justice safety valve act of 2013 in stock

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

The Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013 (H.R. 1695 in the House or S. 619 in the Senate) is a bill in the 113th United States Congress.minimum sentences under certain circumstances.

The bill amends the federal criminal US code of the United States title 18, Part II, Chapter 227, Subchapter A, Section 3553 Imposition of a Sentence. It aimed to authorize a federal court to impose a sentence below a statutory minimum if necessary to avoid violating federal provisions prescribing factors courts must consider in imposing a sentence. It requires the court to give parties notice of its intent to impose a lower sentence and to state in writing the factors requiring such a sentence.

On November 21, 2013, the United States Senate Judiciary Committee convened in a rescheduled Executive Business Meeting. The meeting was to discuss and possibly vote on moving forward with the Justice Safety Valve Act. Other related Acts include the S.1410, "The Smarter Sentencing Act of 2013" (Durbin, Lee, Leahy, Whitehouse) and

S.1675, Recidivism Reduction and Public Safety Act of 2013 (Whitehouse, Portman). The Justice Safety Valve Act became one of many new bills to address prison overcrowding and the soaring cost to the American taxpayers. A quorum was not present at the meeting and the Chairman had to postpone discussion and possible vote on the Justice Safety Valve Act. The bills were held over by the Senate Judiciary Committee through the end of 2013 and January 2014. The bills were worked on to merge the language of the Smarter Sentencing Act (H.R. 3382/S. 1410) and the Justice Safety Valve Act (H.R. 1695/S. 619) along with a new bill, S. 1783 the Federal Prison Reform Act of 2013, introduced by John Cornyn (R-TX).

The bill summary was written by the Congressional Research Service, a nonpartisan division of the Library of Congress. It reads, "Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013 - Amends the federal criminal code to authorize a federal court to impose a sentence below a statutory minimum if necessary to avoid violating federal provisions prescribing factors courts must consider in imposing a sentence. Requires the court to give the parties notice of its intent to impose a lower sentence and to state in writing the factors requiring such a sentence."

113th Congress (2013) (April 24, 2013). "H.R. 1695: Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013". Legislation. GovTrack.us. Retrieved October 26, 2013. Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

We hope to make GovTrack more useful to policy professionals like you. Please sign up for our advisory group to be a part of making GovTrack a better tool for what you do.

Our mission is to empower every American with the tools to understand and impact Congress. We hope that with your input we can make GovTrack more accessible to minority and disadvantaged communities who we may currently struggle to reach. Please join our advisory group to let us know what more we can do.

We love educating Americans about how their government works too! Please help us make GovTrack better address the needs of educators by joining our advisory group.

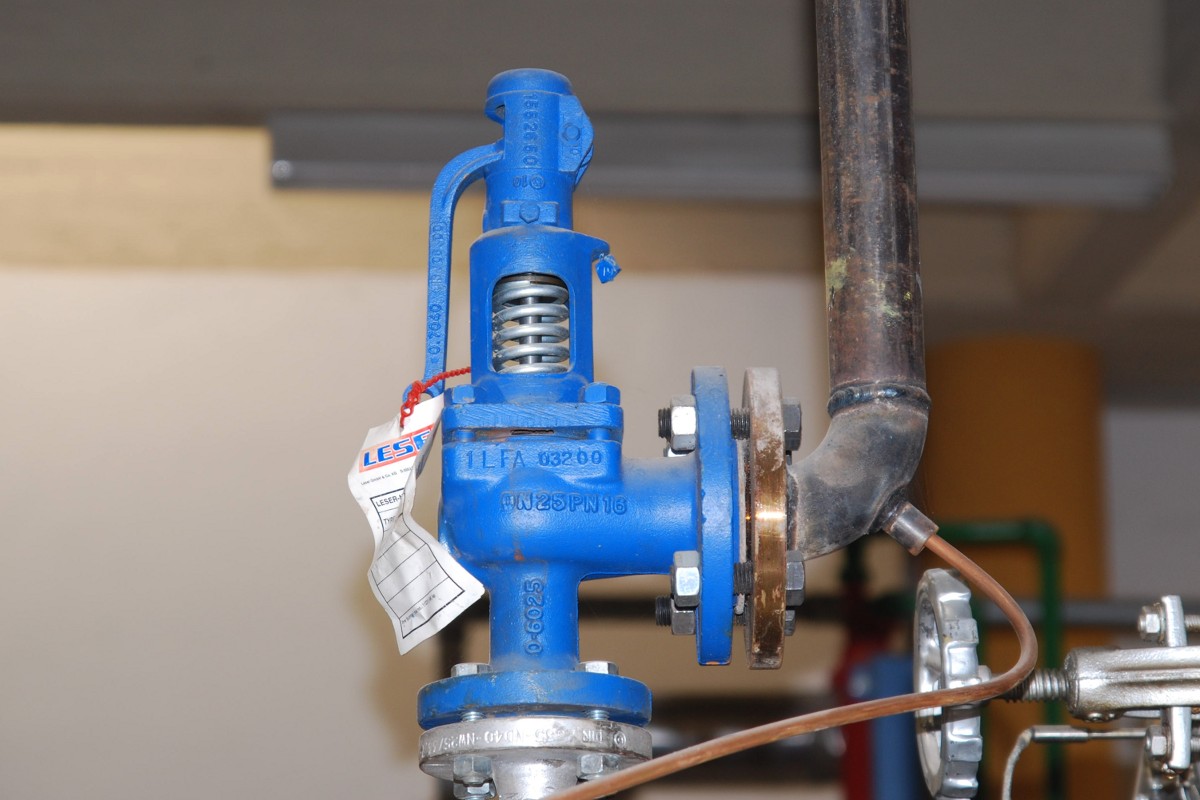

A “safety valve” is an exception to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. A safety valve allows a judge to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum term if certain conditions are met. Safety valves can be broad or narrow, applying to many or few crimes (e.g., drug crimes only) or types of offenders (e.g., nonviolent offenders). They do not repeal or eliminate mandatory minimum sentences. However, safety valves save taxpayers money because they allow courts to give shorter, more appropriate prison sentences to offenders who pose less of a public safety threat. This saves our scarce taxpayer dollars and prison beds for those who are most deserving of the mandatory minimum term and present the biggest danger to society.

The Problem:Under current federal law, there is only one safety valve, and it applies only to first-time, nonviolent drug offenders whose cases did not involve guns. FAMM was instrumental in the passage of this safety valve, in 1994. Since then, more than 95,000 nonviolent drug offenders have received fairer sentences because of it, saving taxpayers billions. But it is a very narrow exception: in FY 2015, only 13 percent of all drug offenders qualified for the exception.

Mere presence of even a lawfully purchased and registered gun in a person’s home or car is enough to disqualify a nonviolent drug offender from the safety valve,

Even very minor prior infractions (e.g., careless driving) that resulted in no prison time can disqualify an otherwise worthy low-level drug offender from the safety valve, and

Other federal mandatory minimum sentences for other types of crimes – notably, gun possession offenses – are often excessive and apply to low-level offenders who could serve less time in prison, at lower costs to taxpayers, without endangering the public.

The Solution:Create a broader safety valve that applies to all mandatory minimum sentences, and expand the existing drug safety valve to cover more low-level offenders.

Congress’s new bipartisan task force on overcriminalization in the justice system held its first hearing earlier this month. It was a timely meeting: national crime rates are at historic lows, yet the federal prison system is operating at close to 40 percent over capacity.

Representative Karen Bass, a California Democrat, asked a panel of experts about the problem of mandatory minimum sentences, which contribute to prison overcrowding and rising costs. In the 16-year period through fiscal 2011, the annual number of federal inmates increased from 37,091 to 76,216, with mandatory minimum sentences a driving factor. Almost half of them are in for drugs.

The problem starts with federal drug laws that focus heavily on the type and quantity of drugs involved in a crime rather than the role the defendant played. Federal prosecutors then seek mandatory sentences against defendants who are not leaders and managers of drug enterprises. The result is that 93 percent of those convicted of drug trafficking are low-level offenders.

Both the Senate and the House are considering a bipartisan bill to allow federal judges more flexibility in sentencing in the 195 federal crimes that carry mandatory minimums. The bill, called the Justice Safety Valve Act, deserves committee hearings and passage soon.

:format(jpeg)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/46063598/455040032__1_.0.0.jpg)

For years, Congress had attempted to pass criminal justice reform legislation, such as the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act (SRCA) introduced in 2015 by Senators Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Dick Durbin (D-Ill.). But the SRCA failed to pass in 2016 despite overwhelming bipartisan support, thanks to opposition from Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) and then-Senator Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.).

That all changed last December when the Senate finally passed, and President Trump signed, the FIRST STEP Act — a modest bill that, despite some initial setbacks, includes key parts of the SRCA. That makes it the first major reduction to federal drug sentences.

The Brennan Center has been advocating for federal sentencing reform for years: Attorneys at the Center’s Justice Program were heavily involved in the fight to pass the SRCA and its predecessor, the Smarter Sentencing Act of 2013.

But when Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, many worried that sentencing reform would prove impossible for the next four years. Trump’s position on criminal justice reform was unclear at best and regressive at worse. His early moves appeared to confirm these suspicions: While still President-Elect, Trump nominated Jeff Sessions, a vocal critic of any reduction to the U.S. prison population, to be the nation’s chief law enforcement officer. Nonetheless, Grassley and Durbin reintroduced the SRCA again in October 2017 and navigated it through committee in early 2018. The bill looked poised to stall once again due to vocal opposition from Sessions.

But the momentum started to pick up in early 2018, when the White House brokered the Prison Reform and Redemption Act, a bipartisan bill aimed at improving conditions in federal prisons. This bill, which was renamed the FIRST STEP Act after some modest improvements were added, still lacked any meaningful sentencing reform component, meaning it would have done little to reduce the prison population. For the White House, that was part of the appeal: Republican leaders believed that SRCA’s sentencing reform provisions made it a nonstarter among conservatives. But because of that, the Brennan Center and a coalition of more than 100 civil rights groups opposed the bill, arguing that the votes were there for sentencing reform — if only Republican leaders would put a bill on the floor. Nonetheless, the FIRST STEP Act passed the House of Representatives by a wide margin of 360 to 59.

That’s where the process stood until late last year. A breakthrough occurred in November, when lawmakers and advocates reached a compromise on the FIRST STEP Act, amending it to incorporate four provisions from the SRCA. The measure garnered the support of the president and both Republicans and Democrats in Congress. Critically, the compromise was blessed by Grassley and Durbin, signaling that the new bill adequately met the goals of their own prior bill.

The FIRST STEP Act initially stalled in the Senate amid opposition from a right-wing minority faction led again by Cotton. And, critically, time was running out in the legislative session, making Republican leaders balk at spending precious floor time on the bill. But another series of compromises quieted opposition from Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) and garnered support for the bill from Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), the majority whip, clearing the path for an easy floor vote. After that change and continued pressure from Trump, Grassley, the Koch Brothers, and constituents in Kentucky, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced in mid-December that he would bring up the bill for a vote before the end of the year, during the lame-duck Congress.

Longtime opponents of reform like Cotton still had a chance to block the bill: They could run out the clock. But a series of procedural shortcuts allowed McConnell to bring the bill to the floor by essentially slotting the text of the bill into another piece of legislation that was already eligible for Senate consideration. And so another hurdle was cleared.

But one more remained. During the amendment process for the FIRST STEP Act, Cotton and Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.) pushed for a series of “poison pill” amendments that would have unacceptably weakened the bill and split the bipartisan coalition supporting it, just at the moment of passage. But those amendments ultimately failed to materialize in the final bill, which cleared the Senate by an overwhelming 87–12 margin. Not a single Democrat voted against the bill, and Republican opponents of reform were relegated to a small minority. Next, then-House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) cleared the way for quick consideration of the bill in the House of Representatives — and sent it to President Trump’s desk just before Christmas. The president signed the bill on December 21.

The FIRST STEP Act is consequential because it includes provisions for meaningful sentencing reform, which would reduce the number and amount of people in prison and is part of the starting point of any serious legislation for criminal justice reform. Sentencing laws played a central role in the rise of mass incarceration in recent decades. The federal prison population, in particular, has risen by more than 700 percent since 1980, and federal prison spending has increased by nearly 600 percent. That growth has disproportionally affected Black, Latino, and Native Americans.

Federal mandatory minimum sentences were a catalyst for the recent surge of unnecessarily harsh prison sentences. More than two-thirds of federal prisoners serving a life sentence or a virtual life sentence have been convicted of non-violent crimes.

But research continues to show that long prison sentences are often ineffective. One Brennan Center study found that overly harsh sentences have done little to reduce crime. In fact, in some cases, longer prison stays can actually increase the likelihood of people returning to criminal activity. These sentences disproportionately impact people of color and low-income communities.

The FIRST STEP Act shortens mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenses. It also eases a federal “three strikes” rule — which currently imposes a life sentence for three or more convictions — and issues a 25-year sentence instead. Most consequentially, it expands the “drug safety-valve,” which would give judges more discretion to deviate from mandatory minimums when sentencing for nonviolent drug offenses.

In an overdue change, the bill also makes the Fair Sentencing Act retroactive. Passed in 2010, the Fair Sentencing Act has helped reduce the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine offenses — a disparity that has hurt racial minorities. The FIRST STEP Act will now apply the Fair Sentencing Act to 3,000 people who were convicted of crack offenses before the law went into effect.

Beyond sentencing reform, the FIRST STEP Act includes provisions that will improve conditions for current prisoners and address several laws that increased racial disparities in the federal prison system. The bill will require federal prisons to offer programs to reduce recidivism; ban the shackling of pregnant women; and expand the cap on “good time credit” — or small sentence reductions based on good behavior — from around 47 to 54 days per year. That “good time” amendment will benefit as many 85 percent of federal prisoners.

The FIRST STEP Act is a critical win in the fight to reduce mass incarceration. While the bill is hardly a panacea, it’s the largest step the federal government has taken to reduce the number of people in federal custody. (The federal government remains the nation’s leading incarcerator, and more people are under the custody of the federal Bureau of Prisons than any single state system.)

The FIRST STEP Act’s overwhelming passage demonstrates that the bipartisan movement to reduce mass incarceration remains strong. And the bill, which retains major parts of SRCA’s sentencing reform provisions, is now known as “Trump’s criminal justice bill.” This means that conservatives seeking to curry favor with the president can openly follow his example or push for even bolder reforms. Finally, this dynamic creates a unique opening for Democrats vying for the White House in 2020 to offer even better solutions to end mass incarceration.

The FIRST STEP Act marks progress for criminal justice reform, but it has some notable shortcomings. It will leave significant mandatory minimum sentences in place. In addition, two of the bill’s key sentencing provisions are not retroactive, which minimizes their overall impact.

“It’s imperative that this first step not be the only step,” said Inimai Chettiar, director of the Brennan Center’s Justice Program. “Now we must focus our efforts on bigger and bolder widespread reforms that will make our system more fair and more humane. We know better, and we must do better.”

One step is to eliminate incarceration for lower-level crimes, such as minor marijuana trafficking and immigration crimes. The default sentences for those crimes should be alternatives to incarceration, such as treatment, community service, or probation. Second, lawmakers should also pass legislation that would make default prison sentences — which are often excessively long — proportional to the specific crimes committed. If Congress and every state enacted this pair of reforms, the national prison population would be safely reduced by 40 percent. Third, Congress can use the power of the purse to encourage these changes. Washington spends a significant amount of money supporting state criminal justice systems: Those dollars could be used to reward policies that reduce rather than entrench mass incarceration.

Ultimately, the FIRST STEP Act is one step in the right direction for reducing mass incarceration in the United States. It has elevated criminal justice reform as a rare space for bipartisan consensus and cooperation in a fractured national political environment. With an awareness of that consensus, we should push for the bigger next steps that will move us toward ending mass incarceration.

Today, the U.S. has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world. With over 2.3 million men and women living behind bars,our imprisonment rate is the highest it’s ever been in U.S. history. And yet, our criminal justice system has failed on every count: public safety, fairness and cost-effectiveness. Across the country, the criminal justice reform conversation is heating up. Each week, we feature our some of the most exciting and relevant news in overincarceration discourse that we’ve spotted from the previous week. Check back weekly for our top picks.

State Legislative Highlights:A number of states have either passed laws or are advancing bills that could reduce state correctional populations. You can find a summary of those bills on our blog; below are some of the highlights:

Florida‘s HB 159 and SB 420 each passed their subcommittees; the bills would allow judges to depart from mandatory minimum sentences for certain defendants charged with drug offenses.

Georgia‘s legislature passed comprehensive juvenile justice reform, HB 242. Gov. Deal is expected to sign the bill. The bill could reduce the number of youth in jail or prison by one-third over the next five years.

Hawaii‘s Senate unanimously passed SB 472, which would decriminalize possession of one ounce or less of marijuana, and the House reduced the fine by amendment. The Senate also unanimously passed SB 68, which would allow judges to impose a sentence below the mandatory minimum for most drug offenses. Also on the table is HB 255, which would allow prisons to release elderly persons if they suffer from debilitating illness and pose a low risk to public safety.

Indiana‘s House passed a criminal code revision bill that has some good elements but may ultimately increase the state’s prison population significantly. HB 1006 would create a felony threshold for theft, reduce sentences for low-level drug offenses, reduce the “school zone” for drug-offense enhancements from 1000 to 500 feet, limit the application of the habitual offender statute, and expand judges’ discretion to suspend sentences. But the bill also increases sentence lengths for some violent and sex offenses, and the Department of Corrections projects that the longer sentences will nearly double the state’s prison population in 20 years, although that estimate is challenged by another analysis. The House also passed HB 1482, which would increase the list of convictions eligible for expungement.

Louisianais considering HB 103, which would remove marijuana possession from mandatory minimum sentences under the state’s habitual offender law, which can result in a life sentence for marijuana offenses alone. Gov. Jindal also announced his support for upcoming bills to reduce juvenile incarceration, expand the state’s drug courts, and allow for early release of prisoners convicted of drug offenses.

Massachusetts is considering S. 667, which would repeal mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenses, as well as H. 1645, which would reduce the “school zone” area within which drug offenses carry stiffer sentences.

Missouriis considering HB 210, a rewrite of the criminal code that includes sentencing reform, such as raising the felony theft threshold, reducing some drug penalties and reducing the “school zone” for drug-offense enhancements.

New Mexico‘s House passed HB 465, which would decriminalize possession of one ounce or less of marijuana, although the governor of New Mexico has threatened a veto if the bill passes the senate.

Oklahoma‘s House passed HB 1056, to allow elderly prisoners who pose a low public safety risk to apply for conditional parole. As many as 2,000 prisoners could be eligible.

Rhode Island is considering S. 0341, which would reduce the penalties for some minor offenses, such as shoplifting, disorderly conduct, and driving with a suspended license.

Texasis considering several reform bills, including SB 90, which would expand community treatment for drug possession, and HB 1069, which would reclassify certain minor offenses as misdemeanors. For more, see The Texas Criminal Justice Coalition’s list of bills to safely reduce incarceration in Texas.

Vermont‘s Senate passed S. 1, which would require judges to consider the financial cost of available sentences if the defendant is charged with a nonviolent offense. Also in the House is H. 200, which would decriminalize possession of up to two ounces of marijuana.

West Virginia‘s Senate unanimously passed SB 371, which emphasizes increased community supervision of probationers and parolees, discourages revocation for technical violations, and introduces risk assessment mechanisms that would enable, but not require, judges to make better informed decisions. Advocates are now working with members of the House to amend the bill to ensure that it will cause a meaningful reduction in the state’s prison population.

Senators Leahy and Paul Introduce Mandatory Minimum Reform Bill:This month, senators from both parties introduced a bill that would allow judges to impose a sentence below the mandatory minimum for any federal offense. The Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013 would give judges greater flexibility; they would not be forced to administer needlessly long sentences for certain offenders. To learn more, read our blog, as well as this primer on the bill and FAQ sheet from Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

Towns Don’t Need Tanks. ACLU Launches Investigation into Police Militarization:American neighborhoods are increasingly being policed by cops armed with the weapons and tactics of war, but very little is is known about exactly how many police departments have military weapons and training, how militarized the police have become, and how extensively federal money is incentivizing this trend. To understand the true scope of the militarization of policing in America, ACLU affiliates in 25 states filed over 255 public records requests with law enforcement agencies and National Guard offices to determine the extent to which federal funding and support has fueled the militarization of state and local police departments. For more:

The Sad State of Indigent Defense 50 Years after Gideon v. Wainwright:March 18 was the 50th Anniversary of Gideon, in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that poor defendants in criminal cases have a constitutional right to legal counsel even if they cannot afford it. But a half a century later, this promise remains woefully unfulfilled. In the coming year, the ACLU will share stories that illustrate the current state of indigent defense on our website, such as this one from Memphis, Tennessee. For more, see these important resources and commentary on the state of indigent defense at Gideon‘s golden anniversary:

ACLU Works to Reduce the Imprisonment of Immigrants in Ongoing Reform Debate:The current debate about immigration reform implicates a large and growing part of our federal prisons. Almost 1 out of 10 federal prisoners is convicted of entering the country illegally—now the most commonly charged federal offense. Historically, many immigrants accused of crossing the border without authorization were simply returned to their countries of origin; today, they are being sent in record numbers to languish in privatized federal prisons under “zero-tolerance” prosecution programs such as Operation Streamline. To learn more about how the ACLU is opposing the incarceration of immigrants who pose no threat to public safety, read this op-ed in The Hill by Vicki Gaubeca and retired federal magistrate judge James Stiven, as well as our recent statement to a Senate committee addressing civil immigration prisons.

NBC’s Rock Center Looks at Solitary Confinement of Youth: The ACLU’s Ian Kysel was interviewed for a recent segment about youth solitary confinement on Rock Center. Read Ian’s blog about the interview.

ACLU of Maine Shares Blueprint for Successful Reform: Since 2009, Maine has reduced its solitary confinement population by over 70 percent. Maine’s reforms were the result of a seven-year effort that is documented in a new report from the ACLU of Maine, Change Is Possible: A Case Study of Solitary Confinement Reform in Maine. In addition to reading the report, read this blog post and visit the report’s home page.

ACLU Testifies to Human Rights Commission on Harms of Solitary Confinement: This month, the ACLU urged the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to review the use of solitary confinement in the United States. Read more about the hearing at our blog, along with our testimony, and the testimony we submitted with Human Rights Watch on the solitary confinement of young people.

In 2013 Senators Richard Durbin (D-IL), Patrick Leahy (D-VT), and Mike Lee (R-UT) introduced the Smarter Sentencing Act to decrease mandatory minimum sentences for federal drug crimes and enlarge the existing safety valve for federal drug offenses.1 The Smarter Sentencing Act reduces the statutory minimum sentence of specific federal drug offenses and permits judges to deviate from mandatory minimum sentences for controlled sub- stance offenses under certain circumstances.2 Similarly in 2013, Senators Leahy and Rand Paul (R-KY), as well as Representatives Bobby Scott (D-VA) and Thomas Massie (R-KY), introduced the Justice Safety Valve Act.3 The Justice Safety Valve Act would give judges more discretion in sentencing by permitting judges to sentence offenders below the mandatory minimum sentence when such sentence would not meet one of the requisite goals of punishment.4 Both acts aim to deter crime through more efficient means while reducing federal prison expenditure and the federal inmate population.

8613371530291

8613371530291