first step act safety valve provision price

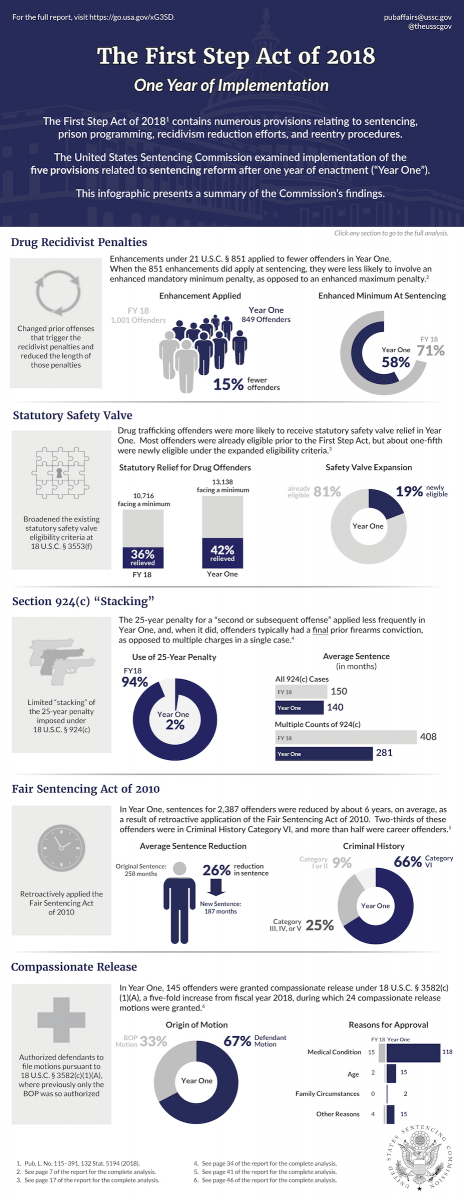

A “safety valve” is an exception to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. A safety valve allows a judge to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum term if certain conditions are met. Safety valves can be broad or narrow, applying to many or few crimes (e.g., drug crimes only) or types of offenders (e.g., nonviolent offenders). They do not repeal or eliminate mandatory minimum sentences. However, safety valves save taxpayers money because they allow courts to give shorter, more appropriate prison sentences to offenders who pose less of a public safety threat. This saves our scarce taxpayer dollars and prison beds for those who are most deserving of the mandatory minimum term and present the biggest danger to society.

The Problem:Under current federal law, there is only one safety valve, and it applies only to first-time, nonviolent drug offenders whose cases did not involve guns. FAMM was instrumental in the passage of this safety valve, in 1994. Since then, more than 95,000 nonviolent drug offenders have received fairer sentences because of it, saving taxpayers billions. But it is a very narrow exception: in FY 2015, only 13 percent of all drug offenders qualified for the exception.

Mere presence of even a lawfully purchased and registered gun in a person’s home or car is enough to disqualify a nonviolent drug offender from the safety valve,

Even very minor prior infractions (e.g., careless driving) that resulted in no prison time can disqualify an otherwise worthy low-level drug offender from the safety valve, and

The Solution:Create a broader safety valve that applies to all mandatory minimum sentences, and expand the existing drug safety valve to cover more low-level offenders.

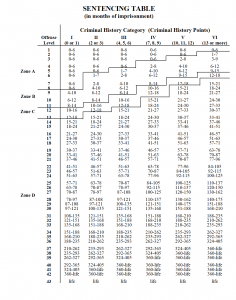

The Federal Safety Valve law permits a sentence in a drug conviction to go below the mandatory drug crime minimums for certain individuals that have a limited prior criminal history. This is a great benefit for those who want a second chance at life without sitting around incarcerated for many years. Prior to the First Step Act, if the defendant had more than one criminal history point, then they were ineligible for safety valve. The First Step Act changed this, now allowing for up to four prior criminal history points in certain circumstances.

The First Step Act now gives safety valve eligibility if: (1) the defendant does not have more than four prior criminal history points, excluding any points incurred from one point offenses; (2) a prior three point offense; and (3) a prior two point violent offense. This change drastically increased the amount of people who can minimize their mandatory sentence liability.

Understanding how safety valve works in light of the First Step Act is extremely important in how to incorporate these new laws into your case strategy. For example, given the increase in eligible defendants, it might be wise to do a plea if you have a favorable judge who will likely sentence to lesser time. Knowing these minute issues is very important and talking to a lawyer who is an experienced federal criminal defense attorney in southeast Michigan is what you should do. We are experienced federal criminal defense attorneys and would love to help you out. Contact us today.

“Mandatory minimum sentences are also unlikely to reduce crime by incapacitation, at least given the overbreadth of such laws and their failure to focus on those most likely to recidivate. Among other things, offenders typically age out of the criminal lifestyle, usually in their 30s, meaning that long mandatory sentences may require the continued incarceration of individuals who would not be engaged in crime. In such cases, the extra years of imprisonment will not incapacitate otherwise active criminals and thus will not result in reduced crime. … Moreover, certain offenses subject to mandatory minimums can draw upon a large supply of potential participants. With drug organizations, for instance, an arrested dealer or courier may be quickly replaced by another, eliminating any crime-reduction benefit. More generally, any incapacitation-based effect from mandatory minimums was likely achieved years ago, due to the diminishing marginal returns of locking more people up in an age of mass incarceration. Based on the foregoing arguments and others, most scholars have rejected crime-control arguments for mandatory sentencing laws. By virtually all measures, there is no reason to believe that mandatory minimums have any meaningful impact on crime rates.”

“The conclusion that increasing already long sentences has no material deterrent effect also has implications for mandatory minimum sentencing. Mandatory minimum sentence statutes have two distinct properties. One is that they typically increase already long sentences, which we have concluded is not an effective deterrent. Second, by mandating incarceration, they also increase the certainty of imprisonment given conviction. Because, as discussed earlier, the certainty of conviction even following commission of a felony is typically small, the effect of mandatory minimum sentencing on certainty of punishment is greatly diminished. Furthermore, as discussed at length by Nagin (2013a, 2013b), all of the evidence on the deterrent effect of certainty of punishment pertains to the deterrent effect of the certainty of apprehension, not to the certainty of postarrest outcomes (including certainty of imprisonment given conviction). Thus, there is no evidence one way or the other on the deterrent effect of the second distinguishing characteristic of mandatory minimum sentencing (Nagin, 2013a, 2013b).”

Tonry, Michael. “Fifty Years of American Sentencing Reform — Nine Lessons.” 7 Dec. 2018, Crime and Justice—A Review of Research. Forthcoming. Available at SSRN:https://ssrn.com/abstract=3297777

“Mandatory Sentences. Mandatory sentencing laws should be repealed, and no new ones enacted; they produce countless injustices, encourage cynical circumventions, and seldom achieve demonstrable reductions in crime.

“Mandatory sentencing laws are a fundamentally bad idea. From eighteenth century England, when pickpockets worked the crowds at hangings of pickpockets and juries refused to convict people of offenses subject to severe punishments, to twenty-first century America, the evidence has been clear. Mandatory minimum sentences have few if any discernible deterrent effects and, because of their rigidity, result in unjustly harsh punishments in many cases and willful circumvention by prosecutors, judges, and juries in others. In our time, when plea bargaining is ubiquitous, mandatories are routinely used to coerce guilty pleas, sometimes from innocent people (Johnson 2019).

‘Knowledge about mandatory minimum sentences has changed remarkably little in the past 30 years. Their ostensible primary rationale is deterrence. The overwhelming weight of the evidence, however, shows that they have few if any deterrent effects … Existing knowledge is too fragmentary [and] estimated effects are so small or contingent on particular circumstances as to have no practical relevance for policy making. (Travis, Western, and Redburn 2014, p. 83)’

“Contemporary research thus confirms longstanding cautions against enactment of mandatory sentencing laws. Their use to coerce guilty pleas is new and distinctive to our times. Even innocent defendants are sorely tempted to plead guilty and accept probation or a short prison term rather than risk a mandatory 10- or 20-year sentence. The late Harvard Law School professor William Stuntz observed that ‘outside the plea-bargaining process’ prosecutors’ threats to file charges subject to mandatories ‘would be deemed extortionate’ (2011, p. 260). Federal Court of Appeals judge Gerald Lynch similarly observed that prosecutors’ power to threaten mandatories has enabled them to displace judges from their traditional role: It is ‘the prosecutor who decides what sentence the defendant should be given in exchange for his plea’ (2003, p. 1404). American sentencing has become more severe in recent decades; prosecutors bear much of the responsibility (Johnson 2019).

“Every authoritative law reform organization that has examined American sentencing in the last 50 years has proposed elimination of mandatory minimum sentence laws. These included, in earlier times, the 1967 President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, the 1971 National Commission on Reform of Federal Laws, the 1973 National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, the 1979 Model Sentencing and Corrections Act proposed by the Uniform Law Commissioners, and the American Bar Association’s 1994 Sentencing Standards. The American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code—Sentencing offered the same recommendation in 2017 (Reitz and Klingele 2019).”

Considerable empirical research has shown that racial disparities in sentencing are pervasive: “one of every nine black men between the ages of twenty and thirty-four is behind bars.” In United States v. Booker, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered the mandatory guidelines merely advisory. This study, looking not just at judicial opinions but also at plea agreements, charging decisions, and other factors contributing to sentencing, shows that this racial disparity has actually not increased since more judicial discretion was permitted. Instead, the black-white gap in sentencing “appears to stem largely from prosecutors’ charging choices, especially to charge defendants with ‘mandatory minimum’ offenses.” Removing these minimums as advisory guidelines would help shift toward greater racial equalization in the sentencing arena.

“Despite substantial expenditures on longer prison terms for drug offenders, taxpayers have not realized a strong public safety return. The self-reported use of illegal drugs has increased over the long term as drug prices have fallen and purity has risen. Federal sentencing laws that were designed with serious traffickers in mind have resulted in lengthy imprisonment of offenders who played relatively minor roles. These laws also have failed to reduce recidivism. Nearly a third of the drug offenders who leave federal prison and are placed on community supervision commit new crimes or violate the conditions of their release—a rate that has not changed substantially in decades.”

8613371530291

8613371530291