first step act and safety valve in stock

The Federal Safety Valve law permits a sentence in a drug conviction to go below the mandatory drug crime minimums for certain individuals that have a limited prior criminal history. This is a great benefit for those who want a second chance at life without sitting around incarcerated for many years. Prior to the First Step Act, if the defendant had more than one criminal history point, then they were ineligible for safety valve. The First Step Act changed this, now allowing for up to four prior criminal history points in certain circumstances.

The First Step Act now gives safety valve eligibility if: (1) the defendant does not have more than four prior criminal history points, excluding any points incurred from one point offenses; (2) a prior three point offense; and (3) a prior two point violent offense. This change drastically increased the amount of people who can minimize their mandatory sentence liability.

Understanding how safety valve works in light of the First Step Act is extremely important in how to incorporate these new laws into your case strategy. For example, given the increase in eligible defendants, it might be wise to do a plea if you have a favorable judge who will likely sentence to lesser time. Knowing these minute issues is very important and talking to a lawyer who is an experienced federal criminal defense attorney in southeast Michigan is what you should do. We are experienced federal criminal defense attorneys and would love to help you out. Contact us today.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8233847/653535250.jpg)

A “safety valve” is an exception to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. A safety valve allows a judge to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum term if certain conditions are met. Safety valves can be broad or narrow, applying to many or few crimes (e.g., drug crimes only) or types of offenders (e.g., nonviolent offenders). They do not repeal or eliminate mandatory minimum sentences. However, safety valves save taxpayers money because they allow courts to give shorter, more appropriate prison sentences to offenders who pose less of a public safety threat. This saves our scarce taxpayer dollars and prison beds for those who are most deserving of the mandatory minimum term and present the biggest danger to society.

The Problem:Under current federal law, there is only one safety valve, and it applies only to first-time, nonviolent drug offenders whose cases did not involve guns. FAMM was instrumental in the passage of this safety valve, in 1994. Since then, more than 95,000 nonviolent drug offenders have received fairer sentences because of it, saving taxpayers billions. But it is a very narrow exception: in FY 2015, only 13 percent of all drug offenders qualified for the exception.

Mere presence of even a lawfully purchased and registered gun in a person’s home or car is enough to disqualify a nonviolent drug offender from the safety valve,

Even very minor prior infractions (e.g., careless driving) that resulted in no prison time can disqualify an otherwise worthy low-level drug offender from the safety valve, and

Other federal mandatory minimum sentences for other types of crimes – notably, gun possession offenses – are often excessive and apply to low-level offenders who could serve less time in prison, at lower costs to taxpayers, without endangering the public.

The Solution:Create a broader safety valve that applies to all mandatory minimum sentences, and expand the existing drug safety valve to cover more low-level offenders.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62704719/1094199730.jpg.1545184116.jpg)

In December 2018, President Trump signed into law the First Step Act, which mostly involves prison reform, but also includes some sentencing reform provisions.

The key provision of the First Step Act that relates to sentencing reform concerns the “safety valve” provision of the federal drug trafficking laws. The safety valve allows a court to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum sentence for the crime, and to reduce the person’s offense level under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines by two points.

The First Step Act increases the availability of the safety valve by making it easier to meet the first requirement—little prior criminal history. Before the First Step Act, a person could have no more than one criminal history point. This generally means no more than one prior conviction in the last ten years for which the person received either probation or less than 60 days of prison time.

Section 402 of the First Step Act changes this. Now, a person is eligible for the safety valve if, in addition to meeting requirements 2-5 above, the defendant does not have:

John Helms has been a trial lawyer for more than 20 years and is a former federal prosecutor who never lost a trial or appeal. He is the founder of the Law Office of John M. Helms in Dallas, Texas, where he has handled both civil and criminal cases and is skilled at helping clients facing overlapping civil and criminal issues.

This news has been published for the above source. Kiss PR Brand Story Press Release News Desk was not involved in the creation of this content. For any service, please contact https://story.kisspr.com.

Disclaimer: The information does not constitute advice or an offer to buy. Any purchase made from this story is made at your own risk. Consult an expert advisor/health professional before any such purchase. Any purchase made from this link is subject to the final terms and conditions of the website’s selling. The content publisher and its distribution partners do not take any responsibility directly or indirectly. If

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The United States Sentencing Commission made a collective decision to approve its policy priorities for the 2022-2023 amendment year — the top of their list is the First Step Act of 2018, the so-called “compassionate release.”

The First Step Act provides eligible inmates an opportunity to file for compassionate release, under the notion they earn 10 to 15 days of time credit for every 30 days they participate in a program that reduces recidivism. However, this statute has not been added in the guidelines.

Because of this, appellate courts do not feel the U.S. Sentencing Commission’s policy statement presiding over compassionate release applies to the inmates who file for compassionate release. Nonetheless, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to debate about what specifically constitutes a “valid reason” for compassionate release.

Judge Carlton W. Reeves, chair of Commission, said, “The conflicting holdings and varying results across circuits and districts suggest that the courts could benefit from updated guidance from the Commission, which is why we have set this as an important part of our agenda this year.”

As a result, the U.S. Sentencing Commission plans to revise amendments to section 5C1.2 to acknowledge the updated statutory criteria and consider modifications to the 2-level reduction in the drug trafficking guideline that is tied to the statutory safety valve.

In addition, the commission also started to implement criminal provisions contained in the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which includes increased penalties for certain firearms offenses, and other legislative enactments that require Commission action.

To address conflicts and other issues, the Commission published priorities that were not yet definite. In response to this, the commission received more than 8,000 public comments in the form of letters.

“We look forward to a careful and detailed examination of these issues and our continued interaction with the public to ensure the federal sentencing guidelines properly reflect current law and promote uniformity in sentencing,” promised Reeves.

This detailed examination includes addressing key components of the guidelines of the First Step Act. To tackle these conflicts and other issues involving criminal history, there will be projects and programs created to reap benefits of these alternatives-to-incarceration programs.

WASHINGTON, D.C. — The United States Sentencing Commission today unanimously approved its Among its top priorities is implementation of two significant changes made by the First Step Act of 2018.

The First Step Act amended the statute providing for compassionate release to allow defendants for the first time to file for compassionate release, without having the Director of the Bureau of Prisons make a motion. This procedural option is not yet accounted for in the guidelines, leading most appellate courts to hold that the Commission’s policy statement governing compassionate release does not apply to motions filed by defendants. At the same time, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the debate about what constitutes “extraordinary and compelling reasons” for compassionate release took center stage across the nation with differing results.

“The conflicting holdings and varying results across circuits and districts suggest that the courts could benefit from updated guidance from the Commission, which is why we have set this as an important part of our agenda this year,” said Judge Carlton W. Reeves, chair of the Commission.

In addition, the First Step Act made changes to the “safety valve,” which relieves certain drug trafficking offenders from statutory mandatory minimum penalties. The Act expanded eligibility to certain offenders with more than one criminal history point. The Commission intends to issue amendments to section 5C1.2 to recognize the revised statutory criteria and consider changes to the 2-level reduction in the drug trafficking guideline currently tied to the statutory safety valve.

The Commission also set out its intent to implement criminal provisions contained in the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which includes increased penalties for certain firearms offenses, and other legislative enactments that require Commission action.

The Commission published tentative priorities and invited public comment in September, receiving more than 8,000 letters of public comment in response. “The Commission is appreciative of the feedback it has received from all corners of the federal sentencing community,” stated Reeves. “As we now pivot to work on the final priorities set forth today, we look forward to a careful and detailed examination of these issues and our continued interaction with the public to ensure the federal sentencing guidelines properly reflect current law and promote uniformity in sentencing.”

The Commission will also address circuit conflicts, examine other key components of the guidelines relating to criminal history, and begin several multi-year projects, including an examination of diversion and alternatives-to-incarceration programs. “A number of judges and others within the court family expressed strong support for the programs within their own district,” Reeves said. “The Commission looks forward to hearing more from experts and researching more fully the benefits of these programs.”

The Commission will also study case law relating to guidelines commentary and continue its examination of the overall structure of the advisory guideline system post-U.S. v. Booker.

More than a year after it was enacted in 2018, key parts of the law are working as promised, restoring a modicum of fairness to federal sentencing and helping to reduce the country’s unconscionably large federal prison population. But other parts are not, demonstrating the need for continued advocacy and more congressional oversight. The way the Justice Department has been handling prisoner releases during the coronavirus pandemic gives some insight into what’s going wrong.

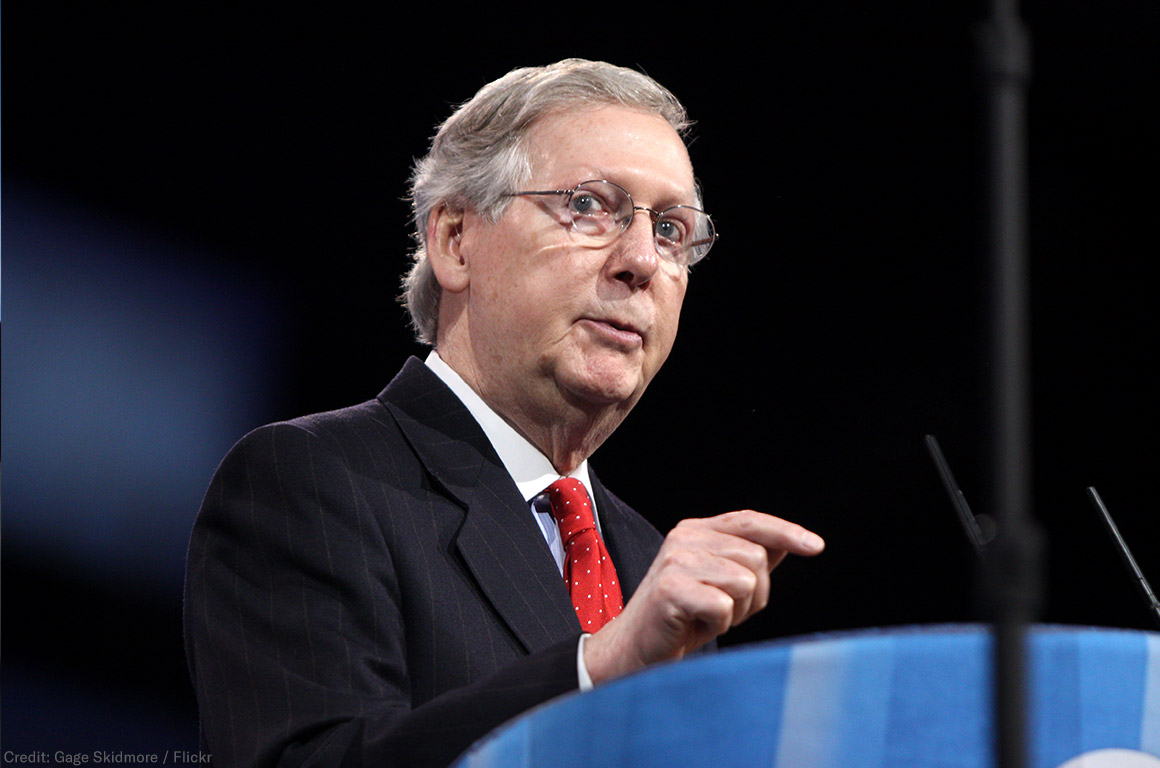

President Trump has bragged about signing the law, which was the first criminal justice reform bill passed in nearly a decade. But simply signing it is not enough. He needs to see it through.

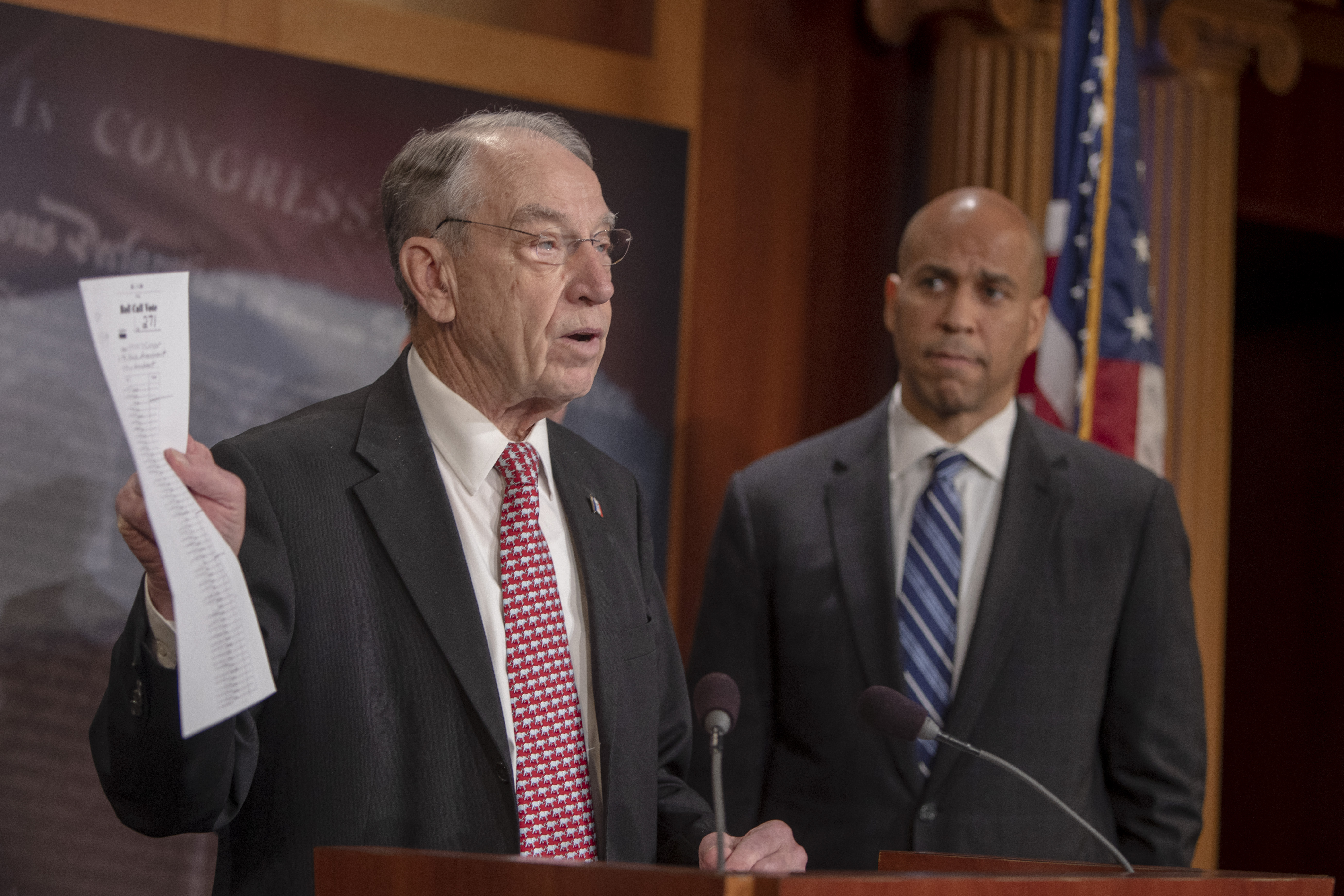

The First Step Act is the product of years of advocacy by people across the political spectrum. Indeed, a very similar bipartisan bill nearly passed in 2015, but was dragged down by election-year politics. The Trump administration began working on its own criminal justice bill in early 2018, and an initial deal was catalyzed by a core group of bipartisan legislators. It was then refined through a series of compromises and, once the Senate decided to pick up the bill, sailed through both houses of Congress with supermajority support.

The law we now know as the First Step Act accomplishes two discrete things, both aimed at making the federal justice system fairer and more focused on rehabilitation.

Its sentencing reformcomponents shorten federal prison sentences and give people additional chances to avoid mandatory minimum penalties by expanding a “safety valve” that allows a judge to impose a sentence lower than the statutory minimum in some cases. These parts of the First Step Act are almost automatic: once the act was signed, judges immediately began sentencing people to shorter prison terms in cases came before them. Similarly, people in federal prison for pre-2010 crack cocaine offenses immediately became eligible to apply for resentencing to a shorter prison term.

The law’s prison reformelements are designed to improve conditions in federal prison in two ways. One is by curbing inhumane practices, such as eliminating the use of restraints on pregnant women and encouraging placing people in prisons that are closer to their families. The other is by reorienting prisons around rehabilitation rather than punishment. That is no small task. Successfully expanding rehabilitative programming in federal prison will require significant follow-through from Congress and the Department of Justice. It’s no surprise, then, that these distinct parts of the act are functioning differently.

Before 2010, an offense involving 5 grams of crack cocaine, a form of the drug more common in the Black community, was punished as severely as one involving 500grams of powder. The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 changed that, reducing this 100:1 disparity to 18:1 — but only on a forward-going basis. People convicted under the now-outdated crack laws were stuck serving the very sentences that Congress had just repudiated.

The First Step Act fixed that by making the Fair Sentencing Act retroactive. According to the Justice Department, as of May, roughly 3,000 people serving outdated sentences for crack cocaine crimes had already been resentenced to shorter prison terms. Shortened or bypassed mandatory minimums mean that every year another estimated 2,000 people will receive prison sentences 20 percent shorter than they would have.

Another 3,100 people were released in July 2019, anywhere from a few days to a few months early, when the First Step Act’s “good time credit fix” went into effect. This simple change allowed people in federal prison to earn approximately an extra week off their sentence per year — and it applied retroactively, too. For some people it meant seeing their friends and family months earlier than expected.

Taken together, these changes represent an important decrease in incarceration. One year after the First Step Act was signed, the federal prison population was around 5,000 people smaller, continuing several years of declines. It has continued to shrink amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

To be sure, there’s still a long way to go: the federal prison population remains sky-high. And the Department of Justice does not appear to be in complete lockstep with the White House’s celebration of the law. In some old crack cocaine cases, federal prosecutors are opposing resentencing motions or seeking to reincarcerate people who have just been released. Prosecutors in these cases argue that any motions for resentencing must also consider the (often higher) amount of the drug the applicant possessed according to presentence reports. Other technical disputes are also cropping up, with the Department of Justice often arguing for a narrow interpretation of the First Step Act.

When it comes to improving programming within federal prison, even more work remains to be done. Federal prisons offer some opportunities for people in prison to participate in services that either address their individual needs, or help prepare them for life after release. Drug treatment and drug education are two examples; others include ESL and educational classes.

The First Step Act calls for the Bureau of Prisons to significantly expand these opportunities. Within a few years, the BOP must have “evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities” available for allpeople in prison. That means vocational training, educational classes, and behavioral therapy (to name a few options recommended in the act) should be staffed and broadly available. Participating in these programs will in turn enable imprisoned people to earn “time credits” that they can put toward a transfer to prerelease custody — that is, a halfway house or even home confinement — theoretically allowing them to finish their sentence outside of a prison.

Rolling out this system as intended will be a challenge, however, in part because BOP programs are already understaffed and underfunded. Around 25 percent of people spending more than a year in federal prison have completed zeroprograms. A recent BOP budget document described a lengthy waiting list for basic literacy programs. And according to the Federal Defenders of New York, the true extent of the BOP’s programming shortfall isn’t even known, because the BOP won’t share information on programming availability or capacity. The bureau offered little insight into its existing capacity and needs at a pair of congressional oversight hearings last fall. Worse, a recent report from the First Step Act’s Independent Review Committee, made up of outside experts to advise and assist the government with implementing the law, casts doubt on the quality of the BOP’s existing programming.

The BOP’s lack of transparency also makes it hard to know how “time credits” are being awarded — and thus, whether the BOP is permitting people to make progress toward prerelease custody as Congress intended. The First Step Act provides that most imprisoned people may earn 10 to 15 days of “time credits” for every 30 days of “successful participation” in recidivism-reduction programming. But a recent report suggests the BOP will award a specific number of “hours” for each program. How many “hours” make up a “day,” for the purpose of awarding credits? This highly technical issue may appear trivial, but could significantly affect the reach of the First Step Act.

People with inside knowledge of the system point to other concerns, too. The law excludes some imprisoned people from earning credits based on the crime that led to their incarceration or their role in the offense, and some advocates report that the BOP has applied those exclusions broadly, disqualifying a much larger part of the imprisoned population than Congress intended. Advocates also have heard that program availability in prisons is much spottier than the BOP has suggested, rendering illusory the DOJ’s claim that people are already being assigned to programs and “productive activities” tailored to their needs.

While some progress is being made, all of these concerns point to a need for more congressional oversight — narrowly focused on the availability and capacity of “recidivism reduction” programming in the BOP.

Any expansion of programming also won’t be free. Knowing that, the First Step Act authorized $75 million per year for five years for implementation. But authorization is only the beginning of the budgeting process. Congress must also formally appropriate money to the BOP to fund the First Step Act for each year that it is authorized.

Thankfully, in December 2019, Congress passed and the president signed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, which included full funding for the First Step Act through the end of the current fiscal year. That makes up for a bumpy start: last year, Congress failed to appropriate anything at all, forcing the DOJ to use $75 million from elsewhere in its budget to cover the temporary shortfall.

While this new funding is good news, it still might not be enough. According to a member of the Independent Review Committee, full implementation may cost closer to $300 million. After factoring in “training, staffing, [and] building things like classrooms,” he says, $75 million simply may not be enough. But any more substantial funding seems unlikely to materialize: in a recent budget, the White House sought nearly $300 million to fund improvements related to the law, of which only $23 million was earmarked for programming.

In late March, the Justice Department appeared to finally acknowledge the need to transfer people in federal prison to home confinement to keep them safe from the coronavirus. But transfers have been slow, and a recent report from ProPublica shows one reason why.

The DOJ prioritized transfers for people deemed to pose a “minimum” risk of recidivism under a new system developed for the First Step Act. But that system, called “PATTERN,” has never been perfect, and appears to have been quietly revised to make it more difficult to reach a “minimum” score — and by extension, that much harder to win a transfer to home confinement. This revelation offers the latest example of how the First Step Act’s implementation has proceeded in fits and starts.

Before imprisoned people can use “time credits” they’ve earned from prison programming, two conditions must be met. First, if they’re seeking a transfer to a halfway house, there must be a bed available. That’s not a sure thing, especially after a round of budget cuts by the Trump administration. Second, an incarcerated person must demonstrate that their risk of committing a new crime is low, as calculated by PATTERN.

The process of developing that tool has not gone smoothly. The first version unveiled by the DOJ, in July 2019, appeared to use a method for calculating “risk” that overstated the actual risk of re-offending among formerly incarcerated people, exaggerated racial disparities, and gave people only marginal credit for completing education, counseling, and other programs while in prison. Taken together, the tool gave short shrift to the idea that people can change while in prison — the very premise of the First Step Act.

Early this year, the DOJ shared what seemed like good news: PATTERN, it said, had been improved to partially address some of the concerns raised by the Brennan Center and others. But the tool continued to use an overly broad definition of recidivism. And while the DOJ claimed it introduced changes to reduce racial disparities, it did not release data on the revised tool’s actual effect on racial disparities. As a result, imprisoned people, families, lawyers, and advocates were all concerned when the DOJ announced it would use PATTERN to help determine who would be transferred out of federal prison during the pandemic.

Those concerns were justified. It now seems that the BOP changed PATTERN more significantly than they initially disclosed to make it much harder to qualify as a “low” or “minimum” risk. (A DOJ report, released a week after ProPublica’s story, suggests that the impact of these changes was relatively small, but offers limited data, and — still — provides no analysis of racial disparities.) This change will certainly narrow the effect of the First Step Act. But more urgently, it seems likely to keep more people in federal prison, exposed to a heightened risk of catching a deadly disease.

Trump has repeatedly claimed credit for passing the First Step Act. He did the same in a Super Bowl ad. Now his administration needs to do the hard work of ensuring that the law lives up to its promise.

Over the years I have been retained by a few criminal defense clients after they had bad experience with a prior lawyer. The reasons for switching defense attorneys in midstream vary: sometimes it is concern over the lawyer’s competence, or concern that their case is not getting the attention it deserves, or even that they just don’t see eye to eye with their lawyer. One of the most common, and disturbing reasons though is that the client feels that their prior attorney ripped them off. These complaints generally involve “flat-fee” retainer agreements in which a lawyer and a client agree upon a fixed sum of money for the entire defense representation no matter whether it goes to trial or ends in a plea deal. I see cases all the time where a lawyer accepts a major felony case for a ridiculously low flat-fee just to land the client. Then, when it becomes obvious the case will require a lot of work, the attorney hits the client up for more money. I have even seen cases where the attorney threatens to withdraw from the case if the client does not come up with the additional funds. I call these “pump and dumps:” The lawyer pumps the client for a quick cash infusion and if the client balks, the lawyer tries to dump the client or the retainer agreement. When this happens, the client rightfully becomes upset and the situation quickly becomes untenable. What should a client do? They have (or should have) a written and enforceable fee agreement with the attorney. Then again, who wants a lawyer defending them from serious criminal charges when they claim they are being paid for their work? Defending clients charged with serious or complex felony cases in state and federal courts takes a great amount of work on the part of the criminal defense attorney, the client, and the defense team. These cases are expensive. To get an idea of how expensive, ask the attorney what their normal hourly fee is. The ask them how many hours they would expect to work in a case such as yours. What if it is a plea? What if it is a trial? If the lawyer’s retainer agreement sounds too good to be true, it probably is. The best thing a person can do when selecting a criminal defense attorney is to deal very clearly with this issue up-front. Hourly fee agreements will avoid the problem altogether. The attorney is paid only for the work performed. When negotiating an hourly fee agreement with a criminal defense attorney, be sure to ask the attorney to give a good faith estimate of the number of hours she or he thinks the case will consume depending on various outcomes like a plea agreement or a trial. If you are negotiating a flat-flee agreement make sure that both parties understand that regardless of how many hours the attorney must spend on the case, the fee agreement spells out the total amount to be paid in attorney fees. To protect both parties, flat fee agreements can be modified to suit the needs of each case. For example: The amount of the fee could be staggered to depend on at what stage of the proceedings the case is resolved: Pre-Indictment, with a plea agreement, after a trial etc. Regardless of the attorney and the fee structure you choose. I always recommend the potential client talk to as many knowledgeable and experienced criminal defense attorneys as the situation allows before settling on their pick. This will give the prospective client some idea of comparable fee agreements and rates. It will also allow both parties to get to know each other a little bit before signing up to work so closely together over so serious a matter. Switching attorneys in the middle of the case is sometimes unavoidable, but it is a situation best-avoided if possible.

Congress passed, and President Trump signed into law, the First Step Act of 2018 in December 2018. Despite the hyperpartisan nature of politics these days, the First Step Act was a bipartisan project several years in the making. The goal of the bipartisan effort was simple but important. It aimed to reduce the number of people in federal prisons while maintaining public safety.

In general, the First Step Act includes three major components. First, it requires the Department of Justice to establish a risk and needs assessment system for the Bureau of Prisons (BOP). Second, it modifies several sentencing provisions for drug-related federal offenses. And third, it reauthorizes the Second Chance Act of 2007 to expand important prison programming. In addition to these three major components, the First Step Act includes a series of other important justice reform measures.

Under the First Step Act, the DOJ must develop a system the BOP can use to assess federal prisoners’ risk of recidivism. During the intake process, the BOP will classify each prisoner as having a minimum, low, medium, or high risk of recidivism. The BOP will also determine each prisoner’s risk of violent or serious misconduct.

Once the BOP determines a prisoner’s risk, it then must assign the prisoner to “evidence-based recidivism reduction programs” and “productive activities” to reduce their risk. The First Step Act tasks prison officials with determining both the type and amount of programming that every prisoner requires, based on the prisoner’s “criminogenic needs.”

As prisoners participate in recidivism reduction programs and productive activities, the BOP is also tasked with reassessing their recidivism risk. If that risk changes — which, assuming the BOP’s programming is worthwhile, should be inevitable — the BOP then must reassign prisoners to new programming based on their updated risk and needs.

Part of the goal behind the First Step Act was to reduce the number of prisoners in federal prisons. According to the BOP, there are more than 150,000 individuals in federal prisons today. The vast majority of that figure (nearly 125,000) are in BOP custody. The remaining amount (roughly 30,000) is split relatively evenly between private facilities and other types of detention centers.

To reduce those numbers, the First Step Act incentivizes participation in recidivism reduction programs. Most notably, prisoners who successfully complete the programming can earn up to 10 days of time credits for every 30 days of program participation. Additionally, minimum- and low-risk prisoners whose assessed risk of recidivism doesn’t increase can earn another five days of time creditors for every 30 days of participation. Altogether, prisoners can earn up to 15 days of time credits for every 30 days of program participation.

Time credits aren’t available for all prisoners, however. In general, prisoners serving sentences for violent crimes, terrorism, espionage, human trafficking, sexual assault and exploitation, repeat felony in possession of a firearm, fraud, or high-level drug offenses can’t earn these time credits. Likewise, prisoners subject to a final order of removal by a U.S. Immigration Court also aren’t eligible. These prisons may be, however, eligible for other incentives under the First Step Act.

The First Step Act also incentivizes prisoner participation with other rewards. These include additional phone privileges, including an extra 30 minutes per day. They also include additional visitation time and the possibility of a transfer to a facility closer to home. Other examples include increased spending limits and product offerings for commissary as well as greater email access. Prisoners could also earn placement in preferred housing units. Finally, the act even allows for other rewards that prisoners propose — so long as the BOP approves.

Some prisoners may not be able to meet this final requirement. They can, however, be transferred to prerelease custody if the warden determines that they are not a danger to society. The warden must also believe that they have made good faith attempts to lower their recidivism risk and are unlikely to reoffend.

Prerelease custody ordinarily includes home confinement with 24-hour electronic monitoring and a variety of other conditions. In general, individuals in prerelease custody must remain in their home with some limited exceptions:

If individuals in prerelease custody comply with their conditions, the BOP is required to reduce the restrictiveness of those conditions. If, on the other hand, a person violates their conditions, the BOP can impose additional restrictions or even revoke prerelease custody and return the person to prison to finish their term. And, if someone in prerelease custody commits a new crime, the BOP also must revoke their prerelease custody status.

First, the First Step Act reduced mandatory minimums for some drug-trafficking offenses where the offender had at least one prior conviction. If the offender has only one prior conviction, the First Step Act reduced the mandatory minimum from 20 years to 15 years. If the offender has two or more prior convictions, the First Step Act reduced it from a life sentence to a 25-year mandatory minimum.

The First Step Act also changed the criteria that courts use to determine whether a prior conviction triggers these mandatory minimum sentence rules. Rather than simply requiring a felony drug offense, the First Step Act requires that a prior conviction constitute a “serious drug felony” or “serious violent felony.” Serious drug felonies must carry a maximum of 10 years or more, and the individual must have served more than 12 months on that conviction within the past 15 years.

This is a significant change from the prior standard, which merely required a drug felony, because that only required a prior conviction of a drug offense with a maximum term of one year or more. Serious violent felonies similarly require that the individual must have served at least 12 months in prison.

The First Step Act also expands the “safety valve” provision that previously applied to offenders without a criminal record. This safety valve provision allows judges to sentence low-level, nonviolent drug offenders to a term of imprisonment that is less than the mandatory minimum that would ordinarily apply. Now, under the act, that safety valve provision applies to drug offenders with minor criminal records as well.

Before the First Step Act, someone convicted of two or more drug-trafficking offenses involving a firearm in the same case could be subject to the “stacking” provision. This means that they would face a 25-year minimum for two or more convictions. This was true even though those convictions were the product of charges in the same case. Under the First Step Act, however, the “stacking” provision applies only when the individual has a priorconviction.

The First Step Act retroactively applies the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act. Now, prisoners serving sentences for crimes involving crack cocaine can petition to have their sentences reduced. The Fair Sentencing Act’s provisions specifically addressed the disparity in sentences for powder and crack cocaine.

Originally, someone convicted of possessing 50 grams of crack cocaine faced the same 10-year minimum that someone convicted of possessing 5,000 grams of powder cocaine did. The same disparity existed with five-year minimums, too: Five grams of crack cocaine got you the same sentence as 500 grams of powder cocaine. With the Fair Sentencing Act, the crack-to-power ratio went from five to 500 (or 50 to 5,000) to 28 to 500 (or 280 to 5,000).

Lastly, the First Step Act creates the Second Chance Reauthorization Act of 2018. That provision reauthorizes a number of grant programs first authorized by the Second Chance Act of 2007. Examples of reauthorized programs include the following:

Treatment, grant programming and research provided for under the Second Chance Reauthorization Act of 2018 aims to improve the quality of life for prisoners both in and out of prison. Whether the act achieves this goal is a subjective question. But the act also includes provisions requiring the National Institute of Justice to evaluate its effectiveness within five years.

The First Step Act also contains several other provisions aimed at reforming the criminal justice system as well. Perhaps the best example is the act’s amendment to 18 U.S.C. § 3624(b). Now, prisoners can now earn up to 54 days of good time credit for every year of their sentence imposed. Under the law’s previous version, good time credit was based on time served.

Other examples include a prohibition on the use of restraints on pregnant prisoners, the placement of prisoners closer to their primary residence, and the placement of low-risk prisoners in home confinement. They also include more flexibility and transparency when it comes to compassionate release, the expansion of prisoner employment, de-escalation training for prison officials, and more.

The First Step Act undoubtedly includes many positive measures aimed at reforming the criminal justice and prison systems. But the provisions in the bill are only an improvement to the extent that they impact BOP’s practices. And, so far, the First Step Act’s major reforms are getting mixed reviews at best.

Perhaps the most significant criticism so far centers on the First Step Act’s provision providing for 15 days of time credits for every 30 days of programming. On the surface, the 30-15 provision makes it sound relatively straightforward to earn time credits. Your mind automatically breaks it down into months: do 12 months of programming, and you get out six months early. Undoubtedly it won’t be that simple, we think, but it’s something to aim for.

But a recent report from the Federal Bureau of Prisons gives a different impression. The report reflects some programs provide an opportunity for a significant amount of hours on a somewhat regular basis. For example, the “Bureau Literacy Program” is 240 hours and one and a half hours per day.

Other programs, however, are shorter and less frequent. Two female-only programs, “Assert Yourself for Female Offenders” and “Understanding Your Feelings: Shame and Low Self Esteem,” are only eight- and seven-week programs. And they are also only available on a one-hour-per-week basis, meaning you’d only earn eight or seven hours over the course of roughly two months.

It isn’t just the frequency and length of the programs in the report that raise questions. There are numerous other questions advocates have been asking since the Bureau released it.

For example, how many “hours” constitutes a day under the First Step Act? If it’s eight hours per day, you’d complete one day of programming once you completed the eight-week “Assert Yourself for Female Offenders.” Only 29 more programs just like it, and you’d have 15 days worth of “time credits.” If you were only allowed to participate in one program at a time — something else that isn’t perfectly clear — it would take you 232 weeks to earn 15 days with one-hour-a-week programs like “Assert Yourself for Female Offenders.”

And this is just one potential issue with the First Step Act as implemented by the Bureau of Prisons. Other problems include how the Bureau has applied the law’s exclusions with respect to some prisoners. Some advocates contend that the Bureau has applied the exclusions too broadly. In doing so, the BOP disqualifies a much larger portion of the prison population than ever intended. Advocates also fear that the availability of programming is much spottier than the law requires.

Critics also worry about the impact the First Step Act might have on racial, ethnic and religious minorities. It should be emphasized that even critics of the First Step Act recognize the need for significant reform measures to the criminal justice system. And they even praise some of the fundamental aspects of the First Step Act itself. But that doesn’t take away their concerns.

As indicated above, the First Step Act implements risk assessment tools. Throughout U.S. history, discretionary assessment tools used in the criminal justice system have routinely relied on racially-biased factors. The fear is that the risk assessment tools for the 30-15 program won’t be any different. Rather than using “tools” like algorithms, critics recommend systems that required individualized assessments. These present a better chance of accurately determining one’s recidivism risk.

Critics also point out that the First Step Act penalizes prisoners based on their immigration status. Several provisions in the act expressly exclude non-citizen immigrants, including ones that help prisoners earn an early release. Yet immigration-related cases make up more than 50% of all federal criminal prosecutions.

The First Step Act also appears to encourage participation in religious programming in prison. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits Congress from making “law[s] respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof….” Yet the First Step Act expressly includes “faith-based classes or services” in the definition of evidence-based recidivism reduction program. This means that participation in faith-based classes or services can earn prisoners an early release. In light of the inadequate availability of programming, prisoners may feel pressured to participate in programming for faiths they don’t believe in just to earn time credits. This pressure is both constitutionally problematic and simply immoral.

The First Step Act of 2018 is significant. It marks one of the most notable steps at reforming the criminal justice system in recent memory. But the act itself is — as its name suggests — just a first step. And even that first step was far from perfect. Moving forward, it is incumbent on lawmakers to amend the First Step Act. They need to address the problems laid out above as well as many, many more. But it’s also incumbent on them to take additional steps, too. But, as Senator Cory Book (D-NJ) likes to say, lawmakers must be able to “walk and chew bubble gum at the same time.”

In federal cases, Congress not only defines what is a crime that can cost the accused both freedom and property, but it also passes statutes that control how federal judges are allowed to sentence those who have been convicted of federal drug crimes. For instance, federal judges must follow the United States Sentencing Guidelines when sentencing someone upon conviction of a federal crime. For more on sentencing guidelines and how they work, read our discussion in Federal Sentencing Guidelines: Conspiracy To Distribute Controlled Substance Cases.

Sometimes, Congress sets a bottom line on the number of years someone must spend behind bars upon conviction for a specific federal crime. The federal judge in these situations has no discretion: he or she must follow the Congressional mandate.

These are called “mandatory minimums” in sentencing. They are commonly applied in federal drug cases in here Texas and elsewhere across the country. For more detail, read Mandatory Minimum Penalties in Federal Sentencing.

Of course, there are a tremendous number of federal laws that define federal drug crimes. For purposes of illustration, consider those federal drug crimes that come with either (1) a sentence of 10 years to life imprisonment or (2) those that come with a sentence of 5 to 40 years behind bars, both defined as the mandatory sentences to be given upon conviction for these defined federal drug crimes.

For reference, these refer to the statutory language of 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A) and 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B), which instruct the federal judge on how he or she shall sentence anyone convicted of the manufacture, distribution, or dispensing of a controlled substance (i.e., an illegal drug) or possession with intent to either of these things.

Key here: the judge is given the mandatory minimum number of years that the accused must spend behind bars by Congress via the federal statutory language. A federal judge cannot go below ten (10) years for a federal drug crime based upon 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A). He or she cannot go below five (5) years for a federal drug crime conviction based upon 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B).

How do you know if you are charged with one of these federal drug crimes that come with a mandatory minimum sentence of either 5-to-40 years (a “b1B” case) or 10-to-life (a “b1A” case)? Read the language of your Indictment. It will specify the statute’s citation. If you do not have a copy of your Indictment, please feel free to contact my office and we can provide you a copy.

Can’t there be any way to get around that set-in-stone bottom line? Yes. There is also a statutory exception which allows the federal judge to dip below that mandatory minimum number of years in some situations. It is called the “Safety Valve” defense.

Congress has passed another law that provides for an exception to the instructions given to federal judges on the mandatory minimum sentences that must be given according to Congressional mandate.

The law, 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), provides for an exception that allows the federal judge some leeway in drug crime convictions where he or she would otherwise be required to follow the mandatory minimum sentencing statute. This is the Safety Value statute. It states as follows:

(f)Limitation on Applicability of Statutory Minimums in Certain Cases.—Notwithstanding anyother provision of law, in the case of an offense under section 401, 404, or 406 of theControlled Substances Act(21 U.S.C. 841, 844, 846), section 1010 or 1013 of theControlled Substances Import and Export Act(21 U.S.C. 960, 963), or section 70503 or 70506 of title 46, the court shall impose a sentence pursuant to guidelines promulgated by the United States Sentencing Commission undersection 994 of title 28without regard to any statutory minimum sentence, if the court finds at sentencing, after the Government has been afforded the opportunity to make a recommendation, that—

(4)the defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager, or supervisor of others in the offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise, as defined in section 408 of theControlled Substances Act; and

(5)not later than the time of the sentencing hearing, the defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

The only way to allow for this exception to be applied in a federal sentencing hearing is for the defense to argue its application and to provide authenticated and admissible support for use of the Safety Valve.

How does the defense do this? It takes much more than referencing the exception to the general rule itself. The defense will have to demonstrate the convicted defendant meets the Safety Valve’s five (5) requirements.

Federal sentencing has its own reference manual that is used throughout the United States, called the United States Sentencing Guidelines (“USSG”). We have gone into detail about the USSG and its applications in earlier discussions; to learn more, read:

Essentially, the accused can be charged with a three-point offense; a two-point offense; or a one-point offense. The number of points will depend on things like if it is a violent crime; violent crimes get more points than non-violent ones. The higher the overall number of points, and the ultimate total score, then the longer the sentence to be given under the USSG.

For a successful safety valve defense, the defense has to show that the total Criminal History Points are four (4) or less. If you have a maximum of four Criminal History points, you have met the first criteria for the safety valve.

Note: prior to the passage of the First Step Act, things were much harsher. If the defense had even two Criminal History Points, then the accused was ineligible for the safety valve. The First Step Act increased the number of points, or score, from one to four as the maximum allowed for application of the safety valve. For more on the First Step Act, see The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 1 of 2 and The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 2 of 2.

Looking at the Safety Valve statute ( 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)), the second step in achieving application of the safety valve defense involves the circumstances of the underlying criminal activity and whether or not it involved violence of threats or violence, or if the defendant possessed a firearm at the time.

It has been my experience that it is pretty common for there to be a firearm of some sort involved in a federal drug crime prosecution. Here, the impact of Texas being a part of the Fifth Judicial District for the United States Court of Appeals (“Fifth Circuit”) is important.

This is because this overseeing federal appeals court has looked at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) and its definition of possession of a firearm, and come to a different conclusion that the definition given in the USSG.

In the USSG, two points are given (“enhanced”) for possessing a firearm in furtherance of a federal drug trafficking offense. See, USSG §2D1.10, entitled Endangering Human Life While Illegally Manufacturing a Controlled Substance; Attempt or Conspiracy.

Meanwhile, the Fifth Circuit has ruled that under the Safety Valve Statute, the standard for the government is much higher. According to their ruling, in order to be disqualified from application of the safety valve because of possession of a firearm, the defendant has to have been actually in possession of the firearm or in construction possession of it. See, US v. Wilson, 105 F.3d 219 (5th Cir. 1997).

Consider how this works in a federal drug crime conspiracy case. Under the USSG, a defendant can receive two (2) points (“enhancement”) for possession of a firearm even if they never had their hands on the gun. As long as a co-conspirator (co-defendant) did have possession of it, and that possession was foreseeable by the defendant, then the Sentencing Guidelines allow for a harsher sentence (more points).

The position of the Fifth Circuit looks upon this situation and determines that it is one thing for the defendant to have possession of the firearm, and another for there to be stretching things to cover constructive possession when he or she never really had the gun.

This is the example of the importance of effective criminal defense representation, where research reveals that it is easier to achieve a safety valve defense with a reference to case law. The Fifth Circuit allows a situation where someone can get two (2) points under the USSG (“enhancement”) and still be eligible for the safety valve defense.

The commentary to § 5C1.2(2) provides that “[c]onsistent with [U.S.S.G.] § 1B1.3 (Relevant Conduct),” the use of the term “defendant” in § 5C1.2(2) “limits the accountability of the defendant to his own conduct and conduct that he aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused.” See U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2, comment. (n.4). This language mirrors § 1B1.3(a)(1)(A). Of import is the fact that this language omits the text of § 1B1.3(a)(1)(B) which provides that “relevant conduct” encompasses acts and omissions undertaken in a “jointly undertaken criminal activity,” e.g. a conspiracy.

Being bound by this commentary, we conclude that in determining a defendant’s eligibility for the safety valve, § 5C1.2(2) allows for consideration of only the defendant’s conduct, not the conduct of his co-conspirators. As it was Wilson’s co-conspirator, and not Wilson himself, who possessed the gun in the conspiracy,the district court erred in concluding that Wilson was ineligible to receive the benefit of § 5C1.2. Because application of § 5C1.2 is mandatory, see U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2 (providing that the court “shall” impose a sentencing without regard to the statutory minimum sentence if the defendant satisfies the provision’s criteria), we vacate Wilson’s sentence and remand for resentencing.

The defense must also be able to prove that the defendant’s role in the underlying criminal offense did not result in the death or bodily injury of someone else to achieve the safety valve defense under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f).

In drug cases, this can mean more than some type of violent scenario. The mere type of drug or controlled substance involved can impact the success of this defense. Sometimes, the drugs themselves are the type that can cause severe harm or death. Several controlled substances can be lethal. In a federal drug case, there is a special definition for death resulting from the distribution of a controlled substance.

If the defense can prove with authenticated and admissible evidence that the defendant did not distribute a drug or controlled substance that ended up with someone’s death, or severe bodily injury, then the safety valve defense will be available to them.

Role adjustments happen when someone is alleged to be involved in a conspiracy, and they act in some type of position of responsibility. They can be a leader, or organizer, or somebody who supervises other people in the operations, all as defined in the USSG.

If the defendant was deemed to meet one of these definitions, and had some kind of role involving responsibility or power in the illegal drug operations, then the USSG will add points (“enhance”) as a “role adjustment.”

If you are to achieve the safety valve defense, you cannot receive any “role adjustment” under the Sentencing Guidelines. This must be established to the court by your defense attorney at the sentencing.

Finally, under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) the defense must show that the defendant has given a full and complete statement to the authorities. Specifically, the statute requires a showing that:

The defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

I realize that for many people, this language brings with it the assumption that the defendant has to be a snitch in order to meet this requirement for the safety valve defense. This is not true.

With an experienced criminal defense lawyer, what it does mean is that the defendant has a meeting with the authorities with the goal of meeting the Safety Valve Statute requirements and no more.

The attorney can limit the scope of the meeting. He or she can make sure that law enforcement follows the rules for the meeting. The meeting is necessary for the defendant to achieve a safety valve defense, so there is no way to avoid a safety valve interview.

To get the sentence that is below the mandatory minimum sentence, the meeting is a must. However, it is not a free-for-all for the government where the defendant is ratting on other people.

I arranged for my client to have his safety valve meeting as well as establishing the other criteria needed for application of the Safety Valve statute. I was present at the meeting. There was no cooperation regarding the other defendants, and he did nothing more than the minimum to qualify for the defense. He was no snitch.

As a result, the safety valve was applied by the federal judge and my client achieved a safety valve application where he was sentenced to 8 years for distribution of meth: well below the 10 years of the mandatory minimums and the USSG calculation in his case of around 14 years.

Sadly, the same day that my client was sentenced, so were several of the co-conspirator defendants. I was aware that they were also eligible for the safety valve defense. However, the federal agent at the sentencing hearings that day told me that their lawyers never contact the government for a safety valve meeting.

They were never debriefed, so they could not meet the requirements for application of the safety value statute. The judge had no choice –they each had to be sentenced to the mandatory minimum sentences under the law.

8613371530291

8613371530291