justice safety valve act for sale

Proposed in March 2013, the Justice Safety Valve Act would allow federal judges to hand down sentences below current mandatory minimums if: The mandatory minimum sentence would not accomplish the goal that a sentence be sufficient, but not greater than necessary

The factors the judged considered in arriving at the lower sentence are put in writing and must be based on the language is based on the language of 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a)

This proposed updated safety valve would apply to any federal conviction that has been prescribed a mandatory minimum sentence. As written, it would not apply retroactively; inmates already serving a mandatory minimum sentence would not be allowed to request a lesser sentence or re-sentencing based on the Act. It would only apply to federal sentencing; North Carolina would have to enact its own legislation to change state mandatory minimum sentencing.

In 2012, there were 219,000 inmates being held in federal institutions run by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). In 1980, there were only 25,000. Approximately one-quarter of the Justice Department’s budget is spent on corrections. Over 10,000 people received federal mandatory minimum sentences in 2010.

In addition to these statistics, the application of mandatory minimum sentences leads to absurdly long sentences being imposed, at great taxpayer expense, on non-violent individuals. The organization Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM) details how mandatory minimums have resulted in substantial – and unfair – punishments for low-level crimes, including these two examples: Weldon Angelos: Mr. Angelos was sentenced to 55 years in prison after making several small drug sales to a government informant. Several weapons were found in his home and the informant reported seeing a weapon in Mr. Angelos’ possession during at least two buys. He was charged with several counts of possessing a gun during a drug trafficking offense, leading to the substantial sentence, despite having no major criminal record, dealing only in small amounts of weed, and never using a weapon during the course of a drug transaction.

John Hise: Mr. Hise was sentenced to 10 years on a drug conspiracy charge. He had sold red phosphorous to a friend who was involved in meth manufacturing. Mr. Hise stopped aiding his friend, but not before authorities had caught on. He was convicted and sentenced to 10 years despite police finding no evidence of red phosphorous in his home during a search. Mr. Hise was ineligible for the current safety valve law because of a possession and DUI offense already on his record.

The use of mandatory minimums that allow little discretion for judges to depart to a lower sentence have contributed to the growing prison population and expense of housing those arbitrarily required to spend years in prison. There is certainly room for improvement. Expanding this safety valve to all mandatory minimum sentences would reduce the long-term prison population while still ensuring that the goals of sentencing are met.

The first question a federal judge must consider in deciding whether or not he or she will sentence a person convicted of a federal offense below the mandatory minimum under the proposed Act is whether the mandatory minimum sentence would over punish that person. In other words, would the mandatory minimum put the person in prison for longer than is necessary to meet the goals of sentencing?

The proposed Act would ensure that the goals of sentencing return to the forefront of determining an appropriate prison term rather than substituting the judgment of Congress for that of the presiding judge during the sentencing phase of the federal criminal process.

There are currently just under 200 mandatory minimum sentences for federal crimes on the books, but only federal drug offenses are subject to an existing sentencing safety valve. The actual text of the existing sentencing safety valve can be found at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f).

In order for a federal judge to apply the existing safety valve to sentencing for a federal drug crime, he or she must make the following findings: No one was injured during the commission of the drug offense

These criteria are strict and minimize the number of people who could be saved from lengthy, arbitrary prison sentences. The legal possession of a gun during the commission of a drug crime has been used to deny the application of the safety valve as has prior criminal history that included only misdemeanor or petty offenses. In effect, the current safety valve legislation allows only about one-quarter of those sentenced on federal drug offenses to take advantage of the deviation from mandatory minimums each year.

Another exception to mandatory minimum sentencing, substantial assistance, is often unavailable to low-level drug offenders. Often those who are tasked with transporting or selling drugs, or who are considered mules, have little if any information about the actual drug ring itself. These people are then not eligible for a reduced sentence below a mandatory minimum because they have no information to provide prosecutors; they are incapable of providing substantial assistance.

Identical versions of the Act were introduced in the House and Senate, H.R. 1695 and S. 619. Both have been referred to the committee for review. The proposed Safety Valve Act would expand the application of the safety valve beyond drug crimes and would allow judges to ensure that sentencing goals are met while not over-punishing individuals and overcrowding the nation’s prison system.

However, the Safety Valve Act is no substitute for an experienced federal defense lawyer on the side of anyone facing federal charges; it is not a get out of jail card. If a judge deviates below mandatory minimums in sentencing, he or she would still be required to apply the federal sentencing guidelines in determining an appropriate sentence.

This informational article about the proposed Justice Safety Valve Act is provided by the attorneys of Roberts Law Group, PLLC, a criminal defense law firm dedicated to the rights of those accused of a crime throughout North Carolina. To learn more about the firm, please like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter or Google+ to get the latest updates on safety and criminal defense matters in North Carolina. For a free consultation with a Charlotte defense lawyer from Roberts Law Group, please call contact our law firm online.

After conducting an investigation and communicating with the prosecutor about the facts and circumstances indicating that our client acted in self-defense, the case was dismissed and deemed a justifiable homicide.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13740093/1094199730.jpg.jpg)

Congress’s new bipartisan task force on overcriminalization in the justice system held its first hearing earlier this month. It was a timely meeting: national crime rates are at historic lows, yet the federal prison system is operating at close to 40 percent over capacity.

Representative Karen Bass, a California Democrat, asked a panel of experts about the problem of mandatory minimum sentences, which contribute to prison overcrowding and rising costs. In the 16-year period through fiscal 2011, the annual number of federal inmates increased from 37,091 to 76,216, with mandatory minimum sentences a driving factor. Almost half of them are in for drugs.

Both the Senate and the House are considering a bipartisan bill to allow federal judges more flexibility in sentencing in the 195 federal crimes that carry mandatory minimums. The bill, called the Justice Safety Valve Act, deserves committee hearings and passage soon.

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Today, Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT), Senator Rand Paul (R-KY), Representative Thomas Massie (R-KY), and Representative Bobby Scott (D-VA) introduced the Justice Safety Valve Act in the Senate and House of Representatives. The Justice Safety Valve Act would give federal judges the ability to impose sentences below mandatory minimums in appropriate cases based upon mitigating factors.

“The one-size-fits-all approach of federally mandated minimums does not give judges the latitude they need to ensure that punishments fit the crimes. As a result, nonviolent offenders are sometimes given excessive sentences,” said Rep. Massie. “Furthermore, public safety can be compromised because violent offenders are released from our nation"s overcrowded prisons to make room for nonviolent offenders.”

“Mandatory minimum sentences have been studied extensively and have been found to distort rational sentencing systems, discriminate against minorities, waste money, and often require a judge to impose sentences that violate common sense,” stated Rep. Scott. “To add insult to injury, studies have shown that mandatory minimum sentences fail to reduce crime. Our bill will give discretion back to federal judges so that they can consider all the facts, issues, and circumstances before sentencing.”

Mandatory minimums force federal judges to issue indiscriminate punishments, regardless of involvement, criminal history, mental health, addiction, and other mitigating factors. The Justice Safety Valve Act would apply the current "safety valve" provision to all federal crimes, allowing federal judges to tailor sentences on a case-by-case basis. Such judicial discretion would go a long way in helping to reduce the bloated federal prison population while also ensuring sentences fit the circumstances of the crime.

This landmark bipartisan, bicameral legislation would restore proportionality, fairness, and rationality to federal sentencing. It would also reduce the overcrowding in federal facilities, which are currently operating at between 35-50% above their rated capacity, posing risks to both inmates and officers. Lastly, it would reduce correctional spending, which currently accounts for almost a third of the Department of Justice’s annual budget. Every dollar spent on corrections is one that deprives the Department of Justice’s ability to fund victim services, state and local law enforcement, staffing, investigation, and prosecution.

The Justice Safety Valve Act takes effect Nov. 1. Its author, state Rep. Pam Peterson, R-Tulsa, said she hasn’t heard about any defense attorneys using continuance motions in advance of her bill officially becoming law. House Bill 1518 passed the Legislature this year.

Under its provisions, a judge can bypass mandatory minimum sentencing only if there are substantial and compelling reasons that a minimum sentence would cause injustice.

“We all see the need for this,” Peterson said. “It’s a real bipartisan effort, all kinds of people working together to find workable solutions so we don’t just put away people we’re mad at. We need to make sure those (prison) beds are reserved for people we’re afraid of, and for protection of public safety.”

A “safety valve” is an exception to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. A safety valve allows a judge to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum term if certain conditions are met. Safety valves can be broad or narrow, applying to many or few crimes (e.g., drug crimes only) or types of offenders (e.g., nonviolent offenders). They do not repeal or eliminate mandatory minimum sentences. However, safety valves save taxpayers money because they allow courts to give shorter, more appropriate prison sentences to offenders who pose less of a public safety threat. This saves our scarce taxpayer dollars and prison beds for those who are most deserving of the mandatory minimum term and present the biggest danger to society.

The Problem:Under current federal law, there is only one safety valve, and it applies only to first-time, nonviolent drug offenders whose cases did not involve guns. FAMM was instrumental in the passage of this safety valve, in 1994. Since then, more than 95,000 nonviolent drug offenders have received fairer sentences because of it, saving taxpayers billions. But it is a very narrow exception: in FY 2015, only 13 percent of all drug offenders qualified for the exception.

Mere presence of even a lawfully purchased and registered gun in a person’s home or car is enough to disqualify a nonviolent drug offender from the safety valve,

Even very minor prior infractions (e.g., careless driving) that resulted in no prison time can disqualify an otherwise worthy low-level drug offender from the safety valve, and

The Solution:Create a broader safety valve that applies to all mandatory minimum sentences, and expand the existing drug safety valve to cover more low-level offenders.

NORMAN — For what is likely the first time in Cleveland County District Court, a local defense attorney filed a motion to use the Justice Safety Valve Act, a new piece of Oklahoma legislation that went into effect Nov. 1.

Schambron, 22, of Norman entered a guilty plea Thursday for a felony count of false declaration of a pawnbroker. Since Schambron has been previously convicted, the range of punishment is 2 years in prison to life in prison. The motion called the minimum mandatory sentence an “‘injustice’ based on the facts as they currently are.”

The Act authorizes courts to depart from mandatory minimum sentencing requirements under certain circumstances and if the person is not a threat or danger to the community.

Virgin said it’s the judges who are seeing all the facts and circumstances of the case, and sometimes statutes do not fit, or do not make sense when it comes to sentencing.

“I’m looking forward to using this vehicle that legislation created in the courts to help people,” Talley said. “I’m wildly optimistic of the benefit and impact it can have on the community as a whole.”

Kris Steele, former Speaker of the Oklahoma House of Representatives and current executive director of The Education and Employment Ministry, said the act has the potential to produce a better outcome than sending a person to jail or prison, which would allow the state to make better use of limited resources.

If a person is incarcerated without getting the help needed, when that person finishes serving their sentence and re-enters the community, they are often times at greater risk to public safety than before because those issues were never addressed, Steele said.

The Justice Safety Valve Act states if a mandatory minimum sentence of imprisonment isn’t necessary, then based on a risk and needs assessment the offender “is eligible for an alternative court, a diversion program or community sentencing, without regard to exclusions because of previous convictions, and has been accepted to the same, pending sentence.”

The motion Talley filed Wednesday to use the Act states Schambron is seeking a departure of a minimum mandatory sentence only in the false declaration of a pawnbroker case.

The Act represents a dramatically different and enlightened approach to fighting crime that is focused on rehabilitation, reintegration, and sentencing reduction, rather than the tough-on-crime, lock-them-up rhetoric of the past.

While not containing many reforms urged by criminal justice experts, including these authors, what is overwhelmingly clear from the legislation is that Congress recognizes not just the importance of data analysis in reducing recidivism (that will be addressed in subsequent articles), but also recognizes that long prison sentences really ought to be reserved only for the more dangerous offenders.

Perhaps the Act’s most far-reaching change to sentencing law is its expansion of the application of the Safety Valve—the provision of law that reduces a defendant’s offense level by two and allows judges to disregard an otherwise applicable mandatory minimum penalty if the defendant meets certain criteria. It is aimed at providing qualifying low-level, non-violent drug offenders a means of avoiding an otherwise draconian penalty. In fiscal year 2017, nearly one-third of all drug offenders were found eligible for the Safety Valve.

Until the Act, one of the criteria for the Safety Valve was that a defendant could not have more than a single criminal history point. This generally meant that a defendant with as little as a single prior misdemeanor conviction that resulted in a sentence of more than 60 days was precluded from receiving the Safety Valve.

Section 402 of the Act relaxes the criminal history point criterion to allow a defendant to have up to four criminal history points and still be eligible for the Safety Valve (provided all other criteria are met). Now, even a prior felony conviction would not per se render a defendant ineligible from receiving the Safety Valve so long as the prior felony did not result in a sentence of more than 13 months’ imprisonment.

Importantly, for purposes of the Safety Valve, prior sentences of 60 days or less, which generally result in one criminal history point, are never counted. However, any prior sentences of more than 13 months, or more than 60 days in the case of a violent offense, precludes application of the Safety Valve regardless of whether the criminal history points exceed four.

These changes to the Safety Valve criteria are not retroactive in any way, and only apply to convictions entered on or after the enactment of the Act. Despite this, it still is estimated that these changes to the Safety Valve will impact over 2,000 offenders annually.

Currently, defendants convicted of certain drug felonies are subject to a mandatory minimum 20 years’ imprisonment if they previously were convicted of a single drug felony. If they have two or more prior drug felonies, then the mandatory minimum becomes life imprisonment. Section 401 of the Act reduces these mandatory minimums to 15 years and 25 years respectively.

These amendments apply to any pending cases, except if sentencing already has occurred. Thus, they are not fully retroactive. Had they been made fully retroactive, it is estimated they would have reduced the sentences of just over 3,000 inmates. As it stands, these reduced mandatory minima are estimated to impact only 56 offenders annually.

Section 403 of the Act eliminates the so-called “stacking” of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A) penalties. Section 924(c) provides for various mandatory consecutive penalties for the possession, use, or discharge of a firearm during the commission of a felony violent or drug offense. However, for a “second or subsequent conviction” of 924(c), the mandatory consecutive penalty increases to 25 years.

Now, under the Act, to avoid such an absurd and draconian result, Congress has clarified that the 25-year mandatory consecutive penalty only applies “after a prior conviction under this subsection has become final.” Thus, the enhanced mandatory consecutive penalty no longer can be applied to multiple counts of 924(c) violations.

Finally, Section 404 of the Act makes the changes brought about by the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 fully retroactive. As the U.S. Sentencing Commission’s “2015 Report to Congress: Impact of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010,” explained: “The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (FSA), enacted August 3, 2010, reduced the statutory penalties for crack cocaine offenses to produce an 18-to-1 crack-to-powder drug quantity ratio. The FSA eliminated the mandatory minimum sentence for simple possession of crack cocaine and increased statutory fines. It also directed the Commission to amend the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines to account for specified aggravating and mitigating circumstances in drug trafficking offenses involving any drug type.”

While the Act now makes the FSA fully retroactive, those prisoners who already have sought a reduction under the FSA and either received one, or their application was otherwise adjudicated on the merits, are not eligible for a second bite at the apple. It is estimated that full retroactive application of the FSA will impact 2,660 offenders.

Reducing the severity and frequency of some draconian mandatory minimum penalties, increasing the applicability of the safety valve, and giving full retroactive effect to the FSA signals a more sane approach to sentencing, which will help address prison overpopulation, while ensuring scarce prison space is reserved only for the more dangerous offenders.

Mark H. Allenbaugh, co-founder of Sentencing Stats, LLC, is a nationally recognized expert on federal sentencing, law, policy, and practice. A former staff attorney for the U.S. Sentencing Commission, he is a co-editor of Sentencing, Sanctions, and Corrections: Federal and State Law, Policy, and Practice (2nd ed., Foundation Press, 2002). He can be reached at mark@sentencingstats.com.

This is a brief discussion of the law associated with themandatory minimum sentencing provisions offederal controlled substance(drug)lawsanddrug-related federal firearms and recidivist statutes.Thesemandatory minimums, however, are not as mandatory as they might appear.The government may elect not to prosecute the underlying offenses.Federal courtsmaydisregardotherwise applicable mandatory sentencing requirementsat the behest of the government.Thefederal courtsmay also bypasssome ofthemfor the benefit of certain low-level, nonviolent offenders withvirtually spotlesscriminal recordsunder the so-called"safety valve" provision.Finally, in cases where the mandatory minimums would usually apply, thePresident may pardon offenders or commute their sentences before the minimum term of imprisonment has been served.Be that as it may,sentencing in drug cases,particularlymandatory minimum drug sentencing, hascontributedtoan explosion in thefederal prison population and attendant costs.Thus, the federal inmate population at the end of 1976 was 23,566, and at the end of 1986 it was 36,042.OnJanuary 4, 2018,the federal inmate population was 183,493.As of September 30, 2016, 49.1% of federal inmates were drug offenders and 72.3% of those were convicted of an offense carrying a mandatory minimum.In 1976, federal prisons cost $183.914 million; in 1986, $550.014 million; and in 2016, $6.751 billion (est.).

Federal mandatory minimum sentencing statutes have existed since the dawn of the Republic. When the first Congress assembled, it enacted several mandatory minimums, each of them a capital offense.

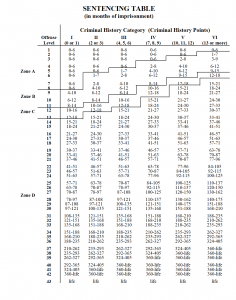

Then, in 1984, Congress enacted the Sentencing Reform Act that created the United States Sentencing Commission and authorized it to promulgate then binding sentencing guidelines.

The hate crime legislation enacted in 2009 directed the U.S. Sentencing Commission to submit a second report on federal mandatory minimums.Booker decision and its progeny, the Guidelines became but the first step in the sentencing process.

The second Commission report recommended that Congress consider expanding eligibility for the safety valve, and adjusting the scope, severity, and the prior offenses that trigger the recidivist provisions under firearm statute

6. Statutory relief plays a significant role in the application and impact of drug mandatory minimum penalties, and results in significant reduced sentences when applied.

8. However, neither the statutory safety valve provision at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), nor the substantial assistance provision of 18 U.S.C. § 3553(e) fully ameliorate the impact of drug mandatory minimum penalties on relatively low-level offenders.

Section 841(a) outlaws knowingly or intentionally manufacturing, distributing, dispensing, or possessing with the intent to distribute or dispense controlled substances except as otherwise authorized by the Controlled Substances Act.

Manufacture: For purposes of Section 841(a), ""manufacture" means the production … or processing of a drug, and the term "production" includes the manufacture, planting, cultivation, growing, or harvesting of a controlled substance."

Distribute or Dispense: The Controlled Substances Act defines the term "distribute" broadly. The term encompasses any transfer of a controlled substance other than dispensing it.

Possession with Intent to Distribute or Dispense: The government may satisfy the possession element with evidence of either actual or constructive possession.

The felony drug convictionsthat trigger the sentencing enhancementinclude federal, state, and foreign convictions.The "serious bodily injury" enhancement is confined to bodily injuries which involve"(A) a substantial risk of death;(B) protracted and obvious disfigurement; or(C) protracted loss or impairment of the function of a bodily member, organ, or mental faculty."And, the "if death results" enhancement is availableonlyif the drugs provided by the defendant were the "but-for" cause of death;it is not available if the drugs supplied were merely a contributing cause.The same "but for" standard presumably applies with equal force to the "serious bodily injury" enhancement.

To prove an attempt to violate Section 841(a) "the government must establish beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant (a) had the intent to commit the object crime and (b) engaged in conduct amounting to a substantial step towards its commission. For a defendant to have taken a substantial step, he must have engaged in more than mere preparation, but may have stopped short of the last act necessary for the actual commission of the substantive crime."

Although it technically demonstrates an agreement to distribute a controlled substance, proof of a small, one-time sale of a controlled substance is ordinarily not considered sufficient for a conspiracy conviction. "[T]he factors that demonstrate a defendant was part of a conspiracy rather than in a mere buyer/seller relationship with that conspiracy include: (1) the length of affiliation between the defendant and the conspiracy; (2) whether there is an established method of payment; (3) the extent to which transactions are standardized; (4) whether there is a demonstrated level of mutual trust; (5) whether the transactions involved large amounts of drugs; and (6) whether the defendant purchased his drugs on credit."

Section 960a doubles the otherwise applicable mandatory minimum sentence for drug trafficking (including an attempt or conspiracy to traffic) when the offense is committed in order to fund a terrorist activity or terrorist organization.

Section 924(c) outlaws possession of a firearm in furtherance of, or use of a firearm during and in relation to, a predicate offense. A "firearm" for purposes of Section 924(c) includes not only guns ("weapons ... which will or [are] designed to or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive"), but silencers and explosives as well.

Section 924(c) is triggered when a firearm is used or possessed in furtherance of a predicate offense. The predicate offenses are crimes of violence and certain drug trafficking crimes. The drug trafficking predicates include any felony violation of the Controlled Substances Act, the Controlled Substances Import and Export Act, or the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act.

Although the Supreme Court has determined that acquiring a firearm in an illegal drug transaction does not constitute "use" in violation of Section 924(c),

The "use" outlawed in the use or carriage branch of Section 924(c) requires that a firearm be actively employed "during and in relation to" a predicate offense – that is, either a crime of violence or a drug trafficking offense.

Prior to the division, the Supreme Court had identified as an element of a separate offense (rather than a sentencing factor) the question of whether a machine gun was the firearm used during and in relation to a predicate offense.

A number of defendants have sought refuge in the clause of Section 924(c), which introduces the section"s mandatory minimum penalties with an exception: "[e]xcept to the extent that a greater minimum sentence is otherwise provided by this subsection or by any other provision of law." Defendants at one time argued that the mandatory minimums of Section 924(c) become inapplicable when the defendant was subject to a higher mandatory minimum under the predicate drug trafficking offense under the Armed Career Criminal Act (18 U.S.C. § 924(e)), or some other provision of law.Abbottv. United States.

There is "no authority to ignore [an otherwise qualified] conviction because of its age or its underlying circumstances. Such considerations are irrelevant ... under the Act."

Low-level drug offenders can escape some of the mandatory minimum sentences for which they qualify under the safety valve found in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f). Congress created the safety valve after it became concerned that the mandatory minimum sentencing provisions could have resulted in equally severe penalties for both the more and the less culpable offenders.

The safety valve is not available to avoid the mandatory minimum sentences that attend other offenses, even those closely related to the covered offenses. Section 860 (21 U.S.C. § 860), which outlaws violations of Section 841 near schools, playgrounds, or public housing facilities and sets the penalties for violation at twice what they would be under Section 841, is not covered. Those charged with a violation of Section 860 are not eligible for relief under the safety valve provisions.

For the convictions to which the safety valve does apply, the defendant must convince the sentencing court by a preponderance of the evidence that he satisfies each of the safety valve"s five requirements.

The safety valve has two disqualifications designed to reserve its benefits to the nonviolent. One involves instances in which the offense resulted in death or serious bodily injury. The other involves the use of violence, threats, or the possession of weapons. The weapon or threat of violence disqualification turns upon the defendant"s conduct or the conduct of those he "aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused."

The Sentencing Guidelines define "serious bodily injury" for purposes of Section 3553(f)(3) as an "injury involving extreme physical pain or the protracted impairment of a function of a bodily member, organ, or mental faculty; or requiring medical intervention such as surgery, hospitalization, or physical rehabilitation."

The Guidelines disqualify anyone who acted as a manager of the criminal enterprise or who receives a Guideline level increase for his aggravated role in the offense.

The most heavily litigated safety valve criterion requires full disclosure on the part of the defendant. The requirement extends not only to information concerning the crimes of conviction, but also to information concerning other crimes that "were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan," including uncharged related conduct.

The substantial assistance provision was enacted with little fanfare in the twilight of the 99th Congress as part of the wide-ranging Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, legislation that established or increased a number of mandatory minimum sentencing provisions.

Defendants sentenced to mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment have challenged their sentences on a number of constitutional grounds beginning with Congress"s legislative authority and ranging from cruel and unusual punishment through ex post facto and double jeopardy to equal protection and due process. Each constitutional provision defines outer boundaries that a mandatory minimum sentence and the substantive offense to which it is attached must be crafted to honor.

Many of the federal laws with mandatory minimum sentencing requirements were enacted pursuant to Congress"s legislative authority over crimes occurring on the high seas or within federal enclaves,

"The Congress shall have Power ... To regulate Commerce with Foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with Indian Tribes."United States v. Lopez, "[f]irst, Congress may regulate the use of the channels of interstate commerce.... Second, Congress is empowered to regulate and protect the instrumentalities of interstate commerce, or persons or things in interstate commerce, even though the threat may come only from intrastate activities.... Finally, Congress"s commerce authority includes the power to regulate those activities having a substantial relation to interstate commerce."

Applying these standards, the LopezCourt concluded that the Commerce Clause did not authorize Congress to enact a particular statute which purported to outlaw possession of a firearm on school property. Because the statute addressed neither the channels nor instrumentalities of interstate commerce, its survival turned upon whether it came within Congress"s power to regulate activities that have a substantial impact on interstate commerce.

Given the enforcement difficulties that attend distinguishing between marijuana cultivated locally and marijuana grown elsewhere and concerns about diversion into illicit channels, we have no difficulty concluding that Congress had a rational basis for believing that failure to regulate the intrastate manufacture and possession of marijuana would leave a gaping hole in the CSA [Controlled Substances Act]. Thus ... when it enacted comprehensive legislation to regulate the interstate market in a fungible commodity, Congress was acting well within its authority to "make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper" to "regulate Commerce ... among the several States." That the regulation ensnares some purely intrastate activity is of no moment."

Justice Scalia, in his Raich concurrence, saw the Necessary and Proper Clause as a necessary Commerce Clause supplement for legislation like the Controlled Substances Act that purports to regulate purely in-state activity.

Five members of the Court concluded that it did not. Two members, Justice Scalia and Chief Justice Rehnquist, simply refused to recognize an Eighth Amendment proportionality requirement, at least in noncapital cases.

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment condemns statutory classifications invidiously based on race, or constitutionally suspect factors. Moreover, "[d]iscrimination on the basis of race odious in all aspects is especially pernicious in the administration of justice."

The Constitution demands that no person "be held to answer for a capital or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury" and that "[i]n all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury."In reWinship decision explained that due process requires that the prosecution prove beyond a reasonable doubt "every fact necessary to constitute the crime" with which an accused is charged.Winship, the question arose whether a statute might authorize or require a more severe penalty for a particular crime based on a fact—not included in the indictment, not found by the jury, and not proven beyond a reasonable doubt. Pennsylvania passed a law under which various serious crimes (rape, robbery, kidnapping, and the like) were subject to a mandatory minimum penalty of imprisonment for five years, if the judge after conviction found by a preponderance of the evidence that the defendant had been in visible possession of a firearm during the commission of the offense.

There followed a number of state and federal statutes under which facts that might earlier have been treated as elements of a new crime were simply classified as sentencing factors. In some instances, the new sentencing factor permitted imposition of a penalty far in excess of that otherwise available for the underlying offense. For instance, the Supreme Court found no constitutional defect in a statute which punished a deported alien for returning to the United States by imprisonment for not more than 2 years, but which permitted the alien to be sentenced to imprisonment for not more than 20 years upon a post-trial, judicial determination that the alien had been convicted of a serious crime following deportation.

Perhaps uneasy with the implications, the Court soon made it clear in Apprendithat, "under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment and the notice and jury trial guarantees of the Sixth Amendment, any fact (other than prior conviction) that increases the maximum penalty for a crime must be charged in an indictment, submitted to a jury, and proven beyond a reasonable doubt."McMillan"s mandatory minimum determination in light of the Apprendi.

Harris drew a distinction between facts that increase the statutory maximum and facts that increase only the mandatory minimum. We conclude that this distinction is inconsistent with our decision in Apprendi and with the original meaning of the Sixth Amendment. Any fact that, by law, increases the penalty for a crime is an element that must be submitted to the jury and found beyond a reasonable doubt. Mandatory minimum sentences increase the penalty for a crime. It follows, then, that any fact that increases the mandatory minimum is an element that must be submitted to the jury.

Neither Apprendi nor Alleyne limits Congress"s authority to establish mandatory minimum sentences or limits the authority of the courts to impose them. They simply dictate the procedural safeguards that must accompany the exercise of that authority. Thus, the lower federal appellate courts have held that the neither the Fifth nor Sixth Amendment requires that "facts that determine whether a defendant is eligible under the safety valve for a sentence below the statutory minimum" need be found by the jury beyond a reasonable doubt.

We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

Congress changed all of that in the First Step Act. In expanding the number of people covered by the safety valve, Congress wrote that a defendant now must only show that he or she “does not have… (A) more than 4 criminal history points… (B) a prior 3-point offense… and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense.”

The “safety valve” was one of the only sensible things to come out of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the bill championed by then-Senator Joe Biden that, a quarter-century later, has been used to brand him a mass-incarcerating racist. The safety valve was intended to let people convicted of drug offenses as first-timers avoid the crushing mandatory minimum sentences that Congress had imposed on just about all drug dealing.

Eric Lopez got caught smuggling meth across the border. Everyone agreed he qualified for the safety valve except for his criminal history. Eric had one prior 3-point offense, and the government argued that was enough to disqualify him. Eric argued that the First Step Actamendment to the “safety valve” meant he had to have all three predicates: more than 4 points, one 3-point prior, and one 2-point prior violent offense.

Last week, the 9th Circuit agreed. In a decision that dramatically expands the reach of the safety valve, the Circuit applied the rules of statutory construction and held that the First Step amendment was unambiguous. “Put another way, we hold that ‘and’ means ‘and.’”

“We recognize that § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language might be viewed as a considerable departure from the prior version of § 3553(f)(1), which barred any defendant from safety-valve relief if he or she had more than one criminal-history point under the Sentencing Guidelines… As a result, § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language could possibly result in more defendants receiving safety-valve relief than some in Congress anticipated… But sometimes Congress uses words that reach further than some members of Congress may have expected… We cannot ignore Congress’s plain and unambiguous language just because a statute might reach further than some in Congress expected… Section 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language, the Senate’s own legislative drafting manual, § 3553(f)(1)’s structure as a conjunctive negative proof, and the canon of consistent usage result in only one plausible reading of § 3553(f)(1)’s“and” here: “And” is conjunctive. If Congress meant § 3553(f)(1)’s “and” to mean “or,” it has the authority to amend the statute accordingly. We do not.”

A functioning justice system must work to protect the innocent, while simultaneously holding accountable and rehabilitating those who commit crimes. We must comprehensively overhaul a criminal justice system that, in its current form, is guided by outdated laws and perpetuates structural failures in society. Our judicial system sets up those who have offended and served their sentences to continued failure, even after they have served their time.

As a nation, we incarcerate more of our own citizens than any other country in the world – often times for non-violent drug offenses. Past reforms meant to keep our communities safer have resulted in disproportionately high incarceration rates among people of color, splitting families apart and helping to continue cycles of poverty. Despite the creation of innovative tools at the local level in King County to institute diversionary “safety valve” mental health, drug rehabilitation, and veterans treatment courts, these resources do not currently exist at the federal level. Communities of color still face disproportionate mandatory minimum sentences, with charges often stacking on top of one another. The vast majority of inmates leaving prison face long-term unemployment, with employers often unwilling to consider them due to their records.

As a former prosecutor, I have had a unique exposure to the intricacies of our judicial system. The men and women who work in law enforcement, as prosecutors, public defenders, judges, and corrections officers shoulder the immense duty of keeping our communities safe. These individuals must uphold this responsibility while at the same time assuring that the system remains fair and balanced, and that individuals are treated and judged equally under the law. The time has come to make important adjustments to the way we handle criminal justice in our country.

Overhauling Our Judicial System: Cosponsor of H.R. 2435, the Justice Safety Valve Act –Federal mandatory minimums must be rolled back. These laws have created massive disparities, with communities of color facing dramatically higher rates of incarceration. This bill would allow judges to break from mandatory minimum penalties, assessing lower sentences where appropriate. I have consistently opposed any legislation that imposes new mandatory minimums – this one size fits all approach cannot continue.

Ending Private Prisons and Restoring Fairness to the System: Cosponsor of H.R. 3227, the Justice is Not For Sale Act - As a country, we must end the practice of turning the incarceration of citizens into a business transaction. I am an original cosponsor of the Justice is Not For Sale Act. This legislation, also introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders in the U.S. Senate, would end all private prison contracts at the federal, state, and local level – including immigration detention facilities. H.R. 3227 would also reinstate the federal parole system to allow the US Sentencing Commission to make individualized, risk-based determinations regarding each prisoner.

Ending Racial Profiling: Original Cosponsor of H.R. 1498, the End Racial Profiling Act – legislation prohibiting any law enforcement agent or agency from engaging in racial profiling, and also allows for any individual injured by racial profiling the right to file a lawsuit. H.R. 1498 requires federal law enforcement to develop and maintain policies to eliminate profiling, and require state/local/tribal law enforcement agencies who apply for certain federal grants to develop similar policies.

Ensuring Transparency: Original Cosponsor of H.R. 1870, the Police Training and Independent Review Act –To receive federal law enforcement grants under this bill, states must pass laws requiring the appointment of a special prosecutor to review cases where an officer is a defendant, including officer-involved shootings. It also requires training on racial and ethnic bias at law enforcement academies.

Helping With Reentry: Cosponsor of H.R. 2899, the Second Chance Act -legislation that would reauthorize the Second Chance Act, which continues funding for reentry programs at the state and local levels that have been proven to reduce recidivism, lead to better outcomes for those released from prison, and lower the amount our nation spends on incarceration. We lock up more of our own people than any other country in the world.

Equal Employment Opportunities through Banning the Box: Cosponsor of H.R. 1905, the Fair Chance Act -This “ban the box” legislation prohibits federal agencies and primary federal contractors from asking about an applicant’s criminal history on an initial employment application. This legislation allows applicants who have completed their prison sentences to build a strong foundation for a career.

Leadership at the federal level is critical to ensure wider enactment of restorative justice programs like those spearheaded by Washington State. As we work towards common-sense reforms to our criminal justice system, I greatly value the continuing information, opinions and experiences shared with me by my constituents about these critical topics. We must chart a new course if we are to build a stronger tomorrow.

In order to rebuild and preserve relationships between the judicial and law enforcement systems and the communities, it is crucial that safety and transparency are prioritized. While the vast majority of law enforcement officers in our country operate with the highest degree of professionalism and without bias, the specter of racial profiling has greatly impacted relationships with some communities of color. It is critical that we address the underlying issues that have created such divides.

It is for that reason that I have cosponsored legislation that would establish pilot grant programs through the Department of Justice (DOJ) using existing funding to assist state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies with the costs of purchasing or leasing Body Worn Cameras (BWCs). In the wake of the recent alarming events involving law enforcement across the country, body-worn cameras have emerged as a potentially powerful transparency tool to communities, as well as police officers. The use of cameras is not a perfect solution, and the DOJ must conduct studies on the impact of BWCs on not only reducing excessive use of force by police, but also increasing accountability of officers, the effects of BWCs on both officer safety and public safety, and best practices for data management.

I also support and have cosponsored legislation designed to enforce the constitutional right to equal protection of the laws by changing the policies and procedures underlying the practice of profiling, such as the End Racial Profiling Act. I have consistently supported programs such as the Byrne Justice Assistance Grants (JAG) and Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) programs to improve the support and responsiveness that police agencies can provide to the communities they serve. The Byrne JAG program provides support for many parts of the criminal justice system, including community-based criminal justice initiatives, crime prevention education, hiring patrol officers, and programs such as veterans treatment courts. Byrne JAG also supports anti-human trafficking training for local departments to identify and rescue victims through coordination with federal law enforcement and victims service providers. The COPS Office and its corresponding programs provide invaluable resources and technical assistance to state and local law enforcement agencies. It is essential, now more than ever, that these programs be used to encourage reforms, increase training for law enforcement officers, and create trust through community outreach.

This crisis has had a devastating effect on public health and safety in communities across the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), drug overdose deaths now surpass traffic crashes in the number of deaths caused by injury in the U.S, with an average of 120 drug related deaths per day in 2014. Factors such as drastic increases in the number of prescriptions written and dispensed and greater social acceptability for using medications for different purposes has contributed to the growing epidemic of opioid addictions.

While I ultimately am pleased that Congress has begun to address the serious and growing challenge posed by the abuse of prescription and illicit opioids in this country with the passage of the Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Reduction Act in May 2016, the compromise bill failed to include additional emergency funding to support new programs. It is absolutely essential that we recognize the evidence-based fact that remanding these individuals to jail and prison is structurally, as well as morally, wrong. Funding grant programs and other new initiatives is a critical responsibility of Congress that cannot be ignored. More can and must be done to make this a truly comprehensive approach.

While the limited enforcement direction that the DOJ has taken is a positive step, I remain concerned about possible prosecution of Washington State residents who are acting in accordance with state law. I have contacted DOJ numerous times about this issue, and along with other Members of Congress, asking that the DOJ respect voters acting in accordance with state laws, and not enforce federal marijuana laws on those in compliance. I have also spoken directly with officials in the White House and DOJ expressing my concerns. I am committed to protecting the rights of residents in Washington State, and will continue to look for any avenue to ensure legal clarity when it comes to marijuana use.

8613371530291

8613371530291