boiler safety valve sizing supplier

A safety valve must always be sized and able to vent any source of steam so that the pressure within the protected apparatus cannot exceed the maximum allowable accumulated pressure (MAAP). This not only means that the valve has to be positioned correctly, but that it is also correctly set. The safety valve must then also be sized correctly, enabling it to pass the required amount of steam at the required pressure under all possible fault conditions.

Once the type of safety valve has been established, along with its set pressure and its position in the system, it is necessary to calculate the required discharge capacity of the valve. Once this is known, the required orifice area and nominal size can be determined using the manufacturer’s specifications.

In order to establish the maximum capacity required, the potential flow through all the relevant branches, upstream of the valve, need to be considered.

In applications where there is more than one possible flow path, the sizing of the safety valve becomes more complicated, as there may be a number of alternative methods of determining its size. Where more than one potential flow path exists, the following alternatives should be considered:

This choice is determined by the risk of two or more devices failing simultaneously. If there is the slightest chance that this may occur, the valve must be sized to allow the combined flows of the failed devices to be discharged. However, where the risk is negligible, cost advantages may dictate that the valve should only be sized on the highest fault flow. The choice of method ultimately lies with the company responsible for insuring the plant.

For example, consider the pressure vessel and automatic pump-trap (APT) system as shown in Figure 9.4.1. The unlikely situation is that both the APT and pressure reducing valve (PRV ‘A’) could fail simultaneously. The discharge capacity of safety valve ‘A’ would either be the fault load of the largest PRV, or alternatively, the combined fault load of both the APT and PRV ‘A’.

This document recommends that where multiple flow paths exist, any relevant safety valve should, at all times, be sized on the possibility that relevant upstream pressure control valves may fail simultaneously.

The supply pressure of this system (Figure 9.4.2) is limited by an upstream safety valve with a set pressure of 11.6 bar g. The fault flow through the PRV can be determined using the steam mass flow equation (Equation 3.21.2):

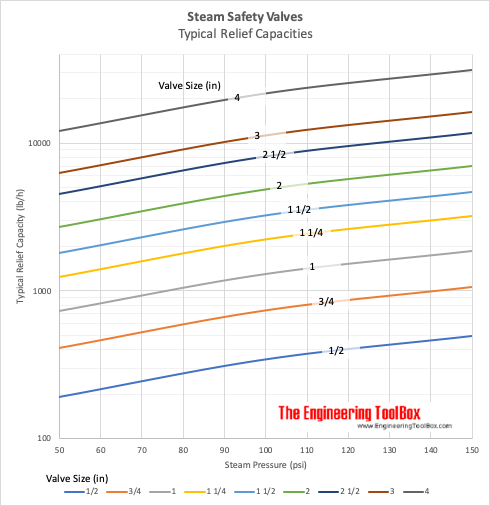

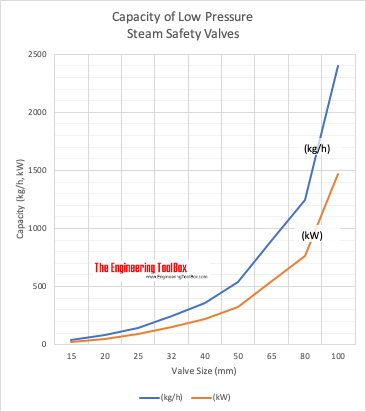

Once the fault load has been determined, it is usually sufficient to size the safety valve using the manufacturer’s capacity charts. A typical example of a capacity chart is shown in Figure 9.4.3. By knowing the required set pressure and discharge capacity, it is possible to select a suitable nominal size. In this example, the set pressure is 4 bar g and the fault flow is 953 kg/h. A DN32/50 safety valve is required with a capacity of 1 284 kg/h.

Where sizing charts are not available or do not cater for particular fluids or conditions, such as backpressure, high viscosity or two-phase flow, it may be necessary to calculate the minimum required orifice area. Methods for doing this are outlined in the appropriate governing standards, such as:

Coefficients of discharge are specific to any particular safety valve range and will be approved by the manufacturer. If the valve is independently approved, it is given a ‘certified coefficient of discharge’.

This figure is often derated by further multiplying it by a safety factor 0.9, to give a derated coefficient of discharge. Derated coefficient of discharge is termed Kdr= Kd x 0.9

Critical and sub-critical flow - the flow of gas or vapour through an orifice, such as the flow area of a safety valve, increases as the downstream pressure is decreased. This holds true until the critical pressure is reached, and critical flow is achieved. At this point, any further decrease in the downstream pressure will not result in any further increase in flow.

A relationship (called the critical pressure ratio) exists between the critical pressure and the actual relieving pressure, and, for gases flowing through safety valves, is shown by Equation 9.4.2.

Overpressure - Before sizing, the design overpressure of the valve must be established. It is not permitted to calculate the capacity of the valve at a lower overpressure than that at which the coefficient of discharge was established. It is however, permitted to use a higher overpressure (see Table 9.2.1, Module 9.2, for typical overpressure values). For DIN type full lift (Vollhub) valves, the design lift must be achieved at 5% overpressure, but for sizing purposes, an overpressure value of 10% may be used.

For liquid applications, the overpressure is 10% according to AD-Merkblatt A2, DIN 3320, TRD 421 and ASME, but for non-certified ASME valves, it is quite common for a figure of 25% to be used.

Backpressure - The sizing calculations in the AD-Merkblatt A2, DIN 3320 and TRD 421 standards account for backpressure in the outflow function,(Ψ), which includes a backpressure correction.

Two-phase flow - When sizing safety valves for boiling liquids (e.g. hot water) consideration must be given to vaporisation (flashing) during discharge. It is assumed that the medium is in liquid state when the safety valve is closed and that, when the safety valve opens, part of the liquid vaporises due to the drop in pressure through the safety valve. The resulting flow is referred to as two-phase flow.

The required flow area has to be calculated for the liquid and vapour components of the discharged fluid. The sum of these two areas is then used to select the appropriate orifice size from the chosen valve range. (see Example 9.4.3)

Many standards do not actually specify sizing formula for two-phase flow and recommend that the manufacturer be contacted directly for advice in these instances.

In order to ensure that the maximum allowable accumulation pressure of any system or apparatus protected by a safety valve is never exceeded, careful consideration of the safety valve’s position in the system has to be made. As there is such a wide range of applications, there is no absolute rule as to where the valve should be positioned and therefore, every application needs to be treated separately.

A common steam application for a safety valve is to protect process equipment supplied from a pressure reducing station. Two possible arrangements are shown in Figure 9.3.3.

The safety valve can be fitted within the pressure reducing station itself, that is, before the downstream stop valve, as in Figure 9.3.3 (a), or further downstream, nearer the apparatus as in Figure 9.3.3 (b). Fitting the safety valve before the downstream stop valve has the following advantages:

• The safety valve can be tested in-line by shutting down the downstream stop valve without the chance of downstream apparatus being over pressurised, should the safety valve fail under test.

• When setting the PRV under no-load conditions, the operation of the safety valve can be observed, as this condition is most likely to cause ‘simmer’. If this should occur, the PRV pressure can be adjusted to below the safety valve reseat pressure.

Indeed, a separate safety valve may have to be fitted on the inlet to each downstream piece of apparatus, when the PRV supplies several such pieces of apparatus.

• If supplying one piece of apparatus, which has a MAWP pressure less than the PRV supply pressure, the apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve, preferably close-coupled to its steam inlet connection.

• If a PRV is supplying more than one apparatus and the MAWP of any item is less than the PRV supply pressure, either the PRV station must be fitted with a safety valve set at the lowest possible MAWP of the connected apparatus, or each item of affected apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve.

• The safety valve must be located so that the pressure cannot accumulate in the apparatus viaanother route, for example, from a separate steam line or a bypass line.

It could be argued that every installation deserves special consideration when it comes to safety, but the following applications and situations are a little unusual and worth considering:

• Fire - Any pressure vessel should be protected from overpressure in the event of fire. Although a safety valve mounted for operational protection may also offer protection under fire conditions,such cases require special consideration, which is beyond the scope of this text.

• Exothermic applications - These must be fitted with a safety valve close-coupled to the apparatus steam inlet or the body direct. No alternative applies.

• Safety valves used as warning devices - Sometimes, safety valves are fitted to systems as warning devices. They are not required to relieve fault loads but to warn of pressures increasing above normal working pressures for operational reasons only. In these instances, safety valves are set at the warning pressure and only need to be of minimum size. If there is any danger of systems fitted with such a safety valve exceeding their maximum allowable working pressure, they must be protected by additional safety valves in the usual way.

In order to illustrate the importance of the positioning of a safety valve, consider an automatic pump trap (see Block 14) used to remove condensate from a heating vessel. The automatic pump trap (APT), incorporates a mechanical type pump, which uses the motive force of steam to pump the condensate through the return system. The position of the safety valve will depend on the MAWP of the APT and its required motive inlet pressure.

This arrangement is suitable if the pump-trap motive pressure is less than 1.6 bar g (safety valve set pressure of 2 bar g less 0.3 bar blowdown and a 0.1 bar shut-off margin). Since the MAWP of both the APT and the vessel are greater than the safety valve set pressure, a single safety valve would provide suitable protection for the system.

Here, two separate PRV stations are used each with its own safety valve. If the APT internals failed and steam at 4 bar g passed through the APT and into the vessel, safety valve ‘A’ would relieve this pressure and protect the vessel. Safety valve ‘B’ would not lift as the pressure in the APT is still acceptable and below its set pressure.

It should be noted that safety valve ‘A’ is positioned on the downstream side of the temperature control valve; this is done for both safety and operational reasons:

Operation - There is less chance of safety valve ‘A’ simmering during operation in this position,as the pressure is typically lower after the control valve than before it.

Also, note that if the MAWP of the pump-trap were greater than the pressure upstream of PRV ‘A’, it would be permissible to omit safety valve ‘B’ from the system, but safety valve ‘A’ must be sized to take into account the total fault flow through PRV ‘B’ as well as through PRV ‘A’.

A pharmaceutical factory has twelve jacketed pans on the same production floor, all rated with the same MAWP. Where would the safety valve be positioned?

One solution would be to install a safety valve on the inlet to each pan (Figure 9.3.6). In this instance, each safety valve would have to be sized to pass the entire load, in case the PRV failed open whilst the other eleven pans were shut down.

If additional apparatus with a lower MAWP than the pans (for example, a shell and tube heat exchanger) were to be included in the system, it would be necessary to fit an additional safety valve. This safety valve would be set to an appropriate lower set pressure and sized to pass the fault flow through the temperature control valve (see Figure 9.3.8).

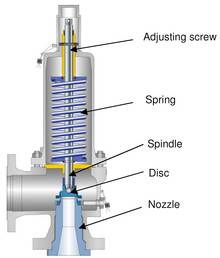

Safety valves are an arrangement or mechanism to release a substance from the concerned system in the event of pressure or temperature exceeding a particular preset limit. The systems in the context may be boilers, steam boilers, pressure vessels or other related systems. As per the mechanical arrangement, this one get fitted into the bigger picture (part of the bigger arrangement) called as PSV or PRV that is pressure safety or pressure relief valves.

This type of safety mechanism was largely implemented to counter the problem of accidental explosion of steam boilers. Initiated in the working of a steam digester, there were many methodologies that were then accommodated during the phase of the industrial revolution. And since then this safety mechanism has come a long way and now accommodates various other aspects.

These aspects like applications, performance criteria, ranges, nation based standards (countries like United States, European Union, Japan, South Korea provide different standards) etc. manage to differentiate or categorize this safety valve segment. So, there can be many different ways in which these safety valves get differentiated but a common range of bifurcation is as follows:

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) I tap is a type of safety valve which opens with respect to 3% and 4% of pressure (ASME code for pressure vessel applications) while ASME VIII valve opens at 10% over pressure and closes at 7%. Lift safety valves get further classified as low-lift and full lift. The flow control valves regulate the pressure or flow of a fluid whereas a balanced valve is used to minimize the effects induced by pressure on operating characteristics of the valve in context.

A power operated valve is a type of pressure relief valve is which an external power source is also used to relieve the pressure. A proportional-relief valve gets opened in a relatively stable manner as compared to increasing pressure. There are 2 types of direct-loaded safety valves, first being diaphragms and second: bellows. diaphragms are valves which spring for the protection of effects of the liquid membrane while bellows provide an arrangement where the parts of rotating elements and sources get protected from the effects of the liquid via bellows.

In a master valve, the operation and even the initiation is controlled by the fluid which gets discharged via a pilot valve. Now coming to the bigger picture, the pressure safety valves based segment gets classified as follows:

So all in all, pressure safety valves, pressure relief valves, relief valves, pilot-operated relief valves, low pressure safety valves, vacuum pressure safety valves etc. complete the range of safety measures in boilers and related devices.

Safety valves have different discharge capacities. These capacities are based on the geometrical area of the body seat upstream and downstream of the valve. Flow diameter is the minimum geometrical diameter upstream and downstream of the body seat.

The nominal size designation refers to the inlet orifice diameter. A safety Valve"s theoretical flowing capacity is the mass flow through an orifice with the same cross-sectional area as the valve"s flow area. This capacity does not account for the flow losses caused by the valve. The actual capacity is measured, and the certified flow capacity is the actual flow capacity reduced by 10%.

A safety valve"s discharge capacity is dependent on the set pressure and position in a system. Once the set pressure is calculated, the discharge capacity must be determined. Safety valves may be oversized or undersized depending on the flow throughput and/or the valve"s set pressure.

The actual discharge capacity of a safety valve depends on the type of discharge system used. In liquid service, safety valves are generally automatic and direct-pressure actuated.

A safety valve is used to protect against overpressure in a fluid system. Its design allows for a lift in the disc, indicating that the valve is about to open. When the inlet pressure rises above the set pressure, the guide moves to the open position, and media flows to the outlet via the pilot tube. Once the inlet pressure falls below the set pressure, the main valve closes and prevents overpressure. There are five criteria for selecting a safety valve.

The first and most basic requirement of a safety valve is its ability to safely control the flow of gas. Hence, the valve must be able to control the flow of gas and water. The valve should be able to withstand the high pressures of the system. This is because the gas or steam coming from the boiler will be condensed and fill the pipe. The steam will then wet the safety valve seat.

The other major requirement for safety valves is their ability to prevent pressure buildup. They prevent overpressure conditions by allowing liquid or gas to escape. Safety valves are used in many different applications. Gas and steam lines, for example, can prevent catastrophic damage to the plant. They are also known as safety relief valves. During an emergency, a safety valve will open automatically and discharge gas or liquid pressure from a pressurized system, preventing it from reaching dangerous levels.

The discharge capacity of a safety valve is based on its orifice area, set pressure, and position in the system. A safety valve"s discharge capacity should be calculated based on the maximum flow through its inlet and outlet orifice areas. Its nominal size is often determined by manufacturer specifications.

Its discharge capacity is the maximum flow through the valve that it can relieve, based on the maximum flow through each individual flow path or combined flow path. The discharge pressure of the safety valve should be more than the operating pressure of the system. As a thumb rule, the relief pressure should be 10% above the working pressure of the system.

It is important to choose the discharge capacity of a safety valve based on the inlet and output piping sizes. Ideally, the discharge capacity should be equal to or greater than the maximum output of the system. A safety valve should also be installed vertically and into a clean fitting. While installing a valve, it is important to use a proper wrench for installation. The discharge piping should slope downward to drain any condensate.

The discharge capacity of a safety valve is measured in a few different ways. The first is the test pressure. This gauge pressure is the pressure at which the valve opens, while the second is the pressure at which it re-closes. Both are measured in a test stand under controlled conditions. A safety valve with a test pressure of 10,000 psi is rated at 10,000 psi (as per ASME PTC25.3).

The discharge capacity of a safety valve should be large enough to dissipate a large volume of pressure. A small valve may be adequate for a smaller system, but a larger one could cause an explosion. In a large-scale manufacturing plant, safety valves are critical for the safety of personnel and equipment. Choosing the right valve size for a particular system is essential to its efficiency.

Before you use a safety valve, you need to know its discharge capacity. Here are some steps you need to follow to calculate the discharge capacity of a safety valve.

To check the discharge capacity of a safety valve, the safety valve should be installed in the appropriate location. Its inlet and outlet pipework should be thoroughly cleaned before installation. It is important to avoid excessive use of PTFE tape and to ensure that the installation is solid. The safety valve should not be exposed to vibration or undue stress. When mounting a safety valve, it should be installed vertically and with the test lever at the top. The inlet connection of the safety valve should be attached to the vessel or pipeline with the shortest length of pipe. It must not be interrupted by any isolation valve. The pressure loss at the inlet of a safety valve should not exceed 3% of the set pressure.

The sizing of a safety valve depends on the amount of fluid it is required to control. The rated discharge capacity is a function of the safety valve"s orifice area, set pressure, and position in the system. Using the manufacturer"s specifications for orifice area and nominal size of the valve, the capacity of a safety valve can be determined. The discharge flow can be calculated using the maximum flow through the valve or the combined flows of several paths. When sizing a safety valve, it"s necessary to consider both its theoretical and actual discharge capacity. Ideally, the discharge capacity will be equal to the minimum area.

To determine the correct set pressure for a safety valve, consider the following criteria. It must be less than the MAAP of the system. Set pressure of 5% greater than the MAAP will result in an overpressure of 10%. If the set pressure is higher than the MAAP, the safety valve will not close. The MAAP must never exceed the set pressure. A set pressure that is too high will result in a poor shutoff after discharge. Depending on the type of valve, a backpressure variation of 10% to 15% of the set pressure cannot be handled by a conventional valve.

Boiler explosions have been responsible for widespread damage to companies throughout the years, and that’s why today’s boilers are equipped with safety valves and/or relief valves. Boiler safety valves are designed to prevent excess pressure, which is usually responsible for those devastating explosions. That said, to ensure that boiler safety valves are working properly and providing adequate protection, they must meet regulatory specifications and require ongoing maintenance and periodic testing. Without these precautions, malfunctioning safety valves may fail, resulting in potentially disastrous consequences.

Boiler safety valves are activated by upstream pressure. If the pressure exceeds a defined threshold, the valve activates and automatically releases pressure. Typically used for gas or vapor service, boiler safety valves pop fully open once a pressure threshold is reached and remain open until the boiler pressure reaches a pre-defined, safe lower pressure.

Boiler relief valves serve the same purpose – automatically lowering boiler pressure – but they function a bit differently than safety valves. A relief valve doesn’t open fully when pressure exceeds a defined threshold; instead, it opens gradually when the pressure threshold is exceeded and closes gradually until the lower, safe threshold is reached. Boiler relief valves are typically used for liquid service.

There are also devices known as “safety relief valves” which have the characteristics of both types discussed above. Safety relief valves can be used for either liquid or gas or vapor service.

Nameplates must be fastened securely and permanently to the safety valve and remain readable throughout the lifespan of the valve, so durability is key.

The National Board of Boiler and Pressure Vessel Inspectors offers guidance and recommendations on boiler and pressure vessel safety rules and regulations. However, most individual states set forth their own rules and regulations, and while they may be similar across states, it’s important to ensure that your boiler safety valves meet all state and local regulatory requirements.

The National Board published NB-131, Recommended Boiler and Pressure Vessel Safety Legislation, and NB-132, Recommended Administrative Boiler and Pressure Vessel Safety Rules and Regulationsin order to provide guidance and encourage the development of crucial safety laws in jurisdictions that currently have no laws in place for the “proper construction, installation, inspection, operation, maintenance, alterations, and repairs” necessary to protect workers and the public from dangerous boiler and pressure vessel explosions that may occur without these safeguards in place.

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) governs the code that establishes guidelines and requirements for safety valves. Note that it’s up to plant personnel to familiarize themselves with the requirements and understand which parts of the code apply to specific parts of the plant’s steam systems.

High steam capacity requirements, physical or economic constraints may make the use of a single safety valve impossible. In these cases, using multiple safety valves on the same system is considered an acceptable practice, provided that proper sizing and installation requirements are met – including an appropriately sized vent pipe that accounts for the total steam venting capacity of all valves when open at the same time.

The lowest rating (MAWP or maximum allowable working pressure) should always be used among all safety devices within a system, including boilers, pressure vessels, and equipment piping systems, to determine the safety valve set pressure.

Avoid isolating safety valves from the system, such as by installing intervening shut-off valves located between the steam component or system and the inlet.

Contact the valve supplier immediately for any safety valve with a broken wire seal, as this indicates that the valve is unsafe for use. Safety valves are sealed and certified in order to prevent tampering that can prevent proper function.

Avoid attaching vent discharge piping directly to a safety valve, which may place unnecessary weight and additional stress on the valve, altering the set pressure.

Pressure relief valves are used to protect equipment from excessive overpressure. Properly sized relief valves will provide the required protection, while also avoiding issues with excessive flow rates, including: possible valve damage, impaired performance, undersized discharge piping and effluent handling systems, and higher costs.

Many scenarios can result in an increased vessel pressure, and each scenario may result in a different valve size. It is generally recommended to perform multiple case studies to find the most conservative sizing. Some typical cases include:

In any of these scenarios, the pressure will increase until a predetermined relief pressure is reached, at which point the relief pressure valve will open, decreasing the pressure after the turnaround time. The first step in sizing a Relief Valve in ProMax is to determine which scenario you are interested in modeling.

The Relief Valve Sizing in ProMax is performed as a stream analysis. Any stream in ProMax may have one or more Relief Valve Sizing Analyses added, so multiple cases can be studied in a single stream if desired.

There are many different standards for Relief Valve Sizing, each applying different assumptions, thus giving different results. For instance, API 520, one of the most cited standards, assumes both a mechanical and thermodynamic equilibrium, and constant phase properties during relief. Alternatively, the EN ISA 4126 standard accounts for thermodynamic non-equilibrium. ProMax currently supports six different sets of Relief Valve Sizing Standards:

Next, an appropriate relief type must be selected, as sizing depends on the type of relief device selected. The operation of conventional spring-loaded pressure relief valve is based on a force balance: the spring-load is preset to apply a force opposite in amount to the pressure force exerted by the fluid on the other side when it is at the set pressure. When the fluid pressure exceeds the set pressure, the pressure force overcomes the spring force, and the valve opens. Any back pressure (downstream pressure) is additive to the spring force; if this back pressure varies, then the pressure at which the valve opens will vary. Bellows are used to maintain a constant relief pressure despite back pressure variations. Rupture disc relief valves do not reclose after activation; preference should usually be given to reclosing relief devices for both safety and reliability. The most common valve types include:

Balanced Bellows- spring loaded pressure relief valve that incorporates a bellows for minimizing the effect of back pressure on the operational characteristics of the valve.

Pilot Operated- a pressure relief valve in which the major relieving device or main valve is combined with and controlled by a self-actuated auxiliary pressure relief valve (pilot).

The Relief Temperature is determined by which pressure relief scenario you have chosen to model, and should be the temperature of the fluid at the time that the valve is expected to open. ProMax assumes that the Relief Temperature will be the current stream temperature, however, if your particular scenario requires that this be adjusted, it can be overwritten directly in the analysis dialog.

The Over Pressure is usually expressed as a percentage of the Set Pressure. For spring-operated relief valves, a small amount of leakage occurs at 92-95% of theSet Pressure, and sufficient Over Pressure is necessary to achieve full lift. ASME-certified relief valves are required to reach full-rated capacity at 10% or less overpressure.

Once you’ve determined your emergency scenario, and specified the relieving conditions and flowrate, and the appropriate standard, ProMax will calculate the Effective Discharge Area. This value is used to select the appropriately sized Pressure Relief Valve.

Although an orifice is often used to describe the minimum flow area constricted in the valve, the geometry and relief area calculations are more appropriately modeled based on an ideal (isentropic) nozzle. The expression for the mass flux (Gn) in an ideal nozzle is obtained directly from Bernoulli’s equation in the nozzle:

distribution of fluid phases, interaction, and transformation of the phases, sizing a two-phase relief scenario is considerably more complex than single-phase. The Mass Flux calculation varies depending on the relieving fluid type:

This type of flow is often encountered at metering devices in chemical processing and in relief valve sizing applications where both non-condensable and condensable (flashing) components

This term is an estimation used in sizing pressure relief valves for two-phase liquid/vapor applications when the system has less than 0.1 wt% H2, a nominal boiling range less than 150°F, and

As such, there are multiple methods of approximating the latent heat, and the Relief Valve Sizing analysis follows the methodology of the standards. For example, the API 520 standard defines “latent heat” as

Darby, R., Meiller, P. R., Stockton, J. R. (2001). Select the Best Model for Two-Phase Relief Sizing, Chemical Engineering Progress, Vol.97, No.5, pp 56.

**Update to this article, June 7, 2022 : If you found this article helpful, here is a link to another article I recently found that does a nice job explaining the topic: ENGINEERS BEWARE: API vs ASME Relief Valve Orifice Size – Petro Chem Engineering (petrochemengg.com)

NOTE: this article is written to an audience that is familiar with PSVs, PSV sizing, and API and ASME standards at a basic level. I initially wrote this article in early 2017, and due to some great input and questions made significant revisions to increase clarity in mid-2018. I hope it is helpful to you, please send me a message with any comments/questions!

If you"ve ever sized/selected a Pressure Safety-Relief Valve (PSV) using vendor sizing programs or good-old hand calculations, you"ve probably run into a very strange anomaly: Why does a PSV orifice size change between American Petroleum Institute (API) and American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) data sets? What is an "effective" orifice area? How do I know which standard to use when selecting a PSV?

Usually, this issue is one of curiosity and doesn"t affect the end result of what valve is chosen. Common practice is to default to API sizing equations and parameters, and only use ASME data sets for situations outside of the API letter-designations. But what if I told you that approach is likely causing you to oversize about 10% of your PSVs and their respective piping systems?

Too often, we leave that third part out of the process, and simply calculate relief loads and select valves using API techniques, without ever checking our selection against certified ASME data. Proper application of these standards is the first key point of this article:

Initial sizing and valve selection is done using API equations, and final valve selection and certification is done using ASME-certified coefficients and capacities.

When sizing a PSV, the sizing equations are always API 520. When a PSV is certified, it is always certified to ASME BPVC (whether one “selects” ASME certification or not!) It"s important to remember that the ASME BPVC is the "code", the standard to which we must design. API 520/526 are "recommended practices" which were developed to give engineers a tool to meet the ASME requirements. Another way to look at it: ASME BPVC sets the goal, API 520/526 provide the instructions, and ASME has the final say.

The BPVC is an enormous code, and not reviewed in detail here. On the subject of PSVs, it basically says that a PSV must be capable of relieving the required load, and it must be tested in a specific manner to be certified to do so. If a valve is tested per the specific directions in the BPVC, it will be ASME certified and receive an ASME UV stamp.

The first thing API does is attempt to standardize physical PSV sizes and design, and it does so in API RP 526, which is targeted at PSV manufacturers. API provides pre-defined valve sizes, with letter designations D through T (API 526). It also defines other details directed toward valve manufacturers (such as temperature ratings). All of this is intended as minimum design standards, and manufacturers are free to exceed these parameters as they wish.

The second thing API does is provide standardized equations and parameters to use when trying to figure out just what size of a PSV one needs for a particular scenario. The equations account for design parameters that ASME doesn"t speak to, such as specific fluid properties, backpressures, critical flow, two-phase flow, and many other aspects of fluid dynamics that will affect the ability of a particular valve to relieve a required load.

API sizing equations are by nature theoretical, standardized, and use default or "dummy" values for several sizing parameters that may or may not reflect the actual values for any specific valve.

API RP 520 very clearly talks about this, and emphasizes that the intended use of its equations is to determine a preliminary valve size, which should be verified with actual data. API intends PSV sizing to be a two-step process, but we are often unaware of this because we (gasp) don’t read the full standard, and/or rely solely on vendor sizing software that hides the iteration from us. See API 520, part 1, section 5.2 for further explanation.

When valves are built, they are built to the API RP 526 standard, however, as one might imagine, when valves are actually tested and certified, the results don’t match up identically to the theoretical values that were calculated. This is where API and ASME intersect; we switch from calculations (API) which were used as a basis to design the valve, to actual empirical data (ASME) to certify the valve. When a valve manufacturer gets the UV code stamp that certifies the valve orifice size and capacity, it is based on actual test results, not API sizing standards. And ASME (which came first) does not have tiered letter designations. The typical D, E, F, etc. sizes we refer to are strictly an API tool, and ASME’s capacity certifications are completely independent of them!

3. A third-party Engineer (you), trying to select a PSV, runs a sizing calculation using API 520 equations on ABC Valve Company"s sizing software, gets a result that requires 4.66in2 to relieve the load, and is now thoroughly confused on what size valve to select.

If one selects the API data set on the sizing software in this example, it will automatically eliminate N-orifice valves as an option, and bump the user up to a P-orifice. However, if one simply selects the ASME data set, the N-orifice valve magically reappears as an option. How can this be? Will the N-orifice work or not?

Digest that for a moment. If you’ve sized and purchased more than a dozen PSVs, chances are you have inadvertently selected a PSV a full size larger than you needed to, in a situation much like our example, simply because you chose a PSV based on its API “rating” rather than its real, certified, stamped ASME rating. If that was a small valve, impact was probably nil. But what if this happened on a valve that resulted in selecting a 8x10 PSV when you could have used a 6x8?

If you’re like me, that answer isn’t very satisfying. Why on earth is this so confusing? How can you simply hit a button on the sizing program and a different size of valve is suddenly acceptable? The key lies how the main coefficient of discharge, Kd, is handled, and how capacities are determined.

There are several K values used in API calculations, all of which have generic values defined in API 520 that can be used for preliminary sizing. These are the numbers used in initial sizing calculations to get us close, then (if we do this correctly) replaced with the actual/tested/empirical/ASME values when we get a certified valve. Remember, anytime you hear “certified” or “stamped”, think ASME.

Let’s take the numbers from the example above, which came from an attempt to size a valve for liquid relief. API says to use a value of Kd=0.65 for liquid relief. If one uses the API data set on the vendor software, then the calculation stops here, and you get a required area of 4.66in2. When you select a valve, you’re comparing that to the API effective (actual) area of an N orifice, which is 4.34 in2, which is obviously too small and you’d logically step up to a P orifice. However….

Remember that the API N-orifice area is just the benchmark, a minimum requirement, and may or may not (most likely not) reflect the actual area of a real-life PSV. Once a valve is selected, all of those K values and capacities should be replaced with actual ASME-certified K values, also determined by testing, that are specific to each valve model, and the calculations performed again.

Normally, ASME-certified K-values are smaller than the API dummy values, driving up the required orifice area. So valve manufacturers have to over-design their valves to make up for it, resulting in ASME-certified areas and capacities that typically exceed the benchmark API ones. The end result of all this?

It (almost) all boils down to one sneaky little sentence in the ASME BPVC which mandates a 10% safety factor on the empirically-determined Kd that “de-rates” the valve (see ASME BPVC Section VIII, UG-131.e.2). This tidbit seems to be a little-known fact that is key to proper PSV sizing and selection, because as engineers we often pile safety factors upon each other and oversize our equipment. I cannot highlight this enough:

I mentioned above that ASME K values are nearly always lower than API values, due to this 10% de-rating. The PSV in our example scenario has a determined Kd of 0.73, which is adjusted down by 10% for a final AMSE Kd of 0.66, slightly higher than the dummy API value (that just means that this particular valve proved it could do about 11% better than the minimum theoretical flow calculated by API when it was tested). So, for our valve in question, the Required ASME area is slightly less than the API area. This is atypical, but not unheard of, and again points to the importance of checking the ASME ratings of any valve you select, and comparing against the API benchmarks.

When you choose to use the ASME data on a specific valve, it’s not just the Kd sizing factor that changes; the actual orifice area and therefore the capacity of the valve also adjusts to empirical, certified values. You can generally expect both values to increase over the API values.

Why is this? Simply that any given real-world valve is usually over-designed so that it will meet and exceed the required minimum capacity of its corresponding API size. What a simple concept, but so often overlooked by engineers!

*Note: this is data from a real case; the specific PSV make/model is omitted. Did you catch the result? The actual, certified capacity of this valve is nearly 13% higher than the generic N-orifice valve, and that includes its 10% safety factor!

With this adjusted orifice area, we can compare to the ASME certified area (which is always going to be larger than the API area), and we have our final answer for the valve size. Often this will not result in a different choice of valve, but sometimes, as in the example case, it will allow us to use a valve with an API letter designation that did not appear large enough based on its API effective area. This can save time and money for our plants by preventing over-sizing valves, leading to smaller piping systems to support them. And remember, the ASME values are empirical and have a 10% safety factor built in, so we don’t need to worry about cutting the design too close; the conservatism is already built in to the method. We can choose the Brand X N-orifice valve and sleep well at night!

Avoid simply defaulting to the API data set for the final “rating” or data sheet when selecting a PSV. Use API sizing calculations as they are intended: for preliminary valve selection. Then switch to the ASME data set. This will often (but not always, remember, it"s valve-specific) result in two differences:

Closing notes: PSV sizing and selection is a big topic, and this article only addresses one issue. I have chosen to omit specific code references and quotations in an attempt to make this a general guideline that is useful for most engineers, not an interpretation of the codes. Many tangent issues can spin off from this article; I will be happy to help with any questions it may generate. Please email me any comments or suggestions, I welcome all input.

8613371530291

8613371530291