how to adjust safety valve free sample

In order to ensure that the maximum allowable accumulation pressure of any system or apparatus protected by a safety valve is never exceeded, careful consideration of the safety valve’s position in the system has to be made. As there is such a wide range of applications, there is no absolute rule as to where the valve should be positioned and therefore, every application needs to be treated separately.

A common steam application for a safety valve is to protect process equipment supplied from a pressure reducing station. Two possible arrangements are shown in Figure 9.3.3.

The safety valve can be fitted within the pressure reducing station itself, that is, before the downstream stop valve, as in Figure 9.3.3 (a), or further downstream, nearer the apparatus as in Figure 9.3.3 (b). Fitting the safety valve before the downstream stop valve has the following advantages:

• The safety valve can be tested in-line by shutting down the downstream stop valve without the chance of downstream apparatus being over pressurised, should the safety valve fail under test.

• When setting the PRV under no-load conditions, the operation of the safety valve can be observed, as this condition is most likely to cause ‘simmer’. If this should occur, the PRV pressure can be adjusted to below the safety valve reseat pressure.

Indeed, a separate safety valve may have to be fitted on the inlet to each downstream piece of apparatus, when the PRV supplies several such pieces of apparatus.

• If supplying one piece of apparatus, which has a MAWP pressure less than the PRV supply pressure, the apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve, preferably close-coupled to its steam inlet connection.

• If a PRV is supplying more than one apparatus and the MAWP of any item is less than the PRV supply pressure, either the PRV station must be fitted with a safety valve set at the lowest possible MAWP of the connected apparatus, or each item of affected apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve.

• The safety valve must be located so that the pressure cannot accumulate in the apparatus viaanother route, for example, from a separate steam line or a bypass line.

It could be argued that every installation deserves special consideration when it comes to safety, but the following applications and situations are a little unusual and worth considering:

• Fire - Any pressure vessel should be protected from overpressure in the event of fire. Although a safety valve mounted for operational protection may also offer protection under fire conditions,such cases require special consideration, which is beyond the scope of this text.

• Exothermic applications - These must be fitted with a safety valve close-coupled to the apparatus steam inlet or the body direct. No alternative applies.

• Safety valves used as warning devices - Sometimes, safety valves are fitted to systems as warning devices. They are not required to relieve fault loads but to warn of pressures increasing above normal working pressures for operational reasons only. In these instances, safety valves are set at the warning pressure and only need to be of minimum size. If there is any danger of systems fitted with such a safety valve exceeding their maximum allowable working pressure, they must be protected by additional safety valves in the usual way.

In order to illustrate the importance of the positioning of a safety valve, consider an automatic pump trap (see Block 14) used to remove condensate from a heating vessel. The automatic pump trap (APT), incorporates a mechanical type pump, which uses the motive force of steam to pump the condensate through the return system. The position of the safety valve will depend on the MAWP of the APT and its required motive inlet pressure.

This arrangement is suitable if the pump-trap motive pressure is less than 1.6 bar g (safety valve set pressure of 2 bar g less 0.3 bar blowdown and a 0.1 bar shut-off margin). Since the MAWP of both the APT and the vessel are greater than the safety valve set pressure, a single safety valve would provide suitable protection for the system.

However, if the pump-trap motive pressure had to be greater than 1.6 bar g, the APT supply would have to be taken from the high pressure side of the PRV, and reduced to a more appropriate pressure, but still less than the 4.5 bar g MAWP of the APT. The arrangement shown in Figure 9.3.5 would be suitable in this situation.

Here, two separate PRV stations are used each with its own safety valve. If the APT internals failed and steam at 4 bar g passed through the APT and into the vessel, safety valve ‘A’ would relieve this pressure and protect the vessel. Safety valve ‘B’ would not lift as the pressure in the APT is still acceptable and below its set pressure.

It should be noted that safety valve ‘A’ is positioned on the downstream side of the temperature control valve; this is done for both safety and operational reasons:

Operation - There is less chance of safety valve ‘A’ simmering during operation in this position,as the pressure is typically lower after the control valve than before it.

Also, note that if the MAWP of the pump-trap were greater than the pressure upstream of PRV ‘A’, it would be permissible to omit safety valve ‘B’ from the system, but safety valve ‘A’ must be sized to take into account the total fault flow through PRV ‘B’ as well as through PRV ‘A’.

A pharmaceutical factory has twelve jacketed pans on the same production floor, all rated with the same MAWP. Where would the safety valve be positioned?

One solution would be to install a safety valve on the inlet to each pan (Figure 9.3.6). In this instance, each safety valve would have to be sized to pass the entire load, in case the PRV failed open whilst the other eleven pans were shut down.

If additional apparatus with a lower MAWP than the pans (for example, a shell and tube heat exchanger) were to be included in the system, it would be necessary to fit an additional safety valve. This safety valve would be set to an appropriate lower set pressure and sized to pass the fault flow through the temperature control valve (see Figure 9.3.8).

A safety valve must always be sized and able to vent any source of steam so that the pressure within the protected apparatus cannot exceed the maximum allowable accumulated pressure (MAAP). This not only means that the valve has to be positioned correctly, but that it is also correctly set. The safety valve must then also be sized correctly, enabling it to pass the required amount of steam at the required pressure under all possible fault conditions.

Once the type of safety valve has been established, along with its set pressure and its position in the system, it is necessary to calculate the required discharge capacity of the valve. Once this is known, the required orifice area and nominal size can be determined using the manufacturer’s specifications.

In order to establish the maximum capacity required, the potential flow through all the relevant branches, upstream of the valve, need to be considered.

In applications where there is more than one possible flow path, the sizing of the safety valve becomes more complicated, as there may be a number of alternative methods of determining its size. Where more than one potential flow path exists, the following alternatives should be considered:

This choice is determined by the risk of two or more devices failing simultaneously. If there is the slightest chance that this may occur, the valve must be sized to allow the combined flows of the failed devices to be discharged. However, where the risk is negligible, cost advantages may dictate that the valve should only be sized on the highest fault flow. The choice of method ultimately lies with the company responsible for insuring the plant.

For example, consider the pressure vessel and automatic pump-trap (APT) system as shown in Figure 9.4.1. The unlikely situation is that both the APT and pressure reducing valve (PRV ‘A’) could fail simultaneously. The discharge capacity of safety valve ‘A’ would either be the fault load of the largest PRV, or alternatively, the combined fault load of both the APT and PRV ‘A’.

This document recommends that where multiple flow paths exist, any relevant safety valve should, at all times, be sized on the possibility that relevant upstream pressure control valves may fail simultaneously.

The supply pressure of this system (Figure 9.4.2) is limited by an upstream safety valve with a set pressure of 11.6 bar g. The fault flow through the PRV can be determined using the steam mass flow equation (Equation 3.21.2):

Once the fault load has been determined, it is usually sufficient to size the safety valve using the manufacturer’s capacity charts. A typical example of a capacity chart is shown in Figure 9.4.3. By knowing the required set pressure and discharge capacity, it is possible to select a suitable nominal size. In this example, the set pressure is 4 bar g and the fault flow is 953 kg/h. A DN32/50 safety valve is required with a capacity of 1 284 kg/h.

Where sizing charts are not available or do not cater for particular fluids or conditions, such as backpressure, high viscosity or two-phase flow, it may be necessary to calculate the minimum required orifice area. Methods for doing this are outlined in the appropriate governing standards, such as:

The methods outlined in these standards are based on the coefficient of discharge, which is the ratio of the measured capacity to the theoretical capacity of a nozzle with an equivalent flow area.

Coefficients of discharge are specific to any particular safety valve range and will be approved by the manufacturer. If the valve is independently approved, it is given a ‘certified coefficient of discharge’.

This figure is often derated by further multiplying it by a safety factor 0.9, to give a derated coefficient of discharge. Derated coefficient of discharge is termed Kdr= Kd x 0.9

Critical and sub-critical flow - the flow of gas or vapour through an orifice, such as the flow area of a safety valve, increases as the downstream pressure is decreased. This holds true until the critical pressure is reached, and critical flow is achieved. At this point, any further decrease in the downstream pressure will not result in any further increase in flow.

A relationship (called the critical pressure ratio) exists between the critical pressure and the actual relieving pressure, and, for gases flowing through safety valves, is shown by Equation 9.4.2.

For gases, with similar properties to an ideal gas, ‘k’ is the ratio of specific heat of constant pressure (cp) to constant volume (cv), i.e. cp : cv. ‘k’ is always greater than unity, and typically between 1 and 1.4 (see Table 9.4.8).

Overpressure - Before sizing, the design overpressure of the valve must be established. It is not permitted to calculate the capacity of the valve at a lower overpressure than that at which the coefficient of discharge was established. It is however, permitted to use a higher overpressure (see Table 9.2.1, Module 9.2, for typical overpressure values). For DIN type full lift (Vollhub) valves, the design lift must be achieved at 5% overpressure, but for sizing purposes, an overpressure value of 10% may be used.

For liquid applications, the overpressure is 10% according to AD-Merkblatt A2, DIN 3320, TRD 421 and ASME, but for non-certified ASME valves, it is quite common for a figure of 25% to be used.

The ASME/API RP 520 and EN ISO 4126 standards, however, require an additional backpressure correction factor to be determined and then incorporated in the relevant equation.

Two-phase flow - When sizing safety valves for boiling liquids (e.g. hot water) consideration must be given to vaporisation (flashing) during discharge. It is assumed that the medium is in liquid state when the safety valve is closed and that, when the safety valve opens, part of the liquid vaporises due to the drop in pressure through the safety valve. The resulting flow is referred to as two-phase flow.

The required flow area has to be calculated for the liquid and vapour components of the discharged fluid. The sum of these two areas is then used to select the appropriate orifice size from the chosen valve range. (see Example 9.4.3)

A little product education can make you look super smart to customers, which usually means more orders for everything you sell. Here’s a few things to keep in mind about safety valves, so your customers will think you’re a genius.

A safety valve is required on anything that has pressure on it. It can be a boiler (high- or low-pressure), a compressor, heat exchanger, economizer, any pressure vessel, deaerator tank, sterilizer, after a reducing valve, etc.

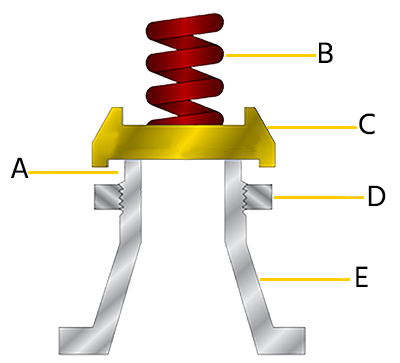

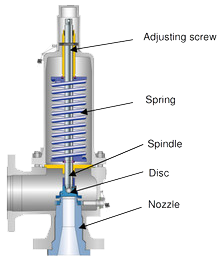

There are four main types of safety valves: conventional, bellows, pilot-operated, and temperature and pressure. For this column, we will deal with conventional valves.

A safety valve is a simple but delicate device. It’s just two pieces of metal squeezed together by a spring. It is passive because it just sits there waiting for system pressure to rise. If everything else in the system works correctly, then the safety valve will never go off.

A safety valve is NOT 100% tight up to the set pressure. This is VERY important. A safety valve functions a little like a tea kettle. As the temperature rises in the kettle, it starts to hiss and spit when the water is almost at a boil. A safety valve functions the same way but with pressure not temperature. The set pressure must be at least 10% above the operating pressure or 5 psig, whichever is greater. So, if a system is operating at 25 psig, then the minimum set pressure of the safety valve would be 30 psig.

Most valve manufacturers prefer a 10 psig differential just so the customer has fewer problems. If a valve is positioned after a reducing valve, find out the max pressure that the equipment downstream can handle. If it can handle 40 psig, then set the valve at 40. If the customer is operating at 100 psig, then 110 would be the minimum. If the max pressure in this case is 150, then set it at 150. The equipment is still protected and they won’t have as many problems with the safety valve.

Here’s another reason the safety valve is set higher than the operating pressure: When it relieves, it needs room to shut off. This is called BLOWDOWN. In a steam and air valve there is at least one if not two adjusting rings to help control blowdown. They are adjusted to shut the valve off when the pressure subsides to 6% below the set pressure. There are variations to 6% but for our purposes it is good enough. So, if you operate a boiler at 100 psig and you set the safety valve at 105, it will probably leak. But if it didn’t, the blowdown would be set at 99, and the valve would never shut off because the operating pressure would be greater than the blowdown.

All safety valves that are on steam or air are required by code to have a test lever. It can be a plain open lever or a completely enclosed packed lever.

Safety valves are sized by flow rate not by pipe size. If a customer wants a 12″ safety valve, ask them the flow rate and the pressure setting. It will probably turn out that they need an 8×10 instead of a 12×16. Safety valves are not like gate valves. If you have a 12″ line, you put in a 12″ gate valve. If safety valves are sized too large, they will not function correctly. They will chatter and beat themselves to death.

Safety valves need to be selected for the worst possible scenario. If you are sizing a pressure reducing station that has 150 psig steam being reduced to 10 psig, you need a safety valve that is rated for 150 psig even though it is set at 15. You can’t put a 15 psig low-pressure boiler valve after the reducing valve because the body of the valve must to be able to handle the 150 psig of steam in case the reducing valve fails.

The seating surface in a safety valve is surprisingly small. In a 3×4 valve, the seating surface is 1/8″ wide and 5″ around. All it takes is one pop with a piece of debris going through and it can leak. Here’s an example: Folgers had a plant in downtown Kansas City that had a 6×8 DISCONTINUED Consolidated 1411Q set at 15 psig. The valve was probably 70 years old. We repaired it, but it leaked when plant maintenance put it back on. It was after a reducing valve, and I asked him if he played with the reducing valve and brought the pressure up to pop the safety valve. He said no, but I didn’t believe him. I told him the valve didn’t leak when it left our shop and to send it back.

If there is a problem with a safety valve, 99% of the time it is not the safety valve or the company that set it. There may be other reasons that the pressure is rising in the system before the safety valve. Some ethanol plants have a problem on starting up their boilers. The valves are set at 150 and they operate at 120 but at startup the pressure gets away from them and there is a spike, which creates enough pressure to cause a leak until things get under control.

If your customer is complaining that the valve is leaking, ask questions before a replacement is sent out. What is the operating pressure below the safety valve? If it is too close to the set pressure then they have to lower their operating pressure or raise the set pressure on the safety valve.

Is the valve installed in a vertical position? If it is on a 45-degree angle, horizontal, or upside down then it needs to be corrected. I have heard of two valves that were upside down in my 47 years. One was on a steam tractor and the other one was on a high-pressure compressor station in the New Mexico desert. He bought a 1/4″ valve set at 5,000 psig. On the outlet side, he left the end cap in the outlet and put a pin hole in it so he could hear if it was leaking or not. He hit the switch and when it got up to 3,500 psig the end cap came flying out like a missile past his nose. I told him to turn that sucker in the right direction and he shouldn’t have any problems. I never heard from him so I guess it worked.

If the set pressure is correct, and the valve is vertical, ask if the outlet piping is supported by something other than the safety valve. If they don’t have pipe hangers or a wall or something to keep the stress off the safety valve, it will leak.

There was a plant in Springfield, Mo. that couldn’t start up because a 2″ valve was leaking on a tank. It was set at 750 psig, and the factory replaced it 5 times. We are not going to replace any valves until certain questions are answered. I was called to solve the problem. The operating pressure was 450 so that wasn’t the problem. It was in a vertical position so we moved on to the piping. You could tell the guy was on his cell phone when I asked if there was any piping on the outlet. He said while looking at the installation that he had a 2″ line coming out into a 2×3 connection going up a story into a 3×4 connection and going up another story. I asked him if there was any support for this mess, and he hung up the phone. He didn’t say thank you, goodbye, or send me a Christmas present.

Pipe dope is another problem child. Make sure your contractors ease off on the pipe dope. That is enough for today, class. Thank you for your patience. And thank you for your business.

Safety relief valves are relatively maintenance-free devices. Even so, it is recommended that a periodic inspection of these devices be done every six to 12 months.

A common maintenance error is to add a second relief valve onto the outlet of an existing relief valve that is leaking. This “stacking” of relief valves is not permissible by code.

By installing two relief valves in sequence, you add back pressure above the first relief valve piston, causing a change in the pressure setting. For example, the estimated relieving pressure of a valve stack could be:

As the relief flow then passes through the second valve, the stack also experiences a change in relieving capacity. If any of these conditions exist, the valve should be replaced.

The condition of the discharge piping should also be inspected. Valves should be piped to ensure that they do not collect dirt and debris. The vent pipes should be protected to prevent the entrance of rain water, which would inhibit valve operation.

Relief valves should be changed out after discharge to ensure safeguarding a system with a properly set relief valve. Most systems are subject to accumulations of piping debris (i.e., metal shavings and solder impurities) as the system is fitted for installation.

These impurities are generally blown into the relief valve seats at the time the valve is discharged. The impinged debris then inhibits the relief valve from reseating at its original set pressure.

Replacement intervals for valves that have not discharged may be dictated by city, state, or federal regulations. In addition, they may also be regulated by industry standards, company policies, insurance requirements, or unwritten, accepted standards of good practice.

In the case of city, state, or federal regulations and insurance regulations, there appear to be no written rules covering the replacement schedule. However, these agencies do govern by verbal requirements requesting that system operators-owners provide proof of the reliability of existing relief valves.

Industry standardsThe International Institute of Ammonia Refrigeration (IIAR), in its Bulletin 109, IIAR Minimum Safety Criteria for a Safe Ammonia Refrigeration System, recommends that the relief valve be replaced or inspected, cleaned, and tested every five years.

ANSI STD K61.1-1989, Safety Requirements for the Storage and Handling of Anhydrous Ammonia, is very specific in its requirements. Paragraph 6.8.15 states:

“No container pressure relief devices shall be used after the replacement date as specified by the manufacturer of the device. If no date is specified, a pressure relief valve shall be replaced no later than five years following the date of its manufacture.”

In industrial refrigeration, the current recommendation is to replace the relief valve on a five-year cycle. Be sure to check with other agencies to verify that a more stringent regulation is not applicable.

Provide a pressure vessel that will permit the relief valve to be set at least 25% above the maximum system pressure. However, the relief valve setting cannot exceed the maximum allowable working pressure as stamped on the vessel the relief valve is protecting.

Use the proper size and length of discharge tube or pipe. Correct sizing is required to prevent back pressure from building up in the discharge line, preventing the relief valve from discharging at its rated capacity.

The use of a three-way valve with two relief devices, which complies with the code requirements for vessels 10 cu ft or more in gross volume, is recommended for any installation containing a large quantity of expensive refrigerant.

When the outlets of two or more relief devices are connected to a common header, the size of the header must be large enough to remain unaffected by back pressure, even if all the relief devices were to discharge simultaneously.

Safety valves and pressure relief valves are crucial for one main reason: safety. This means safety for the plant and equipment as well as safety for plant personnel and the surrounding environment.

Safety valves and pressure relief valves protect vessels, piping systems, and equipment from overpressure, which, if unchecked, can not only damage a system but potentially cause an explosion. Because these valves play such an important role, it’s absolutely essential that the right valve is used every time.

The valve size must correspond to the size of the inlet and discharge piping. The National Board specifies that the both the inlet piping and the discharge piping connected to the valve must be at least as large as the inlet/discharge opening on the valve itself.

The connection types are also important. For example, is the connection male or female? Flanged? All of these factors help determine which valve to use.

The set pressure of the valve must not exceed the maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP) of the boiler or other vessel. What this means is that the valve must open at or below the MAWP of the equipment. In turn, the MAWP of the equipment should be at least 10% greater than the highest expected operating pressure under normal circumstances.

Temperature affects the volume and viscosity of the gas or liquid flowing through the system. Temperature also helps determine the ideal material of construction for the valve. For example, steel valves can handle higher operating temperatures than valves made of either bronze or iron. Both the operating and the relieving temperature must be taken into account.

Back pressure, which may be constant or variable, is pressure on the outlet side of the pressure relief valve as a result of the pressure in the discharge system. It can affect the set pressure of the upstream valve and cause it to pop open repeatedly, which can damage the valve.

For installations with variable back pressure, valves should be selected so that the back pressure doesn’t exceed 10% of the valve set pressure. For installations with high levels of constant back pressure, a bellows-sealed valve or pilot-operated valve may be required.

Different types of service (steam, air, gas, etc.) require different valves. In addition, the valve material of construction needs to be appropriate for the service. For example, valves made of stainless steel are preferable for corrosive media.

Safety valves and relief valves must be able to relieve pressure at a certain capacity. The required capacity is determined by several factors including the geometry of the valve, the temperature of the media, and the relief discharge area.

These are just the basic factors that must be considered when selecting and sizing safety valves and relief valves. You must also consider the physical dimensions of the equipment and the plant, as well as other factors related to the environment in which the valve will operate.

Safety is of the utmost importance when dealing with pressure relief valves. The valve is designed to limit system pressure, and it is critical that they remain in working order to prevent an explosion. Explosions have caused far too much damage in companies over the years, and though pressurized tanks and vessels are equipped with pressure relief vales to enhance safety, they can fail and result in disaster.

That’s also why knowing the correct way to test the valves is important. Ongoing maintenance and periodic testing of pressurized tanks and vessels and their pressure relief valves keeps them in working order and keep employees and their work environments safe. Pressure relief valves must be in good condition in order to automatically lower tank and vessel pressure; working valves open slowly when the pressure gets high enough to exceed the pressure threshold and then closes slowly until the unit reaches the low, safe threshold. To ensure the pressure relief valve is in good working condition, employees must follow best practices for testing them including:

If you consider testing pressure relief valves a maintenance task, you’ll be more likely to carry out regular testing and ensure the safety of your organization and the longevity of your

It’s important to note, however, that the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) and National Board Inspection Code (NBIC), as well as state and local jurisdictions, may set requirements for testing frequency. Companies are responsible for checking with these organizations to become familiar with the testing requirements. Consider the following NBIC recommendations on the frequency for testing relief valves:

High-pressure steam boilers greater than 15 psi and less than 400 psi – perform manual check every six months and pressure test annually to verify nameplate set pressure

High-pressure steam boilers 400 psi and greater – pressure test to verify nameplate set pressure every three years or as determined by operating experience as verified by testing history

High-temperature hot water boilers (greater than 160 psi and/or 250 degrees Fahrenheit) – pressure test annually to verify nameplate set pressure. For safety reasons, removal and testing on a test bench is recommended

When testing the pressure relief valve, raise and lower the test lever several times. The lever will come away from the brass stem and allow hot water to come out of the end of the drainpipe. The water should flow through the pipe, and then you should turn down the pressure to stop the leak, replace the lever, and then increase the pressure.

One of the most common problems you can address with regular testing is the buildup of mineral salt, rust, and corrosion. When buildup occurs, the valve will become non-operational; the result can be an explosion. Regular testing helps you discover these issues sooner so you can combat them and keep your boiler and valve functioning properly. If no water flows through the pipe, or if there is a trickle instead of a rush of water, look for debris that is preventing the valve from seating properly. You may be able to operate the test lever a few times to correct the issue. You will need to replace the valve if this test fails.

When testing relief valves, keep in mind that they have two basic functions. First, they will pop off when the pressure exceeds its safety threshold. The valve will pop off and open to exhaust the excess pressure until the tank’s pressure decreases to reach the set minimum pressure. After this blowdown process occurs, the valve should reset and automatically close. One important testing safety measure is to use a pressure indicator with a full-scale range higher than the pop-off pressure.

Thus, you need to be aware of the pop-off pressure point of whatever tank or vessel you test. You always should remain within the pressure limits of the test stand and ensure the test stand is assembled properly and proof pressure tested. Then, take steps to ensure the escaping pressure from the valve is directed away from the operator and that everyone involved in the test uses safety shields and wears safety eye protection.

After discharge – Because pressure relief valves are designed to open automatically to relieve pressure in your system and then close, they may be able to open and close multiple times during normal operation and testing. However, when a valve opens, debris may get into the valve seat and prevent the valve from closing properly. After discharge, check the valve for leakage. If the leakage exceeds the original settings, you need to repair the valve.

According to local jurisdictional requirements – Regulations are in place for various locations and industries that stipulate how long valves may operate before needing to be repair or replaced. State inspectors may require valves to be disassembled, inspected, repaired, and tested every five years, for instance. If you have smaller valves and applications, you can test the valve by lifting the test lever. However, you should do this approximately once a year. It’s important to note that ASME UG136A Section 3 requires valves to have a minimum of 75% operating pressure versus the set pressure of the valve for hand lifting to be performed for these types of tests.

Depending on their service and application– The service and application of a valve affect its lifespan. Valves used for clean service like steam typically last at least 20 years if they are not operated too close to the set point and are part of a preventive maintenance program. Conversely, valves used for services such as acid service, those that are operated too close to the set point, and those exposed to dirt or debris need to be replaced more often.

Pressure relief valves serve a critical role in protecting organizations and employees from explosions. Knowing how and when to test and repair or replace them is essential.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

The primary purpose of a safety valve is to protect life, property and the environment. Safety valves are designed to open and release excess pressure from vessels or equipment and then close again.

The function of safety valves differs depending on the load or main type of the valve. The main types of safety valves are spring-loaded, weight-loaded and controlled safety valves.

Regardless of the type or load, safety valves are set to a specific set pressure at which the medium is discharged in a controlled manner, thus preventing overpressure of the equipment. In dependence of several parameters such as the contained medium, the set pressure is individual for each safety application.

The Supreme Court has reinforced the theory of the First Amendment as a "safety valve," reasoning that citizens who are free to to express displeasure against government through peaceful protest will be deterred from undertaking violent means. The boundary between what is peaceful and what is violent is not always clear. For example, in this 1965 photo, Alabama State College students participated in a non-violent protest for voter rights when deputies confronted them anyway, breaking up the gathering. (AP Photo/Perry Aycock, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Under the safety valve rationale, citizens are free to make statements concerning controversial societal issues to express their displeasure against government and its policies. In assuming this right, citizens will be deterred from undertaking violent means to draw attention to their causes.

The First Amendment, in safeguarding freedom of speech, religion, peaceable assembly, and a right to petition government, embodies the safety valve theory.

Such a presumption was evident in the Court’s decisions in Near v. Minnesota (1931), which struck down a state’s attempt to close down the scurrilous Saturday Press, and in New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), in which the Court lifted an injunction against publication of the Pentagon Papers.

These and other decisions rest on the idea that it is better to allow members of the public to judge ideas for themselves and act accordingly than to have the government act as a censure. The Court has even shown support in cases concerning obscenity or speech that incites violent action. The safety valve theory suggests that such a policy is more likely to lead to civil peace than to civil disruption.

Instances abound where government has intervened to “restore” order by confronting apparently peaceful protests. For example, in the 1960s during the Civil Rights Movement, police in Montgomery, Alabama, sought to quell a series of nonviolent protests by students at the Alabama State College.

The students, all of whom were black, were affirming their civil rights in a peaceful way but were met with force by the Montgomery police. Another example took place at Kent State University in 1970 when the National Guard fired upon students protesting the Vietnam War.

Justice Louis D. Brandeis recognized the potential for the First Amendment to serve as a safety valve in his concurring opinion in Whitney v. California (1927) when he wrote: “fear breeds repression; . . . repression breeds hate; . . . hate menaces stable government; . . . the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies; and the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.”

This article was originally published in 2009. John Omachonu, Ph.D., is an educator, broadcast media practitioner, and teacher, who for more than two decades, taught college-level courses in mass media law and ethics. He is committed to the tenets, principles and practices of the First Amendment. Send Feedback on this article

8613371530291

8613371530291