justice safety valve act brands

This act would provide sentencing judges with discretion to depart from mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent offenders who meet specified criteria.

(2) Involve any sexual contact offense by the defendant against a minor (other than an offense involving sexual conduct where the victim was at least 13 years old and the offender was not more than four years older than the victim and the sexual conduct was consensual);

(B) The court may depart from the applicable mandatory minimum sentence if the court finds substantial and compelling reasons on the record that, in giving due regard to the nature of the crime, history and character of the defendant and his or her chances of successful rehabilitation that:

(A) Upon departing from mandatory minimum sentences, judges shall report to [the Sentencing Commission or other appropriate agency] which shall, one year following the enactment of this statute and annually thereafter, make available in electronic form and on the World Wide Web, a report as to the number of departures from mandatory minimum sentences made by each judge in the state.

(A) Twenty-five percent of the savings realized as a result of this act shall revert to the general fund to advance evidence-based practices shown to reduce recidivism.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

Congress changed all of that in the First Step Act. In expanding the number of people covered by the safety valve, Congress wrote that a defendant now must only show that he or she “does not have… (A) more than 4 criminal history points… (B) a prior 3-point offense… and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense.”

The “safety valve” was one of the only sensible things to come out of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the bill championed by then-Senator Joe Biden that, a quarter-century later, has been used to brand him a mass-incarcerating racist. The safety valve was intended to let people convicted of drug offenses as first-timers avoid the crushing mandatory minimum sentences that Congress had imposed on just about all drug dealing.

Eric Lopez got caught smuggling meth across the border. Everyone agreed he qualified for the safety valve except for his criminal history. Eric had one prior 3-point offense, and the government argued that was enough to disqualify him. Eric argued that the First Step Actamendment to the “safety valve” meant he had to have all three predicates: more than 4 points, one 3-point prior, and one 2-point prior violent offense.

Last week, the 9th Circuit agreed. In a decision that dramatically expands the reach of the safety valve, the Circuit applied the rules of statutory construction and held that the First Step amendment was unambiguous. “Put another way, we hold that ‘and’ means ‘and.’”

“We recognize that § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language might be viewed as a considerable departure from the prior version of § 3553(f)(1), which barred any defendant from safety-valve relief if he or she had more than one criminal-history point under the Sentencing Guidelines… As a result, § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language could possibly result in more defendants receiving safety-valve relief than some in Congress anticipated… But sometimes Congress uses words that reach further than some members of Congress may have expected… We cannot ignore Congress’s plain and unambiguous language just because a statute might reach further than some in Congress expected… Section 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language, the Senate’s own legislative drafting manual, § 3553(f)(1)’s structure as a conjunctive negative proof, and the canon of consistent usage result in only one plausible reading of § 3553(f)(1)’s“and” here: “And” is conjunctive. If Congress meant § 3553(f)(1)’s “and” to mean “or,” it has the authority to amend the statute accordingly. We do not.”

The weights of the pills vary by type and brand. Pills with less “substance” actually weigh more, because they contain more filler like acetaminophen, or Tylenol.

Author Lauren Krisai, a JMI adjunct scholar and director of criminal justice reform at the Reason Foundation, says it’s time for the Legislature to adopt a “safety valve.”

A safety valve provision would allow judges to exercise discretion when sentencing individuals in cases where Florida’s mandatory sentences don’t fit the crimes.

“Safety valve legislation neither eliminates the underlying mandatory minimum sentencing law, nor does it require judges to sentence offenders below the minimum term. It is a narrowly tailored exception for certain offenders and under certain circumstances,” the brief says.

“There’s no evidence from Florida or elsewhere that shows when judges are allowed to determine sentences —or, to judge —public safety is threatened,” Krisai concluded.

Empire Bulkers Limited and Joanna Maritime Limited, two related companies based in Greece, were sentenced today for committing knowing and willful violations of the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS) and the Ports and Waterways Safety Act related to their role as the operator and owner of the Motor Vessel (M/V) Joanna.

During the same inspection, the Coast Guard also discovered an unreported safety hazard. Following a trail of oil drops, inspectors found an active fuel oil leak in the engine room where the pressure relief valves on the fuel oil heaters, a critical safety device necessary to prevent explosion, had been disabled. In pleading guilty, the defendants admitted that the plugging of the relief valves in the fuel oil purifier room and the large volume of oil leaking from the pressure relief valve presented hazardous conditions that had not been immediately reported to the Coast Guard in violation of the Ports and Waterways Safety Act. Had there been a fire or explosion in the purifier room, it could have been catastrophic and resulted in a loss of propulsion, loss of life, and pollution, according to a joint factual statement filed in court.

“Make no mistake, willful tampering with required pollution control equipment and falsifying official ship logs to conceal illegal discharges are serious criminal offenses,” said Assistant Attorney General Todd Kim of the Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division. “In concealing major safety problems from the Coast Guard, the defendants here not only violated the law, but also recklessly risked the lives of the crew and the environment.”

“This ship owner and manager operated their foreign flagged vessel in U.S. waters in deliberate violation of the environmental and safety laws designed to protects our ports and waters,” said U.S. Attorney Duane A. Evans for the Eastern District of Louisiana. “Illegal, deceitful and dangerous conduct will not be tolerated and will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.”

Solutions: Shift funding from local or state public safety budgets into a local grant program to support community-led safety strategies in communities most impacted by mass incarceration, over-policing, and crime. States can use Colorado’s “Community Reinvestment” model. In fiscal year 2021-22 alone, four Community Reinvestment Initiatives will provide $12.8 million to community-based services in reentry, harm reduction, crime prevention, and crime survivors.

More information: See details about the CAHOOTS program. For a review of other strategies ranging from police-based responses to community-based responses, see the Vera Institute of Justice’s Behavioral Health Crisis Alternatives, the Brookings Institute’s Innovative solutions to address the mental health crisis, and The Council of State Governments’ Expanding First Response: A Toolkit for Community Responder Programs.

Reclassify criminal offenses and turn misdemeanor charges that don’t threaten public safety into non-jailable infractions, or decriminalize them entirely.

Problem:While the Supreme Court has affirmed that until someone is an adult, they cannot be held fully culpable for crimes they have committed, in every state youth under 18 can be tried and sentenced in adult criminal courts and, as of 2019, there was no minimum age in at least 21 states and D.C. The juvenile justice system can also be shockingly punitive: In most states, even young children can be punished by the state, including for “status offenses” that aren’t law violations for adults, such as running away.

More information:For information on the youth justice reforms discussed, see The National Conference of State Legislatures Juvenile Age of Jurisdiction and Transfer to Adult Court Laws; the recently-closed Campaign for Youth Justice resources summarizing legislative reforms to Raise the Age, limit youth transfers, and remove youth from adult jails (available here and here); Youth First Initiative’s No Kids in Prison campaign; and The Vera Institute of Justice’s Status Offense Toolkit.

Legislation: Tennessee SB 0985/ HB 1449 (2019) and Massachusetts S 2371 (2018) permit or require primary caregiver status and available alternatives to incarceration to be considered for certain defendants prior to sentencing. New Jersey A 3979 (2018) requires incarcerated parents be placed as close to their minor child’s place of residence as possible, allows contact visits, prohibits restrictions on the number of minor children allowed to visit an incarcerated parent, and also requires visitation be available at least 6 days a week.

More information:See Families for Justice as Healing, Free Hearts, Operation Restoration, and Human Impact Partners’ Keeping Kids and Parents Together: A Healthier Approach to Sentencing in MA, TN, LA and the Illinois Task Force on Children of Incarcerated Parents’ Final Report and Recommendations.

Legislation: Illinois Pretrial Fairness Act, HB 3653 (2019), passed in 2021, abolishes money bail, limits pretrial detention, regulates the use of risk assessment tools in pretrial decisions, and requires reconsideration of pretrial conditions or detention at each court date. When this legislation takes effect in 2023, roughly 80% of people arrested in Cook County (Chicago) will be ineligible for pretrial detention.

More information: See The Bail Project’s After Cash Bail, the Pretrial Justice Institute’s website, the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School’s Moving Beyond Money, and Critical Resistance & Community Justice Exchange’s On the Road to Freedom. For information on how the bail industry — which often actively opposes efforts to reform the money bail system — profits off the current system, see our report All profit, no risk: How the bail industry exploits the legal system.

Problem: Proposals and pushes to build new carceral buildings and enlarge existing ones, particularly jails, are constantly being advanced across the U.S. These proposals typically seek to increase the capacity of a county or state to incarcerate more people, and have frequently been made even when criminal justice reforms have passed — but not yet been fully implemented — which are intended to reduce incarceration rates, or when there are numerous measures that can and should be adopted to reduce the number of people held behind bars.

Solutions: States should pass legislation establishing moratoriums on jail and prison construction. Moratoriums on building new, or expanding existing, facilities allow reforms to reduce incarceration to be prioritized over proposals that would worsen our nation’s mass incarceration epidemic. Moratoriums also allow for the impact of reforms enacted to be fully realized and push states to identify effective alternatives to incarceration.

Solutions: State legislative strategies include: enacting presumptive parole, second-look sentencing, and other common-sense reforms, such as expanding “good time” credit policies. All of these changes should be made retroactive, and should not categorically exclude any groups based on offense type, sentence length, age, or any other factor.

Legislation: Federally, S 2146 (2019), the Second Look Act of 2019, proposed to allow people to petition a federal court for a sentence reduction after serving at least 10 years. California AB 2942 (2018) removed the Parole Board’s exclusive authority to revisit excessive sentences and established a process for people serving a sentence of 15 years-to-life to ask the district attorney to make a recommendation to the court for a new sentence after completing half of their sentence or 15 years, whichever comes first. California AB 1245 (2021) proposed to amend this process by allowing a person who has served at least 15 years of their sentence to directly petition the court for resentencing. The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers has created model legislation that would allow a lengthy sentence to be revisited after 10 years.

More information: For a discussion of reasons and strategies for reducing excessive sentences, see our reports Eight Keys to Mercy: How to shorten excessive prison sentences and Reforms Without Results: Why states should stop excluding violent offenses from criminal justice reforms. For materials on second-look sentencing, including a catalogue of legislation that has been introduced in states, see Families Against Mandatory Minimums’ Second Look Sentencing page.

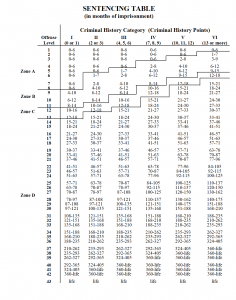

Problem: Automatic sentencing structures have fueled the country’s skyrocketing incarceration rates. For example, mandatory minimum sentences, which by the 1980s had been enacted in all 50 states, reallocate power from judges to prosecutors and force defendants into plea bargains, exacerbate racial disparities in the criminal legal system, and prevent judges from taking into account the circumstances surrounding a criminal charge. In addition, “sentencing enhancements,” like those enhanced penalties that are automatically applied in most states when drug crimes are committed within a certain distance of schools, have been shown to exacerbate racial disparities in the criminal legal system. Both mandatory minimums and sentencing enhancements harm individuals and undermine our communities and national well-being, all without significant increases to public safety.

Solutions: The best course is to repeal automatic sentencing structures so that judges can craft sentences to fit the unique circumstances of each crime and individual. Where that option is not possible, states should: adopt sentencing “safety valve” laws, which give judges the ability to deviate from the mandatory minimum under specified circumstances; make enhancement penalties subject to judicial discretion, rather than mandatory; and reduce the size of sentencing enhancement zones.

Legislation: Several examples of state and federal statutes are included in Families Against Mandatory Minimums’ (FAMM) Turning Off the Spigot. The American Legislative Exchange Council has produced model legislation, the Justice Safety Valve Act.

Problem: The release of individuals who have been granted parole is often delayed for months because the parole board requires them to complete a class or program (often a drug or alcohol treatment program) that is not readily available before they can go home. As of 2015, at least 40 states used institutional program participation as a factor in parole determinations. In some states — notably Tennessee and Texas — thousands of people whom the parole board deemed “safe” to return to the community remain incarcerated simply because the state has imposed this bureaucratic hurdle.

Solutions: States should increase the dollar amount of a theft to qualify for felony punishment, and require that the threshold be adjusted regularly to account for inflation. This change should also be made retroactive for all people currently in prison, on parole, or on probation for felony theft.

More information: For the felony threshold in your state and the date it was last updated, see our explainer How inflation makes your state’s criminal justice system harsher today than it was yesterday. The Pew Charitable Trusts report States Can Safely Raise Their Felony Theft Thresholds, Research Shows demonstrates that in the states that have recently increased the limits, this did not increase the risk of offending nor did it lead to more expensive items being stolen.

Problem: Probation and parole are supposed to provide alternatives to incarceration. However, the conditions of probation and parole are often unrelated to the individual’s crime of conviction or their specific needs, and instead set them up to fail. For example, restrictions on associating with others and requirements to notify probation or parole officers before a change in address or employment have little to do with either public safety or “rehabilitation.” Additionally, some states allow community supervision to be revoked when a person is “alleged” to have violated — or believed to be “about to” violate — these or other terms of their supervision. Adding to the problem are excessively long supervision sentences, which spread resources thin and put defendants at risk of lengthy incarceration for subsequent minor offenses or violations of supervision rules. Because probation is billed as an alternative to incarceration and is often imposed through plea bargains, the lengths of probation sentences do not receive as much scrutiny as they should.

Solutions: States should limit incarceration as a response to supervision violations to when the violation has resulted in a new criminal conviction and poses a direct threat to public safety. If incarceration is used to respond to technical violations, the length of time served should be limited and proportionate to the harm caused by the non-criminal rule violation.

More information: Challenging E-Carceration, provides details about the encroachment of electronic monitoring into community supervision, and Cages Without Bars provides details about electronic monitoring practices across a number of U.S. jurisdictions and recommendations for reform. Fact sheets, case studies, and guidelines for respecting the rights of people on electronic monitors are available from the Center for Media Justice.

Solutions: Stop suspending, revoking, and prohibiting the renewal of driver’s licenses for nonpayment of fines and fees. Since 2017, fifteen states (Calif., Colo., Hawaii, Idaho, Ill., Ky., Minn., Miss., Mont., Nev., Ore., Utah, Va., W.Va., and Wyo.) and the District of Columbia have eliminated all of these practices.

Legislation: California AB 1869 (2020) eliminated the ability to enforce and collect probation fees. Prior to passage of this legislation, multiple counties had passed ordinances to address probation fees. For example, San Francisco County Ordinance No. 131-18 (2018) eliminated all discretionary criminal justice fees, including probation fees; the ordinance includes a detailed discussion of the County’s reasons for ending these fees. Louisiana HB 249 (2017) requires inquiries be made into a person’s ability to pay before imposing fines and fees or enforcing any penalties for failure to pay.

More information: See our briefing with national data and state-specific data for 15 states (Colo., Idaho, Ill., La., Maine, Mass., Mich., Miss., Mont., N.M., N.D., Ohio, Okla., S.C., and Wash.) that charge monthly fees even though half (or more) of their probation populations earn less than $20,000 per year. States with privatized misdemeanor probation systems will find helpful the six recommendations on pages 7-10 of the Human Rights Watch report Set up to Fail: The Impact of Offender-Funded Private Probation on the Poor.

Problem: Calls home from prisons and jails cost too much because the prison and jail telephone industry offers correctional facilities hefty kickbacks in exchange for exclusive contracts. While most state prison phone systems have lowered their rates, and the Federal Communications Commission has capped the interstate calling rate for small jails at 21c per minute, many jails are charging higher prices for in-state calls to landlines.

Legislation and regulations: Legislation like Connecticut’s S.B. 972 (2021) ensured that the state — not incarcerated people — pay for the cost of calls. Short of that, the best model is New York Corrections Law S 623 which requires that contracts be negotiated on the basis of the lowest possible cost to consumers and bars the state from receiving any portion of the revenue. (While this law only applied to contracts with state prisons, an ideal solution would also include local jail contracts.) States can also increase the authority of public utilities commissions to regulate the industry (as Colorado did) and California Public Utilities Commission has produced the strongest and most up-to-date state regulations of the industry.

More information: For more reform ideas, including data on the highest rate charged in each state, see our forthcoming report State of Phone Justice. For additional information, see our Regulating the prison phone industry page and the work of our ally Worth Rises.

Solutions: States have the power to decisively end this pernicious practice by prohibiting facilities from using release cards that charge fees, and requiring fee-free alternative payment methods.

Problem: Despite a growing body of evidence that medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is effective at treating opioid use disorders, most prisons are refusing to offer those treatments to incarcerated people, exacerbating the overdose and recidivism rate among people released from custody. In fact, studies have stated that drug overdose is the leading cause of death after release from prison, and the risk of death is significantly higher for women.

Problem: Most states bar some or all people with felony convictions from voting. However, the laws across states vary: Only 2 states (Maine and Vermont) and 2 territories (D.C. and Puerto Rico) never deprive people of their right to vote based on a criminal conviction, while over 20% of states have laws providing for permanent disenfranchisement for at least some people with criminal convictions. Additionally, while approximately 40% of states limit the right to vote only when a person is incarcerated, others require a person to complete probation or parole before their voting rights are restored, or institute waiting periods for people who have completed or are on probation or parole. In at least 6 states, people who have been convicted of a misdemeanor lose their right to vote while they are incarcerated. Given the racial disparities in the criminal justice system, these policies disproportionately exclude Black and Latinx Americans from the ballot box. As of 2022, 1 in 19 Black adults nationwide was disenfranchised because of a felony conviction (and in 8 states, it’s more than 1 in 8).

Solutions: Change state laws and/or state constitutions to remove disenfranchising provisions. Additionally, governors should immediately restore voting rights to disenfranchised people via executive action when they have the power to do so.

Legislation: D.C. B 23-0324 (2019) ended the practice of felony disenfranchisement for Washington D.C. residents; Hawai’i SB 1503/HB 1506 (2019) would have allowed people who were Hawai’i residents prior to incarceration to vote absentee in Hawai’i elections; New Jersey A 3456/S 2100 (2018) would have ended the practice of denying New Jersey residents incarcerated for a felony conviction of their right to vote.

Problem: Many people who are detained pretrial or jailed on misdemeanor convictions maintain their right to vote, but many eligible, incarcerated people are unaware that they can vote from jail. In addition, state laws and practices can make it impossible for eligible voters who are incarcerated to exercise their right to vote, by limiting access to absentee ballots, when requests for ballots can be submitted, how requests for ballots and ballots themselves must be submitted, and how errors on an absentee ballot envelope can be fixed.

Problem: The Census Bureau’s practice of tabulating incarcerated people at correctional facility locations (rather than at their home addresses) leads state and local governments to draw skewed electoral districts that grant undue political clout to people who live near large prisons and dilute the representation of people everywhere else.

Solutions: States can pass legislation to count incarcerated people at home for redistricting purposes, as Calif., Colo., Conn., Del., Ill., Md., Nev., N.J., N.Y, Va., and Wash. have done. Ideally, the Census Bureau would implement a national solution by tabulating incarcerated people at home in the 2030 Census, but states must be prepared to fix their own redistricting data should the Census fail to act. Taking action now ensures that your state will have the data it needs to end prison gerrymandering in the 2030 redistricting cycle.

Problem: In courthouses throughout the country, defendants are routinely denied the promise of a “jury of their peers,” thanks to a lack of racial diversity in jury boxes. One major reason for this lack of diversity is the constellation of laws prohibiting people convicted (or sometimes simply accused) of crimes from serving on juries. These laws bar more than twenty million people from jury service, reduce jury diversity by disproportionately excluding Black and Latinx people, and actually cause juries to deliberate less effectively. Such exclusionary practices often ban people from jury service forever.

Problem: The impacts of incarceration extend far beyond the time that a person is released from prison or jail. A conviction history can act as a barrier to employment, education, housing, public benefits, and much more. Additionally, the increasing use of background checks in recent years, as well as the ability to find information about a person’s conviction history from a simple internet search, allows for unchecked discrimination against people who were formerly incarcerated. The stigma of having a conviction history prevents individuals from being able to successfully support themselves, impacts families whose loved ones were incarcerated, and can result in higher recidivism rates.

More information: See Ending Legal Bias Against Formerly Incarcerated People: Establishing Protected Legal Status, by the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society (now the Othering & Belonging Institute), and Barred Business’s The Protected Campaign for information about the campaign to pass Ordinance 22-O-1748 in Atlanta. For information about unemployment among formerly incarcerated people, see our publications Out of Prison & Out of Work and New data on formerly incarcerated people’s employment reveal labor market injustices.

Ensure that people have access to health care benefits prior to release. Screen and help people enroll in Medicaid benefits upon incarceration and prior to release; if a person’s Medicaid benefits were suspended upon incarceration, ensure that they are active prior to release; and ensure people have their medical cards upon release.

More information: See the Institute for Justice’s End Civil Asset Forfeiture page, the Center for American Progress report Forfeiting the American Dream, and the Drug Policy Alliance’s work on Asset Forfeiture Reform.

Problem: Four states have failed to repeal another outdated relic from the war on drugs — automatic driver’s license suspensions for all drug offenses, including those unrelated to driving. Our analysis shows that there are over 49,000 licenses suspended every year for non-driving drug convictions. These suspensions disproportionately impact low-income communities and waste government resources and time.

Whereas the Parliament of Canada recognizes the objective of protecting the public by addressing dangers to human health or safety that are posed by consumer products;

Whereas the Parliament of Canada recognizes that along with the Government of Canada, individuals and suppliers of consumer products have an important role to play in addressing dangers to human health or safety that are posed by consumer products;

Whereas the Parliament of Canada recognizes that, given the impact activities with respect to consumer products may have on the environment, there is a need to create a regulatory system regarding consumer products that is complementary to the regulatory system regarding the environment;

And whereas the Parliament of Canada recognizes that the application of effective measures to encourage compliance with the federal regulatory system for consumer products is key to addressing the dangers to human health or safety posed by those products;

advertisementadvertisement includes a representation by any means for the purpose of promoting directly or indirectly the sale of a consumer product. (publicité)analystanalyst means an individual designated as an analyst under section 29 or under section 28 of the analyste)article to which this Act or the regulations applyarticle to which this Act or the regulations apply means(a) a consumer product;

(b) anything used in the manufacturing, importation, packaging, storing, advertising, selling, labelling, testing or transportation of a consumer product; or

(c) a document that is related to any of those activities or a consumer product. (article visé par la présente loi ou les règlements)confidential business informationconfidential business information — in respect of a person to whose business or affairs the information relates — means business information(a) that is not publicly available;

(c) that has actual or potential economic value to the person or their competitors because it is not publicly available and its disclosure would result in a material financial loss to the person or a material financial gain to their competitors. (renseignements commerciaux confidentiels)consumer productconsumer product means a product, including its components, parts or accessories, that may reasonably be expected to be obtained by an individual to be used for non-commercial purposes, including for domestic, recreational and sports purposes, and includes its packaging. (produit de consommation)danger to human health or safetydanger to human health or safety means any unreasonable hazard — existing or potential — that is posed by a consumer product during or as a result of its normal or foreseeable use and that may reasonably be expected to cause the death of an individual exposed to it or have an adverse effect on that individual’s health — including an injury — whether or not the death or adverse effect occurs immediately after the exposure to the hazard, and includes any exposure to a consumer product that may reasonably be expected to have a chronic adverse effect on human health. (danger pour la santé ou la sécurité humaines)documentdocument means anything on which information that is capable of being understood by a person, or read by a computer or other device, is recorded or marked. (document)governmentgovernment means any of the following or their institutions:(a) the federal government;

(f) an international organization of states. (administration)importimport means to import into Canada. (importer)inspectorinspector means an individual designated as an inspector under subsection 19(2). (inspecteur)manufacturemanufacture includes produce, formulate, repackage and prepare, as well as recondition for sale. (fabrication)MinisterMinister means the Minister of Health. (ministre)personperson means an individual or an organization as defined in section 2 of the personne)personal informationpersonal information has the same meaning as in section 3 of the renseignements personnels)prescribedprescribed means prescribed by regulation. (Version anglaise seulement)review officerreview officer means an individual designated as a review officer under section 34. (réviseur)sellsell includes offer for sale, expose for sale or have in possession for sale — or distribute to one or more persons, whether or not the distribution is made for consideration — and includes lease, offer for lease, expose for lease or have in possession for lease. (vente)storingstoring does not include the storing of a consumer product by an individual for their personal use. (entreposage)

(b) is the subject of a recall order made under section 31 or such an order that is reviewed under section 35 or is the subject of a voluntary recall in Canada because the product is a danger to human health or safety; or

(c) is the subject of a measure that the manufacturer or importer has not carried out but is required to carry out under an order made under section 32 or such an order that is reviewed under section 35.

(b) is the subject of a recall order made under section 31 or such an order that is reviewed under section 35 or is the subject of a voluntary recall in Canada because the product is a danger to human health or safety; or

(a) in a manner — including one that is false, misleading or deceptive — that may reasonably be expected to create an erroneous impression regarding the fact that it is not a danger to human health or safety; or

(b) in a manner that is false, misleading or deceptive regarding its certification related to its safety or its compliance with a safety standard or the regulations.

(a) conduct tests or studies on the product in order to obtain the information that the Minister considers necessary to verify compliance or prevent non-compliance with this Act or the regulations;

(b) compile any information that the Minister considers necessary to verify compliance or prevent non-compliance with this Act or the regulations; and

Marginal note:Requirement(1) Any person who manufactures, imports, advertises, sells or tests a consumer product for commercial purposes shall prepare and maintain(a) documents that indicate(i) in the case of a retailer, the name and address of the person from whom they obtained the product and the location where and the period during which they sold the product, and

(4) The Minister may, subject to any terms and conditions that he or she may specify, exempt a person from the requirement to keep documents in Canada if the Minister considers it unnecessary or impractical for the person to keep them in Canada.

(b) a defect or characteristic that may reasonably be expected to result in an individual’s death or in serious adverse effects on their health, including a serious injury;

(2) A person who manufactures, imports or sells a consumer product for commercial purposes shall provide the Minister and, if applicable, the person from whom they received the consumer product with all the information in their control regarding any incident related to the product within two days after the day on which they become aware of the incident.

(3) The manufacturer of the consumer product, or if the manufacturer carries on business outside Canada, the importer, shall provide the Minister with a written report — containing information about the incident, the product involved in the incident, any products that they manufacture or import, as the case may be, that to their knowledge could be involved in a similar incident and any measures they propose be taken with respect to those products — within 10 days after the day on which they become aware of the incident or within the period that the Minister specifies by written notice.

Marginal note:Personal information(1) The Minister may disclose personal information to a person or a government that carries out functions relating to the protection of human health or safety without the consent of the individual to whom the personal information relates if the disclosure is necessary to identify or address a serious danger to human health or safety.

Marginal note:Confidential business information — serious and imminent danger(1) The Minister may, without the consent of the person to whose business or affairs the information relates and without notifying that person beforehand, disclose confidential business information about a consumer product that is a serious and imminent danger to human health or safety or the environment, if the disclosure of the information is essential to address the danger.

Marginal note:Number of inspectors(1) The Minister shall decide on the number of inspectors sufficient for the purpose of the administration and enforcement of this Act and the regulations.

(2) For the purposes of the administration and enforcement of the provisions of this Act and the regulations, the Minister may designate individuals or classes of individuals as inspectors to exercise powers or perform duties or functions in relation to any matter referred to in the designation.

Marginal note:Authority to enter place(1) Subject to subsection 22(1), an inspector may, for the purpose of verifying compliance or preventing non-compliance with this Act or the regulations, at any reasonable time enter a place, including a conveyance, in which they have reasonable grounds to believe that a consumer product is manufactured, imported, packaged, stored, advertised, sold, labelled, tested or transported, or a document relating to the administration of this Act or the regulations is located.

(2) The inspector may, for the purpose referred to in subsection (1),(a) examine or test anything — and take samples free of charge of an article to which this Act or the regulations apply — that is found in the place;

(e) order the owner or person having possession, care or control of an article to which this Act or the regulations apply that is found in the place — or of the conveyance — to move it or, for any time that may be necessary, not to move it or to restrict its movement;

(i) order the owner or person in charge of the place or a person who manufactures, imports, packages, stores, advertises, sells, labels, tests or transports a consumer product at the place to establish their identity to the inspector’s satisfaction or to stop or start the activity.

(2) A justice of the peace may, on ex parte application, issue a warrant authorizing, subject to the conditions specified in the warrant, the person who is named in it to enter a dwelling-house if the justice of the peace is satisfied by information on oath that(a) the dwelling-house is a place described in subsection 21(1);

(4) If an inspector believes that it would not be practical to appear personally to make an application for a warrant under subsection (2), a warrant may be issued by telephone or other means of telecommunication on application submitted by telephone or other means of telecommunication and section 487.1 of the

Marginal note:Forfeiture — conviction for offence(1) If a person is convicted of an offence under this Act, the court may order that a seized thing by means of or in relation to which the offence was committed be forfeited to Her Majesty in right of Canada.

Marginal note:Unlawful imports(1) An inspector who has reasonable grounds to believe that an imported consumer product does not meet the requirements of the regulations or was imported in contravention of a provision of this Act or the regulations may decide whether to give the owner or importer, or the person having possession, care or control of the product, the opportunity to take a measure in respect of it.

(2) In making a decision under subsection (1), the inspector shall consider, among other factors(a) whether the consumer product is a danger to human health or safety; and

(3) If the inspector decides under subsection (1) not to give the owner, importer or the person having possession, care or control of the consumer product the opportunity to take a measure in respect of it, the inspector shall exercise, in respect of the product, any of the powers conferred by the provisions of this Act, other than this section, or of the regulations.

Marginal note:Recall(1) If the Minister believes on reasonable grounds that a consumer product is a danger to human health or safety, he or she may order a person who manufactures, imports or sells the product for commercial purposes to recall it.

Marginal note:Taking measures(1) The Minister may order a person who manufactures, imports, advertises or sells a consumer product to take any measure referred to in subsection (2) if(a) that person does not comply with an order made under section 12 with respect to the product;

(c) the Minister believes on reasonable grounds that the product is the subject of a measure or recall undertaken voluntarily by the manufacturer or importer; or

(2) The measures include(a) stopping the manufacturing, importation, packaging, storing, advertising, selling, labelling, testing or transportation of the consumer product or causing any of those activities to be stopped; and

(b) any measure that the Minister considers necessary to remedy a non-compliance with this Act or the regulations, including any measure that relates to the product that the Minister considers necessary in order for the product to meet the requirements of the regulations or to address or prevent a danger to human health or safety that the product poses.

Marginal note:Request for review(1) Subject to any other provision of this section, an order that is made under section 31 or 32 shall be reviewed on the written request of the person who was ordered to recall a consumer product or to take another measure — but only on grounds that involve questions of fact alone or questions of mixed law and fact — by a review officer other than the individual who made the order.

(2) The written request must state the grounds for review and set out the evidence — including evidence that was not considered by the individual who made the order — that supports those grounds and the decision that is sought. It shall be provided to the Minister within seven days after the day on which the order was provided or, in the event of a serious and imminent danger to human health or safety, any shorter period that may be specified in the order.

Marginal note:Court(1) If, on the application of the Minister, it appears to a court of competent jurisdiction that a person has done or is about to do or is likely to do an act or thing that constitutes or is directed toward the commission of an offence under this Act, the court may issue an injunction ordering the person who is named in the application to(a) refrain from doing an act or thing that it appears to the court may constitute or be directed toward the commission of an offence under this Act; or

Marginal note:Recovery(1) Her Majesty in right of Canada may recover, as a debt due to Her Majesty in right of Canada, any costs incurred by Her Majesty in right of Canada in relation to anything required or authorized under the provisions of this Act, except section 64, or the regulations, including(a) the storage, movement or disposal of a thing; or

Marginal note:Governor in Council(1) The Governor in Council may make regulations for carrying out the purposes and provisions of this Act, including regulations(a) exempting, with or without conditions, a consumer product or class of consumer products from the application of this Act or the regulations or a provision of this Act or the regulations, including exempting consumer products manufactured in Canada for the purpose of export or imported solely for the purpose of export;

(b) exempting, with or without conditions, a class of persons from the application of this Act or the regulations or a provision of this Act or the regulations in relation to a consumer product or class of consumer products;

(f) respecting the manufacturing, importation, packaging, storing, sale, advertising, labelling, testing or transportation of a consumer product or class of consumer products;

(g) prohibiting the manufacturing, importation, packaging, storing, sale, advertising, labelling, testing or transportation of a consumer product or class of consumer products;

(h) respecting the communication of warnings or other health or safety information to the public by a person who manufactures, imports, advertises or sells a consumer product or class of consumer products, including by way of a product’s label or instructions;

(2) A regulation made under this Act may incorporate by reference documents produced by a person or body other than the Minister including by(a) an organization established for the purpose of writing standards, including an organization accredited by the Standards Council of Canada;

(3) A regulation made under this Act may incorporate by reference documents that the Minister reproduces or translates from documents produced by a body or person other than the Minister(a) with any adaptations of form and reference that will facilitate their incorporation into the regulation; or

(4) A regulation made under this Act may incorporate by reference documents that the Minister produces jointly with another government for the purpose of harmonizing the regulation with other laws.

(5) A regulation made under this Act may incorporate by reference technical or explanatory documents that the Minister produces, including(a) specifications, classifications, illustrations, graphs or other information of a technical nature; and

Marginal note:Regulations(1) The Minister may make an interim order that contains any provision that may be contained in a regulation made under this Act if he or she believes that immediate action is required to deal with a significant danger — direct or indirect — to human health or safety.

(4) For the purpose of any provision of this Act other than this section, any reference to regulations made under this Act is deemed to include interim orders, and any reference to a regulation made under a specified provision of this Act is deemed to include a reference to the portion of an interim order containing any provision that may be contained in a regulation made under the specified provision.

Marginal note:Offence(1) A person who contravenes a provision of this Act, other than section 8, 10, 11 or 20, a provision of the regulations or an order made under this Act is guilty of an offence and is liable(a) on conviction on indictment, to a fine of not more than $5,000,000 or to imprisonment for a term of not more than two years or to both; or

(3) A person who contravenes section 8, 10, 11 or 20 or who knowingly or recklessly contravenes another provision of this Act, a provision of the regulations or an order made under this Act is guilty of an offence and is liable(a) on conviction on indictment, to a fine in an amount that is at the discretion of the court or to imprisonment for a term of not more than five years or to both; or

Marginal note:Admissibility of evidence(1) In proceedings for an offence under this Act, a declaration, certificate, report or other document of the Minister or an inspector, analyst or review officer purporting to have been signed by that person is admissible in evidence without proof of the signature or official character of the person appearing to have signed it and, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, is proof of the matters asserted in it.

(2) In proceedings for an offence under this Act, a copy of or an extract from any document that is made by the Minister or an inspector, analyst or review officer that appears to have been certified under the signature of that person as a true copy or extract is admissible in evidence without proof of the signature or official character of the person appearing to have signed it and, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, has the same probative force as the original would have if it were proved in the ordinary way.

(e) subject to the regulations, sets out a lesser amount that may be paid as complete satisfaction of the penalty if paid in the prescribed time and manner.

(2) A notice of violation must clearly summarize, in plain language, the rights and obligations under this section and sections 53 to 66 of the person named in it, including the right to have the acts or omissions that constitute the alleged violation or the amount of the penalty reviewed and the procedure for requesting that review.

Marginal note:Compliance agreements(1) After considering a request under paragraph 53(2)(a), the Minister may enter into a compliance agreement, as described in that paragraph, with the person making the request on any terms and conditions that are satisfactory to the Minister, which terms and conditions may(a) include a provision for the giving of reasonable security, in a form and in an amount satisfactory to the Minister, as a guarantee that the person will comply with the compliance agreement; and

(6) If a person pays the amount set out in a notice of default under subsection (4) in the prescribed time and manner,(a) the Minister shall accept the amount as complete satisfaction of the amount owing; and

Marginal note:Review — with respect to facts(1) On completion of a review requested under paragraph 53(2)(b) with respect to the acts or omissions that constitute the alleged violation, the Minister shall determine whether the person requesting the review committed the violation. If the Minister determines that the person committed the violation but that the amount of the penalty was not established in accordance with the regulations, the Minister shall correct the amount and cause a notice of any decision under this subsection to be provided to the person who requested the review.

(2) Every rule and principle of the common law that renders any circumstance a justification or excuse in relation to a charge for an offence under this Act applies in respect of a violation to the extent that it is not inconsistent with this Act.

Marginal note:Committee(1) The Minister shall establish a committee to provide him or her with advice on matters in connection with the administration of this Act, including the labelling of consumer products.

Disposable metal containers that contain a pressurizing fluid composed in whole or in part of vinyl chloride and that are designed to release pressurized contents by the use of a manually operated valve that forms an integral part of the container.

The movement for criminal justice reform is permeating every corner of our lives. From prime-time discussions on major cable news channels to frequent mentions on local news stations, from Facebook timelines to dinner table discussions, the words “justice reform” have become familiar with individuals, students, families and communities across the country.

This popularization of justice reform is largely a result of its grand entrance to the national stage by the successful passage of the First Step Act. Directly associated with the push for the First Step Act were the both heartbreaking and inspiring stories of Alice Marie Johnson and Matthew Charles. These two stories alone quite literally changed hearts and minds on the way we approach incarceration in our country. Within a matter of months, Alice and Matthew found themselves both newly freed Americans and guests of President Donald Trump at his 2019 State of the Union Address, no less.

The left and the right, in an environment of intense political discord, have finally found something special in the issue of criminal justice reform. An issue to champion and make progress on in a productive, meaningful, agreeable and truly bipartisan way. With a long-standing seal of approval from most Democrats and a recent seal of approval from high-profile Republicans (including our very adamantly law-and-order president), safely reducing our overincarceration problem has become a political winner. This is icing on the cake, though, as implementing such reforms have much more powerful and humane impacts that far transcend political calculations.

All of this is to say that criminal justice reform is far from being a one-and-done deal, but thanks to its popularity, the movement is continuing. The First Step Act was just that — a first step. For the federal system, and for other prison systems across our country, there is much work to be done to ensure that our justice system is in fact rehabilitating its incarcerated population, which totals around 2.2 million nationwide.

The dozens of states that had implemented some type of justice reform before the First Step Act have now had their work validated by Congress and can continue their efforts to smartly reduce incarceration and crime. And for states that have not, the light is bright green. Reforming their justice systems should now be a cakewalk.

We have seen a swell in favor of criminal justice reform across some states already, as red and blue states alike realize that they need to follow in the footsteps of the federal government and get on board with the popularity of criminal justice reform.

In North Carolina and Florida, for example, state legislators championed support for their own “First Step” bills, to implement similar reforms from the federal First Step Act in their state justice systems, such as a safety valve. Some states, like Ohio and Mississippi, have seen pushes to reform certain sentencing laws and procedures for drug offenses. Others like Utah, Kentucky, Minnesota, Oklahoma and Pennsylvania have capitalized on the widespread support for second chances, engaging on expungement and record sealing, probation and parole reform, and occupational licensing reform.

In states like Mississippi, Kentucky, Utah, and Oklahoma, these movements have been successful. And others have significant momentum behind them, such as Ohio, whose House Judiciary Committee recently heard testimony on their “Next Step Ohio” Act. In other states, however, like Florida, bills that would have been tremendous for reform unfortunately died in the legislative process.

To these states that lost out on the opportunity to reform their justice systems this year, the message should be clear: Try again, as soon as possible, and as boldly as possible. There is no danger for fallout — politically or otherwise — from supporting smart-on-crime justice reform efforts. The states that have done this know this, and fortunately are continuing to make headway into reforms that reduce prison populations, crime rates, and spending, all while increasing the value that returning citizens have in our communities.

The states that are lagging behind, however, must take a page out of the book both of other states that have seen the positive impacts of justice reform and of the federal government, whose champions of the First Step Act have been praised from all directions on their work on this issue. If there is one thing to be certain of, it is that smartly done criminal justice reform is a win-win, helping all and hurting none.

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Today, Senator Rand Paul (R-KY), Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) reintroduced the Justice Safety Valve Act, S. 1127, in the U.S. Senate. Representative Bobby Scott (D-VA) and Representative Thomas Massie (R-KY) are reintroducing companion legislation in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Last week, Attorney General Jeff Sessions directed federal prosecutors to pursue the most serious charges and maximum sentences in their cases, returning to stricter enforcement of mandatory minimum sentences. The Justice Safety Valve Act would give federal judges the ability to impose sentences below mandatory minimums in appropriate cases based on mitigating factors.

“When we require that judges sentence offenders to years, sometimes decades, longer than is needed to keep our communities safe, it comes at extraordinary costs. An outgrowth of the failed War on Drugs, mandatory sentencing strips critical public safety resources away from law enforcement strategies that actually make our communities safer. It also comes with a human cost, particularly for communities of color, and results in a criminal justice system that is anything but ‘just.’ Our bipartisan approach offers a simple solution: Let judges judge,” said Sen. Leahy.

"Attorney General Sessions" directive to all federal prosecutors to charge the most serious offenses, including mandatory minimums, ignores the fact that mandatory minimum sentences have been studied extensively and have been found to distort rational sentencing systems, discriminate against minorities, waste money, and often require a judge to impose sentences that violate common sense," said Rep. Scott. "To add insult to injury, studies have shown that mandatory minimum sentences fail to reduce crime. Our bill will give discretion back to federal judges, so that they can consider all the facts, issues, and circumstances before sentencing."

Mandatory minimums force federal judges to issue indiscriminate punishments, regardless of involvement, criminal history, mental health, addiction, and other mitigating factors.

The Justice Safety Valve Act would apply the current "safety valve" provision to all federal crimes, restoring proportionality, fairness, and rationality to federal sentencing by allowing federal judges to tailor sentences on a case-by-case basis. Such judicial discretion would help reduce the bloated federal prison population and tackle dangerous overcrowding while ensuring sentences fit the circumstances of the crime.

This landmark bipartisan, bicameral legislation would also reduce correctional spending, which currently accounts for almost a third of the Department of Justice"s annual budget. This would allow the Department to focus more on victim services, state and local law enforcement, staffing, investigation, and prosecution.

The Supreme Court sometimes makes prisoners retroactively innocent of their crimes with rulings on federal criminal law. When that happens, defendants get an opportunity to scrap their convictions.

After hearing oral arguments on Nov. 1, the justices may decide to give him a path to freedom, potentially creating an exit door for thousands of people who are languishing in federal prisons for what are no longer crimes.

Because federal prisoners are a small fraction of the people who are incarcerated in the United States, the ruling in Jones v. Hendrix won"t be as sweeping as other high court decisions delving into the habeas process, such as the one in Shinn v. Ramirez University of Virginia School of Law"s Supreme Court Litigation Clinic, who represents Jones.

Affirming his conviction on Sept. 12, 2001, the panel cited its own precedent in United States v. Kind, declaring that "the government need not prove knowledge, but only the fact of a prior felony conviction," to prove that a defendant was guilty under the felon-in-possession statute. In the following two decades he spent behind bars, Jones sought to have his convictions tossed with claims of ineffective counsel, Brady violations and other constitutional errors, to no avail.

The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas, and then the Eighth Circuit, however, denied him habeas relief, saying they lacked jurisdiction in hearing his claims. They argued he could not ask for a writ, because Section 2255"s safety valve could not be triggered in his case.

Jones, who is now 46 years old and is slated for release on Sept. 7, 2023, didn"t let go. Ortiz filed a petition for certiorari on his behalf on Dec. 7, 2021, asking the Supreme Court to resolve a "deep and mature circuit split" on the reach of the safety valve. On May 16, the justices agreed to hear the case.

In 1948, Congress gave federal prisoners the option to challenge their sentence or conviction by filing a motion under Section 2255 of Title 28 of the U.S. Code, largely replacing the traditional habeas action process, which requires filing a petition under Section 2241.

The omission of that claim in his original motion to vacate precluded Jones from raising it again in later habeas actions, a fact that became crucial to his case.

Blume said that the Supreme Court ruling in the case will likely fall into one of three scenarios. It could dismiss Jones" habeas petition if justices agree with Hendrix the evidence is overwhelming that Jones committed a crime; it could embrace Jones" view that the habeas writ under Section 2241 is intended to address the type of claims he raised when Section 2255 motions are not viable. Or it could endorse the U.S. government"s view and shut down that avenue for using habeas corpus.

Federal sentencing law has been indefensibly harsh for a generation, but in theory it has contained a safety valve called compassionate release. The 1984 Sentencing Reform Act gives federal courts the power to reduce sentences of federal prisoners for “extraordinary and compelling reasons,” like a terminal illness.

In practice, though, the Bureau of Prisons and the Justice Department, which oversees the bureau, have not just failed to make use of this humane and practical program, but have crippled it. That is the disturbing and well-substantiated conclusion of a new report by Human Rights Watch and Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

When the 1984 law was passed, the Senate Judiciary Committee said compassionate release was intended for “the unusual case in which the defendant’s circumstances are so changed, such as by terminal illness, that it would be inequitable to continue the confinement of the prisoner.” The Bureau of Prisons was to be responsible for petitioning a court on a prisoner’s behalf, and the court was tasked with balancing a proposal for release against the potential risk to public safety of freeing the prisoner.

The group is called the Correctional Vendors Association, an organization that represents companies that use prison labor to produce eve

8613371530291

8613371530291