benefit of the safety valve relief provided by statute and guideline. Data reviewed by the Commission in connection with the amendment showed that relatively few drug trafficking offenders are excluded from receiving the safety valve because of the guideline provision regarding minor offenses.”

In support of this conclusion, the Commission said it examined 24,483 drug offenders, and that 9,115 of them (37.2 percent) received the benefit of the safety valve provisions. Of the 9,115 safety valve beneficiaries, 1,519 of the offenders had a prior “minor offense” in their criminal history which did not affect their safety valve eligibility. Further, the Commission pointed out that of the 15,368 drug trafficking offenders who did not qualify for safety valve consideration, only 788 of them had a prior “minor offense” in their criminal history but who did not qualify because they failed to satisfy all five of the safety valve indices.

Whether the percentage of drug offenders who receive safety valve consideration is 25 percent as stated by FAMM or 37 percent as stated by the Commission is relatively immaterial. The issue, we feel, is that the safety valve considerations are much too stringent to achieve meaningful sentencing reform. When less one-third of the offenders receive the benefit of a “reform” sentencing statute, then it cannot reasonably be said that the desired reform is truly meaningful.

We feel that only two of the five safety valve indices are relevant to meaningful reform objectives: whether a weapon was possessed or used during the offense; and whether the offense resulted in the death or serious bodily injury of anyone.

We would like to stress that we find it particularly offensive that a fundamental aspect of the safety valve statute is that the defendant must become a full-fledged “snitch” to secure the benefit, not only against himself but anyone else who may have been involved, no matter how remote, in any criminal activity associated with the offense. Failure to fully and completely “snitch” is a sufficient basis for the Government to oppose a safety valve benefit and for the court not to extend it.

Finally, we have not only become disillusioned with the Guidelines, even if they are now “advisory,” as a sentencing reform device but have become convinced they will never produce the fair and impartial justice they were designed to achieve in the federal sentencing process. While we are not prepared to return to unfettered judicial discretion in sentencing, we are now convinced that the Guidelines, regardless of how many times they are amended, are unworkable in producing equal, racially neutral sentencing practices in the federal courts.

The Guidelines, no matter their original intent, have not led to any meaningful reform. The result of years of Guideline sentencing has been much less about than justice and fairness in sentencing than about treating individuals as generic automatons, who have no personal and unique histories, backgrounds or accomplishments. The Guidelines have been, and continue to be, used to force defendants to plea guilty and cooperate with the Government or face a severe and draconian sentencing regime. The Guidelines have been used to pressure defendants to accept plea agreements rather than exercise their right to trial by jury, for fear they will lose downward sentencing adjustments for “acceptance of responsibility” and saving the government time preparing for trial. The Guidelines have led to a justice system dependent upon snitches, in which questionable cases are prosecuted by a Government, which understands the immense pressure place upon a defendant to plea guilty, regardless of meritorious defenses the defendant may have or the reality of actual innocence. This is not the American way…

There is a lot written about federal sentencing and safety valves. What follows is a very brief overview of the federal safety valve available to those charged with certain drug offenses.

The safety valve is one of the ways you can get sentenced to less than the mandatory minimum. The law for the safety valve is codified under 18 USC § 3553(f). To qualify for the safety valve you need to meet all of the following criteria:You are with a charged a narcotics offense under of 21 U.S.C. §§ 841, 844, 846, 960, and/or 963

You have no more than one actual criminal history point. In other words, if the court agrees to “look the other way” in an attempt to get you down to one criminal history point, that won’t work. It needs to be no more than one actual criminal history point.

The Government is not alleging a “major role” under the USSG nor is the offense part of a “continuing criminal enterprise” (don’t worry if you’re charged with conspiracy under 21 U.S.C. § 841, that’s not the same as “continuing criminal enterprise” which is charged under 21 U.S.C. § 848.

You agree to give the Government a “full and truthful disclosure” about everything relating to your involvement in the offense. This usually means signing a limited immunity agreement. Sitting down your lawyer, the prosecutors, and the case agents, and telling them everything about your involvement in the case. It does not matter if your cooperation is helpful or even substantial.

It depends. Under USSG § 4A1.2(c), the following offenses do not count towards your criminal history unless you were sentenced to more than one year probation or served more than 30 days in jail:Reckless driving or careless driving

And the following offenses never count towards your criminal history, no matter what your sentence is:Juvenile “status offenses” like truancy or curfew violations

Yes, that’s right. United States v. Booker 543 U.S 220 (2005), made the United States Sentencing Guidelines advisory. That means the guidelines are now only one of several factors the judge must consider consider at sentencing. Unfortunately, Booker did nothing to alter the laws regarding mandatory minimums. The mandatory minimums are still in place, which is why safety valve is so important if you’re facing a mandatory minimum sentence.

Speak to a California lawyer today if you are facing criminal charges. This is all very general information about safety valve sentencing. If you want to talk further about your particular case, feel free to contact me at (323) 633-3423 or send a message via the secure contact form on this page to schedule a free and confidential consultation.

Over the years I have been retained by a few criminal defense clients after they had bad experience with a prior lawyer. The reasons for switching defense attorneys in midstream vary: sometimes it is concern over the lawyer’s competence, or concern that their case is not getting the attention it deserves, or even that they just don’t see eye to eye with their lawyer. One of the most common, and disturbing reasons though is that the client feels that their prior attorney ripped them off. These complaints generally involve “flat-fee” retainer agreements in which a lawyer and a client agree upon a fixed sum of money for the entire defense representation no matter whether it goes to trial or ends in a plea deal. I see cases all the time where a lawyer accepts a major felony case for a ridiculously low flat-fee just to land the client. Then, when it becomes obvious the case will require a lot of work, the attorney hits the client up for more money. I have even seen cases where the attorney threatens to withdraw from the case if the client does not come up with the additional funds. I call these “pump and dumps:” The lawyer pumps the client for a quick cash infusion and if the client balks, the lawyer tries to dump the client or the retainer agreement. When this happens, the client rightfully becomes upset and the situation quickly becomes untenable. What should a client do? They have (or should have) a written and enforceable fee agreement with the attorney. Then again, who wants a lawyer defending them from serious criminal charges when they claim they are being paid for their work? Defending clients charged with serious or complex felony cases in state and federal courts takes a great amount of work on the part of the criminal defense attorney, the client, and the defense team. These cases are expensive. To get an idea of how expensive, ask the attorney what their normal hourly fee is. The ask them how many hours they would expect to work in a case such as yours. What if it is a plea? What if it is a trial? If the lawyer’s retainer agreement sounds too good to be true, it probably is. The best thing a person can do when selecting a criminal defense attorney is to deal very clearly with this issue up-front. Hourly fee agreements will avoid the problem altogether. The attorney is paid only for the work performed. When negotiating an hourly fee agreement with a criminal defense attorney, be sure to ask the attorney to give a good faith estimate of the number of hours she or he thinks the case will consume depending on various outcomes like a plea agreement or a trial. If you are negotiating a flat-flee agreement make sure that both parties understand that regardless of how many hours the attorney must spend on the case, the fee agreement spells out the total amount to be paid in attorney fees. To protect both parties, flat fee agreements can be modified to suit the needs of each case. For example: The amount of the fee could be staggered to depend on at what stage of the proceedings the case is resolved: Pre-Indictment, with a plea agreement, after a trial etc. Regardless of the attorney and the fee structure you choose. I always recommend the potential client talk to as many knowledgeable and experienced criminal defense attorneys as the situation allows before settling on their pick. This will give the prospective client some idea of comparable fee agreements and rates. It will also allow both parties to get to know each other a little bit before signing up to work so closely together over so serious a matter. Switching attorneys in the middle of the case is sometimes unavoidable, but it is a situation best-avoided if possible.

Many federal criminal defense attorneys are not aware of the pitfalls of the federal safety valve provisions. Persons charged with federal drug crimes need to retain an experienced criminal attorney familiar with all aspects of federal criminal law. An inexperienced or unknowing lawyer can expose a client to catastrophic risks. Here is why.

As we are all keenly aware, the federal government’s “war on drugs” is ensnaring hundreds of people with little or no criminal records who are caught up, for a myriad of reasons, with the distribution of drugs. This can range from a person carrying cash for a friend to pay for an airline ticket, to delivering a package to another person in exchange for cash to pay the rent or feed a child. Because of very harsh federal sentencing laws, the smallest players in a drug ring often end up being the most harshly treated. Most of time this is because the leaders of drug operations very often end up cooperating against others – including those below them whose “loyalty” they often gained through fear and threats of harm. Oftentimes, those persons caught on the lowest rungs of a drug conspiracy find themselves with few alternatives because they do not have significant information to provide to federal prosecutors, who retain exclusive control over who gets cooperation departures under the federal sentencing guidelines. As a result, defendants with minor or minimal culpability in a drug operation frequently end up on the receiving end of prosecutions involving tremendously high sentencing guidelines and, more critically, large minimum mandatory sentences.

In many situations, the only relief from mandatory sentences for those with little or no criminal history is the so-called “safety valve.” Many lawyers talk about the safety valve, but very few understand what it is and what it truly entails. It is perhaps the most misunderstood and most difficult opportunity for relief from mandatory minimum sentences and the sentencing guidelines. Federal crimes lawyers who do not specialize in federal criminal defense work run the risk of harming their clients through misguided efforts to gain relief under the safety valve provision.

It is critical to remember that there are only two ways to avoid minimum mandatory sentences upon conviction for a drug trafficking or drug conspiracy offense in federal court. One way is to cooperate with law enforcement and provide “substantial assistance” in the prosecution of others under section 5K1.1 of the guidelines. The other is to seek relief under the safety valve — Section 5C1.2 of the federal sentencing guidelines. (18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)) This section allows a judge to reduce federal sentencing guidelines and ignore mandatory minimum sentences in determining punishment for eligible defendants.

But while understanding the possible benefits of relief under the safety valve is easy, becoming eligible for the relief is more difficult and fraught with peril for the unwary defendant. In fact, a failed attempt to gain “safety valve” relief can have a tremendously negative impact on a federal criminal defendant.

Section 5C1.2 allows guideline reduction and relief from mandatory minimum sentences when 1) a defendant ‘s criminal history is one point or less under the guidelines, and 2) the defendant truthfully discloses before sentencing everything the defendant knows about his own actions and those who participated in the crime with him. While a defendant is not required to testify in court or become a cooperator, the section does requires that he sit down with federal agents and prosecutors and tell them everything he knows about the charged crime. While a defendant won’t be a witness against others in his case, he still must tell on them. Government agents can affirmatively use the defendant’s information against others in the case without any limitation.

For example, if the defendant tells agents that he stored drugs in his brother’s house, agents can use that information to get a search warrant and raid that house for evidence, even though the defendant would never want his brother to be harmed. Moreover, because the defendant would not be a “cooperator,” prosecutors would be free to name him in their search warrant applications and make no effort to hide the source of their information.

Talking to the government in the context of a safety valve interview can potentially expose the client to consequences worse than those faced by cooperating witnesses.

Next, the attorney has to be 100% certain that the client is telling everything he knows and is not holding back information about himself or others. This requires that attorney be sure of what the government knows in the case before allowing a client to meet for a safety valve interview. If the government thinks that the client is lying, they can make the safety valve process impossible by telling the court about their impressions. If the government can prove the client is lying, then a court is free to increase a client’s sentence for obstruction of justice. Even worse, a client may also lose guideline point reductions for accepting responsibility for the offense and become subject to harsh mandatory minimum sentences.

A defense attorney has to know what the evidence the government has before allowing his client to even think about the safety valve. Anything less can expose the client to catastrophic risk.

The bottom line is that defendants considering a “safety valve” reduction had better have counsel who is experienced in federal criminal law and the pitfalls of federal criminal statutes – even those designed to help defendants. Before becoming a defense attorney, I spent almost a decade prosecuting federal criminal cases in U.S. District Court in Maryland. If you have any questions, contact Federal defense attorney Andrew C. White at Silverman, Thompson, Slutkin & White. There is no situation with which we are not familiar.

If you are charged with a crime by the United States Department of Justice, you may be facing a mandatory minimum sentence, especially if you were arrested on federal drug charges or federal gun charges. However, you may be eligible for the safety valve provision which can significantly reduce your sentence. To learn more about the safety valve provision, along with the strict guidelines for qualifying, Bill Finn, a Raleigh federal lawyer, is sharing what you need to know.

Mandatory minimum sentences are set by Congress, rather than passed down by a judge. If an individual is found guilty of specific crimes or their plea bargain is accepted, they will automatically receive at least the minimum sentence stated by the law.

For example, if you are convicted of drug trafficking 100 grams or more of heroin (but less than one kilogram), your mandatory minimum sentence is five years. However, if death or serious injury results from your actions, the mandatory minimum sentence is increased to 20 years.

The Safety Valve Provision is outlined in 18 U.S. Code § 3553 (f) and was passed by Congress as part of the Sentencing Reform Act in 1984. This was designed to ensure that disproportionate sentences were not given to nonviolent, “low level” offenders with little to no criminal history. The Safety Valve is typically applied to drug crimes with a mandatory minimum, allowing a judge to reduce the sentence less than what is required in the U.S. Code.

In addition to the lighter sentence, the Safety Valve offers a two-point reduction in the total offense. Every federal crime has an “offense level” rated between one and 43, with the higher numbers representing more serious crimes or crimes with compounded factors. For example, if an offender obstructs justice during the investigation, the offense level is increased by two levels, whereas if they clearly accept responsibility for their actions, their offense level may be lowered by two levels.

For those who are eligible for the Safety Valve Provision, the reduction of two offense points can significantly reduce their sentence by months or even years.

Limited Criminal History:The U.S. Code’s sentencing guidelines have specific points assigned to prior convictions. More serious crimes have higher numbers of criminal history points. The defendant can’t have more than four criminal history points not including any 1-point offenses.

No Violence, Credible Threat, or Dangerous Weapon:This was a nonviolent crime, the defendant did not make any credible threats of violence, and they didn’t have a firearm or dangerous weapon. Also, the Court will look at whether the defendant aided, counseled, procured, or caused any co-conspirators to commit violence or possess a firearm during the crime.

Did Not Organize or Lead Others:The defendant can not be the leader, organizer, or manager of a group committing the offense. For example, if the defendant exhibited any type of control over another individual in relation to the offense, they are disqualified from receiving the Safety Valve Provision.

The only applicable charges are those outlined in 18 U.S.C. 3553(f). This includes, but is not limited to: Distribution, manufacturing, or dispensing of a controlled or counterfeit substance (21 U.S. Code § 841)

If you are facing federal criminal charges, you need an experienced attorney on your side to help you secure the best practical outcome in your case. We represent clients in the Eastern District of North Carolina, including Raleigh, Fayetteville, Greenville, and Goldsboro. Reach out to Sandman, Finn & Fitzhugh today at (919) 887-8040 to schedule a free initial consultation, or fill out the form below to get started.

The devil is in the details is a truism, and certainly true of the Senate’s sentencing reform law. That it’s bipartisan, a word rarely used in the past two decades, conveys a special meaning to advocates: this is the best you’re gonna get, as your champions of reform have surrendered to Chuck Grassley. Take it or leave it.

And indeed, advocates of sentencing reform, such as FAMM, know when they’ve been beaten, and so they’re lining up behind this bill. We’re not privy to their kitchen table talks, but it’s impossible to imagine they don’t realize that this is a mutt. Still, a mutt is better than a dog that’s dead on arrival. Those are the compromises advocates tend to make.

The New York Times, unsurprisingly, has given its blessing to this mutt bill, and in the process, has demonstrated yet again that it has no clue what’s in there.Among the most significant are those that would reduce mandatory-minimum sentences for many drug crimes.

“Even small changes can make a real difference” belongs in a fortune cookie. At best, they are “minor tweaks to pointlessly long sentences.” When a sentence that ran ten years before the Sentencing Guidelines was bumped up to life, and now, provided certain conditions be met that few prisoners (except the mythical low-level, non-violent first-offender) could possibly meet, gets, potentially, a few years off the back end, it’s nothing to write home about. How many will die in prison waiting for that backend reward to come?In addition, the bill would give federal judges more power to impose sentences below the mandatory minimum in certain cases, rather than being forced to apply a strict formula. This would shift some power away from prosecutors, who coax plea deals in more than 97 percent of cases, often by threatening defendants with outrageously long punishments.

But this is the most cynical, most misleading, of the “reforms.” What it refers to is Section 103 of the bill:Section 103. Creates a Second Safety Valve that Preserves but Targets the 10-Year Mandatory Minimum to Certain Drug Offenders. A second safety valve is created that preserves but targets the existing 10-year mandatory minimum to (1) offenders who performed an enhanced role in the offense or (2) otherwise served as an importer, exporter, high-level distributor or supplier, wholesaler, or manufacturer. Consistent with the existing safety valve, the offender must not have used violence or a firearm or been a member of a continuing criminal enterprise, and the offense must not have resulted in death or serious bodily injury. The defendant must also truthfully “proffer” with the government and provide any and all information and evidence the defendant has about the offense. This provision also excludes offenders with prior serious drug or serious violent convictions or offenders who distributed drugs to or with a person under the age of 18. This provision is not retroactive.

Under the existing Safety Valve, a low-level defendant is required to “proffer” in order to get out from under the mandatory minimum. The word “proffer” is a euphemism for rat out his co-defendants. The difference is that the defendant wouldn’t be subject to “enhancements” for his role in the offense or prior convictions.

This law doesn’t eliminate the ten year mandatory minimum. It creates a new path for the government to coerce snitching from people who wouldn’t snitch before.

Yet, the Times, and almost all commenters, believe that “this would shift some power away from prosecutors, who coax plea deals.” On the contrary, it extends the prosecutor’s power to coerce snitching.

But doesn’t this reform have a significant benefit for many? Won’t it go a long way in reducing our national shame of mass incarceration?In particular, 6,500 prisoners are still serving time under an old law that punished crack-cocaine offenses far more severely than powder-cocaine offenses.

As of today, there are 205,795 prisoners in federal custody. While the 6,500 estimate of prisoners who might benefit is quite rosy, since a significant percentage has other charges, such as “use and carry” of a weapon, that preclude any benefit, let’s accept that number for the sake of argument.

That means a grand total of 3.16% of federal prisoners may be able to get a sentence reduction. Not a big sentence reduction, but a reduction. They won’t be coming home anytime soon. And that’s for a law that was so insanely misguided in the first instance, a 100 to 1 disparity for crack versus powdered cocaine, that no rational nation should have ever used it in the first place.

Some will find no problem in turning every defendant into a coerced snitch. After all, we’ve spent so much time adoring the mythical “good guy” prisoner, and consequently despising the real defendants for whom life plus cancer is good enough, our national mindset is that the bad dudes should rot in hell forever and no one will shed a tear.

If you focus only on the wrongfully convicted or the low-level, non-violent first-offender, and ignore the reality that these are not the people filling our prisons with sentences of forever, maybe this reform doesn’t strike you as too meaningless.

But after the party is over, what we will be left with is pretty much the same mass incarceration we have now, the same outrageously long sentences that find no rational justification anywhere, and a whole new crop of potential snitches to facilitate the government’s putting more people in prison.

A “safety valve” is an exception to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. A safety valve allows a judge to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum term if certain conditions are met. Safety valves can be broad or narrow, applying to many or few crimes (e.g., drug crimes only) or types of offenders (e.g., nonviolent offenders). They do not repeal or eliminate mandatory minimum sentences. However, safety valves save taxpayers money because they allow courts to give shorter, more appropriate prison sentences to offenders who pose less of a public safety threat. This saves our scarce taxpayer dollars and prison beds for those who are most deserving of the mandatory minimum term and present the biggest danger to society.

The Problem:Under current federal law, there is only one safety valve, and it applies only to first-time, nonviolent drug offenders whose cases did not involve guns. FAMM was instrumental in the passage of this safety valve, in 1994. Since then, more than 95,000 nonviolent drug offenders have received fairer sentences because of it, saving taxpayers billions. But it is a very narrow exception: in FY 2015, only 13 percent of all drug offenders qualified for the exception.

Mere presence of even a lawfully purchased and registered gun in a person’s home or car is enough to disqualify a nonviolent drug offender from the safety valve,

Even very minor prior infractions (e.g., careless driving) that resulted in no prison time can disqualify an otherwise worthy low-level drug offender from the safety valve, and

Other federal mandatory minimum sentences for other types of crimes – notably, gun possession offenses – are often excessive and apply to low-level offenders who could serve less time in prison, at lower costs to taxpayers, without endangering the public.

The Solution:Create a broader safety valve that applies to all mandatory minimum sentences, and expand the existing drug safety valve to cover more low-level offenders.

When someone is convicted of a specific crime or accepts a plea bargain, they automatically receive at least a pre-established minimum sentence for that crime. It may come as a surprise that it’s actually Congress – not a judge – that sets those minimums. The judge can choose to increase the sentence from the minimum required, but cannot lessen the sentence – except for the Safety Valve Provision if it’s applicable.

In 1984 Congress passed the Safety Valve Provision as part of the Sentencing Reform Act. The purpose of the Safety Valve Provision was to ensure that individuals convicted of non-violent, low-level offenses who didn’t have a criminal history did not receive unreasonably disproportionate sentences. It generally applies to drug crimes with a mandatory minimum.

Each federal crime carries its own offense level, which falls between one and 43; the higher the number, the more serious the crime or aggravating factors. The Safety Valve Provision provides a two-point reduction in the offense level. Alternatively, if a suspect is found to obstruct justice during the investigation, the offense level is then increased by two points. If that same person is shown to be remorseful for their wrongdoing, their offense level may be decreased by two points. While two points may not seem like much, those two points can help to drastically reduce the length of one’s sentence.

The Safety Valve Provision does not apply to everyone; the individual must be eligible for it. To be eligible, the individual must meet the following requirements:

If the offender has a criminal history, the sentencing guidelines will assign specific appoints to those prior convictions. They must not have more than four points for their criminal history (not including any one-point offenses).

Not every crime is eligible for the Safety Valve Provision either. In fact, only those crimes that the statute lists are eligible. These charges include:

If you have been charged with a crime, you may have options. You have the right to defend yourself and prove your innocence. Your best bet of doing so successfully is with the help of a knowledgeable and experienced North Carolina criminal defense attorney who understands what you are up against and will fight on your behalf.

At Hancock Law Firm, PLLC, we fully understand what is at stake and will do everything that we can to help you to fight this order. To learn more or to schedule a free consultation, contact us today!

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Imagine this scenario: Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents bust a small-time drug dealer for, let’s say, nickel-and-diming in heroin. They take him to booking, run his fingerprints and discover this is his third arrest. As a multiple offender facing a long stretch in prison and with a public defender at his side, the suspect offers a deal.

The lead agent and his partner glance at each other. Here it is: a chance to nail the slippery kingpin who runs a multi-million dollar heroin ring that covers three states, but who has somehow managed to elude capture again and again. Never mind that coincidentally their case-closure rate will skyrocket, making them look good. There is a brief pause as the lead agent again glances at his partner, then back at our suspect.

You might think so, and you’d be right. But in the daily trenches of law enforcement, this scenario is not as far-fetched as it appears. In fact, wheeling and dealing is more of a way of life than many police officers and prosecutors care to openly admit. It is, quite simply, the practice of using snitches to obtain convictions. [See: PLN, June 2010, p.1; Feb. 2006, p.28].

But wait, you say. What about the old saying, “snitches get stitches?” Don’t rats end up at the bottom of the nearest river? If that’s true, then the river bottom is a very crowded place.

Nationwide, court records indicate that 25% of offenders sent to federal prison for drug-related crimes provided information to prosecutors in exchange for shorter sentences. In some jurisdictions, like Idaho, Colorado and the Eastern District of Kentucky, more than half did. Sometimes these sentence reductions can amount to 50% or more, according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

Given that incentive, it’s inevitable that some prisoners would find a way to profit from such a dysfunctional system. According to a 2012 USA Today investigation that examined hundreds of thousands of court cases, “snitching has become so commonplace that in the past five years at least 48,895 federal convicts – one out of every eight – had their prison sentences reduced in exchange for helping government investigators....”

Citizens who live their lives happily ignorant of the criminal justice system are unaware that it is a closed loop, starting at the top. Judges, many of whom are former prosecutors and who draw their paychecks from the same government that pays the police and prosecution, are generally hesitant to cast doubt on the legitimacy of their brethren’s crime-fighting methods. Further, judge-made case law over the years has upheld the right of the police to use almost any tactic to solve crimes, including lying and the use of informants.

As a result, prosecutors at both the state and federal levels face few checks upon their power. Knowing that jurors fear crime and seek safer neighborhoods, U.S. Attorneys and their local district attorney counterparts gather information to use as evidence in criminal cases from whomever they can, including prisoners seeking to shorten their sentences.

The incarcerated – and the people who guard them – know there are few secrets in jail or prison. People talk about everything, including their cases. The more canny and opportunistic prisoners realize from first-hand experience that prosecutors “pay” well with sentence reductions for information on someone they have insufficient evidence to convict.

To the naïve or uninitiated, law enforcement, in its battle against crime, should be able to use every tool at its disposal. If that means relying on testimony from one criminal to convict another, so be it. Except in the most obvious cases of prosecutorial overreach, juries hold their collective n

8613371530291

8613371530291