first step act safety valve provision brands

The Federal Safety Valve law permits a sentence in a drug conviction to go below the mandatory drug crime minimums for certain individuals that have a limited prior criminal history. This is a great benefit for those who want a second chance at life without sitting around incarcerated for many years. Prior to the First Step Act, if the defendant had more than one criminal history point, then they were ineligible for safety valve. The First Step Act changed this, now allowing for up to four prior criminal history points in certain circumstances.

The First Step Act now gives safety valve eligibility if: (1) the defendant does not have more than four prior criminal history points, excluding any points incurred from one point offenses; (2) a prior three point offense; and (3) a prior two point violent offense. This change drastically increased the amount of people who can minimize their mandatory sentence liability.

Understanding how safety valve works in light of the First Step Act is extremely important in how to incorporate these new laws into your case strategy. For example, given the increase in eligible defendants, it might be wise to do a plea if you have a favorable judge who will likely sentence to lesser time. Knowing these minute issues is very important and talking to a lawyer who is an experienced federal criminal defense attorney in southeast Michigan is what you should do. We are experienced federal criminal defense attorneys and would love to help you out. Contact us today.

In December 2018, President Trump signed into law the First Step Act, which mostly involves prison reform, but also includes some sentencing reform provisions.

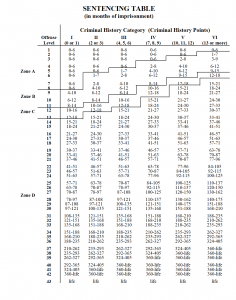

The key provision of the First Step Act that relates to sentencing reform concerns the “safety valve” provision of the federal drug trafficking laws. The safety valve allows a court to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum sentence for the crime, and to reduce the person’s offense level under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines by two points.

The First Step Act increases the availability of the safety valve by making it easier to meet the first requirement—little prior criminal history. Before the First Step Act, a person could have no more than one criminal history point. This generally means no more than one prior conviction in the last ten years for which the person received either probation or less than 60 days of prison time.

Section 402 of the First Step Act changes this. Now, a person is eligible for the safety valve if, in addition to meeting requirements 2-5 above, the defendant does not have:

This news has been published for the above source. Kiss PR Brand Story Press Release News Desk was not involved in the creation of this content. For any service, please contact https://story.kisspr.com.

On behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, we write to urge you to vote YES on S. 756, the FIRST STEP Act. This legislation is a next step towards desperately needed federal criminal justice reform, but for all its benefits, much more needs to be done. The inclusion of concrete sentencing reforms in the new and improved Senate version of the FIRST STEP Act is a modest improvement, but many people will be left in prison to serve long draconian sentences because some provisions of the legislation are not retroactive. The revised FIRST STEP Act, however, is not without problems. The bill continues to exclude individuals from benefiting from some provisions based solely on their prior offenses, namely citizenship and immigration status, as well as certain prior drug convictions and their “risk score” as determined by a discriminatory risk assessment system. While these concerns remain a priority for our organizations and we will advocate for improvements in the future, ultimately the improvements to the federal sentencing scheme will have a net positive impact on the lives of some of the people harmed by our broken justice system and we urge you to vote YES on S. 756. The ACLU and The Leadership Conference will include your votes on our updated voting scorecards for the 115th Congress.

While the dollar amounts are astounding, the toll that our U.S. criminal justice policies have taken on black and brown communities across the nation goes far beyond the enormous amount of money that is spent. This country’s extraordinary incarceration rates impose much greater costs than simply the fiscal expenditures necessary to incarcerate over 20 percent of the world’s prisoners. The true costs of this country’s addiction to incarceration must be measured in human lives and particularly the generations of young black and Latino men who serve long prison sentences and are lost to their families and communities. The Senate version of the FIRST STEP Act makes some modest improvements to the current federal system.

I. Sentencing Reform Changes to House-passed FIRST STEP Act–Sentencing reform is the key to slowing down the flow of people going into our prisons. This makes sentencing reform pivotal to addressing mass incarceration, prison overcrowding, and the exorbitant costs of incarceration. As a result of our coalition’s advocacy, the new FIRST STEP Act added some important sentencing reform provisions from SRCA, which will aid us in tackling these issues on the federal level.[x] These important changes in federal law will result in fewer people being subjected to harsh mandatory minimums.

Expands the Existing Safety Valve. The revised bill expands eligibility for the existing safety valve under 18 U.S.C 3553(f)[xi] from one to four criminal history points if a person does not have prior 2-point convictions for crimes of violence or drug trafficking offenses and prior 3-point convictions. Under the expanded safety valve, judges will have discretion to make a person eligible for the safety valve in cases where the seriousness of his or her criminal history is over-represented, or it is unlikely he or she would commit other crimes. This crucial expansion of the safety valve will reduce sentences for an estimated 2,100 people per year.[xii]

Retroactive Application of Fair Sentencing Act (FSA). The new version of FIRST STEP Act would retroactively apply the statutory changes of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (FSA), which reduced the disparity in sentence lengths between crack and powder cocaine. This change in the law will allow people who were sentenced under the harsh and discriminatory 100 to 1 crack to powder cocaine ratio to be resentenced under the 2010 law.[xiii] This long overdue improvement would allow over 2,600 people the chance to be resentenced.[xiv]

Reforms the Unfair Two-Strikes and Three-Strikes Laws. The new version of FIRST STEP would reduce the impact of certain mandatory minimums. It would reduce the mandatory life sentence for a third drug felony to a mandatory minimum sentence of 25 years and reduce the 20-year mandatory minimum for a second drug felony to 15 years.

Eliminates 924(c) “stacking”.The revised bill would also amend 18 U.S.C. 924(c), which currently allows “stacking,” or consecutive sentences for gun charges stemming from a single incident committed during a drug crime or a crime of violence. The legislation would require a prior gun conviction to be final before a person could be subject to an enhanced sentence for possession of a firearm. This provision in federal law has resulted in very long and unjust sentences.[xv]

II. Prison Reform Changes to House-passed FIRST STEP Act, H.R. 3356–The revised bill also made some strides in improving some of the problematic prison reform provisions. The new bill strengthened oversight over the new risk assessment system, limited the discretion of the attorney general, and increased funding for prison programming, among other things. The bill now does the following:

Permits Early Community Release and Loosens Restrictions on Home Confinement.The House-passed FIRST STEP Act limited the use of earned credits to time in prerelease custody (halfway house or home confinement). The revised bill would expand the use of earned credits to supervised release in the community. The bill also would permit individuals in home confinement to participate in family-related activities that facilitate the prisoner’s successful reentry.

Reauthorizes Second Chance Act. The revised bill reauthorizes the Second Chance Act, which provides federal funding for drug treatment, vocational training, and other reentry and recidivism programming.

While these revisions to the bill were critical to garnering our support, we must acknowledge that some of the more concerning aspects of the House-passed version of the FIRST STEP Act remain.

III. Outstanding Concerns Regarding the FIRST STEP Act–The bill continues to exclude too many people from earning time credits, including those convicted of immigration-related offenses. It does not retroactively apply its sentencing reform provisions to people convicted of anything other than crack convictions, continues to allow for-profit companies to benefit off of incarceration, fails to address parole for juveniles serving life sentences in federal prison, and expands electronic monitoring.

Fails to Include Retroactivity for Enhanced Mandatory Minimum Sentences for Prior Drug Offenses &. 924(c) “stacking.”The bill does not include retroactivity for its sentencing reforms besides the long-awaited retroactivity for the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010. This minimizes the overall impact substantially. Retroactivity is a vital part of any meaningful sentencing reform. Not only does it ensure that the changes we make to our criminal justice system benefit the people most impacted by it, but it’s also one of the essential policy changes to reduce mass incarceration. The federal prison population has fallen by over 38,000[xvi] since 2013 thanks in large part to retroactive application of sentencing guidelines approved by the U.S. Sentencing Commission.[xvii] More than 3,000 people will be left in prison without retroactive application of the “three strikes” law and the change to the 924 (c) provisions in the FIRST STEP Act.[xviii]

Excludes Too Many Federal Prisoners from New Earned Time Credits. The bill continues to exclude many federal prisoners from earning time credits and excludes many federal prisoners from being able to “cash in” the credits they earn. The long list of exclusions in the bill sweep in, for example, those convicted of certain immigration offenses and drug offenses.[xix] Because immigration and drug offenses account for 53.3 percent of the total federal prison population, many people could be excluded from utilizing the time credits they earned after completing programming.[xx] The continued exclusion of immigrants from the many benefits of the bill simply based on immigration status is deeply troubling. The Senate version of FIRST STEP maintains a categorical exclusion of people convicted of certain immigration offenses from earning time credits under the bill. The new version of the bill also bars individuals from using the time credits they have earned if they have a final order of removal. More than 12,000 people are currently in federal prison for immigration offenses and are disproportionately people of color.[xxi] Thus, a very large number of people in federal prison would not reap the benefits proposed in this bill and a disproportionate number of those excluded would be people of color. Denying early-release credits to certain people also reduces their incentive to complete the rehabilitative programs and contradicts the goal of increasing public safety. Any reforms enacted by Congress should impact a significant number of people in federal prison and reduce racial disparities or they will have little effect on the fiscal and human costs of incarceration.

Allows Private Prison Companies to Profit. The bill also maintains concerning provisions that could privatize government functions and allow the Attorney General excessive discretion. FIRST STEP provides that in order to expand programming, BOP shall enter into partnerships with private organizations and companies under policies developed by the Attorney General, “subject to appropriations.” This could result in the further privatization of what should be public functions and would allow private entities to unduly profit from incarceration.

Fails to Include Parole for Juveniles, Sealing and Expungement. Under SRCA, judges would have discretion to reduce juvenile life without parole sentences after 20 years. It would also permit some juveniles to seal or expunge non-violent convictions from their record. The FIRST STEP Act does not address these important bipartisan provisions.

Bringing fairness and dignity to our justice system is one of the most important civil and human rights issues of our time. The revised version of the FIRST STEP Act is a modest, but important move towards achieving some meaningful reform to the criminal legal system. While the bill continues to have its problems, and we will fight to address those in the future, it does include concrete sentencing reforms that would impact people’s lives. For these reasons, we urge you to vote YES on S. 756.

Ultimately, the First Step Act is not the end– it is just the next in a series of efforts over the past 10 years to achieve important federal criminal justice reform. Congress must take many more steps to undo the harms of the tough on crime policies of the 80’s and 90’s – to create a system that is just and equitable, significantly reduces the number of people unnecessarily entering the system, eliminates racial disparities, and creates opportunities for second chances.

If you have any additional questions, please feel free to contact Jesselyn McCurdy, Deputy Director, ACLU Washington Legislative Office, at [email protected] or (202) 675-2307 or Sakira Cook, Director, Justice Program, The Leadership Conference, at [email protected] or (202) 263-2894.

[vii] See Tracy Kyckelhahn, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Justice Expenditure and Employment Extracts, 2012,Preliminary Tbl. 1 (2015), https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5239 (showing FY 2012 state and federal corrections expenditure was $80,791,046,000).

[xi] A “safety valve” is an exception to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. A safety valve allows a judge to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum term if certain conditions are met. Safety valves can be broad or narrow, applying to many or few crimes (e.g., drug crimes only) or types of offenders (e.g., nonviolent offenders). See 18 U.S.C. 3553(f) (2010)

[xii] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

[xiii] Although the ACLU supported the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, we would ultimate support a change in law that would treat crack and powder cocaine equally; 1 to 1 ratio.

[xiv] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

[xviii] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

Congress changed all of that in the First Step Act. In expanding the number of people covered by the safety valve, Congress wrote that a defendant now must only show that he or she “does not have… (A) more than 4 criminal history points… (B) a prior 3-point offense… and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense.”

The “safety valve” was one of the only sensible things to come out of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the bill championed by then-Senator Joe Biden that, a quarter-century later, has been used to brand him a mass-incarcerating racist. The safety valve was intended to let people convicted of drug offenses as first-timers avoid the crushing mandatory minimum sentences that Congress had imposed on just about all drug dealing.

Eric Lopez got caught smuggling meth across the border. Everyone agreed he qualified for the safety valve except for his criminal history. Eric had one prior 3-point offense, and the government argued that was enough to disqualify him. Eric argued that the First Step Actamendment to the “safety valve” meant he had to have all three predicates: more than 4 points, one 3-point prior, and one 2-point prior violent offense.

Last week, the 9th Circuit agreed. In a decision that dramatically expands the reach of the safety valve, the Circuit applied the rules of statutory construction and held that the First Step amendment was unambiguous. “Put another way, we hold that ‘and’ means ‘and.’”

“We recognize that § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language might be viewed as a considerable departure from the prior version of § 3553(f)(1), which barred any defendant from safety-valve relief if he or she had more than one criminal-history point under the Sentencing Guidelines… As a result, § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language could possibly result in more defendants receiving safety-valve relief than some in Congress anticipated… But sometimes Congress uses words that reach further than some members of Congress may have expected… We cannot ignore Congress’s plain and unambiguous language just because a statute might reach further than some in Congress expected… Section 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language, the Senate’s own legislative drafting manual, § 3553(f)(1)’s structure as a conjunctive negative proof, and the canon of consistent usage result in only one plausible reading of § 3553(f)(1)’s“and” here: “And” is conjunctive. If Congress meant § 3553(f)(1)’s “and” to mean “or,” it has the authority to amend the statute accordingly. We do not.”

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

On December 21, 2018, President Donald Trump signed into law the 56-page First Step Act (S. 756), a bill that will usher in an array of reforms within the federal criminal justice system. The bill went to the president’s desk just days after passing the Senate on an 87-12 vote.

Seen by its proponents as a major policy victory, others have cautioned that – while a positive step in the right direction – the legislation still leaves much to be desired. From the most sinister lens, critics point out it will likely benefit the private prison industry while excluding certain prisoners from some of its beneficial provisions.

The First Step Act has 36 distinct sections which address many aspects of federal sentencing and prison-related policies. They range from placing prisoners in facilities closer to their families to sentencing reform and de-escalation training for guards, plus creating a risk and needs assessment system. The bill also calls for studies on medication-assisted opioid addiction treatment for prisoners, and an expansion and accompanying audit of Federal Prison Industries (UNICOR), the Bureau of Prisons’ industry work program.

“This legislation is what it says it is: a first step; and while it is an important first step, it is not comprehensive criminal justice reform,” the Caucus stated in a press release.

“This victory truly belongs to the thousands of people who, like me, have been personally impacted by incarceration and have dedicated their lives to improving the system,” said Jessica Jackson-Sloan, director and cofounder of #cut50.

While the First Step Act reduces mandatory minimum sentences for certain serious drug-related crimes, including “three strike” drug offenders, such reductions are not retroactive and thus do not apply to prisoners currently serving harsh mandatory minimums. Going forward, 20-year mandatory sentences imposed on repeat drug offenders will be changed to 15 years, while life sentences imposed on three-strike drug offenders will be reduced to 25 years.

The bill does make retroactive the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act, which addresses the crack vs. powder cocaine sentencing disparity. Under that law, the disparity in sentences imposed for crack vs. powder cocaine charges was reduced from 100-to-one to 18-to-one. [See: PLN, Sept. 2010, p.26]. That change will now be applied retroactively to thousands of prisoners, resulting in shorter sentences in many cases. The process is not automatic, though; prisoners must file a motion or the BOP, a federal prosecutor or federal court must take action to seek a sentence reduction.

Additionally, the federal safety valve provision, which provides an exception to mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders with little or no criminal history, was broadened in the First Step Act – though not made retroactive.

The bill also clarifies the good time credits that federal prisoners can earn, specifying that such credits shall be “up to 54 days for each year of the prisoner’s sentence imposed by the court.” Previously, the BOP limited good time to 47 days per year. This change will be retroactive for all BOP prisoners.

As part of the risk and needs assessment system created by the First Step Act, federal prisoners will be assigned to evidence-based recidivism reduction programs, with incentives for participation that include additional phone, video visit and in-person visitation privileges, and transfer to a facility closer to a prisoner’s home. Other potential incentives include increased commissary spending limits, “extended opportunities to access the [BOP’s secure] email system” and moves to preferred housing units.

One criticism of risk-assessment systems, which are typically based on algorithms that use personal data to calculate risk scores, is that they are subject to racial bias. Whether that will be a factor in the BOP’s risk-assessment system remains to be seen.

The First Step Act also contains several sections that deal with reentry, which were supported by private prison companies such as GEO Group and CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America). Those companies, which own numerous halfway houses and reentry centers that contract with government agencies, explained their support for the legislation in terms of helping prisoners get back on their feet upon their release.

“GEO’s political and governmental relations activities focus on promoting the use of public-private partnerships in the delivery of correctional services including evidence-based rehabilitation programs, both in-custody and post-release, aimed at reducing recidivism and helping the men and women in our care successfully reintegrate into their communities,” the company said in one of its federal lobbying disclosure forms.

For its part, CoreCivic – which owns dozens of community corrections facilities – also expressed support for the First Step Act, including in a December 19, 2018 press statement attributed to President and CEO Damon Hininger.

That national network of reentry centers was built to generate profit, of course, and both CoreCivic and GEO stand to benefit from the funding included in the First Step Act. Previously, both companies successfully opposed a shareholder resolution that would have required them to spend just five percent of their net profit on reentry and rehabilitative programs. [See: PLN, Feb. 2015, p.48].

Prison Legal News managing editor Alex Friedmann told The Intercept that “business as usual” for the private prison industry will still reign supreme under the First Step Act.

The topic of reentry appears in four sections of the bill. Management and Training Corporation (MTC), a competitor to GEO Group and CoreCivic, also came out in support of the First Step Act. MTC operates community corrections and reentry facilities too, and thus stands to benefit from the legislation and the $75 million it authorizes each year from 2019 through 2023 to fund reentry and rehabilitative programs for federal prisoners.

Another provision of the bill centers around solitary confinement of juvenile offenders. The First Step Act specifies that solitary “room confinement” can be used as a form of punishment, but only as a “temporary response to a covered juvenile’s behavior that poses a serious and immediate risk of physical harm to any individual, including the covered juvenile.”

In the context of the opioid epidemic, the First Step Act dictates that the BOP produce a report – to be submitted to the Committees on the Judiciary and Committees on Appropriations in both houses of Congress – which examines medication-assisted treatment and if it is a viable option for federal prisoners who have opioid and heroin addictions.

“In preparing the report, the [Bureau of Prisons] shall consider medication-assisted treatment as a strategy to assist in treatment where appropriate and not as a replacement for holistic and other drug-free approaches,” the bill explains. “The report shall include a description of plans to expand access to evidence-based treatment for heroin and opioid abuse for prisoners, including access to medication-assisted treatment in appropriate cases. Following submission, the [BOP] shall take steps to implement these plans.”

Within 120 days, the bill calls for a similar course of action by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. It requires the “Director of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts [to] submit to the Committees on the Judiciary and the Committees on Appropriations of the Senate and of the House of Representatives a report assessing the availability of and capacity for the provision of medication-assisted treatment for opioid and heroin abuse by treatment service providers serving prisoners who are serving a term of supervised release, and including a description of plans to expand access to medication-assisted treatment for heroin and opioid abuse whenever appropriate among prisoners under supervised release.”

One part of the First Step Act that largely flew under the radar expands the use of prison labor. Buried on page 49 of the bill is a section that could greatly expand federal prison industry programs and the market for products produced using prisoner labor.

Titled “Expanding Inmate Employment Through Federal Prison Industries,” the section allows for more vendors to purchase items manufactured by UNICOR, while also requiring the agency to be audited by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) within 90 days after the bill goes into effect.

The First Step Act allows products produced by UNICOR to be sold to “public entities for use in penal or correctional institutions,” “public entities for use in disaster relief or emergency response” and “the government of the District of Columbia.” Further, non-profit organizations can now purchase items directly from UNICOR.

“First Step would expand inmate employment through federal prison industries. These private companies employ incarcerated people in federal prisons and pay wages far below the federal minimum wage,” the organization wrote. “We are concerned about the expansion of prison industries because of the exploitative nature of these jobs and believe if these programs exist and are to be expanded, they should pay a fair wage.”

Pursuant to the First Step Act, the GAO will perform an “evaluation of the scope and size of the additional markets made available to Federal Prison Industries under this section [of the bill] and the total market value that would be opened up to Federal Prison Industries for competition with private sector providers of products and services.”

The GAO will also examine prisoner wages, doing so by “taking into account inmate productivity” while also evaluating whether UNICOR programs have a positive impact on recidivism rates once incarcerated workers are released.

The First Step Act includes a provision that bans the shackling of pregnant prisoners, “beginning on the date on which pregnancy is confirmed by a healthcare professional, and ending at the conclusion of postpartum recovery,” unless a prisoner poses “an immediate and serious threat of harm” to herself or others. All uses of restraints on pregnant prisoners must be reported.

All female prisoners will be provided free tampons and sanitary pads, “in a quantity that is appropriate to the healthcare needs of each prisoner.” While the BOP had announced in 2017 that it would provide feminine hygiene products to prisoners at no cost, the bill codifies that provision into law.

With respect to where prisoners are housed, and in a nod to the importance of family support during incarceration, the First Step Act states the BOP “shall designate the place of the prisoner’s imprisonment, and shall, subject to bed availability, the prisoner’s security designation, the prisoner’s programmatic needs, the prisoner’s mental and medical health needs, any request made by the prisoner related to faith-based needs, recommendations of the sentencing court, and other security concerns of the Bureau of Prisons, place the prisoner in a facility as close as practicable to the prisoner’s primary residence, and to the extent practicable, in a facility within 500 driving miles of that residence.”

The Correctional Officer Self-Protection Act, which was merged into the First Step Act, was drafted in response to the 2013 murder of BOP Lt. Osvaldo Albarati at the Metropolitan Detention Center, Guaynabo in Puerto Rico. Albarati was killed in a drive-by shooting after he finished his shift, reportedly in retribution for investigations he was conducting into cell phone smuggling at the facility.

Finally, among various other provisions – many of them technical in nature – the First Step Act reauthorizes the Second Chance Act, which provides funding for reentry programs and services, and includes improvements to the BOP’s compassionate release process – which has long been criticized. [See: PLN, Aug. 2018, p.58; Dec. 2014, p.50].

“It’s right there in the name: It’s called the First Step Act, acknowledging that it’s, well, a first step. The bill doesn’t end the war on drugs or mass incarceration. It won’t stop law enforcement from locking up nonviolent drug offenders. It doesn’t legalize marijuana. It doesn’t even end mandatory minimums or reduce prison sentences across the board, and it in fact only tweaks both,” Lopez wrote. “This isn’t to take away from the legislation or suggest that it wasn’t worth doing. Thousands of federal prison inmates will benefit from the bill. But it’s important to put the bill in a broader context – to not oversell its impact, and to acknowledge there’s still a lot more room to make America’s federal criminal justice system less punitive.”

It’s indeed a first step, one perhaps better described as a baby step. And it needs to be followed by a second step, third step and more – though the chances of additional criminal justice reform legislation being passed by Congress are exceedingly slim.

Sources: www.congress.gov, www.cnn.com, www.theintercept.com, www.bop.gov, www.prisonstudies.org, www.vox.com, www.unicor.gov, www.oversight.gov, www.wvnews.com, www.clasp.org, www.soprweb.senate.gov, www.opensecrets.org, www.mtctrains.com, www.c-span.org, www.cbc.house.gov, www.tampabay.com, www.lasentinel.net, www.theconversation.com, www.disclosures.house.gov, www.investors.geogroup.com, www.corecivic.com, www.theguardian.com, www.freedomworks.org, www.firststepact.org

On July 19, at least 2,200 federally incarcerated people are set to be released under the First Step Act, which was signed into law by President Donald Trump with support from both Republicans and Democrats. The legislation was spearheaded by #cut50, an initiative of The Dream Corps, aiming to reduce the number of people in our prisons and jails.

As part of the First Step Act, more than 1,600 inmates have qualified for a reduced sentence, while more than 1,100 have already been released, the Department of Justice told theAssociated Press.

When the legislation was first introduced last year, it faced criticism for not doing enough to reduce the length of prison sentences on the front end.

The provisions in the First Step Act go even further than the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which helped to reduce the disparity between crack and cocaine sentences on the federal level. The provisions in the First Step Act retroactively reduced the sentences of nearly 2,600 inmates not affected by the previous legislation.

“Yesterday, I met with someone who served 20 years in a life sentence, he was sentenced under the crack cocaine provision in 2005. He was released within a week after the First Step Act was signed into law,” Reed added.

The law also addresses the mandatory minimum sentences under federal law by expanding the “safety valve” judges use to avoid handing down mandatory minimum sentences in certain cases.

“To someone who has never been incarcerated, seven days may not seem like a lot, but if I had those extra seven days, I would have been released six months prior to my actual release date, which means I possibly could have intervened in my nephew"s shooting, which killed him,” Reed told BET.

“We’ve also created the "First Step to Second Chances" guide, which is 200 pages of resources on how to transition to life after prison,” Jackson told BET. “People leave with a bus ticket and $100, but a lot of people need support from somewhere else. This is why we are working with organizations that help with second chance hiring, creating job training programs, and working with companies who make donations, like the Lyft car ride donations Kim Kardashianannounced recently at the White House.”

"I"m so happy for the families that will be reunited today, but I can"t help but think back to the first few days after I was released from federal prison, after serving nearly 14 years inside,” Reed said in a statement to BET. “I was living with the consequences of a crime I committed and faced unimaginable barriers in not only supporting myself post-incarceration but also supporting my family. I know firsthand that when you’re released from prison, the hardest part is not what came before, but what lies ahead. It’s imperative that we come together as businesses, nonprofits, government agencies, and individuals to make sure that the men and women returning home today because of the First Step Act are set up to succeed.”

In short, not only is there no meaningful way for consumers to control how and when they are monitored online, companies are actively working to defeat consumer efforts to resist that monitoring. Currently, individuals who want privacy must attempt to win a technological arms race with the multi-billion dollar internet-advertising industry.

An ad-supported ecosystem of services can flourish without collecting massive quantities of data about individuals in secret and without their consent. Broadcast television stations were an extremely lucrative business throughout the second half of the 20th century, yet broadcasters were never privy to the intimate details of their audience members’ individual viewing habits. Insofar as television ads were targetable at all, it was not through “behavioral” targeting, but instead through good old-fashioned “contextual” targeting, in which ads are matched to the audiences that different shows attract. This is an effective means of targeting ads online, and one that is perfectly consistent with strong privacy protections. An advertiser that wants to reach golfers, for example, can place its ads on a site about golf or on pages returning the results for golf-related search terms.

In fact, such protections will establish predictability and stability of expectations that will enhance consumer confidence, prosperity, and innovation.

The transition to a paradigm where public safety does not depend exclusively or primarily on the police and the criminal justice system may be difficult. But a lesson can be taken from the transformation of the practice of medicine, which in recent years has come to emphasize holistic and preventive care. Instead of relying on surgical or other invasive interventions to treat illnesses and diseases, medicine now invests heavily in preventing illnesses by encouraging healthy lifestyles and addressing health issues early with noninvasive treatments.11 As former Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA) noted when Congress was considering the Affordable Care Act, a “truly transformational element” of the health care law was to “jump-start America’s transition from our current sick care system into a genuine health care system, one that is focused on keeping us healthy and out of the hospital in the first place.”12

That same type of transformation must happen with America’s approach to public safety. The criminal justice system can be likened to hospitalization or a surgical intervention, which is never removed as an option but is reserved for the most serious situations. Unnecessary arrests and incarcerations, like surgeries, run the risk of serious complications.13 Even when invasive interventions are necessary, care must always be taken during the procedure to minimize trauma and promote a quick recovery. But the overall goal and the bulk of resources should be devoted to keeping people out of the operating room or, in this case, out of the criminal justice system in the first place.

Unfortunately, the United States’ investments in public safety continue to overwhelmingly prioritize arrests and incarceration over measures that prevent crime from occurring. As elected leaders reflect on the 1994 crime bill, it is not enough to state that the country is learning lessons from the bill’s failings. Instead, elected leaders must take concrete action to halt the very mechanisms that the legislation created—and that continue to undercut meaningful criminal justice reform. Even the 1994 crime bill included a section devoted to crime prevention activities.14 But in the end, many of these programs were either repealed or never received any funding in the first place.15 Going forward, leaders must make the following commitments to stopping the ongoing harm inflicted by the 1994 crime bill.

Any serious effort to halt the ongoing damage wrought by the crime bill must target the money—the law’s primary vehicle for influencing state and local policy. Every year, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) distributes millions of dollars to states and localities through funding grants started under the crime bill—the vast majority of which is funneled directly to law enforcement agencies with few strings attached.16 The single largest source of federal public safety funding today is the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) Program, which has its roots in a massive mid-1990s block grant for local law enforcement agencies.17 Cities and states can use JAG to support a wide array of public safety functions—from violence prevention to indigent defense to mental health treatment.18 The reality, however, is that most JAG funds go directly to law enforcement.

JAG and other public safety dollars from the federal government cannot continue to be structured in a way that results in the vast majority of the funds going to support law enforcement. The federal government must intentionally invest in a new vision for stronger, healthier communities and no longer simply distribute money to states with the hope that they spend it appropriately. This can be accomplished in part by requiring states to devote substantial percentages of JAG funds to areas besides law enforcement in order to ensure a comprehensive approach to public safety. Additionally, Congress could change the eligibility formula for receiving JAG funds so that it is based not only on population and annual crime rate data, but also on other indicators of community well-being such as measures of poverty, unemployment, and educational attainment rates. Congress could also substantially increase the amounts that it appropriates to JAG—but only if that escalation is set aside for purpose areas that are perpetually underfunded by public safety dollars such as crime prevention and mental health and substance abuse treatment. Through a radical realignment of DOJ’s investments, lawmakers can reinvest billions of dollars into communities and effectively reshape the way that jurisdictions think about and carry out public safety efforts.

Enacting laws that authorize the incarceration of individuals is one of the most powerful and impactful responsibilities of legislators and elected leaders. Yet, Congress has not been shy—or particularly deliberative—about wielding this authority. The federal criminal code contains offenses and criminal penalties that are too numerous for experts to count. Recent estimates combining research from several sources show that approximately 5,000 federal statutes carry a criminal penalty—a 50 percent increase in the number of federal crimes since the 1980s.25 Already in the 116th Congress, which is less than three months old, lawmakers have introduced nearly 200 pieces of legislation that add or amend federal criminal statutes, and only a handful of them—for example, the Justice Safety Valve Act—are intended to reduce criminal penalties.26

For federal lawmakers, there are virtually no barriers to passing a new criminal statute or increasing a criminal penalty. Congress is under no requirement to know whether a new statute is necessary; if the increased penalties would deter or prevent future crimes; or what population would be affected most by the new statute. Even traditional procedures for any legislation such as conducting hearings and voting a bill out of a committee have been bypassed when deemed necessary. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, for instance, was another landmark tough-on-crime statute that infamously established the 100-to-1 powder versus crack cocaine sentencing disparity.27 That bill was introduced and signed into law within a span of just two months. According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission:

The sentencing provisions of the Act were initiated in August 1986, following the July 4th congressional recess during which public concern and media coverage of cocaine peaked as a result of the June 1986 death of NCAA basketball star Len Bias. Apparently because of the heightened concern, Congress dispensed with much of the deliberative legislative process, including committee hearings.28

The 1994 crime bill accelerated the U.S. prison boom by authorizing more than $12 billion to subsidize the construction of state correctional facilities, giving priority to states that enacted so-called truth-in-sentencing laws.29 These laws, which require individuals to serve at least 85 percent of their sentence behind bars, have been shown to expand prison populations by increasing individuals’ length of stay.30 By 1998, truth-in-sentencing laws were in effect in 27 states, up from eight states before the crime bill’s passage. A majority of state officials cited the federal incentives as a driving force for adopting the truth-in-sentencing policy change.31 In the decade following the crime bill’s enactment, the number of correctional facilities nationwide jumped by 20 percent.32 The incarcerated population grew by 40 percent during the same period.33

S. 3649 was sponsored by Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.), and 22 other senators. The prison reform provisions in S. 3649 are similar to those in H.R. 5682, legislation sponsored by Reps. Doug Collins (R-Ga.), Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) and 17 cosponsors that overwhelmingly passed the House in May. While both bills include various prison reforms, the Senate version also includes some provisions based on sentencing reforms that were included in S. 1917, comprehensive legislation approved in February by the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Known as the First Step Act, both S. 3649 and H.R. 5682 would require the Bureau of Prisons to implement a recidivism-reduction program that would allow eligible prisoners to earn credits toward alternative custody arrangements as they approach the end of their sentences. This would include halfway houses or home confinement.

Sentencing provisions included in S. 3649 would prospectively narrow the scope of mandatory minimum sentences to focus on the most serious drug offenders and violent criminals and expand the existing “safety valve” that allows judges to use discretion in sentencing lower-level nonviolent offenders. The bill also would ensure retroactive application of provisions in the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced disparity in sentencing between crack and powder cocaine offenses.

Both S. 3649 and H.R. 5682 include provisions to increase the use and transparency of compassionate release for elderly and terminally ill prisoners.

Other provisions would prevent the use of restraints on prisoners throughout pregnancy and postpartum recovery and would impose limits on the use of solitary confinement for juveniles.

Although President Trump signaled strong support for the First Step Act, the legislation’s future is in doubt. Opponents of the bill have expressed concerns about the mandatory minimum sentencing provisions, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has stated that more pressing matters need to be addressed during the brief lame duck session.

During the 115th Congress, the ABA has supported the more comprehensive sentencing/corrections approach taken by the earlier Senate bill, S. 1917, but the association has policies supporting many of the prison reform provisions in the new version of the legislation.

In one of Congress’s last acts before the government shutdown, it passed, and the president signed, the First Step Act of 2018 (the act). The act represents progress toward reducing the rate of mass incarceration and ameliorating the extensive personal and societal problems it has caused. Its successful passage was the result of years of lobbying by a coalition of left and right-wing activists and leaders (and a Kardashian) working together to start reducing a prison population inflated by over-criminalization and over-penalization.

Broadly viewed, the act is intended to achieve its aims in two principal respects: first, on the front end, by modifying sentencing laws, including reducing the application of certain mandatory minimum sentences; and second, on the back end, by providing for various re-entry services for returning citizens. While the bulk of the act is targeted toward this latter goal of reducing recidivism, its sentencing modifications, although few, are significant and will have practical effects.

The act is somewhat limited in scope as it only applies to those charged with or serving sentences for federal offenses. It will have no application to the substantial number of individuals incarcerated for violations of state law. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice statistics, there are approximately 2.2 million individuals incarcerated in local, state or federal prisons. Of that total, approximately 215,000—9.7 percent—are in the federal system. It is expected that the act’s retroactive provisions will affect only about 1.5 percent of current federally detained individuals charged with drug and drug-related offenses. However, going forward, these provisions will impact about 12,000 cases per year involving over 25,000 defendants. Thus, in practice, the act will have a measurable impact.

The sentencing modifications set forth in the act can be best illustrated with an example. In our example, the case begins with law enforcement buying a kilogram of heroin from Individual A. At the time of this operation, law enforcement observes Individual A with a firearm. After buying the heroin, law enforcement obtains a search warrant for Individual A’s residence and finds another firearm in close proximity to tools used to weigh and package drugs. Based on these facts the U.S. Attorney’s Office charges Individual A with one count of distribution of one kilogram or more of heroin, and two counts of possession of a firearm in furtherance of a drug trafficking offense. Individual A, who was previously convicted of possession with intent to distribute a small amount of marijuana and received a sentence of time-served (70 days) in 1998, pleads guilty, and begins preparing for sentencing.

Prior to passage of the First Step Act, Individual A could have received a mandatory minimum sentence of 50 years incarceration. The federal drug laws call for a mandatory minimum sentence of 10 years for distribution of one kilogram or more of heroin. But because Individual A already has a prior conviction for a felony drug offense, he could be sentenced to mandatory minimum sentence of 20 years. Individual A’s possession of the two guns further increases the potential mandatory minimum sentence. A single count of possession of a firearm in furtherance of a drug trafficking crime carries a five-year sentence that must be served consecutively to any other sentence of imprisonment. But federal law provides that a second count of the same charge carries a 25-year consecutive sentence that must be “stacked” to the five years sentence for the first count and the sentence for the underlying drug count. In this scenario, a federal judge would have no discretion and must sentence Individual A to a sentence of imprisonment of at least 50 years.

Two points require emphasizing at this stage concerning charging and sentencing discretion. First, the decision to charge a defendant with multiple counts of possession of a firearm in furtherance of a drug trafficking crime is within the discretion of the prosecuting U.S. Attorney. Second, the U.S. Attorney also has discretion to file, or not file, an “information” charging Individual A with a prior felony drug conviction. This discretion, however, is limited by current Department of Justice policy, set forth in the May 10, 2017, memorandum from former Attorney General Jeff Sessions to all federal prosecutors that “it is a core principle that prosecutors should charge and pursue the most serious, readily provable offense ... which are those that carry the most substantial guidelines sentence, including mandatory minimum sentences.” Under the Sessions Memorandum, federal prosecutors are effectively required to pursue all available mandatory minimum sentences.

The act dramatically changes this result with key amendments to: application of the prior felony/drug conviction enhancement in 21 U.S.C. Section 841; the government’s ability to “stack” charges under 18 U.S.C. Section 924; and the potential availability of the safety valve provision.

Whereas under existing law Individual A faced an additional 10-year statutory enhancement for his prior felony drug conviction, the act replaces “prior conviction for a felony drug offense” with “prior conviction for a serious drug felony or serious violent felony.” The act defines “serious drug felony” to mean an offense for which “the offender served a term of imprisonment of more than 12 months” and “the offender’s release from any term of imprisonment was within 15 years of the commencement of the instant offense.” Under the act, a relevant prior offense can now grow stale and it must have included a material term of incarceration. Moreover, even if triggered, this enhancement as modified by the act would result in the imposition of a mandatory 15-year term of incarceration. Additionally, while existing law contains a “three strikes” provision mandating life in prison for anyone convicted of a third drug offense, the act reduces that mandatory minimum to 25 years. Finally, this amendment includes limited retroactivity, applying to “any offense that was committed before the date of enactment of this act, if a sentence for the offense has not been imposed as of such date of enactment.”

The act makes a small but significant change to the firearm enhancement to eliminate the stacking of charges. The act amends Section 924 to make clear that the 25-year enhancement applies only to subsequent convictions in separate cases. Put succinctly, whereas Individual A previously would have faced a mandatory sentence of 30 years for the two gun charges, he now would face a mandatory term of only five years for those charges. Altogether, the act would reduce the mandatory minimum sentence Individual A faces from 50 years imprisonment to a mandatory 15 years imprisonment.

The act also expands the so-called “safety valve” provision. Previously, a defendant convicted of a drug crime could escape the mandatory minimum provisions if he had an insignificant criminal history; did not use violence or a firearm in the subject offense; was not a leader or organizer of a criminal enterprise; and fully accepted responsibility for the offense. The act modifies the safety valve to provide sentencing judges with greater discretion whether to apply a mandatory minimum sentence by making the safety valve available more widely. This provision is now available to defendants who have had prior convictions. The defendant must, of course, meet all of the other existing requirements. In our example, Individual A would remain subject to the statutory mandatory minimum sentences because the government has charged him with firearm offenses. However, if the prosecutor declined to bring or withdrew the gun charge, Individual A would become eligible for the safety valve. Individual A has served a single prior sentence of 70-day incarceration, which would have made him ineligible for the safety valve under existing law. Under the guidelines, this calculates to two criminal history points, thus the sentencing judge would be able to sentence Individual A without regard to the mandatory minimum sentences otherwise applicable to his offenses. Because of the act’s changes, a sentencing judge would now be freed to sentence Individual A to a sentence less than the mandatory minimum.

As shown, in certain cases the act will yield substantial changes from existing law. It is a real and important "First Step" toward sentencing reform.

David L. Axelrodis a partner at Ballard Spahr. His practice focuses on representing companies and individuals under investigation by government agencies, including the U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, concerning alleged violations of state and federal law, including securities laws and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), as well as antitrust matters.

8613371530291

8613371530291