north american safety valve kansas city made in china

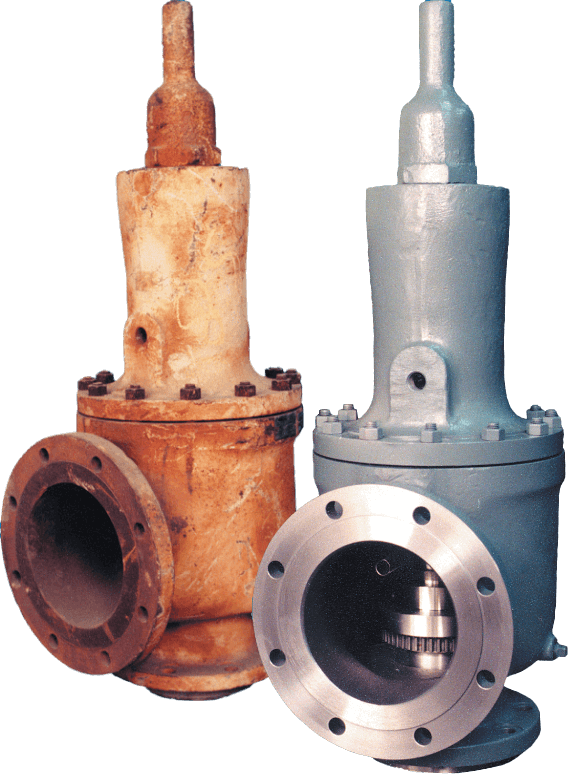

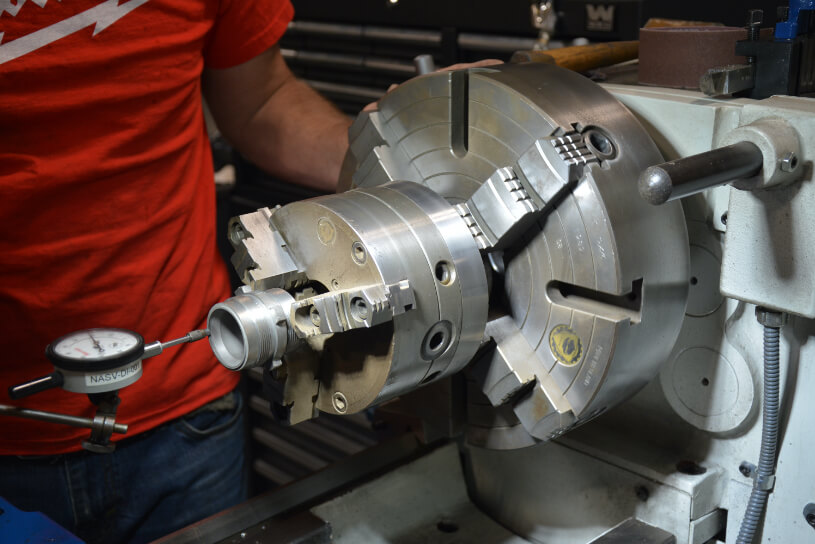

Of all the challenges you face keeping your customers’ plants operating at full capacity, safety and relief valves shouldn’t be one of them. NASVI’s job is to give you the confidence that your valve supply chain is rock solid regardless the pressure it’s under.

AfghanistanAlbaniaAlgeriaAmerican SamoaAndorraAngolaAnguillaAntarcticaAntigua and BarbudaArgentinaArmeniaArubaAustraliaAustriaAzerbaijanBahamasBahrainBangladeshBarbadosBelarusBelgiumBelizeBeninBermudaBhutanBoliviaBonaire, Sint Eustatius and SabaBosnia and HerzegovinaBotswanaBouvet IslandBrazilBritish Indian Ocean TerritoryBrunei DarussalamBulgariaBurkina FasoBurundiCabo VerdeCambodiaCameroonCanadaCayman IslandsCentral African RepublicChadChileChinaChristmas IslandCocos IslandsColombiaComorosCongoCongo, Democratic Republic of theCook IslandsCosta RicaCroatiaCubaCuraçaoCyprusCzechiaCôte d"IvoireDenmarkDjiboutiDominicaDominican RepublicEcuadorEgyptEl SalvadorEquatorial GuineaEritreaEstoniaEswatiniEthiopiaFalkland IslandsFaroe IslandsFijiFinlandFranceFrench GuianaFrench PolynesiaFrench Southern TerritoriesGabonGambiaGeorgiaGermanyGhanaGibraltarGreeceGreenlandGrenadaGuadeloupeGuamGuatemalaGuernseyGuineaGuinea-BissauGuyanaHaitiHeard Island and McDonald IslandsHoly SeeHondurasHong KongHungaryIcelandIndiaIndonesiaIranIraqIrelandIsle of ManIsraelItalyJamaicaJapanJerseyJordanKazakhstanKenyaKiribatiKorea, Democratic People"s Republic ofKorea, Republic ofKuwaitKyrgyzstanLao People"s Democratic RepublicLatviaLebanonLesothoLiberiaLibyaLiechtensteinLithuaniaLuxembourgMacaoMadagascarMalawiMalaysiaMaldivesMaliMaltaMarshall IslandsMartiniqueMauritaniaMauritiusMayotteMexicoMicronesiaMoldovaMonacoMongoliaMontenegroMontserratMoroccoMozambiqueMyanmarNamibiaNauruNepalNetherlandsNew CaledoniaNew ZealandNicaraguaNigerNigeriaNiueNorfolk IslandNorth MacedoniaNorthern Mariana IslandsNorwayOmanPakistanPalauPalestine, State ofPanamaPapua New GuineaParaguayPeruPhilippinesPitcairnPolandPortugalPuerto RicoQatarRomaniaRussian FederationRwandaRéunionSaint BarthélemySaint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da CunhaSaint Kitts and NevisSaint LuciaSaint MartinSaint Pierre and MiquelonSaint Vincent and the GrenadinesSamoaSan MarinoSao Tome and PrincipeSaudi ArabiaSenegalSerbiaSeychellesSierra LeoneSingaporeSint MaartenSlovakiaSloveniaSolomon IslandsSomaliaSouth AfricaSouth Georgia and the South Sandwich IslandsSouth SudanSpainSri LankaSudanSurinameSvalbard and Jan MayenSwedenSwitzerlandSyria Arab RepublicTaiwanTajikistanTanzania, the United Republic ofThailandTimor-LesteTogoTokelauTongaTrinidad and TobagoTunisiaTurkmenistanTurks and Caicos IslandsTuvaluTürkiyeUS Minor Outlying IslandsUgandaUkraineUnited Arab EmiratesUnited KingdomUnited StatesUruguayUzbekistanVanuatuVenezuelaViet NamVirgin Islands, BritishVirgin Islands, U.S.Wallis and FutunaWestern SaharaYemenZambiaZimbabweÅland Islands

NASVI’s 35,000 safety valves in stock in our 100,000 sq. ft. facility means nothing without the people who know every detail about every valve, manufacturer and operations. Combined, our people have well over a century of industry knowledge. And, it’s just a call or email away.

We keep businesses running with a vast, constantly improving and evolving selection of products. We understand that our customers cannot afford downtime or environmental and safety risks. That is why we only provide quality and reliable products from the most reputable manufacturers.

In 2020, the overall unemployment rate (jobless rate) for the United States averaged 8.1 percent. However, the rate varied across race and ethnicity groups. Among the race groups, jobless rates were higher than the national rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives (11.7 percent), people categorized as being of Two or More Races (11.6 percent), and Blacks or African Americans (11.4 percent). For the year as a whole, the unemployment rates for Asians (8.7 percent) and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders (8.9 percent) were not much different from the overall unemployment rate. The jobless rate was lower than the national rate for Whites (7.3 percent). The rate for people of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, at 10.4 percent, was higher than the rate of 7.5 percent for non-Hispanics. (See table 1 and 2.)

The labor market downturn in 2020 reflected the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and efforts to contain it. The effects of the pandemic on the job market, while widespread, varied across race and ethnicity groups. For example, Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics were disproportionally affected by the pandemic-induced recession in the spring of 2020, in part reflecting their overrepresentation in some of the hardest hit sectors of the economy.

This report describes the labor force characteristics and earnings patterns among the largest race and ethnicity groups living in the United States—Whites, Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics—and provides detailed data through a set of supporting tables. The report also contains a limited amount of data on American Indians and Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders, people who are of Two or More Races, detailed Asian groups, and detailed Hispanic groups. Because of their relatively small sample sizes, estimates for these additional groups are not included in all tables.

By race, Whites made up the majority of the labor force (77 percent). Blacks and Asians constituted an additional 13 percent and 6 percent, respectively. American Indians and Alaska Natives made up 1 percent of the labor force, while Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders accounted for less than half a percent. People of Two or More Races made up 2 percent of the labor force. (See table 1.)

People of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, who may be of any race, made up 18 percent of the total labor force. Almost 9 in 10 Hispanics in the labor force were White (89 percent). Another 5 percent were Black, and 1 percent were Asian. By detailed ethnicity, the majority of Hispanics in the labor force were Mexican (60 percent). Central Americans made up another 11 percent, about two-fifths of whom were Salvadorans. Nine percent of Hispanics in the labor force were Puerto Rican, and 8 percent were South American. People of Cuban and Dominican ethnicity each represented 4 percent of the Hispanic labor force. An additional 5 percent were classified as Other Hispanic or Latino. (See table 2.)

Among the race and ethnicity groups, the percentage of the population either employed or unemployed—the labor force participation rate—was highest for Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders (66.7 percent in 2020), Hispanics (65.6 percent), and people of Two or More Races (64.4 percent). The participation rate for Asians was 62.7 percent; Whites, 61.8 percent; Blacks, 60.5 percent; and American Indians and Alaska Natives, 59.3 percent. (See tables 1, 2, 3, 4, and 4A, and chart 1.)

Among adult men (20 years and older) in the largest race and ethnicity groups (White, Black, Asian and Hispanic), Hispanics were more likely to engage in labor force activity than were the other groups, with a participation rate of 79.1 percent, and Blacks were the least likely, with a rate of 65.6 percent. The labor force participation rate for Asian adult men (74.0 percent) was higher than the rate for White adult men (70.3 percent). Among adult women, Blacks (60.7 percent) were more likely to participate in the labor force than were Hispanics (58.8 percent), Asians (57.7 percent), and Whites (56.8 percent). Among teenagers (16 to 19 years), Asians (19.2 percent) were less likely to participate in the labor force than were Whites (36.8 percent), Hispanics (32.4 percent), and Blacks (29.8 percent). (See table 3.)

The employment-population ratio (the proportion of the population that is employed) ranged from 52.4 percent for American Indians and Alaska Natives to 60.8 percent for Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders. The employment-population ratio was 58.7 percent for Hispanics, 57.3 percent for Asians, 57.3 percent for Whites, 56.9 percent for individuals of Two or More Races, and 53.6 percent for Blacks. (See tables 1, 2, 3, 5, and 5A.)

Among adult men (20 years and older) in the largest race and ethnicity groups, Hispanics continued to have the highest employment-population ratio (71.8 percent). Black men had the lowest (58.0 percent), also continuing a longstanding employment pattern. The employment-population ratios for Asian adult men and White adult men were 68.3 percent and 65.6 percent, respectively. Among adult women, the ratios showed less variation across the major race and ethnicity groups: 54.4 percent for Blacks, 52.7 percent for Whites, 52.4 percent for Hispanics, and 52.3 percent for Asians. (See table 3.)

Chart 2. Educational attainment of the labor force age 25 and older by race and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2020 annual averagesRace or ethnicityLess than a high school diplomaHigh school graduates, no collegeSome college, no degreeAssociate"s degreeBachelor"s degree and higherWhite625151143

Higher levels of education are generally associated with a greater likelihood of employment, and a lower likelihood of unemployment. For all major race and ethnicity groups, jobless rates for people with a bachelor’s degree and higher were lower than for other levels of educational attainment. (See table 6.)

Individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to be employed in higher paying jobs—such as those in management, professional, and related occupations—than are individuals with less education. Median earnings of people 25 years and older increased with educational attainment across all major race and ethnicity groups. Among full-time wage and salary workers, median usual weekly earnings for Blacks ($1,166) and Hispanics ($1,230) with a bachelor’s degree and higher were lower than for Whites ($1,433) and Asians ($1,650). (These earnings comparisons are on a broad level and do not control for many factors that can be significant in explaining earnings differences.) (See table 17.)

Chart 3. Employed people by occupation, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2020 annual averagesOccupationWhiteBlack or African AmericanAsianHispanic or LatinoProduction, transportation, and material moving11.817.19.216.7

Management, professional, and related43.434.758.225.5Note: People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Data may not sum to 100 percent because of rounding.

Hispanics accounted for 18 percent of total employment but were substantially overrepresented in several detailed occupational categories, including painters and paperhangers (51 percent), maids and housekeeping cleaners (46 percent), and construction laborers (46 percent). Blacks made up 12 percent of all employed workers, but were substantially overrepresented in several detailed occupational categories, including home health aides (37 percent), transit and intercity bus drivers (37 percent), nursing assistants (35 percent), correctional officers and jailers (33 percent), and security guards and gaming surveillance officers (31 percent). Asians accounted for 6 percent of all employed workers but made up a much larger share of workers in several occupational categories, including manicurists and pedicurists (77 percent), software developers (34 percent), computer programmers (28 percent), and financial and investment analysts (21 percent). Whites made up 78 percent of all employed people, and accounted for 96 percent of farmers, ranchers, and other agricultural managers; construction managers (91 percent); and wholesale and manufacturing sales representatives (89 percent). (See table 8.)

Among employed men, Hispanics were more likely to work in the construction industry (20 percent) than were Whites (14 percent), Blacks (7 percent), or Asians (3 percent). Employed Black men were more likely than employed men of other race and ethnicity groups to work in transportation and utilities (14 percent). Twenty-two percent of employed Asian men worked in professional and business services, higher than the shares of White men (14 percent), Black men (12 percent), and Hispanic men (12 percent). Among employed women, Hispanics were more likely to work in leisure and hospitality (12 percent) than were Whites, Blacks, or Asians (8 percent each). A large share of employed women across all race and ethnicity groups worked in education and health services: Blacks (41 percent), Whites (37 percent), Asians (32 percent), and Hispanics (31 percent). (See table 9.)

Across all race and ethnicity groups, fathers living with children under 18 years were much more likely to be in the labor force than were mothers with children under 18 years. Labor force participation rates for these fathers were 93.4 percent for White men, 92.6 percent for Hispanic men, 92.5 percent for Asian men, and 86.0 percent for Black men.

In 2020, the overall unemployment rate for the United States averaged 8.1 percent, but the rate varied across race and ethnicity groups. The unemployment rate averaged 11.7 percent for American Indians and Alaska Natives, 11.6 percent for people of Two or More Races, 11.4 percent for Blacks, 8.9 percent for Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders, 8.7 percent for Asians, and 7.3 percent for Whites. The unemployment rate was 10.4 percent for Hispanics. (See tables 1, 2, 3, 12, and 12A, and charts 4 and 5.)

Chart 5. Unemployment rates by race and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 1973–2020 annual averagesYearBlack or African AmericanWhiteHispanic or LatinoAsian19739.44.37.5–

Among adult men (20 years and older) in the largest race and ethnicity groups, Blacks were the most likely to be jobless (with an unemployment rate of 11.6 percent), while Whites (6.7 percent) were the least likely. The jobless rate for Asian men (7.7 percent) was lower than the rate for Hispanic men (9.2 percent). Among adult women, the unemployment rate for Whites (7.3 percent) was lower than for Asians (9.5 percent), Blacks (10.4 percent), and Hispanics (10.9 percent). Among teenagers (16 to 19 years), Blacks and Hispanics had the highest unemployment rates, at 24.1 percent and 21.2 percent, respectively, compared with 16.6 percent for Whites and 14.9 percent for Asians. (See table 3.)

Of the 12.9 million people unemployed in 2020, 76 percent were job losers (workers who were on temporary layoff, lost their jobs permanently, or who completed temporary jobs). Reentrants to the labor force (15 percent), job leavers (5 percent), and new entrants (4 percent) accounted for the rest of the unemployed. Of the total unemployed for each major race and ethnicity group, about 78 percent of Asians, 77 percent of Whites, and 77 percent of Hispanics were job losers, compared with 71 percent of Blacks. (See table 14.)

Among the major race and ethnicity groups, Hispanics and Blacks continued to have considerably lower earnings than Whites and Asians. The median usual weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers in 2020 were $758 for Hispanics, $794 for Blacks, $1,003 for Whites, and $1,310 for Asians. The earnings for White men ($1,110), Black men ($830), and Hispanic men ($797) were 77 percent, 57 percent, and 55 percent, respectively, of the earnings of Asian men ($1,447). The median earnings of White women ($905), Black women ($764), and Hispanic women ($705) were 79 percent, 67 percent, and 62 percent, respectively, of the earnings of Asian women ($1,143). (These earnings comparisons are on a broad level and do not control for many factors that can be significant in explaining earnings differences, such as job skills and responsibilities, work experience, and specialization.) (See table 16.)

The earnings disparity across the major race and ethnicity groups for men holds for all major occupational groups. For example, median usual weekly earnings of Asian men and White men working full time in management, professional, and related occupations (the highest paying major occupational group), at $1,883 and $1,599, respectively, were considerably higher than the earnings of Hispanic men ($1,316) and Black men ($1,232) in the same occupational group. (See table 18.)

Median weekly earnings for women by race and ethnicity group were relatively close for service occupations: $600 for Asians, $578 for Whites, $551 for Blacks, and $535 for Hispanics. By contrast, in management, professional, and related occupations, the earnings of Asian women were considerably higher than those for women in other race and ethnicity groups.

Table 2. Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population 16 years and older by detailed Asian group, and Hispanic or Latino and non-Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, gender, and race, 2020 annual averages (Numbers in thousands)

Note: Estimates for the above race groups (White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, and Asian non-Hispanic) do not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Table 3. Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population by gender, age, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2020 annual averages (Numbers in thousands)

Note: Estimates for the above race groups (White, Black or African American, and Asian) do not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Note: Beginning in 2003, estimates for White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander race groups include people who selected that race group only; people who selected more than one race group are included in the Two or More Races category. Prior to 2003, people who reported more than one race were included in the group they identified as the main race. Asian estimates for 2000–02 are for Asians and Pacific Islanders; beginning in 2003, Asian is a separate category, as is Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Dash indicates data not available.

Note: Beginning in 2003, estimates for White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander race groups include people who selected that race group only; people who selected more than one race group are included in the Two or More Races category. Prior to 2003, people who reported more than one race were included in the group they identified as the main race. Asian estimates for 2000–02 are for Asians and Pacific Islanders; beginning in 2003, Asian is a separate category, as is Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Dash indicates data not available.

Note: Beginning in 2003, estimates for White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander race groups include people who selected that race group only; people who selected more than one race group are included in the Two or More Races category. Prior to 2003, people who reported more than one race were included in the group they identified as the main race. Asian estimates for 2000–02 are for Asians and Pacific Islanders; beginning in 2003, Asian is a separate category, as is Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Dash indicates data not available.

Note: Beginning in 2003, estimates for White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander race groups include people who selected that race group only; people who selected more than one race group are included in the Two or More Races category. Prior to 2003, people who reported more than one race were included in the group they identified as the main race. Asian estimates for 2000–02 are for Asians and Pacific Islanders; beginning in 2003, Asian is a separate category, as is Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Dash indicates data not available.

Table 6. Employment status of people 25 years and older by educational attainment, gender, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2020 annual averages (Numbers in thousands)

Note: Estimates for the above race groups (White, Black or African American, and Asian) do not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Note: Effective with January 2020 data, occupations reflect the introduction of the 2018 Census occupational classification system, derived from the 2018 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC). No historical data have been revised. Data for 2020 are not strictly comparable with earlier years. Estimates for the above race groups (White, Black or African American, and Asian) do not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Note: Effective with January 2020 data, occupations reflect the introduction of the 2018 Census occupational classification system, derived from the 2018 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC). No historical data have been revised. Data for 2020 are not strictly comparable with earlier years. Estimates for the above race groups (White, Black or African American, and Asian) do not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Dash indicates no data or data that do not meet publication criteria (values not shown where base is less than 50,000).

Note: Estimates for the above race groups (White, Black or African American, and Asian) do not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Table 10. Employment and unemployment in families by type of family, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2020 annual averages (Numbers in thousands)

Note: The race or ethnicity of the family is determined by that of the householder, the family reference person in whose name the housing unit is owned or rented. Estimates for the above race groups (White, Black or African American, and Asian) do not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Table 11. Labor force participation rates by presence and age of youngest child, gender, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 1994–2020 annual averages (Percent)

Note: Beginning in 2003, estimates for White, Black or African American, and Asian race groups include people who selected that race group only; people who selected more than one race group are not included in these groups. Prior to 2003, people who reported more than one race were included in the group they identified as the main race. Asian estimates for 2000–02 are for Asians and Pacific Islanders; beginning in 2003, Asian is a separate category. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Children are "own" children and include sons, daughters, stepchildren, and adopted children. Not included are nieces, nephews, grandchildren, and other related and unrelated children. Dash indicates data not available.

Note: Beginning in 2003, estimates for White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander race groups include people who selected that race group only; people who selected more than one race group are included in the Two or More Races category. Prior to 2003, people who reported more than one race were included in the group they identified as the main race. Asian estimates for 2000–02 are for Asians and Pacific Islanders; beginning in 2003, Asian is a separate category, as is Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Dash indicates data not available.

Note: Beginning in 2003, estimates for White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander race groups include people who selected that race group only; people who selected more than one race group are included in the Two or More Races category. Prior to 2003, people who reported more than one race were included in the group they identified as the main race. Asian estimates for 2000–02 are for Asians and Pacific Islanders; beginning in 2003, Asian is a separate category, as is Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Dash indicates data not available.

Note: Estimates for the above race groups (White, Black or African American, and Asian) do not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Note: Estimates for the above race groups (White, Black or African American, and Asian) do not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Note: Estimates for the above race groups (White, Black or African American, and Asian) do not sum to totals because data are not presented for all races. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Table 16. Median usual weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by gender, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 1979–2020 annual averages

Note: Beginning in 2003, estimates for White, Black or African American, and Asian race groups include people who selected that race group only; people who selected more than one race group are not included in these groups. Prior to 2003, people who reported more than one race were included in the group they identified as the main race. Asian estimates for 2000–02 are for Asians and Pacific Islanders; beginning in 2003, Asian is a separate category. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Dash indicates data not available.

Table 17. Median usual weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by educational attainment, gender, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2020 annual averages

Table 18. Median usual weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by occupation, gender, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2020 annual averages

Note: Effective with January 2020 data, occupations reflect the introduction of the 2018 Census occupational classification system, derived from the 2018 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC). No historical data have been revised. Data for 2020 are not strictly comparable with earlier years. People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Information on occupation and industry applies to the job held during the reference week. People with two or more jobs are classified into the occupation and industry in which they worked the greatest number of hours. Beginning with data in 2020, the occupational and industry classification of CPS data is based on the 2018 Census occupational classification system and the 2017 Census industrial classification system, which are derived from the 2018 Standard Occupation Classification (SOC) and the 2017 North American Industry Classification (NAICS), respectively.

Race is reported by the household respondent. In accordance with Office of Management and Budget standards, White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander are terms used to describe a person’s race. Beginning in 2003, people in these categories are those who selected that race group only. Those who identify multiple race groups are categorized as people of Two or More Races. (Previously, people identified a group as their main race.) People who identified themselves as Asian are further classified as Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, or Other Asian. The Other Asian category includes both individuals of groups not listed—such as Pakistani, Hmong, and Cambodian—and those who reported two or more Asian groups. Estimates for American Indians and Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders, and people of Two or More Races are not shown separately in all tables because the number of survey respondents is too small to develop estimates of publication quality.

Hispanic or Latino ethnicity refers to people who identified themselves in the survey as being of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin. These individuals are further classified by detailed Hispanic ethnicity. The detailed classifications include Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central American, South American, and Dominican and Other Hispanic or Latino. The Central American category includes the two subcategories of Salvadoran and Other Central American (excluding Salvadorans). The Dominican and Other Hispanic or Latino category also includes two subcategories—Dominican, and Other Hispanic or Latino (excluding Dominicans). People whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

A family is a group of two or more people residing together who are related by birth, marriage, or adoption; all such people are considered members of one family. The race or ethnicity of families is determined by that of the householder: the person, or one of the people, in whose name the housing unit is owned or rented. The count of families is for “primary” families only—that is, the householder and all other people related to and residing with the householder. Families comprise those without children as well as those with children under 18 years and are defined as follows:

Headquartered in Calgary, Alberta, the railway owns approximately 20,100 kilometres (12,500 mi) of track in seven provinces of Canada and into the United States,Montreal to Vancouver, and as far north as Edmonton. Its rail networkMinneapolis–St. Paul, Milwaukee, Detroit, Chicago, and Albany, New York, in the United States.

The company acquired two American lines in 2009: the Dakota, Minnesota and Eastern Railroad (DM&E) and the Iowa, Chicago and Eastern Railroad (IC&E). The trackage of the IC&E was at one time part of CP subsidiary Soo Line and predecessor line The Milwaukee Road. The combined DM&E/IC&E system spanned North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Nebraska and Iowa, with two short stretches into Kansas City, Missouri, and Chicago, Illinois. Also, the company owns the Indiana Harbor Belt Railroad, a Hammond, Indiana-based terminal railroad along with Conrail Shared Assets Operations. CP"s ownership of that railroad traces back to the Soo Line"s ownership, inherited from the Milwaukee Road.

As of early 2022Kansas City Southern Railway. If approved by the US Surface Transportation Board, the combined Canadian Pacific Kansas City Limited will form the first and only railroad serving the three biggest countries in North America (Canada, Mexico and the United States).

Together with the Canadian Confederation, the creation of the Canadian Pacific Railway was a task originally undertaken as the National Dream by the Conservative government of Prime Minister John A. Macdonald (1st Canadian Ministry).Alexander Tilloch Galt, who was the owner of the North Western Coal and Navigation Company. British Columbia, a four-month sea voyage away from the East Coast, had insisted upon a land transport link to the East as a condition for joining Confederation (initially requesting a wagon road).

In 1873, John A. Macdonald and other high-ranking politicians, bribed in the Pacific Scandal, granted federal contracts to Hugh Allan"s Canada Pacific Railway Company (which was unrelated to the current company) rather than to David Lewis Macpherson"s Inter-Ocean Railway Company which was thought to have connections to the American Northern Pacific Railway Company. Because of this scandal, the Conservative Party was removed from office in 1873. The new Liberal prime minister, Alexander Mackenzie, ordered construction of segments of the railway as a public enterprise under the supervision of the Department of Public Works led by Sandford Fleming. Surveying was carried out during the first years of a number of alternative routes in this virgin territory followed by construction of a telegraph along the lines that had been agreed upon.Thunder Bay section linking Lake Superior to Winnipeg was commenced in 1875. By 1880, around 1,000 kilometres (700 mi) was nearly complete, mainly across the troublesome Canadian Shield terrain, with trains running on only 500 kilometres (300 mi) of track.

Building the railway took over four years. James J. Hill in 1881 sent Alpheus Beede Stickney to be construction superintendent for the Canadian Pacific Railway. The Canadian Pacific Railway began its westward expansion from Bonfield, Ontario (previously called Callander Station), where the first spike was driven into a sunken railway tie. Bonfield was inducted into Canadian Railway Hall of Fame in 2002 as the CPR first spike location. That was the point where the Canada Central Railway extension ended.Ottawa River passing through places like Cobden, Deux-Rivières and eventually to Mattawa at the confluence of the Mattawa and Ottawa rivers. It then proceeded cross-country towards its final destination of Bonfield. Duncan McIntyre and his contractor James Worthington piloted the CPR expansion. Worthington continued on as the construction superintendent for the CPR past Bonfield. He remained with the CPR for about a year after which he left the company. McIntyre was uncle to John Ferguson who staked out future North Bay and who became the town"s wealthiest inhabitant and mayor for four successive terms.

It was presumed that the railway would travel through the rich "Fertile Belt" of the North Saskatchewan River Valley and cross the Rocky Mountains via the Yellowhead Pass, a route suggested by Fleming based on a decade of work. However, the CPR quickly discarded this plan in favour of a more southerly route across the arid Palliser"s Triangle in Saskatchewan and via Kicking Horse Pass and down the Field Hill to the Rocky Mountain Trench. This route was more direct and closer to the Canada–US border, making it easier for the CPR to keep American railways from encroaching on the Canadian market. However, this route also had several disadvantages.

The greatest disadvantage of the route was in Kicking Horse Pass, at the Alberta-British Columbia border on the continental divide. In the first 6 km (3.7 mi) west of the 1,625 metres (5,331 feet) high summit, the Kicking Horse River drops 350 metres (1,150 feet). The steep drop would force the cash-strapped CPR to build a 7 km (4.3 mi) long stretch of track with a very steep 41⁄2 percent gradient once it reached the pass in 1884. This was over four times the maximum gradient recommended for railways of this era, and even modern railways rarely exceed a two-percent gradient. However, this route was far more direct than one through the Yellowhead Pass and saved hours for both passengers and freight. This section of track was the CPR"s Big Hill. Safety switches were installed at several points, the speed limit for descending trains was set at 10 km per hour (6 mph), and special locomotives were ordered. Despite these measures, several serious runaways still occurred including the first locomotive, which belonged to the contractors, to descend the line. CPR officials insisted that this was a temporary expediency, but this state of affairs would last for 25 years until the completion of the Spiral Tunnels in the early 20th century.

In 1881, construction progressed at a pace too slow for the railway"s officials who, in 1882, hired the renowned railway executive William Cornelius Van Horne to oversee construction with the inducement of a generous salary and the intriguing challenge of handling such a difficult railway project. Van Horne stated that he would have 800 km (500 mi) of main line built in 1882. Floods delayed the start of the construction season, but over 672 km (418 mi) of main line, as well as sidings and branch lines, were built that year. The Thunder Bay branch (west from Fort William) was completed in June 1882 by the Department of Railways and Canals and turned over to the company in May 1883, permitting all-Canadian lake and railway traffic from Eastern Canada to Winnipeg for the first time. By the end of 1883, the railway had reached the Rocky Mountains, just eight kilometres (five miles) east of Kicking Horse Pass. The construction seasons of 1884 and 1885 would be spent in the mountains of British Columbia and on the north shore of Lake Superior.

In March 1885, the North-West Rebellion broke out in the District of Saskatchewan. Van Horne, in Ottawa at the time, suggested to the government that the CPR could transport troops to Qu"Appelle, Assiniboia, in 10 days. Some sections of track were incomplete or had not been used before, but the trip to Winnipeg was made in nine days and the rebellion quickly suppressed. Perhaps because the government was grateful for this service, they subsequently reorganized the CPR"s debt and provided a further $5 million loan. This money was desperately needed by the CPR. However, this government loan later became controversial. Even with Van Horne"s support with moving troops to Qu"Appelle, the government still delayed in giving its support to CPR. This was due to Macdonald putting pressure on George Stephen for additional benefits. Stephen himself later did admit to spending $1 million between 1881 and 1886 to ensure government support. This money went to buying a £40,000 necklace for Lady MacDonald and numerous other "bonifications" to government members.

Meanwhile, in Eastern Canada, the CPR had created a network of lines reaching from Quebec City to St. Thomas, Ontario, by 1885 – mainly by buying the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa & Occidental Railway from the Quebec government and by creating a new railway company, the Ontario and Quebec Railway (O&Q). It also launched a fleet of Great Lakes ships to link its terminals. Through the O&Q, the CPR had effected purchases and long-term leases of several railways, and built a line between Perth, Ontario, and Toronto (completed on 5 May 1884) to connect these acquisitions. The CPR obtained a 999-year lease on the O&Q on 4 January 1884. In 1895, it acquired a minority interest in the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway, giving it a link to New York and the Northeast United States.

By that time, however, the CPR had decided to move its western terminus from Port Moody to Granville, which was renamed "Vancouver" later that year. The first official train destined for Vancouver arrived on 23 May 1887, although the line had already been in use for three months. The CPR quickly became profitable, and all loans from the Federal government were repaid years ahead of time. In 1888, a branch line was opened between Sudbury and Sault Ste. Marie where the CPR connected with the American railway system and its own steamships. That same year, work was started on a line from London, Ontario, to the Canada–US border at Windsor, Ontario. That line opened on 12 June 1890.

The CPR also leased the New Brunswick Railway in 1891 for 991 years,International Railway of Maine, connecting Montreal with Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1889. The connection with Saint John on the Atlantic coast made the CPR the first truly transcontinental railway company in Canada and permitted trans-Atlantic cargo and passenger services to continue year-round when sea ice in the Gulf of St. Lawrence closed the port of Montreal during the winter months. By 1896, competition with the Great Northern Railway for traffic in southern British Columbia forced the CPR to construct a second line across the province, south of the original line. Van Horne, now president of the CPR, asked for government aid, and the government agreed to provide around $3.6 million to construct a railway from Lethbridge, Alberta, through Crowsnest Pass to the south shore of Kootenay Lake, in exchange for the CPR agreeing to reduce freight rates in perpetuity for key commodities shipped in Western Canada.

During the late 19th century, the railway undertook an ambitious programme of hotel construction, building Glacier House in Glacier National Park, Mount Stephen House at Field, British Columbia, the Château Frontenac in Quebec City and the Banff Springs Hotel. By then, the CPR had competition from three other transcontinental lines, all of them money-losers. In 1919, these lines were consolidated, along with the track of the old Intercolonial Railway and its spurs, into the government-owned Canadian National Railways. The CPR suffered its greatest loss of life when one of its steamships, the Norwegian collier Empress (operated by the CPR"s Canadian Pacific Steamship Company) went down in the St. Lawrence River with the loss of 1,024 lives, of which 840 were passengers.

One highlight of the late 1930s, both for the railway and for Canada, was the visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth during their 1939 royal tour of Canada, the first time that the reigning monarch had visited the country. The CPR and the CNR shared the honours of pulling the royal train across the country, with the CPR undertaking the westbound journey from Quebec City to Vancouver. Later that year, the Second World War began. As it had done in World War I, the CPR devoted much of its resources to the war effort. It retooled its Angus Shops in Montreal to produce Valentine tanks and other armoured vehicles, and transported troops and resources across the country. As well, 22 of the CPR"s ships went to war, 12 of which were sunk.

After the Second World War, the transportation industry in Canada changed. Where railways had previously provided almost universal freight and passenger services, cars, trucks and airplanes started to take traffic away from railways. This naturally helped the CPR"s air and trucking operations, and the railway"s freight operations continued to thrive hauling resource traffic and bulk commodities. However, passenger trains quickly became unprofitable. During the 1950s, the railway introduced new innovations in passenger service. In 1955, it introduced The Canadian. For the next eight years, it continued to apply to discontinue the service, and service on The Canadian declined markedly. On 29 October 1978, CP Rail transferred its passenger services to Via Rail, a new federal Crown corporation that is responsible for managing all intercity passenger service formerly handled by both CP Rail and CN. Via eventually took almost all of its passenger trains, including The Canadian, off CP"s lines.

In 1984, CP Rail commenced construction of the Mount Macdonald Tunnel to augment the Connaught Tunnel under the Selkirk Mountains. The first revenue train passed through the tunnel in 1988. At 14.7 km (nine miles), it is the longest tunnel in the Americas. During the 1980s, the Soo Line Railroad, in which CP Rail still owned a controlling interest, underwent several changes. It acquired the Minneapolis, Northfield and Southern Railway in 1982. Then on 21 February 1985, the Soo Line obtained a controlling interest in the bankrupt Milwaukee Road, merging it into its system on 1 January 1986. Also in 1980, Canadian Pacific bought out the controlling interests of the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway (TH&B) from Conrail and molded it into the Canadian Pacific System, dissolving the TH&B"s name from the books in 1985. In 1987, most of CPR"s trackage in the Great Lakes region, including much of the original Soo Line, were spun off into a new railway, the Wisconsin Central, which was subsequently purchased by CN. Influenced by the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1989, which liberalized trade between the two nations, the CPR"s expansion continued during the early 1990s: CP Rail gained full control of the Soo Line in 1990, and bought the Delaware and Hudson Railway in 1991. These two acquisitions gave CP Rail routes to the major American cities of Chicago (via the Soo Line and Milwaukee Road as part of its historically logical route) and New York City (via the D&H).

A new subsidiary company, the St. Lawrence and Hudson Railway, was created to operate its money-losing lines in eastern North America, covering Quebec, Southern and Eastern Ontario, trackage rights to Chicago, Illinois, (on Norfolk Southern lines from Detroit) as well as the Delaware and Hudson Railway in the northeastern United States. However, the new subsidiary, threatened with being sold off and free to innovate, quickly spun off money-losing track to short lines, instituted scheduled freight service, and produced an unexpected turn-around in profitability. On 1 January 2001 the StL&H was formally amalgamated with the CP Rail system.

In 2015–16 Canadian Pacific sought to merge with American railway Norfolk Southern.U.S. Department of Justice over antitrust concerns created by the proposed merger. Canadian Pacific filed a complaint against the U.S. DOJ and dropped their proposed proxy fight in the proposed merger with Norfolk Southern.United Parcel Service (UPS), who spoke out about the rail merger and said they were against the Canadian Pacific/Norfolk Southern merger.

On 4 February 2019, a loaded grain train ran away from the siding at Partridge just above the Upper Spiral Tunnel in Kicking Horse Pass. The 112-car grain train with three locomotives derailed into the Kicking Horse River just after the Trans Canada Highway overpass. The three crew members on the lead locomotive were killed.Canadian Pacific Police Service (CPPS) investigated the fatal derailment. It later came to light that, although Creel said that the RCMP "retain jurisdiction" over the investigation, the RCMP wrote that "it never had jurisdiction because the crash happened on CP property".Transportation Safety Board (TSB) called for the RCMP to investigate as lead investigator Don Crawford said, "There is enough to suspect there"s negligence here and it needs to be investigated by the proper authority".

On 4 February 2020, the TSB demoted its lead investigator in the crash probe after his superiors decided these comments were "completely inappropriate". The TSB stated that it "does not share the view of the lead safety investigator". The CPPS say they did a thorough investigation into the actions of the crew, which is now closed and resulted in no charges, while the Alberta Federation of Labour and the Teamsters Canada Rail Conference called for an independent police probe.

On 20 November 2019, it was announced that Canadian Pacific would purchase the Central Maine and Quebec Railway from Fortress Transportation and Infrastructure Investors.Canadian American Railroad a division of Iron Road Railways. In 2002 the Montreal, Maine & Atlantic took over operations after CDAC declared bankruptcy. The Central, Maine and Quebec Railway started operations in 2014 after the MMA declared bankruptcy due to the Lac-Mégantic derailment. On this new acquisition, CP CEO Keith Creel remarked that this gives CP a true coast-to-coast network across Canada and an increased presence in New England. On June 4, 2020; Canadian Pacific bought the Central Maine and Quebec.

In March 2021, the CP offered US$29 billion to purchase the Kansas City Southern Railway, which would allow the CP to own rail lines across the entire North American continent. Kansas City Southern CEO Patrick Ottensmeyer stated that the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement signed a year earlier created a unique opportunity amid the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.Surface Transportation Board (STB) denied a voting trust between CN and KCS.

On 8 December 2021, Canadian Pacific shareholders voted to approve the railway"s proposed merger with Kansas City Southern. In the same vote shareholders also approved a special resolution to change CP"s corporate name to Canadian Pacific Kansas City Limited.

Over half of CP"s freight traffic is in grain (24% of 2016 freight revenueintermodal freight (22%), and coal (10%) and the vast majority of its profits are made in western Canada. A major shift in trade from the Atlantic to the Pacific has caused serious drops in CPR"s wheat shipments through Thunder Bay. It also ships chemicals and plastics (12% of 2016 revenue), automotive parts and assembled automobiles (6%), potash (6%), sulphur and other fertilizers (5%), forest products (5%), and various other products (11%). The busiest part of its railway network is along its main line between Calgary and Vancouver. Since 1970, coal has become a major commodity hauled by CPR. Coal is shipped in unit trains from coal mines in the mountains, most notably Sparwood, British Columbia, to terminals at Roberts Bank and North Vancouver, from where it is then shipped to Japan.

Grain is hauled by the CPR from the prairies to ports at Thunder Bay (the former cities of Fort William and Port Arthur), Quebec City and Vancouver, where it is then shipped overseas. The traditional winter export port was Saint John, New Brunswick, when ice closed the St. Lawrence River. Grain has always been a significant commodity hauled by the CPR; between 1905 and 1909, the CPR double-tracked its section of track between Fort William, Ontario (part of present-day Thunder Bay) and Winnipeg to facilitate grain shipments. For several decades this was the only long stretch of double-track mainline outside of urban areas on the CPR. Today, though the Thunder Bay-Winnipeg section is now single tracked, the CPR still has two long distance double track lines serving rural areas, including a 121-kilometre (75 mi) stretch between Kent, British Columbia, and Vancouver which follows the Fraser River into the Coast Mountains, as well as the Canadian Pacific Winchester Sub, a 160-kilometre (100 mi) stretch of double track mainline which runs from Smiths Falls, Ontario, through downtown Montreal which runs through many rural farming communities. However, CPR is in the midst of partially dismantling the stretch of double track mainline on the Winchester Sub. There are also various long stretches of double track between Golden and Kamloops, British Columbia, and portions of the original Winnipeg-Thunder Bay double track (such as 30 kilometres (20 mi) through Kenora and Keewatin, Ontario) are still double track.

The CPR also had a line of Great Lakes ships integrated into its transcontinental service. From 1885 until 1912, these ships linked Owen Sound on Georgian Bay to Fort William. Following a major fire in December 1911 that destroyed the grain elevator, operations were relocated to a new, larger port created by the CPR at Port McNicoll opening in May 1912. Five ships allowed daily service, and included the S.S. Assiniboia and S.S. Keewatin built in 1908 which remained in use until the end of service. Travellers went by train from Toronto to that Georgian Bay port, then travelled by ship to link with another train at the Lakehead. After World War II, the trains and ships carried automobiles as well as passengers. This service featured what was to become the last boat train in North America. The Steam Boat was a fast, direct connecting train between Toronto and Port McNicoll. The passenger service was discontinued at the end of season in 1965 with one ship, the Keewatin, carrying on in freight service for two more years. It later became a marine museum at Douglas, Michigan, in the United States, before returning to its original homeport of Port McNicoll, Canada in 2013.

Starting in the 1960s, however, the railway started to discontinue much of its passenger service, particularly on its branch lines. For example, passenger service ended on its line through southern British Columbia and Crowsnest Pass in January 1964, and on its Quebec Central in April 1967, and the transcontinental train Via Rail, a new federal Crown corporation that was now responsible for intercity passenger services in Canada. Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney presided over major cuts in Via Rail service on 15 January 1990. This ended service by The Canadian over CPR rails, and the train was rerouted on the former Canadian National without a change of name. Where both trains had been daily prior to the 15 January 1990 cuts, the surviving Canadian was only a three-times-weekly operation. In October 2012, The Canadian was reduced to twice-weekly for the six-month off-season period, and currently operates three-times-weekly for only six months a year. In addition to inter-city passenger services, the CPR also provided commuter rail services in Montreal. CP Rail introduced Canada"s first bi-level passenger cars here in 1970. On 1 October 1982, the Montreal Urban Community Transit Commission (STCUM) assumed responsibility for the commuter services previously provided by CP Rail. It continues under the Metropolitan Transportation Agency (AMT).

Canadian Pacific Railway currently operates two commuter services under contract. GO Transit contracts CPR to operate six return trips between Milton and central Toronto in Ontario. In Montreal, 59 daily commuter trains run on CPR lines from Lucien-L"Allier Station to Candiac, Hudson and Blainville–Saint-Jérôme on behalf of the AMT. CP no longer operates Vancouver"s West Coast Express on behalf of TransLink, a regional transit authority. Bombardier Transportation assumed control of train operations on 5 May 2014.Metra trains on the Milwaukee District/North and Milwaukee District/West Lines in Chicago, on which the CP also provides freight service via trackage rights.

The CPR ran a number of trains that transported members of the Canadian royal family when they toured the country, taking them through Canada"s scenery, forests, and small towns, and enabling people to see and greet them. Their trains were elegantly decorated; some had amenities such as a post office and barber shop. The CPR"s most notable royal train was in 1939, when the CPR and the CNR had the honour of carrying King George VI and Queen Elizabeth during their coast-to-coast-and-back tour of Canada; one company took the royal couple from Quebec City to Vancouver and the other company took them on the return journey to Halifax. This was the first tour of Canada by its reigning monarch. The steam locomotives used to pull the train included CPR 2850, a Hudson (4-6-4) built by Montreal Locomotive Works in 1938, CNR 6400, a U-4-a Northern (4-8-4) and CNR 6028 a U-1-b Mountain (4-8-2) type. They were specially painted royal blue, with the exception of CNR 6028 which was not painted, with silver trim as was the entire train. The locomotives ran 5,189 km (3,224 mi) across Canada, through 25 changes of crew, without engine failure. The King, somewhat of a railbuff, rode in the cab when possible. After the tour, King George gave the CPR permission to use the term "Royal Hudson" for the CPR locomotives and to display Royal Crowns on their running boards. This applied only to the semi-streamlined locomotives (2820–2864), not the "standard" Hudsons (2800–2819).

Between 1927 and the early 1950s, the CPR ran a school car to reach children who lived in Northern Ontario, far from schools. A teacher would travel in a specially designed car to remote areas and would stay to teach in one area for two to three days, then leave for another area. Each car had a blackboard and a few sets of chairs and desks. They also contained miniature libraries and accommodation for the teacher.

There are two Holiday Trains that cover 150 stops in Canada and the United States Northeast and Midwest.Hamilton, Ontario, Calgary, Alberta, and Cottage Grove, Minnesota, to further raise awareness for hunger issues.

The locomotive was fired up on November 13, 2020, for a steam test and moved around the Ogden campus yard. At the time, CP only had plans to utilize the locomotive for a special Holiday Train at Home broadcast,Mexico City, if the merger with Kansas City Southern Railway is approved by the Surface Transportation Board in the United States. Work on the needed overhaul began in earnest in late 2021 for a planned date in 2023.

Steamships played an important part in the history of CP from the very earliest days. During construction of the line in British Columbia even before the private CPR took over from the government contractor, ships were used to bring supplies to the construction sites. Similarly, to reach the isolated area of Superior in northern Ontario ships were used to bring in supplies to the construction work. While this work was going on there was already regular passenger service to the West. Trains operated from Toronto to Owen Sound where CPR steamships connected to Fort William where trains once again operated to reach Winnipeg. Before the CPR was completed the only way to reach the West was through the United States via St. Paul and Winnipeg. This Great Lakes steam ship service continued as an alternative route for many years and was always operated by the railway. Canadian Pacific passenger service on the lakes ended in 1965.

The Canadian Pacific Railway Coast Service (British Columbia Coast Steamships or BCCS) was established when the CPR acquired in 1901 Canadian Pacific Navigation Company (no relation) and its large fleet of ships that served 72 ports along the coast of British Columbia including on Vancouver Island. Service included the Vancouver-Victoria-Seattle Triangle Route, Gulf Islands, Powell River, as well as Vancouver-Alaska service. BCCS operated a fleet of 14 passenger ships made up of a number of Princess ships, pocket versions of the famous oceangoing Empress ships along with a freighter, three tugs and five railway car barges. Popular with tourists, the Princess ships were famous in their own right especially Princess Marguerite (II) which operated from 1949 until 1985 and was the last coastal liner in operation. The best knownVanderbilt Reef in Alaska"s Lynn Canal, constituting the largest maritime disaster in the history of the Pacific Northwest. These services continued for many years until changing conditions in the late 1950s brought about their decline and eventual demise at the end of season in 1974. Princess Marguerite was acquired by the province"s British Columbia Steamship (1975) Ltd.

To promote tourism and passenger ridership the Canadian Pacific established a series of first class hotels. These hotels became landmarks famous in their own right. They include the Algonquin in St. Andrews, Château Frontenac in Quebec, Royal York in Toronto, Minaki Lodge in Minaki Ontario, Hotel Vancouver, Empress Hotel in Victoria and the Banff Springs Hotel and Chateau Lake Louise in the Canadian Rockies. Several signature hotels were acquired from its competitor Canadian National during the 1980s, including the Jasper Park Lodge. The hotels retain their Canadian Pacific heritage, but are no longer operated by the railway. In 1998, Canadian Pacific Hotels acquired Fairmont Hotels, an American company, becoming Fairmont Hotels and Resorts, Inc.; the combined corporation operated the historic Canadian properties as well as the Fairmont"s U.S. properties until merged with Raffles Hotels and Resorts and Swissôtel in 2006.

In the CPR"s early years, it made extensive use of American-type 4-4-0 steam locomotives, and such examples of this are the No. 29. Later, considerable use was also made of the 4-6-0 type for passenger and 2-8-0 type for freight. Starting in the 20th century, the CPR bought and built hundreds of Ten-Wheeler-type 4-6-0s for passenger and freight service and similar quantities of 2-8-0s and 2-10-2s for freight. 2-10-2s were also used in passenger service on mountain routes. The CPR bought hundreds of 4-6-2 Pacifics between 1906 and 1948 with later versions being true dual-purpose passenger and fast-freight locomotives.

In 1937, the CPR acquired its first diesel-electric locomotive, a custom-built one-of-a-kind switcher numbered 7000. This locomotive was not successful and was not repeated. Production-model diesels were imported from American Locomotive Company (Alco) starting with five model S-2 yard switchers in 1943 and followed by further orders. In 1949, operations on lines in Vermont were dieselized with Alco FA1 road locomotives (eight A and four B units), five ALCO RS-2 road switchers, three Alco S-2 switchers and three EMD E8 passenger locomotives. In 1948 Montreal Locomotive Works began production of ALCO designs.

In 1949, the CPR acquired 13 Baldwin-designed locomotives from the Canadian Locomotive Company for its isolated Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway and Vancouver Island was quickly dieselized. Following that successful experiment, the CPR started to dieselize its main network. Dieselization was completed 11 years later, with its last steam locomotive running on 6 November 1960. The CPR"s first-generation locomotives were mostly made by General Motors Diesel and Montreal Locomotive Works (American Locomotive Company designs), with some made by the Canadian Locomotive Company to Baldwin and Fairbanks Morse designs.

CP was the first railway in North America to pioneer alternating current (AC) traction diesel-electric locomotives in 1984. In 1995, CP turned to GE Transportation for the first production AC traction locomotives in Canada, and now has the highest percentage of AC locomotives in service of all North American Class I railways.

Canadian Pacific Railway (28 January 2011). "Canadian Pacific trains across North America pause for day of mourning". Webcache.googleusercontent.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

McKenzie, Kenneth J. (May 1996). "Damned if you do, Damned if you don"t: An option valve to evaluating the subsidy of the CPR Mainline". Canadian Journal of Economics: 255.

8613371530291

8613371530291