fema safety valve quotation

Controls Supply Chain also supplies products and components of Fema (Honeywell). This brand has an extensive experience in the development and manufacture of safety valves. Over the years this brand has become an example for other parties. Fema designs and builds specialized safety valves for various industries like chemical, petrochemical, metallurgy, cryogenic and food.

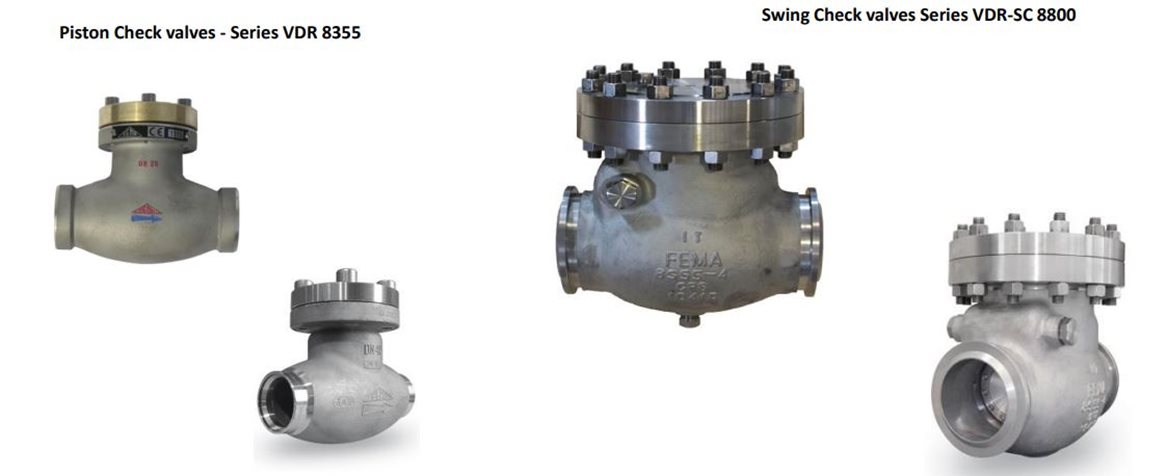

The product range of Fema includes safety valves, switches, control valves, ball valves, pressure switches, differential pressure switches, pressure transmitters and ball valves and all have the necessary certificates according to PED – Pressure Equipment Directive, the Gas Appliance Directive and the Explosion Directive. Fema provides solutions for your safety.

The products of Fema can be used in many applications such as monitoring of flammable liquids and gases, as well as steam and hot water. Sensors and pressure switches play an important role in the management of plant and machinery. With products of Fema pressure it is possible to safely monitor and control. Clients appreciate the competence of this brand and the reliability.

Besides products for steam generators, heating, biogas units, pumping stations, water stations, ventilation and air conditioning, transportation, manufacturing facilities, machine construction, welding and painting systems and hazardous applications FEMA delivers also products for water purification, cleaning systems, chip factories, greenhouses, turbine test benches and printing machines.

FEMA designs and manufactures safety and cryogenic valves for the oil & gas, cryogenic and aerospace industries, including special safety products and cold protection systems.

FEMA manufactures safety actuated valves including cryogenic pneumatic ON-OFF valves, pneumatic cryogenic control valves, pneumatic cryogenic control valves for cold box applications, pneumatic cryogenic control valves, angle cryogenic safety valves.

FEMA Corporation’s high-frequency pilot operated hydraulic solenoid valves are frictionless hydraulic pressure modulation valves that operate with direct-current or a simple >1000 Hz high-frequency electrical input. Our two-stage cartridge valves feature E-H pilot proportional pressure control to modulate pressure from 0 to 30 bar, and flow range near 4 liters per second at 20 bar delta. The two stages provide high-spool driving force, and our advanced manufacturing process for the piloted design maintains efficiency in heavily contaminated systems. FEMA’s high-frequency valves, often used in transmission clutch and PTO control, offer high reliability, low cost and proportionality while maintaining a small size and weight.

In 2011, significant flooding caused erosion and degradation of the sanitary sewer system operated by the City of Pierre (Applicant), resulting in a sinkhole stretching along a sewer line from a manhole. The Applicant received two bids from contractors to perform permanent repairs to the sinkhole and remove and replace the sewer line. The city awarded the contract to the lower bidder. During excavation and repair, additional damage was discovered on two additional sewer lines and the manhole. On November 29, 2011, a change order was issued for the additional repair work, totaling $237,244.86. FEMA approved Project Worksheet (PW) 2432 for $90,775.33, covering the costs of temporary repair work, direct administrative costs, the initial contract for the permanent repair of the sewer line (which was $86,000.00), and a contract estimate for curb and gutter work. PW 2432 did not include the costs of work performed under the $237,244.86 change order to the contract because, FEMA determined, there was a “lack of specific documentation regarding costs and quantities” and “proof that the damages were flood-related.” The Applicant appealed this decision, and the Acting Regional Administrator approved the appeal in part determining that neither the initial contract procurement nor the change order comported with applicable procurement regulations. On second appeal, the Applicant argues that its actions were justified under applicable procurement laws, and that the entire scope of work is eligible for PA funding.

This is in response to a letter from your office dated October 25, 2013, which transmitted the referenced second appeal on behalf of the City of Pierre (Applicant). The Applicant is appealing the Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) denial of its request for certain costs associated with sewer line repairs caused by heavy flooding.

As explained in the enclosed analysis, FEMA is partially approving the Applicant’s second appeal. The damage to the sewer lines and manhole was caused by the disaster event, and the work as described in the change order was necessary to accomplish the needed repairs. The Applicant complied with the method of procurement requirements under 44 C.F.R. § 13.36(d) for both the original procurement and the change order, but failed to comply with the cost analysis requirement for the change order required by 44 C.F.R. § 13.36(f). Notwithstanding this noncompliance, FEMA will not take enforcement action by reducing the otherwise eligible costs incurred by the Applicant for eligible work. FEMA will, therefore, increase the amount awarded under PW 2432 by an additional $213,570.86 for costs incurred under the change order, $3,397.10 for the manhole, $2,359.85 for curb and gutter repair and replacement, and $5,666.05 for direct administrative costs related to this project.

In the spring and summer of 2011, warm temperatures caused significant runoff and flooding in the state of South Dakota following a winter with above-normal snowfall. On May 13, 2011, the President declared a major disaster for the state (FEMA-1984-DR-SD), with an incident period of March 11 to July 22, 2011.

The Applicant received two bids from contractors to perform permanent repairs to the sinkhole and remove and replace the sewer line, one bid for $86,000.00 and another for $160,400.00. On October 25, 2011, the Applicant awarded a contract to the lower bidder, Morris, Inc. (the “Contractor”). The contract included work immediately adjacent to the manhole and included removal of a minimum of the top half of the impacted manhole. Under the contract, the Contractor was responsible for providing all materials, except for surface gravel, and the Applicant was responsible for replacing asphalt surface material, closing the water line valve, and bypass pumping.

On April 13, 2012, FEMA obligated $90,775.33 in Project Worksheet (PW) 2432, covering the contract and force account work and materials associated with the temporary repair of the sinkhole ($3,484.60), direct administrative costs (DAC) ($94.73), and the initial contract for the permanent repair of the sewer line ($86,000.00), plus a contract estimate for curb and gutter work ($1,196.00).[1] PW 2432 did not include the costs of work performed under the $237,244.86 change order to the contract because, FEMA determined, there was a “lack of specific documentation regarding costs and quantities” and “proof that the damages were flood-related.” According to FEMA, without documentation supporting the $237,244.86 lump-sum change order, it was not possible to determine the reasonableness of those costs. FEMA’s PW notation also stated that the additional damage was discovered after the initial site inspection and had not been inspected by FEMA.

The Applicant submitted a first appeal to the South Dakota Department of Public Safety (Grantee) in a letter dated May 18, 2012, seeking reimbursement of the $237,244.86 change order amount. The Grantee forwarded the letter to FEMA Region VIII in a letter dated July 3, 2012, after requesting and obtaining additional information from the Applicant. The Applicant asserted that the Missouri Avenue manhole displayed obvious displacement following the disaster, with the displacement resulting in the shearing of the three sewer lines entering the manhole. Displaced manholes and sinkholes arose throughout the city, the Applicant explained, with other PWs written to document the costs of their repair. The Applicant stated that the failure became visible around the manhole before excavation began but that the specific lines affected by the manhole’s displacement were not known until a visual inspection after excavation. The damage to the additional lines and manhole became apparent only after the Contractor exposed the structure, the Applicant asserted. Thus, rather than being a “singular repair,” the applicant explained, the repair “became a three[-]phase project involving three excavations and repairs.” According to the Applicant, the Contractor justified the increased costs of $237,244.86, and the Applicant approved the change order in that amount in accordance with applicable procurement procedures. The Applicant noted that the deep repair, water and materials infiltration, nearby utilities, need for sheet piling, and other factors made the project complex and costly.

The Acting RA sought to establish reasonable costs based on FEMA’s Cost Estimating Format (CEF). Applying the CEF the Acting RA, estimated total eligible costs for the work completed amounted to $114,449.33--$23,674.00 above the obligated amount.

The Applicant submitted a second appeal in a letter dated August 28, 2013. The Applicant argues that, given the circumstances it faced, its procurement of both the original contract and the change order complied with applicable procurement laws and procedures. As to the original contract, the Applicant noted that, at the time of the repair, the Missouri River flooding resulted in significantly elevated underground water levels, leaving its sanitary sewer line near the river under 20 feet of water, negatively affecting manholes and the lift station. According to the Applicant, federal and state procurement laws allow for emergency procurement when a threat exists to public health, welfare, or safety, or when a public emergency requires it. The Applicant asserts that sewer line breaks and resulting sewage backup and bypass procedures constituted such a threat and emergency. Moreover, the Applicant states, under federal procurement regulations, small purchases may be accomplished by obtaining several price quotes from different sources; three contractors attended the bid opening and reviewed the original contract scope of work, the Applicant explained, and two submitted bids. The Applicant noted that it accepted the lower bid of $86,000.00, under the small purchase threshold.

Regarding the change order procurement, the Applicant cites a variety of factors it asserts justified its decision under state law, federal law, and FEMA policy to proceed with additional repairs to the newly discovered damage without competing the work. The Applicant points out that the breaks in the three lines affected the main sewer line, which serves more than half of the city’s population. The Applicant notes that above-normal precipitation continued during the repairs and that, given the extended length of the project, repair work—which involved exposed utilities and structures—would take place during below-freezing temperatures as winter set in. The freezing temperatures would affect not only the repairs but also bypass operations, the Applicant argues. In addition, the Applicant notes, the Contractor had already installed sheetpiling, which was actively protecting the site, and was the sole source of sheetpiling in the area. The Applicant also notes the numerous other sewer repairs were required following the disaster event and asserts that utility repairs and levee removals in progress in dozens of counties across South Dakota and in the surrounding state affected contractor availability. Thus, the Applicant argues, the Contractor, already in place, was the only practicable source to continue the repair work.

The Applicant asserts that total project costs (including costs captured on PW 2425) amount to $370,612.96. After taking into account funding provided thus far—the original $90,775.33 obligated in PW 2432; the $23,674.00 in additional costs awarded by the RA; and $7,095.00 for asphalt repairs associated with the site captured in PW 2425—the Applicant requests an additional $249,163.36 for the repairs.[2] The Applicant also seeks an additional $5,666.05 in DAC:Total Project Cost (Requested by Applicant)FEMA Eligible after 1st AppealDifference

The Grantee transmitted the second appeal to the FEMA Region VIII Acting RA in a letter dated October 25, 2013. Applicant representatives provided a presentation to FEMA reiterating and supplementing points raised on second appeal on January 27, 2014.

Section 406 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (“Stafford Act”) authorizes FEMA to provide grant assistance to states, local governments, and certain non-profit organizations for the repair and replacement of facilities damaged or destroyed by a major disaster.[3] FEMA administratively categorizes this work as “permanent work,” Public Assistance Categories C through G. To be eligible for Public Assistance, an item of work must be required as a direct result of the designated event under a major disaster declaration.[4] Work to repair damage that results from a cause other than the designated event outside the incident period (such as a pre- or post-disaster rain, wind, flooding, storms, or normal weather conditions) is not eligible, and it is an applicant’s responsibility to show that the damage is disaster-related.

On first appeal the RA concluded that eligible work included (1) excavation and replacement of 51.9 feet of 10-inch East Line lateral from the manhole toward Pierre Street, along with pea gravel bedding; (2) excavation and replacement of 12 feet of 10-inch West Line lateral from the manhole toward Fort Street, along with pea gravel bedding; (3) excavation and replacement of 20 feet of 12-inch North Line lateral from the manhole toward the lift station, along with pea gravel bedding; and (4) stabilization of the manhole location with gravel and placement of a new concrete base. The RA rejected the Applicant’s assertions that the manhole was damaged by the disaster because the Applicant did not provide supporting document. After a review of the Applicant’s appeal submissions, FEMA concludes that the Applicant has provided documentation—in the form of maps, photographs, reports, charts, e-mail communications, and other materials—sufficiently demonstrating that the damage to the three sewer lines and manhole was caused by the disaster event and that all of the repair work as described in the change order was necessary.

The regulation also sets forth the three competitive methods of procurement to be followed by a local government, which include procurement by small purchase procedures, sealed bidding, and competitive proposals.[8] First, small purchase procedures are those relatively simple and informal procurement methods for securing services, supplies, or other property that do not cost more than the simplified acquisition threshold, which was $150,000 at the time of major disaster FEMA-1984-DR.[9] If small purchase procedures are used, a local government must obtain price or rate quotations from an adequate number of qualified sources.[10] Second, under sealed bidding, a local government publicly solicits bids and a firm-fixed price contract is awarded to the responsible bidder whose bid, conforming with all the material terms and conditions of the invitation for bids, is the lowest in price.[11] The sealed bid method is the preferred method for procuring construction if certain conditions apply.[12] Third, the technique of competitive proposals is normally conducted with more than one source submitting an offer, and either a fixed-price or cost-reimbursement contract is awarded.[13] This method is generally used when conditions are not appropriate for the use of sealed bids.[14]

Once a contract is awarded, a local government may need to make changes to that contract to react to newly encountered circumstances, fix inaccurate or defective specifications, or modify the work to ensure the contract meets the local government’s requirements. A contract “change” is any addition, subtraction, or modification of work under a contract during contract performance.[19] Notwithstanding the need to make appropriate contract changes, a local government may not make a “cardinal change” to a contract so as to circumvent the requirements of 44 C.F.R. § 13.36 for full and open competition. A cardinal change is a significant change in contract work (property or services) that causes a major deviation from the original purpose of the work or the intended method of achievement, or causes a revision of contract work so extensive, significant, or cumulative that, in effect, the contractor is required to perform very different work from that described in the original contract.[20] A modification that comprises a cardinal change constitutes a sole source award, and FEMA evaluates such a modification to determine if the conditions precedent for a noncompetitive procurement at 44 C.F.R. § 13.36(d)(4) have been met.

The regulation at 44 C.F.R. § 13.36(d)(1) provides that small purchase procedures are those relatively simple and informal procurement methods for securing services, supplies, or other property that do not cost more than the simplified acquisition threshold, which was $150,000 at the time of major disaster FEMA-1984-DR.[23] A local government may not break out a larger procurement merely to gain advantage of small purchase procedures. Similarly, a local government may not limit the size of a procurement to only a portion of a known requirement in order to gain advantage of small purchase procedures and then, to fulfill the entire requirement, later issue follow-on change orders that bring the procurement above the simplified acquisition threshold.

FEMA has determined that the Applicant was not required to use sealed bidding for the original procurement and that it was appropriate for the Applicant to have utilized the small purchase procedure method of procurement. When evaluating whether it was appropriate for a local government to have used small purchase procedures, FEMA will review whether the supplies or services to be acquired were initially estimated to not exceed the simplified acquisition threshold or whether the acquisition did, in fact, exceed the threshold. In this case, the Applicant acquired services to repair the single sewer line and sinkhole on Missouri Avenue that cost $86,000, which falls below the simplified acquisition threshold. The documentation provided by the Applicant also indicates that the additional damage discovered after work began on this contract was unknown at the time of the original procurement, and that the Applicant developed the scope for the original procurement based on its inspection of the site and judgment as to the work necessary to repair disaster damage. There is no indication that the Applicant improperly limited a known, larger requirement so as to avail itself of small purchase procedures.

In addition to demonstrating that the acquisition falls below the simplified acquisition threshold, when small purchase procedures are used, a local government must obtain price or rate quotations from an adequate number of qualified sources.[24] FEMA has generally interpreted an “adequate number” of sources under 44 C.F.R. § 13.36(d)(1) to be at least three, although what is adequate will depend upon the facts and circumstances surrounding a particular procurement. [25] The Applicant asserted that it solicited numerous local contractors to submit quotes for the project, with two contractors responding and submitting bids. Although only receiving two bids, the facts and circumstances indicate that it was a reasonable decision not to delay on moving forward with the procurement by going back out and seeking one additional bid from those contractors already solicited or from additional contractors not previously solicited. The Applicant asserted that the water elevation line was above the sewer line at the time the original contract was written. The water, which had a significant and negative effect on the sanitary sewers, manholes, and lift station, made time of the essence to effectuate the repairs and address threats to public health caused by the existing sewer leekage and potential future leekage.[26] FEMA has, under these specific facts and circumstances, determined that the Applicant obtained price or rate quotations from an adequate number of qualified sources for the original procurement.

The Acting Regional Administrator determined in the first appeal that the Applicant failed to adhere to the requirements of 44 C.F.R. § 13.36 when it procured the change order to the original contract, making specific reference to the failure of the Applicant to perform a cost analysis pursuant to 44 C.F.R. § 13.36(f). The first appeal response and analysis, however, did not specifically analyze the method of procurement used to obtain the change order. Notwithstanding, it is implied from the first appeal decision that the Acting Regional Administrator found issue with the Applicant’s noncompetitive method of procuring the change order (as is evidenced by the Applicant and Grantee specifically addressing this issue on second appeal), and FEMA will address this issue as part of the second appeal. The issue of a cost analysis is addressed in the following subsection.

A contract “change” is any addition, subtraction, or modification of work under a contract during contract performance.[27] The first step in analyzing a contract change is to determine whether the change is within the scope of the original procurement. If it is, then the change order is simply part of the original procurement, which means that such a change would be permissible if the Applicant had complied with all relevant procurement standards during the original procurement. FEMA treats a cardinal change, on the other hand, quite differently. A cardinal change is a significant change in contract work (property or services) that causes a major deviation from the original purpose of the work or the intended method of achievement, or causes a revision of contract work so extensive, significant, or cumulative that, in effect, the contractor is required to perform very different work from that described in the original contract.[28] In effect a cardinal change creates a new procurement action that must meet all relevant procurement standards. Cardinal changes cannot be identified by assigning a specific percentage, dollar value, number of changes, or other objective measure that would apply in all cases.

FEMA has determined that the change order at issue comprised a cardinal change to the original contract based on the significant increase to the amount and type of repair work and total cost. The scope of work under the original contract included excavation and repair of the 10-inch line to the east of the manhole and removal and reset of a minimum of the top half of the manhole. The Applicant explained that the depth of the repair work was significantly increased from 16 to 20 feet in the change order and prompted a great deal of additional work, including the excavation and replacement of 12 feet of line west of the manhole, excavation and replacement of 16 feet of line to the north, and placement of a concrete pad beneath the new manhole. The cost of this work increased the costs of the contract by $237,244.86, which is an almost 300% increase to the original fixed-price contract for $86,000.

A contract change that comprises a cardinal change constitutes a sole source award, and FEMA evaluates such a modification to determine if the conditions precedent for a noncompetitive procurement at 44 C.F.R. § 13.36(d)(4) have been met. This regulation does permit a local government to utilize the procurement through noncompetitive proposal method, but only when two conditions precedent are met. The first condition is that the award of contract is infeasible under small purchase procedures, sealed bidding, or competitive proposals, and the second condition precedent is that one of following four alternative conditions apply: (1) the item is available only from a single source; (2) the public exigency or emergency for the requirement will not permit delay resulting from competitive solicitation; (3) the awarding agency authorizes noncompetitive proposals; or (4) after solicitation of a number of sources, competition is determined inadequate. A Public Assistance applicant’s failure to plan does not provide sufficient justification for procurement by noncompetitive proposals or otherwise conducting a procurement through less than full and open competition.

The regulation does not define the term “infeasible,” but FEMA generally defines the term as not feasible, not practicable, or not capable of being done, effected, or accomplished.[29] Whether or not a form of competitive procurement is feasible includes an analysis of the facts and circumstances of a particular procurement and is often intertwined with the analysis of the second condition precedent. The Applicant did not provide any information indicating how long it would have taken to have performed a competitive procurement as part of its first or second appeal. Although no such information was submitted, we understand that the amount of the procurement at issue would have necessitated the Applicant to follow formal advertisement procedures under state law, which requires publication of the advertisement at least ten days before the opening of bids or proposals.[30] FEMA estimates, in the best case, it would also have taken at least 2 weeks to prepare the solicitation, evaluate the bids or proposals upon receipt, resolve any potential protests, prepare a contract, and submit the contract for approval to the cognizant city official(s). FEMA has concluded that it was not feasible to complete the procurement—at the very least—for 3 ½ weeks from the time the Applicant defined the scope of the additional damages on or about November 14, which would be December 8.

FEMA has determined that the Applicant has demonstrated that the public emergency would not permit delay resulting from competitive solicitation. Upon defining the additional damage on or about November 14, repairing the sewer lines without delay was critical, given that the Applicant needed to work immediately to address the existing and potential additional sewage leakage resulting from the damage to the sewer lines and manhole that presented the threat of bacteria and viruses escaping to surrounding areas. The Applicant pointed out that sewer backups continued in the surrounding downtown district and water lines, and that winter temperatures would soon threaten sewage bypass and dewatering operations which would result in the backup of the trunkline, which would have affected homes and businesses. The forthcoming winter temperature would also preclude the ability to actually effectuate the repairs due to freezing of the ground in which the work took place.

FEMA has also determined that the Applicant did not create or otherwise contribute to the public emergency because of the Applicant’s failure to plan. The sinkhole first appeared in June 2011 and the Applicant did not move forward with procuring the original contract to effectuate the permanent repairs until October 2011. It was during the course of these repairs that the Applicant discovered the additional damage and need for significant, additional work, and it was the impending winter temperatures upon which the Applicant has, in part, relied upon in demonstrating the public emergency that precluded delay from a competitive solicitation. As such, if there were no adequate justification for the four-month delay in originally procuring the needed services, then the Applicant could not justify a noncompetitive procurement through its failure to make a timely procurement.

A cost analysis involves the verification of proposed cost data, projections of that data, and evaluation of the specific elements of costs and profits.[35] The Applicant did not provide any documentation that it conducted such an analysis at the time of the change order, meaning that the Applicant failed to meet the requirements of the 44 C.F.R. § 13.36(f)(1). Notwithstanding this noncompliance, FEMA has determined it will exercise its discretion to not take enforcement action under 44 C.F.R. § 13.43.

FEMA has concluded that all work performed under the change order (including replacement of the manhole) is eligible as permanent work under the Public Assistance Program and, in light of this conclusion, must evaluate the costs for eligibility. This includes (1) evaluating the costs for that work the Acting Regional Administrator determined was eligible in the first appeal, but for which he only provided a portion of the requested costs; and (2) evaluating the costs of the additional work that FEMA has determined eligible under this second appeal related to the manhole; and (3) other costs. The Applicant seeks total, additional costs of $249,163.36 under this second appeal as detailed below:

As it relates to work under the change order, the Public Assistance Guide describes the following ways reasonable costs may be established: historic documentation for similar work, average costs for similar work in the area, published unit costs from national cost estimating databases, FEMA cost codes, and equipment rates.[36] The Applicant has provided bid and award amounts and project duration for twelve other disaster-related sewer repair projects captured in other PWs. The average per-day contract award amount was $13,278.57, according to the Applicant’s analysis. In comparison, the initial contract procurement of $86,000.00, with an anticipated project length of seven days, amounted to $12,285.71 per day. The $237,244.86 change order, for work over 25 days, amounted to $9,489.79 per day. The entire $323,244.86 project, which took place over 30 days, averaged $10,744.83 per day, more than $2,500.00 less than the overall per-day average for the Applicant’s sewer repair projects.

FEMA has also independently evaluated the costs for the work performed under the change order.[37] FEMA’s approach of comparing similar work performed in the same city, around the same time frame for damages caused by the same event to determine reasonableness is appropriate and otherwise consistent with the federal cost principles at 2 C.F.R. part. 225.

Based upon the information provided by the Applicant and FEMA’s independent analysis, FEMA has concluded that the additional $213,570.86 for the change order (the $237,244.86 change order amount less the $23,674.00 awarded in the first appeal decision) and additional $3,397.10 for the manhole are eligible for reimbursement. The Applicant also has provided documentation, in the form of vendor invoices, supporting its claim for an additional $2,359.85 for curb and gutter repair and replacement work, and FEMA is also approving the additional costs for such work. Furthermore, FEMA is not taking enforcement action based upon the Applicant’s noncompliance with the procurement standard at 44 C.F.R. § 13.43 by reducing these otherwise eligible costs.

The requested costs for lift station and asphalt repairs are not germane to this appeal, however, as that work was not included in the scope of work for PW 2432, the only PW at issue in this appeal. The Applicant must submit a separate appeal or appeals in order to seek reimbursement for claimed costs not associated with PW 2432. As such, FEMA is denying the requests for additional costs for the lift station and asphalt repairs.

The damage to the three sewer lines and manhole was caused by the disaster event, and the work as described in the change order was necessary to accomplish the needed repairs. The Applicant complied with the method of procurement requirements under 44 C.F.R. § 13.36(d) for both the original procurement and the change order, but failed to comply with the cost analysis requirement for the change order required by 44 C.F.R. § 13.36(f). Notwithstanding this noncompliance, FEMA will exercise its discretion to not take enforcement action by reducing otherwise eligible costs incurred by the Applicant for eligible work. FEMA will, therefore, increase the amount awarded under PW 2432 by an additional $213,570.86 for costs incurred under the change order, $3,397.10 for the manhole, $2,359.85 for curb and gutter repair and replacement, and $5,666.05 for DAC. However, FEMA is denying the requests for additional costs for the lift station and asphalt repairs.

[2] Under FEMA’s calculation, the additional requested amount should be $249,067.82 (the Applicant’s asserted total project costs of $370,612.96, less the original $90,775.33 obligated in PW 2432, the $23,674.00 in additional costs awarded by the Regional Administrator, and $7,095.81 for asphalt repairs associated with the site captured in PW 2425).

[7] SeeFederal Emergency Management Agency, Procurement Disaster Assistance Team, Field Manual – Public Assistance Grantee and Subgrantee Procurement Requirements Under 44 C.F.R. pt. 13 and 2 C.F.R. pt. 215, at 11 (Dec. 2014) [“FEMA PDAT Field Manual”]. See also 48 C.F.R. § 2.101, which defines “full and open competition” with respect to federal acquisitions (“Full and open competition, when used with respect to a contract action, means that all responsible sources are permitted to compete.”).

[22] We note that the Applicant relied upon an emergency procurement authority under state law in conducting its original procurement. S.D. Codified Laws § 5-18A-9. This law provides that “A purchasing agent may make or authorize others to make an emergency procurement without advertising the procurement if rentals are not practicable and there exists a threat to public health, welfare, or safety or for other urgent and compelling reasons.” An emergency procurement “shall be made with such competition as is practicable under the circumstances.” However, even though the Applicant’s original procurement may have complied with state and local law, it must also meet the minimum requirements of the regulation at 44 C.F.R. § 13.36.

[23] The use of small purchase procedures is not required and, if a local government does use this method, it must be consistent with the local government’s procurement procedures which reflect applicable state and local laws and regulations. FEMA has accepted the Applicant’s assertion that the procurement method for the original contract complied with its procurement procedures, such that the only issue addressed in this appeal is whether the method of procurement complied with the federal regulation.

[28] See id. The broader standards applied in Federal contracting practice reflected in Federal court decisions, Federal Boards of Contract Appeals decisions, and Comptroller General decisions provide useful guidance in determining whether a change would be treated as a cardinal change. FEMA does not imply that these Federal procurement decisions are controlling, but FEMA considers the collective wisdom within these decisions in determining the nature of third party contract changes along the broad spectrum between permissible and impermissible changes. For a general overview of the tests used to analyze the permissibility of changes in federal contracts, see John Cibinic, Jr. and Ralph C. Nash, Administration of Government Contracts, 379-, 391, 4th Ed. Chicago: CCH Incorporated, 2006.

[37] To independently evaluate these costs, FEMA did a search for all sewer projects for the City of Pierre, and calculated the average cost per day of the awarded contracts only. The average cost in five awarded contracts was $5,637/day, with a range of $4,095/day to $9,167/day. The contracted cost of the change order pertaining to this PW was $5,649/day, similar to the average.

In the Bulgaria market, you can purchase FEMA 34002-BN-010 with competitive prices and fast delivery options through our experienced sales team.

The FEMA pressure switch DWR controls the pressure of gaseous, vapors, or air fuels in high-pressure systems up to 250 bar. The device is very accurate, factory adjusted and set, and can withstand extreme temperatures. A changeover relay transmits the information to the safety device (gas solenoid valve).

8613371530291

8613371530291