first step act safety valve eligibility brands

The Federal Safety Valve law permits a sentence in a drug conviction to go below the mandatory drug crime minimums for certain individuals that have a limited prior criminal history. This is a great benefit for those who want a second chance at life without sitting around incarcerated for many years. Prior to the First Step Act, if the defendant had more than one criminal history point, then they were ineligible for safety valve. The First Step Act changed this, now allowing for up to four prior criminal history points in certain circumstances.

The First Step Act now gives safety valve eligibility if: (1) the defendant does not have more than four prior criminal history points, excluding any points incurred from one point offenses; (2) a prior three point offense; and (3) a prior two point violent offense. This change drastically increased the amount of people who can minimize their mandatory sentence liability.

Understanding how safety valve works in light of the First Step Act is extremely important in how to incorporate these new laws into your case strategy. For example, given the increase in eligible defendants, it might be wise to do a plea if you have a favorable judge who will likely sentence to lesser time. Knowing these minute issues is very important and talking to a lawyer who is an experienced federal criminal defense attorney in southeast Michigan is what you should do. We are experienced federal criminal defense attorneys and would love to help you out. Contact us today.

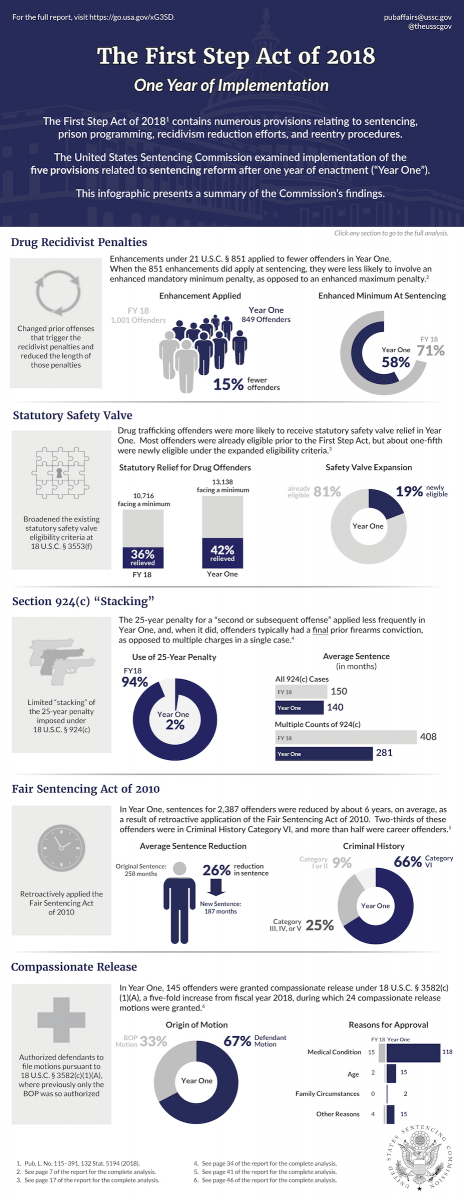

In December 2018, President Trump signed into law the First Step Act, which mostly involves prison reform, but also includes some sentencing reform provisions.

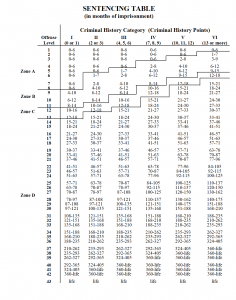

The key provision of the First Step Act that relates to sentencing reform concerns the “safety valve” provision of the federal drug trafficking laws. The safety valve allows a court to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum sentence for the crime, and to reduce the person’s offense level under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines by two points.

The First Step Act increases the availability of the safety valve by making it easier to meet the first requirement—little prior criminal history. Before the First Step Act, a person could have no more than one criminal history point. This generally means no more than one prior conviction in the last ten years for which the person received either probation or less than 60 days of prison time.

Section 402 of the First Step Act changes this. Now, a person is eligible for the safety valve if, in addition to meeting requirements 2-5 above, the defendant does not have:

This news has been published for the above source. Kiss PR Brand Story Press Release News Desk was not involved in the creation of this content. For any service, please contact https://story.kisspr.com.

Congress changed all of that in the First Step Act. In expanding the number of people covered by the safety valve, Congress wrote that a defendant now must only show that he or she “does not have… (A) more than 4 criminal history points… (B) a prior 3-point offense… and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense.”

The “safety valve” was one of the only sensible things to come out of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the bill championed by then-Senator Joe Biden that, a quarter-century later, has been used to brand him a mass-incarcerating racist. The safety valve was intended to let people convicted of drug offenses as first-timers avoid the crushing mandatory minimum sentences that Congress had imposed on just about all drug dealing.

Eric Lopez got caught smuggling meth across the border. Everyone agreed he qualified for the safety valve except for his criminal history. Eric had one prior 3-point offense, and the government argued that was enough to disqualify him. Eric argued that the First Step Actamendment to the “safety valve” meant he had to have all three predicates: more than 4 points, one 3-point prior, and one 2-point prior violent offense.

Last week, the 9th Circuit agreed. In a decision that dramatically expands the reach of the safety valve, the Circuit applied the rules of statutory construction and held that the First Step amendment was unambiguous. “Put another way, we hold that ‘and’ means ‘and.’”

“We recognize that § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language might be viewed as a considerable departure from the prior version of § 3553(f)(1), which barred any defendant from safety-valve relief if he or she had more than one criminal-history point under the Sentencing Guidelines… As a result, § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language could possibly result in more defendants receiving safety-valve relief than some in Congress anticipated… But sometimes Congress uses words that reach further than some members of Congress may have expected… We cannot ignore Congress’s plain and unambiguous language just because a statute might reach further than some in Congress expected… Section 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language, the Senate’s own legislative drafting manual, § 3553(f)(1)’s structure as a conjunctive negative proof, and the canon of consistent usage result in only one plausible reading of § 3553(f)(1)’s“and” here: “And” is conjunctive. If Congress meant § 3553(f)(1)’s “and” to mean “or,” it has the authority to amend the statute accordingly. We do not.”

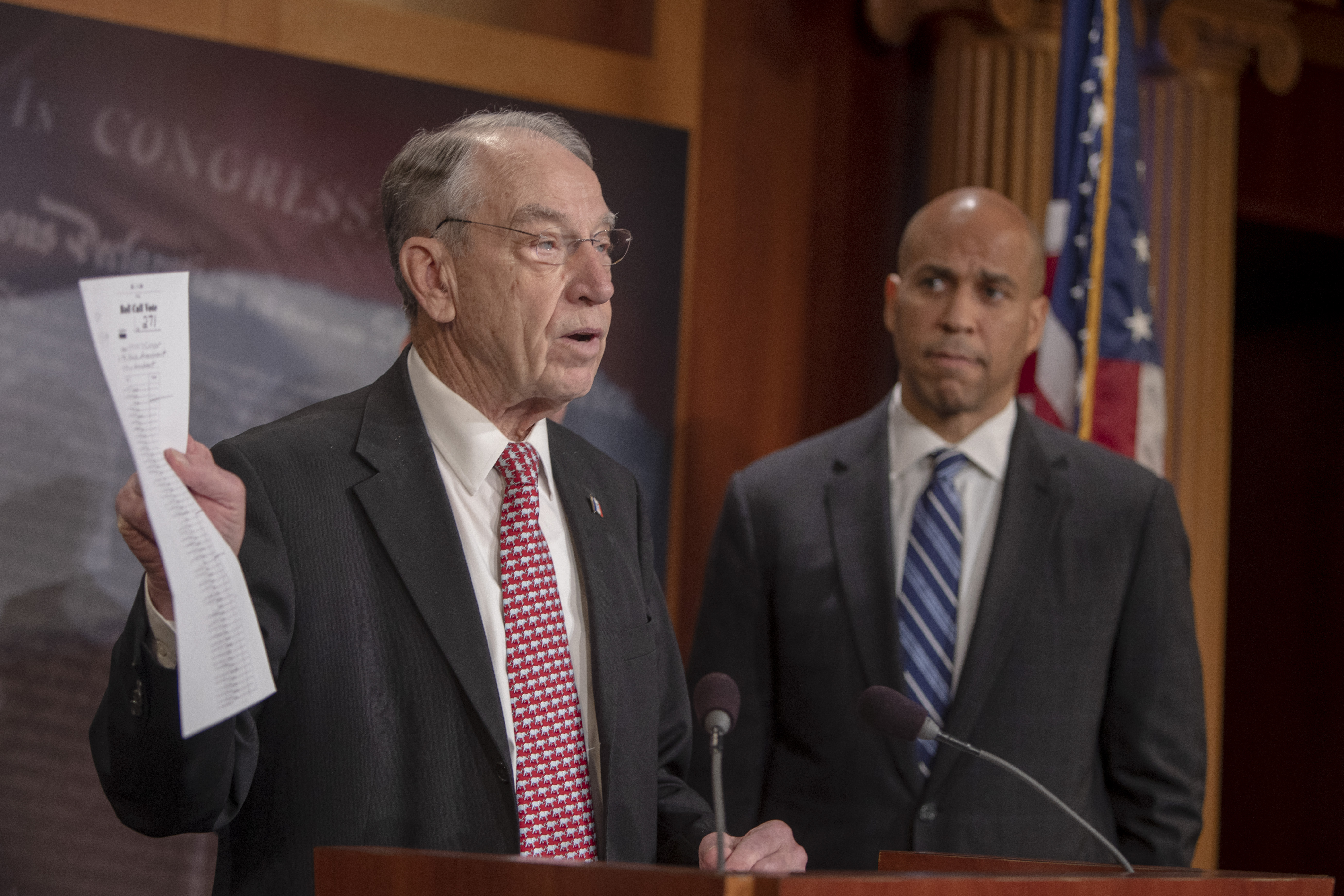

On behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, we write to urge you to vote YES on S. 756, the FIRST STEP Act. This legislation is a next step towards desperately needed federal criminal justice reform, but for all its benefits, much more needs to be done. The inclusion of concrete sentencing reforms in the new and improved Senate version of the FIRST STEP Act is a modest improvement, but many people will be left in prison to serve long draconian sentences because some provisions of the legislation are not retroactive. The revised FIRST STEP Act, however, is not without problems. The bill continues to exclude individuals from benefiting from some provisions based solely on their prior offenses, namely citizenship and immigration status, as well as certain prior drug convictions and their “risk score” as determined by a discriminatory risk assessment system. While these concerns remain a priority for our organizations and we will advocate for improvements in the future, ultimately the improvements to the federal sentencing scheme will have a net positive impact on the lives of some of the people harmed by our broken justice system and we urge you to vote YES on S. 756. The ACLU and The Leadership Conference will include your votes on our updated voting scorecards for the 115th Congress.

While the dollar amounts are astounding, the toll that our U.S. criminal justice policies have taken on black and brown communities across the nation goes far beyond the enormous amount of money that is spent. This country’s extraordinary incarceration rates impose much greater costs than simply the fiscal expenditures necessary to incarcerate over 20 percent of the world’s prisoners. The true costs of this country’s addiction to incarceration must be measured in human lives and particularly the generations of young black and Latino men who serve long prison sentences and are lost to their families and communities. The Senate version of the FIRST STEP Act makes some modest improvements to the current federal system.

I. Sentencing Reform Changes to House-passed FIRST STEP Act–Sentencing reform is the key to slowing down the flow of people going into our prisons. This makes sentencing reform pivotal to addressing mass incarceration, prison overcrowding, and the exorbitant costs of incarceration. As a result of our coalition’s advocacy, the new FIRST STEP Act added some important sentencing reform provisions from SRCA, which will aid us in tackling these issues on the federal level.[x] These important changes in federal law will result in fewer people being subjected to harsh mandatory minimums.

Expands the Existing Safety Valve. The revised bill expands eligibility for the existing safety valve under 18 U.S.C 3553(f)[xi] from one to four criminal history points if a person does not have prior 2-point convictions for crimes of violence or drug trafficking offenses and prior 3-point convictions. Under the expanded safety valve, judges will have discretion to make a person eligible for the safety valve in cases where the seriousness of his or her criminal history is over-represented, or it is unlikely he or she would commit other crimes. This crucial expansion of the safety valve will reduce sentences for an estimated 2,100 people per year.[xii]

Retroactive Application of Fair Sentencing Act (FSA). The new version of FIRST STEP Act would retroactively apply the statutory changes of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (FSA), which reduced the disparity in sentence lengths between crack and powder cocaine. This change in the law will allow people who were sentenced under the harsh and discriminatory 100 to 1 crack to powder cocaine ratio to be resentenced under the 2010 law.[xiii] This long overdue improvement would allow over 2,600 people the chance to be resentenced.[xiv]

Reforms the Unfair Two-Strikes and Three-Strikes Laws. The new version of FIRST STEP would reduce the impact of certain mandatory minimums. It would reduce the mandatory life sentence for a third drug felony to a mandatory minimum sentence of 25 years and reduce the 20-year mandatory minimum for a second drug felony to 15 years.

II. Prison Reform Changes to House-passed FIRST STEP Act, H.R. 3356–The revised bill also made some strides in improving some of the problematic prison reform provisions. The new bill strengthened oversight over the new risk assessment system, limited the discretion of the attorney general, and increased funding for prison programming, among other things. The bill now does the following:

Permits Early Community Release and Loosens Restrictions on Home Confinement.The House-passed FIRST STEP Act limited the use of earned credits to time in prerelease custody (halfway house or home confinement). The revised bill would expand the use of earned credits to supervised release in the community. The bill also would permit individuals in home confinement to participate in family-related activities that facilitate the prisoner’s successful reentry.

Limits Discretion to Deny Early Release.The revised bill strikes language giving the BOP Director and/or the prison warden broad discretion to deny release to individuals who meet all eligibility criteria.

Reauthorizes Second Chance Act. The revised bill reauthorizes the Second Chance Act, which provides federal funding for drug treatment, vocational training, and other reentry and recidivism programming.

While these revisions to the bill were critical to garnering our support, we must acknowledge that some of the more concerning aspects of the House-passed version of the FIRST STEP Act remain.

III. Outstanding Concerns Regarding the FIRST STEP Act–The bill continues to exclude too many people from earning time credits, including those convicted of immigration-related offenses. It does not retroactively apply its sentencing reform provisions to people convicted of anything other than crack convictions, continues to allow for-profit companies to benefit off of incarceration, fails to address parole for juveniles serving life sentences in federal prison, and expands electronic monitoring.

Fails to Include Retroactivity for Enhanced Mandatory Minimum Sentences for Prior Drug Offenses &. 924(c) “stacking.”The bill does not include retroactivity for its sentencing reforms besides the long-awaited retroactivity for the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010. This minimizes the overall impact substantially. Retroactivity is a vital part of any meaningful sentencing reform. Not only does it ensure that the changes we make to our criminal justice system benefit the people most impacted by it, but it’s also one of the essential policy changes to reduce mass incarceration. The federal prison population has fallen by over 38,000[xvi] since 2013 thanks in large part to retroactive application of sentencing guidelines approved by the U.S. Sentencing Commission.[xvii] More than 3,000 people will be left in prison without retroactive application of the “three strikes” law and the change to the 924 (c) provisions in the FIRST STEP Act.[xviii]

Excludes Too Many Federal Prisoners from New Earned Time Credits. The bill continues to exclude many federal prisoners from earning time credits and excludes many federal prisoners from being able to “cash in” the credits they earn. The long list of exclusions in the bill sweep in, for example, those convicted of certain immigration offenses and drug offenses.[xix] Because immigration and drug offenses account for 53.3 percent of the total federal prison population, many people could be excluded from utilizing the time credits they earned after completing programming.[xx] The continued exclusion of immigrants from the many benefits of the bill simply based on immigration status is deeply troubling. The Senate version of FIRST STEP maintains a categorical exclusion of people convicted of certain immigration offenses from earning time credits under the bill. The new version of the bill also bars individuals from using the time credits they have earned if they have a final order of removal. More than 12,000 people are currently in federal prison for immigration offenses and are disproportionately people of color.[xxi] Thus, a very large number of people in federal prison would not reap the benefits proposed in this bill and a disproportionate number of those excluded would be people of color. Denying early-release credits to certain people also reduces their incentive to complete the rehabilitative programs and contradicts the goal of increasing public safety. Any reforms enacted by Congress should impact a significant number of people in federal prison and reduce racial disparities or they will have little effect on the fiscal and human costs of incarceration.

Allows Private Prison Companies to Profit. The bill also maintains concerning provisions that could privatize government functions and allow the Attorney General excessive discretion. FIRST STEP provides that in order to expand programming, BOP shall enter into partnerships with private organizations and companies under policies developed by the Attorney General, “subject to appropriations.” This could result in the further privatization of what should be public functions and would allow private entities to unduly profit from incarceration.

Fails to Include Parole for Juveniles, Sealing and Expungement. Under SRCA, judges would have discretion to reduce juvenile life without parole sentences after 20 years. It would also permit some juveniles to seal or expunge non-violent convictions from their record. The FIRST STEP Act does not address these important bipartisan provisions.

Bringing fairness and dignity to our justice system is one of the most important civil and human rights issues of our time. The revised version of the FIRST STEP Act is a modest, but important move towards achieving some meaningful reform to the criminal legal system. While the bill continues to have its problems, and we will fight to address those in the future, it does include concrete sentencing reforms that would impact people’s lives. For these reasons, we urge you to vote YES on S. 756.

Ultimately, the First Step Act is not the end– it is just the next in a series of efforts over the past 10 years to achieve important federal criminal justice reform. Congress must take many more steps to undo the harms of the tough on crime policies of the 80’s and 90’s – to create a system that is just and equitable, significantly reduces the number of people unnecessarily entering the system, eliminates racial disparities, and creates opportunities for second chances.

If you have any additional questions, please feel free to contact Jesselyn McCurdy, Deputy Director, ACLU Washington Legislative Office, at [email protected] or (202) 675-2307 or Sakira Cook, Director, Justice Program, The Leadership Conference, at [email protected] or (202) 263-2894.

[vii] See Tracy Kyckelhahn, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Justice Expenditure and Employment Extracts, 2012,Preliminary Tbl. 1 (2015), https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5239 (showing FY 2012 state and federal corrections expenditure was $80,791,046,000).

[xi] A “safety valve” is an exception to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. A safety valve allows a judge to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum term if certain conditions are met. Safety valves can be broad or narrow, applying to many or few crimes (e.g., drug crimes only) or types of offenders (e.g., nonviolent offenders). See 18 U.S.C. 3553(f) (2010)

[xii] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

[xiii] Although the ACLU supported the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, we would ultimate support a change in law that would treat crack and powder cocaine equally; 1 to 1 ratio.

[xiv] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

[xviii] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

On Thursday September 8, 2022, federal prisoners across the country eagerly awaited the announcement of the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ (BOP) auto-calculation of First Step Act credits. For many Low and Minimum security inmates, the announcement landed with a thud.

The First Step Act (FSA) was one of the most sweeping pieces of criminal justice reform in decades. Signed into law by President Donald Trump in December 2018, the law allowed eligible inmates, those with an unlikely chance of recidivism and low or minimum security, to earn credits toward an earlier release from prison. Those credits were to be earned by prisoners participating in certain needs-based educational programs and actively participating in productive activities, like a prison job. For every 30 days of successful participation, the prisoner could earn up to 15 days off their sentence up to a maximum of 12 months (365 days). That is what the law states, but the BOP added a new wrinkle stating that those with short sentences, who are also more likely to be minimum or low security, will get no benefit of an earlier release.

“Eligible inmates will continue to earn FTC [Federal Time Credits] toward early release until they have accumulate 365 days OR are 18 months from their release date, whichever happens first [emphasis added by BOP]. At this point, the release date becomes fixed, and all additional FTCs are applied toward RRC/HC [Residential Reentry Centers / Home Confinement] placement.”

The BOP is known for narrowly interpreting policies that could lead to prisoners being taken out of their correctional institution custody. In fact, the BOP’s initial interpretation how prisoner’s earned FSA credits was so cumbersome and limiting that almost nobody would have realized a reduction in their sentence. Congressman Hakeem Jeffries (D–NY) comment in on the BOP’s early interpretation of the type of participation needed to earn credits said that is, “...does not appear to be a good faith attempt to honor congressional intent.” It is clear that Congress wanted fewer minimum security prisoners in prison.

With this more restrictive condition, BOP is even going against the Department of Justice’s intent of FSA which was to “transfer eligible inmates who satisfy the criteria in 3624(g) [awarding of FSA credits] to supervised release to the extent practicable, rather than prerelease custody [halfway house and home confinement].” The internal memorandum posted went on to state prisoners with “immigration issues” would not be eligible. One person who retired from the BOP said of the memorandum, “BOP is creating their own language and leaving the discretion in the hands of case managers to interpret who is eligible and who is not. They have completely disrespected the intent and FSA law states.”

Solutions: Shift funding from local or state public safety budgets into a local grant program to support community-led safety strategies in communities most impacted by mass incarceration, over-policing, and crime. States can use Colorado’s “Community Reinvestment” model. In fiscal year 2021-22 alone, four Community Reinvestment Initiatives will provide $12.8 million to community-based services in reentry, harm reduction, crime prevention, and crime survivors.

More information: See details about the CAHOOTS program. For a review of other strategies ranging from police-based responses to community-based responses, see the Vera Institute of Justice’s Behavioral Health Crisis Alternatives, the Brookings Institute’s Innovative solutions to address the mental health crisis, and The Council of State Governments’ Expanding First Response: A Toolkit for Community Responder Programs.

Reclassify criminal offenses and turn misdemeanor charges that don’t threaten public safety into non-jailable infractions, or decriminalize them entirely.

More information:For information on the youth justice reforms discussed, see The National Conference of State Legislatures Juvenile Age of Jurisdiction and Transfer to Adult Court Laws; the recently-closed Campaign for Youth Justice resources summarizing legislative reforms to Raise the Age, limit youth transfers, and remove youth from adult jails (available here and here); Youth First Initiative’s No Kids in Prison campaign; and The Vera Institute of Justice’s Status Offense Toolkit.

Legislation: Tennessee SB 0985/ HB 1449 (2019) and Massachusetts S 2371 (2018) permit or require primary caregiver status and available alternatives to incarceration to be considered for certain defendants prior to sentencing. New Jersey A 3979 (2018) requires incarcerated parents be placed as close to their minor child’s place of residence as possible, allows contact visits, prohibits restrictions on the number of minor children allowed to visit an incarcerated parent, and also requires visitation be available at least 6 days a week.

More information:See Families for Justice as Healing, Free Hearts, Operation Restoration, and Human Impact Partners’ Keeping Kids and Parents Together: A Healthier Approach to Sentencing in MA, TN, LA and the Illinois Task Force on Children of Incarcerated Parents’ Final Report and Recommendations.

Legislation: Illinois Pretrial Fairness Act, HB 3653 (2019), passed in 2021, abolishes money bail, limits pretrial detention, regulates the use of risk assessment tools in pretrial decisions, and requires reconsideration of pretrial conditions or detention at each court date. When this legislation takes effect in 2023, roughly 80% of people arrested in Cook County (Chicago) will be ineligible for pretrial detention.

More information: See The Bail Project’s After Cash Bail, the Pretrial Justice Institute’s website, the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School’s Moving Beyond Money, and Critical Resistance & Community Justice Exchange’s On the Road to Freedom. For information on how the bail industry — which often actively opposes efforts to reform the money bail system — profits off the current system, see our report All profit, no risk: How the bail industry exploits the legal system.

Solutions: States should pass legislation establishing moratoriums on jail and prison construction. Moratoriums on building new, or expanding existing, facilities allow reforms to reduce incarceration to be prioritized over proposals that would worsen our nation’s mass incarceration epidemic. Moratoriums also allow for the impact of reforms enacted to be fully realized and push states to identify effective alternatives to incarceration.

Problem: With approximately 80 percent of criminal defendants unable afford to an attorney, public defenders play an essential role in the fight against mass incarceration. Public defenders fight to keep low-income individuals from entering the revolving door of criminal legal system involvement, reduce excessive sentences, and prevent wrongful convictions. When people are provided with a public defender earlier, such as prior to their first appearance, they typically spend less time in custody. However, public defense systems are not adequately resourced; rather, prosecutors and courts hold a disproportionate amount of resources. The U.S. Constitution guarantees legal counsel to individuals who are charged with a crime, but many states delegate this constitutional obligation to local governments, and then completely fail to hold local governments accountable when defendants are not provided competent defense counsel.

Problem: Nationally, one of every six people in state prisons has been incarcerated for a decade or more. While many states have taken laudable steps to reduce the number of people serving time for low-level offenses, little has been done to bring relief to people needlessly serving decades in prison.

Solutions: State legislative strategies include: enacting presumptive parole, second-look sentencing, and other common-sense reforms, such as expanding “good time” credit policies. All of these changes should be made retroactive, and should not categorically exclude any groups based on offense type, sentence length, age, or any other factor.

Legislation: Federally, S 2146 (2019), the Second Look Act of 2019, proposed to allow people to petition a federal court for a sentence reduction after serving at least 10 years. California AB 2942 (2018) removed the Parole Board’s exclusive authority to revisit excessive sentences and established a process for people serving a sentence of 15 years-to-life to ask the district attorney to make a recommendation to the court for a new sentence after completing half of their sentence or 15 years, whichever comes first. California AB 1245 (2021) proposed to amend this process by allowing a person who has served at least 15 years of their sentence to directly petition the court for resentencing. The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers has created model legislation that would allow a lengthy sentence to be revisited after 10 years.

Problem: Automatic sentencing structures have fueled the country’s skyrocketing incarceration rates. For example, mandatory minimum sentences, which by the 1980s had been enacted in all 50 states, reallocate power from judges to prosecutors and force defendants into plea bargains, exacerbate racial disparities in the criminal legal system, and prevent judges from taking into account the circumstances surrounding a criminal charge. In addition, “sentencing enhancements,” like those enhanced penalties that are automatically applied in most states when drug crimes are committed within a certain distance of schools, have been shown to exacerbate racial disparities in the criminal legal system. Both mandatory minimums and sentencing enhancements harm individuals and undermine our communities and national well-being, all without significant increases to public safety.

Solutions: The best course is to repeal automatic sentencing structures so that judges can craft sentences to fit the unique circumstances of each crime and individual. Where that option is not possible, states should: adopt sentencing “safety valve” laws, which give judges the ability to deviate from the mandatory minimum under specified circumstances; make enhancement penalties subject to judicial discretion, rather than mandatory; and reduce the size of sentencing enhancement zones.

Legislation: Several examples of state and federal statutes are included in Families Against Mandatory Minimums’ (FAMM) Turning Off the Spigot. The American Legislative Exchange Council has produced model legislation, the Justice Safety Valve Act.

Problem: The release of individuals who have been granted parole is often delayed for months because the parole board requires them to complete a class or program (often a drug or alcohol treatment program) that is not readily available before they can go home. As of 2015, at least 40 states used institutional program participation as a factor in parole determinations. In some states — notably Tennessee and Texas — thousands of people whom the parole board deemed “safe” to return to the community remain incarcerated simply because the state has imposed this bureaucratic hurdle.

Solutions: States should increase the dollar amount of a theft to qualify for felony punishment, and require that the threshold be adjusted regularly to account for inflation. This change should also be made retroactive for all people currently in prison, on parole, or on probation for felony theft.

Problem: Probation and parole are supposed to provide alternatives to incarceration. However, the conditions of probation and parole are often unrelated to the individual’s crime of conviction or their specific needs, and instead set them up to fail. For example, restrictions on associating with others and requirements to notify probation or parole officers before a change in address or employment have little to do with either public safety or “rehabilitation.” Additionally, some states allow community supervision to be revoked when a person is “alleged” to have violated — or believed to be “about to” violate — these or other terms of their supervision. Adding to the problem are excessively long supervision sentences, which spread resources thin and put defendants at risk of lengthy incarceration for subsequent minor offenses or violations of supervision rules. Because probation is billed as an alternative to incarceration and is often imposed through plea bargains, the lengths of probation sentences do not receive as much scrutiny as they should.

Solutions: States should limit incarceration as a response to supervision violations to when the violation has resulted in a new criminal conviction and poses a direct threat to public safety. If incarceration is used to respond to technical violations, the length of time served should be limited and proportionate to the harm caused by the non-criminal rule violation.

More information: Challenging E-Carceration, provides details about the encroachment of electronic monitoring into community supervision, and Cages Without Bars provides details about electronic monitoring practices across a number of U.S. jurisdictions and recommendations for reform. Fact sheets, case studies, and guidelines for respecting the rights of people on electronic monitors are available from the Center for Media Justice.

Solutions: Stop suspending, revoking, and prohibiting the renewal of driver’s licenses for nonpayment of fines and fees. Since 2017, fifteen states (Calif., Colo., Hawaii, Idaho, Ill., Ky., Minn., Miss., Mont., Nev., Ore., Utah, Va., W.Va., and Wyo.) and the District of Columbia have eliminated all of these practices.

More information: See our briefing with national data and state-specific data for 15 states (Colo., Idaho, Ill., La., Maine, Mass., Mich., Miss., Mont., N.M., N.D., Ohio, Okla., S.C., and Wash.) that charge monthly fees even though half (or more) of their probation populations earn less than $20,000 per year. States with privatized misdemeanor probation systems will find helpful the six recommendations on pages 7-10 of the Human Rights Watch report Set up to Fail: The Impact of Offender-Funded Private Probation on the Poor.

Problem: Calls home from prisons and jails cost too much because the prison and jail telephone industry offers correctional facilities hefty kickbacks in exchange for exclusive contracts. While most state prison phone systems have lowered their rates, and the Federal Communications Commission has capped the interstate calling rate for small jails at 21c per minute, many jails are charging higher prices for in-state calls to landlines.

Legislation and regulations: Legislation like Connecticut’s S.B. 972 (2021) ensured that the state — not incarcerated people — pay for the cost of calls. Short of that, the best model is New York Corrections Law S 623 which requires that contracts be negotiated on the basis of the lowest possible cost to consumers and bars the state from receiving any portion of the revenue. (While this law only applied to contracts with state prisons, an ideal solution would also include local jail contracts.) States can also increase the authority of public utilities commissions to regulate the industry (as Colorado did) and California Public Utilities Commission has produced the strongest and most up-to-date state regulations of the industry.

Solutions: States have the power to decisively end this pernicious practice by prohibiting facilities from using release cards that charge fees, and requiring fee-free alternative payment methods.

Problem: Despite a growing body of evidence that medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is effective at treating opioid use disorders, most prisons are refusing to offer those treatments to incarcerated people, exacerbating the overdose and recidivism rate among people released from custody. In fact, studies have stated that drug overdose is the leading cause of death after release from prison, and the risk of death is significantly higher for women.

Legislation and model program: New York SB 1795 (2021) establishes MAT for people incarcerated in state correctional facilities and local jails. In addition, Rhode Island launched a successful program to provide MAT to some of the people incarcerated in their facilities. The early results are very encouraging: In the first year, Rhode Island reported a 60.5% reduction in opioid-related mortality among recently incarcerated people.

Solutions: Change state laws and/or state constitutions to remove disenfranchising provisions. Additionally, governors should immediately restore voting rights to disenfranchised people via executive action when they have the power to do so.

Legislation: D.C. B 23-0324 (2019) ended the practice of felony disenfranchisement for Washington D.C. residents; Hawai’i SB 1503/HB 1506 (2019) would have allowed people who were Hawai’i residents prior to incarceration to vote absentee in Hawai’i elections; New Jersey A 3456/S 2100 (2018) would have ended the practice of denying New Jersey residents incarcerated for a felony conviction of their right to vote.

Problem: Many people who are detained pretrial or jailed on misdemeanor convictions maintain their right to vote, but many eligible, incarcerated people are unaware that they can vote from jail. In addition, state laws and practices can make it impossible for eligible voters who are incarcerated to exercise their right to vote, by limiting access to absentee ballots, when requests for ballots can be submitted, how requests for ballots and ballots themselves must be submitted, and how errors on an absentee ballot envelope can be fixed.

Problem: The Census Bureau’s practice of tabulating incarcerated people at correctional facility locations (rather than at their home addresses) leads state and local governments to draw skewed electoral districts that grant undue political clout to people who live near large prisons and dilute the representation of people everywhere else.

Solutions: States can pass legislation to count incarcerated people at home for redistricting purposes, as Calif., Colo., Conn., Del., Ill., Md., Nev., N.J., N.Y, Va., and Wash. have done. Ideally, the Census Bureau would implement a national solution by tabulating incarcerated people at home in the 2030 Census, but states must be prepared to fix their own redistricting data should the Census fail to act. Taking action now ensures that your state will have the data it needs to end prison gerrymandering in the 2030 redistricting cycle.

Problem: In courthouses throughout the country, defendants are routinely denied the promise of a “jury of their peers,” thanks to a lack of racial diversity in jury boxes. One major reason for this lack of diversity is the constellation of laws prohibiting people convicted (or sometimes simply accused) of crimes from serving on juries. These laws bar more than twenty million people from jury service, reduce jury diversity by disproportionately excluding Black and Latinx people, and actually cause juries to deliberate less effectively. Such exclusionary practices often ban people from jury service forever.

Problem: The impacts of incarceration extend far beyond the time that a person is released from prison or jail. A conviction history can act as a barrier to employment, education, housing, public benefits, and much more. Additionally, the increasing use of background checks in recent years, as well as the ability to find information about a person’s conviction history from a simple internet search, allows for unchecked discrimination against people who were formerly incarcerated. The stigma of having a conviction history prevents individuals from being able to successfully support themselves, impacts families whose loved ones were incarcerated, and can result in higher recidivism rates.

Ensure that people have access to health care benefits prior to release. Screen and help people enroll in Medicaid benefits upon incarceration and prior to release; if a person’s Medicaid benefits were suspended upon incarceration, ensure that they are active prior to release; and ensure people have their medical cards upon release.

Legislation:Rhode Island S 2694 (2022) proposed to: maintain Medicaid enrollment for the first 30 days of a person’s incarceration; require Medicaid eligibility be determined, and eligible individuals enrolled, upon incarceration; require reinstatement of suspended health benefits and the delivery of medical assistance identify cards prior to release from incarceration.

Problem: Four states have failed to repeal another outdated relic from the war on drugs — automatic driver’s license suspensions for all drug offenses, including those unrelated to driving. Our analysis shows that there are over 49,000 licenses suspended every year for non-driving drug convictions. These suspensions disproportionately impact low-income communities and waste government resources and time.

A criminal justice reform effort known as the First Step Act is just one step — a signature from President Donald Trump — away from becoming law and changing the lives of an estimated 30% of the federal prison population over the next decade.

Since the First Step Act was introduced earlier this year, it has earned the support of both Democrats and Republicans, though some Democrats say the bill doesn’t do enough in regards to sentencing laws that disproportionately affect minorities. The legislation has also gotten support from groups like the American Civil Liberties Union and the Fraternal Order of Police.

The bill will give federal judges discretion to skirt mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines for more people, according to the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Currently, judges use what is known as a “safety valve” for nonviolent drug offenders with no prior criminal background. But the bill will allow it to expand to include people with limited criminal histories. An additional 2,000 people each year would be eligible for exemption from mandatory sentences if the bill passes, according to estimates by the Congressional Budget Office.

“It seems like a minimum step, but getting five years of your life, being able to know you have an opportunity, we believe that changes a lot within the prison system,” Michael Deegan-Mccree, policy associate at Cut 50, a prison reform advocacy group that worked to get the First Step Act bill passed says. “It’s also something members on both sides of the aisle have said they are very interested in coming back to and possibly even lessening mandatory minimums even more, and so thats something were really happy about.”

The First Step Act would allow for the increase the amount of “good time credits,” which reduce prison time for good behavior, inmates can earn. Prisoners can earn up to 54 “good time credits” a year, which can reduce sentences by months depending on time served. “Good time” credits can be taken away from prisoners if they have an infraction while inside a facility.

Deegan-Mccree says the “good time credit” amendment in the bill was added to adjust the amount of credit prisoners get. “What happened is that this was not calculated correctly and people were actually getting 47 days of good time credit,” he says. “So what this bill does is that it fixes that and gives people the appropriate amount of time that people were supposed to get in the first place.”

This will retroactively apply to everyone in federal prison who has earned credit for good behavior, allowing some men and women to leave prison soon after the bill passes, according to firststep.org.

In addition to the fixed “good time credit,” inmates will also have the opportunity to earn credits through the First Step Act. Inmates earn “earned time credits” by taking part in programs once they are brought in to a facility. Inmates are evaluated and put into a “risk category” based on a previous infraction, usually the crime that they were imprisoned for. An independent review committee along with the Attorney General’s office and the Bureau of Prisons that looks at persons needs.

Inmates will then have the opportunity to exchange those earned credits after two years of non-infraction and if they are down to low or minimal level risk, they can trade in that time and serve the rest of their sentence either in home confinement or a halfway house.

The bill will also adds incentives for inmates to participate in programs, including “earned time credits.” The bill would allow for 10 days in prerelease custody for every 30 days of successful participation, with no cap on the prerelease credit that can be earned, according to estimates by the Marshall Act.

The First Step Act will also ban the shackling of pregnant women, and extending that to three months after her pregnancy. Deegan-Mccree says that Cut 50 has worked on a statewide campaign called “dignity for incarcerated women” and on of its primary focuses has been to help bring about such a ban.

“What we’ve done in certain states is try to ban that horrific practice of shackling a woman to a bed while she is giving birth to her baby,” he says. “Studies show that trauma goes straight to the baby. So we tried to pass stand alone bill that dealt with this portion but we thought the First Step Act is all about prison reform and that it was important that this language made it into the bill as well.”

“It was very important that people saw that this was happening, there were many people who didn’t know this practice existed and to bring that to light through policy and say this is not okay to treat human beings like that is extremely important to us.”

“The dignity is stripped from women,” he says. “There isn’t anything more demeaning. It is extremely important not just for women but for men as well to understand what women have to go through when they���re incarcerated. Today in our mass incarceration age, women are the highest growing rate of people getting locked up. This has a huge impact on whole communities because women are usually primary caretakers of community. People need to understand that this affects all of us.”

On December 21, 2018, President Donald Trump signed into law the 56-page First Step Act (S. 756), a bill that will usher in an array of reforms within the federal criminal justice system. The bill went to the president’s desk just days after passing the Senate on an 87-12 vote.

Seen by its proponents as a major policy victory, others have cautioned that – while a positive step in the right direction – the legislation still leaves much to be desired. From the most sinister lens, critics point out it will likely benefit the private prison industry while excluding certain prisoners from some of its beneficial provisions.

The First Step Act has 36 distinct sections which address many aspects of federal sentencing and prison-related policies. They range from placing prisoners in facilities closer to their families to sentencing reform and de-escalation training for guards, plus creating a risk and needs assessment system. The bill also calls for studies on medication-assisted opioid addiction treatment for prisoners, and an expansion and accompanying audit of Federal Prison Industries (UNICOR), the Bureau of Prisons’ industry work program.

“This legislation is what it says it is: a first step; and while it is an important first step, it is not comprehensive criminal justice reform,” the Caucus stated in a press release.

“This victory truly belongs to the thousands of people who, like me, have been personally impacted by incarceration and have dedicated their lives to improving the system,” said Jessica Jackson-Sloan, director and cofounder of #cut50.

While the First Step Act reduces mandatory minimum sentences for certain serious drug-related crimes, including “three strike” drug offenders, such reductions are not retroactive and thus do not apply to prisoners currently serving harsh mandatory minimums. Going forward, 20-year mandatory sentences imposed on repeat drug offenders will be changed to 15 years, while life sentences imposed on three-strike drug offenders will be reduced to 25 years.

The bill does make retroactive the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act, which addresses the crack vs. powder cocaine sentencing disparity. Under that law, the disparity in sentences imposed for crack vs. powder cocaine charges was reduced from 100-to-one to 18-to-one. [See: PLN, Sept. 2010, p.26]. That change will now be applied retroactively to thousands of prisoners, resulting in shorter sentences in many cases. The process is not automatic, though; prisoners must file a motion or the BOP, a federal prosecutor or federal court must take action to seek a sentence reduction.

Additionally, the federal safety valve provision, which provides an exception to mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders with little or no criminal history, was broadened in the First Step Act – though not made retroactive.

The bill also clarifies the good time credits that federal prisoners can earn, specifying that such credits shall be “up to 54 days for each year of the prisoner’s sentence imposed by the court.” Previously, the BOP limited good time to 47 days per year. This change will be retroactive for all BOP prisoners.

As part of the risk and needs assessment system created by the First Step Act, federal prisoners will be assigned to evidence-based recidivism reduction programs, with incentives for participation that include additional phone, video visit and in-person visitation privileges, and transfer to a facility closer to a prisoner’s home. Other potential incentives include increased commissary spending limits, “extended opportunities to access the [BOP’s secure] email system” and moves to preferred housing units.

One criticism of risk-assessment systems, which are typically based on algorithms that use personal data to calculate risk scores, is that they are subject to racial bias. Whether that will be a factor in the BOP’s risk-assessment system remains to be seen.

The First Step Act also contains several sections that deal with reentry, which were supported by private prison companies such as GEO Group and CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America). Those companies, which own numerous halfway houses and reentry centers that contract with government agencies, explained their support for the legislation in terms of helping prisoners get back on their feet upon their release.

“GEO’s political and governmental relations activities focus on promoting the use of public-private partnerships in the delivery of correctional services including evidence-based rehabilitation programs, both in-custody and post-release, aimed at reducing recidivism and helping the men and women in our care successfully reintegrate into their communities,” the company said in one of its federal lobbying disclosure forms.

For its part, CoreCivic – which owns dozens of community corrections facilities – also expressed support for the First Step Act, including in a December 19, 2018 press statement attributed to President and CEO Damon Hininger.

That national network of reentry centers was built to generate profit, of course, and both CoreCivic and GEO stand to benefit from the funding included in the First Step Act. Previously, both companies successfully opposed a shareholder resolution that would have required them to spend just five percent of their net profit on reentry and rehabilitative programs. [See: PLN, Feb. 2015, p.48].

Prison Legal News managing editor Alex Friedmann told The Intercept that “business as usual” for the private prison industry will still reign supreme under the First Step Act.

The topic of reentry appears in four sections of the bill. Management and Training Corporation (MTC), a competitor to GEO Group and CoreCivic, also came out in support of the First Step Act. MTC operates community corrections and reentry facilities too, and thus stands to benefit from the legislation and the $75 million it authorizes each year from 2019 through 2023 to fund reentry and rehabilitative programs for federal prisoners.

Another provision of the bill centers around solitary confinement of juvenile offenders. The First Step Act specifies that solitary “room confinement” can be used as a form of punishment, but only as a “temporary response to a covered juvenile’s behavior that poses a serious and immediate risk of physical harm to any individual, including the covered juvenile.”

In the context of the opioid epidemic, the First Step Act dictates that the BOP produce a report – to be submitted to the Committees on the Judiciary and Committees on Appropriations in both houses of Congress – which examines medication-assisted treatment and if it is a viable option for federal prisoners who have opioid and heroin addictions.

“In preparing the report, the [Bureau of Prisons] shall consider medication-assisted treatment as a strategy to assist in treatment where appropriate and not as a replacement for holistic and other drug-free approaches,” the bill explains. “The report shall include a description of plans to expand access to evidence-based treatment for heroin and opioid abuse for prisoners, including access to medication-assisted treatment in appropriate cases. Following submission, the [BOP] shall take steps to implement these plans.”

Within 120 days, the bill calls for a similar course of action by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. It requires the “Director of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts [to] submit to the Committees on the Judiciary and the Committees on Appropriations of the Senate and of the House of Representatives a report assessing the availability of and capacity for the provision of medication-assisted treatment for opioid and heroin abuse by treatment service providers serving prisoners who are serving a term of supervised release, and including a description of plans to expand access to medication-assisted treatment for heroin and opioid abuse whenever appropriate among prisoners under supervised release.”

One part of the First Step Act that largely flew under the radar expands the use of prison labor. Buried on page 49 of the bill is a section that could greatly expand federal prison industry programs and the market for products produced using prisoner labor.

Titled “Expanding Inmate Employment Through Federal Prison Industries,” the section allows for more vendors to purchase items manufactured by UNICOR, while also requiring the agency to be audited by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) within 90 days after the bill goes into effect.

The First Step Act allows products produced by UNICOR to be sold to “public entities for use in penal or correctional institutions,” “public entities for use in disaster relief or emergency response” and “the government of the District of Columbia.” Further, non-profit organizations can now purchase items directly from UNICOR.

“First Step would expand inmate employment through federal prison industries. These private companies employ incarcerated people in federal prisons and pay wages far below the federal minimum wage,” the organization wrote. “We are concerned about the expansion of prison industries because of the exploitative nature of these jobs and believe if these programs exist and are to be expanded, they should pay a fair wage.”

Pursuant to the First Step Act, the GAO will perform an “evaluation of the scope and size of the additional markets made available to Federal Prison Industries under this section [of the bill] and the total market value that would be opened up to Federal Prison Industries for competition with private sector providers of products and services.”

The GAO will also examine prisoner wages, doing so by “taking into account inmate productivity” while also evaluating whether UNICOR programs have a positive impact on recidivism rates once incarcerated workers are released.

The First Step Act includes a provision that bans the shackling of pregnant prisoners, “beginning on the date on which pregnancy is confirmed by a healthcare professional, and ending at the conclusion of postpartum recovery,” unless a prisoner poses “an immediate and serious threat of harm” to herself or others. All uses of restraints on pregnant prisoners must be reported.

With respect to where prisoners are housed, and in a nod to the importance of family support during incarceration, the First Step Act states the BOP “shall designate the place of the prisoner’s imprisonment, and shall, subject to bed availability, the prisoner’s security designation, the prisoner’s programmatic needs, the prisoner’s mental and medical health needs, any request made by the prisoner related to faith-based needs, recommendations of the sentencing court, and other security concerns of the Bureau of Prisons, place the prisoner in a facility as close as practicable to the prisoner’s primary residence, and to the extent practicable, in a facility within 500 driving miles of that residence.”

The Correctional Officer Self-Protection Act, which was merged into the First Step Act, was drafted in response to the 2013 murder of BOP Lt. Osvaldo Albarati at the Metropolitan Detention Center, Guaynabo in Puerto Rico. Albarati was killed in a drive-by shooting after he finished his shift, reportedly in retribution for investigations he was conducting into cell phone smuggling at the facility.

Finally, among various other provisions – many of them technical in nature – the First Step Act reauthorizes the Second Chance Act, which provides funding for reentry programs and services, and includes improvements to the BOP’s compassionate release process – which has long been criticized. [See: PLN, Aug. 2018, p.58; Dec. 2014, p.50].

“It’s right there in the name: It’s called the First Step Act, acknowledging that it’s, well, a first step. The bill doesn’t end the war on drugs or mass incarceration. It won’t stop law enforcement from locking up nonviolent drug offenders. It doesn’t legalize marijuana. It doesn’t even end mandatory minimums or reduce prison sentences across the board, and it in fact only tweaks both,” Lopez wrote. “This isn’t to take away from the legislation or suggest that it wasn’t worth doing. Thousands of federal prison inmates will benefit from the bill. But it’s important to put the bill in a broader context – to not oversell its impact, and to acknowledge there’s still a lot more room to make America’s federal criminal justice system less punitive.”

It’s indeed a first step, one perhaps better described as a baby step. And it needs to be followed by a second step, third step and more – though the chances of additional criminal justice reform legislation being passed by Congress are exceedingly slim.

Sources: www.congress.gov, www.cnn.com, www.theintercept.com, www.bop.gov, www.prisonstudies.org, www.vox.com, www.unicor.gov, www.oversight.gov, www.wvnews.com, www.clasp.org, www.soprweb.senate.gov, www.opensecrets.org, www.mtctrains.com, www.c-span.org, www.cbc.house.gov, www.tampabay.com, www.lasentinel.net, www.theconversation.com, www.disclosures.house.gov, www.investors.geogroup.com, www.corecivic.com, www.theguardian.com, www.freedomworks.org, www.firststepact.org

The “safety valve” sentencing provision in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) allows a district court to sentence a defendant below the mandatory-minimum sentence for certain drug offenses if the defendant can show he or she doesn’t have all three conviction categories, together, that are listed in the statute, the Ninth Circuit held Friday in United States v. Lopez, No. 19-50305 (9th Cir. May 21, 2021).

The term “and” in the statute, 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)(1), means “and,” the court held. "Applying the tools of statutory construction, we hold that § 3553(f)(1)’s “and” is unambiguously conjunctive. Put another way, we hold that "and" means "and".” “A defendant must have all three before § 3553(f)(1) bars him or her from safety-valve relief,” referring to the three categories of prior convictions.

Up until 2018, anyone with more than one “criminal history point” under the Sentencing Guidelines was safety valve ineligble. Specifically, anyone who had been sentenced to more than 60 days in jail or had more than one conviction of any kind (including misdemeanors) was excluded.

As soon as mankind was able to boil water to create steam, the necessity of the safety device became evident. As long as 2000 years ago, the Chinese were using cauldrons with hinged lids to allow (relatively) safer production of steam. At the beginning of the 14th century, chemists used conical plugs and later, compressed springs to act as safety devices on pressurised vessels.

Early in the 19th century, boiler explosions on ships and locomotives frequently resulted from faulty safety devices, which led to the development of the first safety relief valves.

In 1848, Charles Retchie invented the accumulation chamber, which increases the compression surface within the safety valve allowing it to open rapidly within a narrow overpressure margin.

Today, most steam users are compelled by local health and safety regulations to ensure that their plant and processes incorporate safety devices and precautions, which ensure that dangerous conditions are prevented.

The principle type of device used to prevent overpressure in plant is the safety or safety relief valve. The safety valve operates by releasing a volume of fluid from within the plant when a predetermined maximum pressure is reached, thereby reducing the excess pressure in a safe manner. As the safety valve may be the only remaining device to prevent catastrophic failure under overpressure conditions, it is important that any such device is capable of operating at all times and under all possible conditions.

Safety valves should be installed wherever the maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP) of a system or pressure-containing vessel is likely to be exceeded. In steam systems, safety valves are typically used for boiler overpressure protection and other applications such as downstream of pressure reducing controls. Although their primary role is for safety, safety valves are also used in process operations to prevent product damage due to excess pressure. Pressure excess can be generated in a number of different situations, including:

The terms ‘safety valve’ and ‘safety relief valve’ are generic terms to describe many varieties of pressure relief devices that are designed to prevent excessive internal fluid pressure build-up. A wide range of different valves is available for many different applications and performance criteria.

In most national standards, specific definitions are given for the terms associated with safety and safety relief valves. There are several notable differences between the terminology used in the USA and Europe. One of the most important differences is that a valve referred to as a ‘safety valve’ in Europe is referred to as a ‘safety relief v

8613371530291

8613371530291